Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Personifications Of History’s Ideal Citizens

Over the centuries, writers, philosophers, and politicians have created different images of the “ideal citizen.” In hindsight, not all are ideal—and a few are downright terrifying.

10 Ubermensch

The idea of the Ubermensch—variously translated as “superman,” “overman,” or even “beyond man”—has been irreversibly associated with the Third Reich and the rule of the Nazis. For the Nazis, it represented all that was good and deserving about the Aryan race and all that was degenerate and foul in other races.

It was an idea that the Nazis stole from the works of Nietzsche. It first appears in writing in his 1880s treatise Thus Spoke Zarathustra, although he’d been using the word since he was a teenager. However, he was vague about what it meant.

For Nietzsche, the Ubermensch is a complicated figure. He is capable of tyranny, but he overcomes it and works alongside others for the good of the whole. He is about equilibrium, balancing and unifying things like reason and passion and even order and chaos.

At the same time that he unites these opposing forces, he takes complete responsibility for the world around him and for his role in it. For the true Ubermensch, there would be no blaming anyone else—especially God, the Devil, the Christians, or the Jews.

The Ubermensch was also a free thinker and a citizen of the world. He could guide the development of all people on Earth. He would cast off the bonds of state and politics as an identity and embrace all. Nietzsche wrote of the Ubermensch as a goal for all of humanity, which made it appealing to the Nazis.

They also appropriated the opposite of the Ubermensch: the Untermensch. According to Nietszche, this creature was the sheeplike, ordinary citizen. But according to the Nazis, they were lower than sheep and worthy only of death.

9 The Randian Hero

Love them or hate them, the works of Ayn Rand make a definite statement about success, industry, and the human condition. Many of the heroes (or antiheroes) of her works conform to a standard that is aptly named the Randian hero.

These heroes lack the characteristics of the American ideal: the selflessness, the sacrifice, the inherent goodness. Instead, they are the ideal tycoon, the magnates of might and industry who sit at the top of their organizations and on mountains of money. They are only out for themselves.

Rand wrote that a man’s first duty is to himself. For the idealized version of man, that is his only duty. Greed is the opposite of sin. You can never have too much wealth, and nothing bad can come of doing whatever it takes to maximize your profit and prosperity. Become a greedy capitalist, the Randian hero declares, and you’ll have happiness with no pain.

8 The Knight Of Faith And The Knight Of Resignation

Soren Kierkegaard defined a key difference in how we look at the world in his knight of infinite resignation and his knight of faith. He tells the story of Agamemnon and Abraham, two men who are asked to sacrifice their children.

Agamemnon is forced to choose between his daughter and his people, ultimately sacrificing Iphigenia to bring back the winds and allow his people to reach the battlefield that will become Troy. That makes him the knight of infinite resignation. Faced with the betrayal of his people or the sacrifice of his daughter, he chooses the greater good and is completely resigned to the part he needs to play in life.

Things work out differently for Abraham. God tells Abraham to sacrifice Isaac, his only son. Although he faces a situation as horrible as Agamemnon’s, Abraham has something that his Greek counterpart doesn’t: faith. When Abraham takes Isaac to the mountain, he does so willingly, without the resignation of Agamemnon. Ultimately, the sacrifice is averted.

Kierkegaard defines the two figures as the extremes of bravery. While the knight of faith invests all into an end goal and an outside, unknowable figure, the knight of infinite resignation is brave in taking the weight of the world on his shoulders alone.

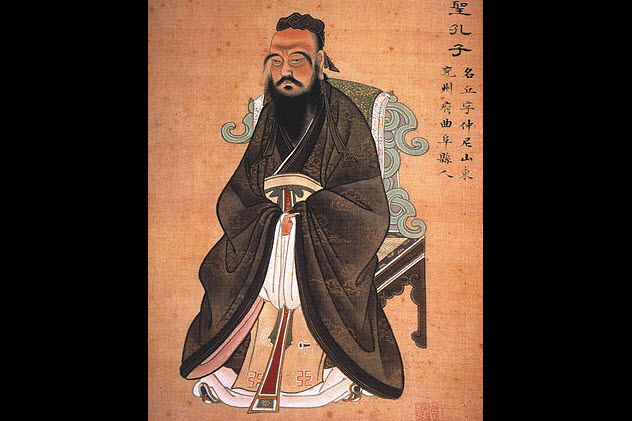

7 Junzi

According to Confucius and Chinese philosophy, the junzi is the ideal person. More precisely, the junzi is as close to an ideal person as most people can hope to get. He’s more than just a superior man; he’s a virtuous one.

The highest level that can be achieved is the shegren (sage). Rising to this state is akin to becoming a saint. As that’s out of reach for most of us, the next best thing is the junzi. At the time that Confucius was teaching, the term actually referred to the son of a lord or a prince. After Confucius, junzi became more broadly applied to anyone who was striving to be a better person.

However, this ideal also refers to a person’s relationships with the state, the community, and everyone else around him. The junzi (as opposed to his polar opposite, the xiaoren) must embody the five virtues of Confucian philosophy: benevolence (ren), knowledge (zhi), trustworthiness (xin), righteousness (yi), and ritual propriety (li).

In a nutshell, it’s a mastery of all the proper ways of going about your business, whether it’s how you treat members of different classes, honor your ancestors, or conduct yourself when drinking. It’s knowing your responsibilities and acting in accordance with your station.

6 The New Soviet Man

In 1917, the idea of the New Soviet Man was established as a template for the masses to strive to achieve. It was the embodiment of communism and a clear message as to how people in the Soviet Union should fulfill their roles in society.

The idea was partially based on Nietzsche’s Ubermensch and evolved as the regime changed hands and communist ideas grew. Marx’s models in The Communist Manifesto were distinctly based on economics. According to Lenin, the only way that the communists would be able to create the utopian world that they envisioned was to cast off previous social constraints and transform the population into the New Soviet Man.

The New Soviet Man possessed infinite energy and mastered his own feelings so that he was no longer driven by raw emotion. Trotsky called this master of emotion a “higher biological type.” He opposed anyone who refused to conform to the new standards of the communist government. Those people were abominations and failures, lesser beings in the same way that the New Soviet Man was superior.

However, this idea fell out of favor. Even as members of the working class were elevated into government positions to establish their unfailing loyalty, they were becoming angry about eugenics programs to create the genetically superior New Soviet Man.

By the 1920s, the New Soviet Man was taken in another direction by Stalin. His focus was on industry and creating an ideal man who labored inside the symbol of Soviet superiority: the factory. The Soviet Union was a machine, and it was only with the labor of its ideal pieces that true utopia could be achieved.

5 The Political Soldier

When Britain’s National Front was taken over by extreme right-wing members, the idea of the Political Soldier became popular with a certain segment of the population. In 1984, Derek Holland outlined his ideas in a pamphlet of the same name.

He called for the creation of an elite warrior class who held their religious and spiritual beliefs above all else. Ideally, they would fight and die for their cause and their ideas. Likening them to the Roman centurions and the knights of the Crusades, he said that the only thing that would stop these warriors was death.

Holland fought against the alliance between communism and capitalism, which he saw as interfering with the everyday labors of ordinary countrymen. He advocated support for Libya and Palestine. He also wanted a mass expulsion of Zionist Jews and media influence from what he deemed the “enslaved nations.” At the forefront of this fight was the Political Soldier.

The Political Soldier was also known as the Warrior Saint, the herald of a new world order, the “Good and the True, the Pure and the Admirable.” In 1994, Holland updated the pamphlet, calling again for a holy war and defining the men needed by the world. They were highly disciplined men devoted to a single cause. They would die in pursuit of their ideal, even if it meant driving a bomb into the enemy.

According to Holland, whole battalions of them were needed to oppose the forces of the capitalists, the Freemasons, the communists, and the Zionists.

4 Mussolini’s Fascist New Man

With the rise of Benito Mussolini came the desire for the development of the New Man, an ideal that would elevate the fascist regime to its rightful place. Highly disciplined, these men would be created through a series of drills and exercises and then become hardened in combat.

The fascist New Man also had a physical form. In fact, Mussolini’s central stadium was surrounded by figures of nude athletes who had come from every Italian province as a show of unity in striving toward the ideal. These men would do more than just fight in battle. They would also return with the most important element of the fascist New Man: the willingness to do whatever was necessary to give Italy back its soul.

The fascist New Man was a study in contrasts: contemplative and daring, authoritative and loved by the people, realistic and imaginative, especially of future possibilities.

Military virtues drove the creation of the fascist New Man, who embodied the values of ancient Greece and Rome. Mussolini saw himself as the man to create this new Italy of ideal citizens, working with the masses as though they were unformed clay or blank paper that was waiting for someone to make their mark.

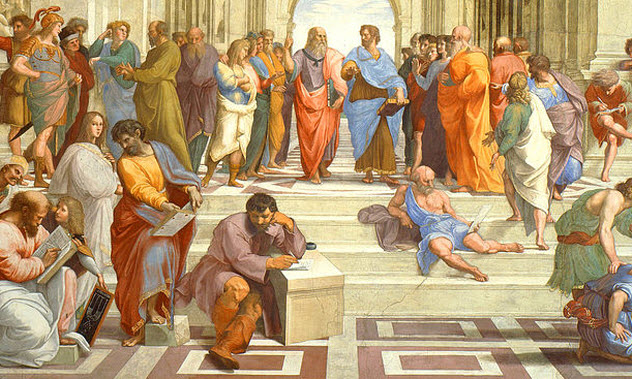

3 The Philosopher King

The Republic by Plato tackles an age-old question: What makes a good leader?

Through his narrator, Socrates, Plato says that the ideal leader is the philosopher king who has all the tools needed to rule a city best. The philosopher king can see the truth for what it is and apply practical knowledge to any situation. He welcomes learning and hates falsehoods.

Plato admits that plenty of bad philosophers exist. He believes that most of them have been corrupted by education and their surroundings. With a proper education, he says, philosophers can go on to become teachers as well as leaders.

Plato believes that these guardians should be taught poetry, music, math, astronomy, harmonics, and physical education. They should also study the dialectic, which will teach them how to embrace the Form of the Good, a knowledge that continuously grows and enlightens all whom it touches. After that, a person would need 15 years of political training before assuming a leadership position in his city.

Plato says that the main problem for the philosopher king is the people’s hostility toward him. As a result, the philosopher king performs best when placed in charge of a new city, building it from the ground up and teaching all the subjects to appreciate knowledge and the Form of the Good.

2 The Utopian Socialist New Man

The journey of the New Man in socialism is a strange one. In the 1950s, China reorganized their society based on a communal ideal. Everyone was working together to do everything, theoretically creating the building blocks of a new society. Men and women raised under a socialist regime who had completely converted to this new way of life would become the socialist New Man—all working for the greater good.

Charles Fourier had a slightly different idea of utopian socialism. He believed that the biggest hurdle for socialist success was a rebellion against the monotony. So he proposed communities made of work units called phalanxes, where workers would rotate jobs with a military precision in which people would thrive. According to Fourier, the workers would be happier and more productive, and the community would be infinitely more successful.

Fourier believed that the New Man of his communities would thrive well beyond what most thought possible. Both men and women would reach heights of at least 215 centimeters (7 ft), and the average life span would grow to 144 years. These people would be highly resistant to pain and able to regrow teeth. After only 16 generations in the Utopia he called Harmony, his new Harmonian men and women would develop something else: a tail.

This wasn’t a boring tail, either. With 144 vertebrae, the tail would help people to swim like fish and climb trees like they were born there. Most impressively, these people would be able to play musical instruments by using the little hand that would grow on the end of their tails.

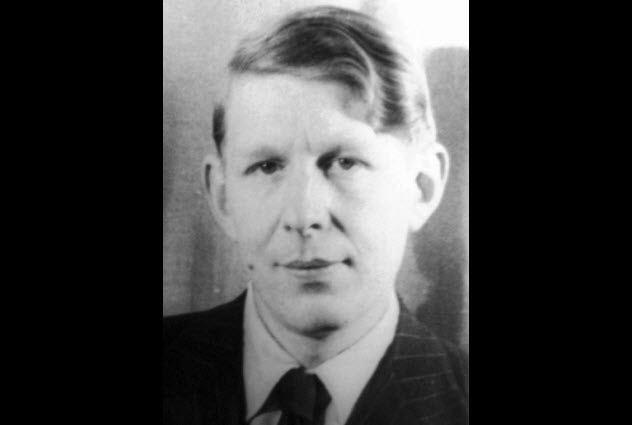

1 The Unknown Citizen

Pulitzer Prize–winning poet W.H. Auden wrote the satirical work “The Unknown Citizen” in 1940. The poem profiles the ideal citizen JS/07 M 378 in a piece etched into a monument erected by an unnamed state. It’s devastatingly dark and poignantly beautiful as Auden highlights what the State truly believes is the ideal man, and department after department tells of how he excelled.

The Bureau of Statistics never recorded a complaint against him. For most of his life, he worked, doing what he was told and performing satisfactorily. He liked a drink and had some friends. He read the paper and looked at the advertisements. Although he went to the hospital once, he was insured and recovered well.

He bought all the modern comforts and necessities but didn’t spend too much. He supported peace during peacetime and war during times of conflict. JS/07 M 378 always agreed with popular opinion. He married, had the right number of kids, and embodied the spirit of the ideal everyman.

As the poem notes, all this made him happy and free, or someone would have heard about it. This suggests that the ideal citizen isn’t the one who changes the world but the one who is a nameless, faceless cog in the gears of society.