Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

10 Rarely Told Tales Of Columbus, History’s Greatest Explorer

It’s generally accepted that Christopher Columbus has been taking credit for a “discovery” that he didn’t really make, but that hasn’t stopped the celebration of Columbus Day. Schoolchildren of all ages are lauded with the myth-as-history tales of Columbus’s supposed “discovery” of the New World, but there are some other stories that they should probably be taught instead.

SEE ALSO: 10 WTF Facts That Prove Columbus Shouldn’t Have His Own Holiday

10 The Mysterious Green Glow

On October 11, 1492, Columbus recorded something strange in his journals, and we’re not talking about his tendency to refer to himself in the third person, which takes a special sort of personality. Columbus noted an odd phenomenon so faint or so far away that only one other person had been able to see it when he pointed it out from the deck of the Santa Maria. Something was glowing, which Columbus thought may or may not be land. The glow was irregular and incredibly faint, and it seemed to be moving.

There have been plenty of guesses as to what it was that Columbus saw and was so captivated by that he thought it important enough to record it. Explanations included candlelight or firelight on distant land, canoes rowing on the nighttime ocean, or the explorers’ eyes simply playing tricks on them. A few centuries later, a naturalist suggested what looks like the most likely answer—luminous worms.

Only recently have biologists begun to unlock the secrets of the species that might be responsible for the mysterious glow that Columbus spotted off the deck of his ship. The aptly named fireworms are little more than 1 centimeter (0.4 in) long and live in coastal waters, where Columbus would have been sailing. During their mating cycle, the worms swim close to the surface, and the green glow of the females attracts the males as they perform their circular dance. The display only lasts for about half an hour before the worms retreat to the safety of the ocean floor, but it’s entirely possible that Columbus’s mysterious light was the age-old dance of fireworms.

9 The Jewish Theories

Considering how famous (or infamous) he is, there’s a lot that we don’t know about Columbus’s personal life and childhood. According to some historians, it’s looking more and more like he was secretly Jewish, and contrary to popular belief, he wasn’t from Italy at all. While it’s just a theory based largely around a rather scattered set of clues, it just might carry some weight.

It started with a linguistic investigation by Georgetown University linguist Estelle Irizarry. When she reviewed dozens of Columbus’s personal letters, she found some signs that his first language might have been Catalan. Those included the use of a particular punctuation mark called the virgule, a slash used to show where the pauses come in his writing, a mark specific to those who come only from Catalan-speaking areas of the Iberian Peninsula. She also found a few telling signs in some of his personal letters, which were never meant for anyone outside his family to see. In correspondence between Columbus and his son, she found the Hebrew letters bet-hei, a blessing found in the letters of practicing Jews. (The mark was left off of letters that were addressed to both family and crown.) His will also contained some things that seemed telling, like the traditional Jewish practice of setting aside some of his estate to go to poor girls who otherwise would have no dowry.

Irizarry also feels that Columbus tried to hide his Catalan Jewish background by telling people that he was from Genoa. Historians have never been able to definitively pin down Columbus’s birthplace. Although it’s generally said to be Genoa, others have also suggested Corsica, Portugal, or even Greece. The idea that he was actually from Spain—and a practicing Jew—might cast his voyages in a whole new light.

In 1492, Spain was going through a major ethnic cleansing. In March, around 800,000 Spanish Jews were given an ultimatum: Convert or get out. The date of the ultimatum? August 3, 1492. Perhaps coincidentally, this is the date that Columbus and his crew set sail.

If Columbus really was a Catalan-speaking Spanish Jew, some think that he might have had other motives for setting out to the New World. He may have been looking for a new Jewish homeland, or he may hoped to claim riches to help reestablish their home in Jerusalem. It’s just a theory, certainly, but it seems clear that there was more going on than we’re likely to ever know.

8 Texas Longhorn Cattle

Texas Longhorns—they’re one of the most distinctive types of cattle in the United States. They’re a huge part of Texas’s state identity, and when the University of Texas at Austin took a crack at decoding the genome to find out just what went into making the famous Texas Longhorn, they found something unexpected. They’re descended from cattle that made the trip across the ocean with Columbus.

They looked at more than 50,000 genetic markers and traced most of the cattle’s ancestry to the taurine variety of cattle, which come from the ancient aurochs that once roamed the Middle East around 10,000 years ago. A smaller part of the genome (about 15 percent) came from the indicine aurochs of India, and that’s the part that gives some of them their hump. The indicine cattle spread from India, through Africa, and up into the Iberian Peninsula, where they influenced cattle genetics there.

To find out just how cattle from the Iberian Peninsula made it to the New World, they looked at the earliest voyages across the ocean. The first cattle brought to the New World (on Columbus’s second voyage) ended up in the Caribbean. Records of how many were on the ship are long gone, but it’s estimated that he would have had somewhere between 20 and 30. Those first cattle were likely pregnant females that were picked up on the Canary Islands. Gradually, the descendants of those first few spread to the mainland with the spreading European population. They turned feral and adapted to life in the desert, which they were already well-equipped to survive thanks to their Indian and African ancestors.

7 The First Tax In The New World

“No taxation without representation” has been the rallying cry of the young US since the middle of the 18th century, but taxes were problematic long before then, and they were introduced to the native population by Columbus.

On his second trip to the New World, he settled the ill-fated colony of La Isabela with the goal of trading with the indigenous population. He’d already met and “claimed” the native Taino, a well-established, thriving society that would be nearly extinct by 1550. La Isabela was to be a purely economical settlement, but in order to turn a profit, Columbus needed guaranteed income in the form of gold. In 1495, he enacted what’s known as the first instance of taxation in the New World, a tax that the Taino couldn’t pay.

The tax was due every three months, and it was to be paid for every man in the settlement over the age of 14. They were a few options for payment. The first was described as one hawk’s bell of gold, which wasn’t achievable for a people who hadn’t placed any particular value on gold. They hadn’t developed their mining and smelting operations to the point where they could keep up with that kind of demand. Alternately, Columbus allowed them to pay off their debt with 11 kilograms (25 lb) of cotton or with manual labor.

The ability to pay in physical labor instead of gold made the colony different than other factorias that had been set up by the Spanish, and it also hastened La Isabela’s downfall. Gold wasn’t plentiful enough to allow the workers to pay their tax with it, and when the funds began to dwindle, the whole structure began to crumble.

6 The Wolof Slave Rebellion

The Columbus family was at the heart of another infamous first in the New World—the first organized uprising of slaves.

It happened in what is now the Dominican Republic, and it was led by the Wolof men from Senegal. They had been taken to the New World about two decades before the Christmas 1522 uprising. They were captured during a series of wars that ravaged the area known as Senegambia. Those prisoners eventually ended up in Portugal and Europe. From there, they were shipped off to the New World.

On December 25, a group of around 20 men armed themselves with machetes that they had been given to cut sugar cane and became a rather effective fighting unit. They were so effective, in fact, that they held out for several days. (It helped that they chose Christmas to revolt, knowing that their overseers would be drunk after a Christmas Eve celebration.) They also held their own against the initial Spanish cavalry charges.

They headed for an estate on the Zuazo plantation, where they planned to execute those in charge and free the roughly 120 slaves who were kept there. Once the Spanish got word of what was going on and where the Wolof seemed to be headed, however, they organized a better resistance and put down the rebellion, but not before they’d lost more than a dozen men total.

The whole thing happened on the holdings of Diego Columbus, Christopher’s son and the appointed viceroy of the Indies. The rebellion kicked off only a few miles from his own estate, and the resultant legislation was bizarre, to say the least. In response to the rebellion, Spain outlawed the use and introduction of so-called gelofes into a slave population. That included anyone raised by Moors or anyone from Guinea, as they were deemed too dangerous to be good workers on Spanish holdings.

5 La Isabela And The Silver Ore

La Isabela was founded by Columbus after he returned to Spain full of stories of the fortune and glory they were going to find there—if only he had a little more time, money, and people. When he settled there in 1494 with about 1,500 people, it would take only about four years for the colony to be completely abandoned. There was no gold or silver, but there was plenty of starvation, disease, and death, so much so that Columbus himself headed back to Spain in 1496.

We’ve always known that the settlement was a failure, so archaeologists probably weren’t expecting to find gold and silver when they excavated La Isabela, but that’s exactly what they found. Excavations turned up samples of galena, an ore that contains silver. They also found lead silicate, a by-product of the smelting process that’s usually used to extract the silver, seeming to indicate that there was a smelting operation going on there.

Silver deposits were never recorded as having been found in the area around La Isabela, so the evidence seemed to completely contradict what we’ve always known about the settlement, until they started looking at the makeup of the mineral itself, with the help of an archaeometallurgist from the University of Arizona. Then, they were able to identify the galena as having come from Europe. Tracing Columbus’s journey showed that he’d stopped at several places where galena occurred along the way. A few more experts weighed in, and they realized that it was a standard process for gold- and silver-seeking operations to bring along a sample of rock that they knew contained what they were looking for. These samples had been smelted, however, perhaps in an desperate attempt to make what little money they had last a bit longer.

4 He Devastated Europe With Disease

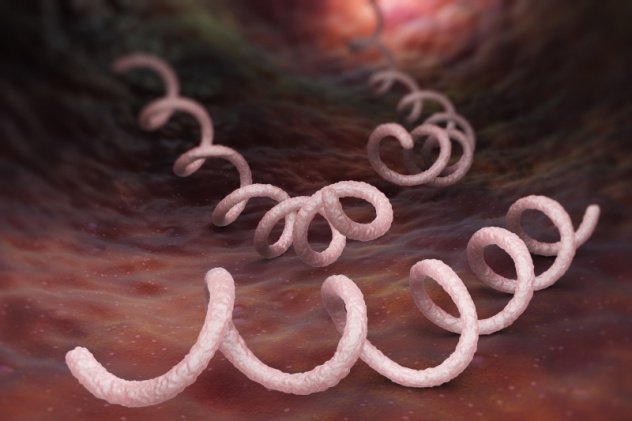

We all know about how the native populations in the New World suffered and died from the introduction of all sorts of new European diseases after encountering Columbus and his men. Less talked about is the disease that Columbus and company brought back to Europe with them—syphilis.

It’s no coincidence that the first confirmed case of syphilis happened in Italy in 1495. When it started to spread, it was horrific enough that some friars thought the outbreaks were signs heralding the Second Coming. The church itself cracked down on the afflicted. Much like with those who contracted leprosy, syphilis was thought to be a very visual sign that someone was doing something that they weren’t supposed to.

Even archaeological evidence dates the arrival of syphilis in Europe as coinciding with Columbus’s return from the New World. Older skeletons once thought to be the remains of syphilis sufferers have tested negative for the virus. Before you start blaming long months at sea with no women in sight for the spread of the disease, you should know that it probably didn’t happen that way at all.

We’ve always known that syphilis is sexually transmitted, but tracing the earliest strains back to the New World has shown that it likely didn’t start as such. In its New World form, it was called yaws, and it started with red patches on the skin and escalated into something permanently disfiguring. When it was taken from the wet, humid New World to the colder European climate, it mutated not only to survive in a different environment, but to be transmitted by sexual rather than causal contact.

3 The Most Accurate Portrait We Have

There are a lot of famous portraits of Christopher Columbus, so many that it’s easy to forget that we don’t actually know what he looked like. There are no surviving portraits of him that were painted during his lifetime, and for a long time, people have been trying to figure out what he looked like.

The best written description we have of him comes from his son, Fernando. Fernando describes his father as “a vigorous man, of tall stature, with blond beard and hair, clear complexion and blue eyes,” which is nothing like some of the usual depictions of him. Because Columbus was never accurately represented in his lifetime as well as his rather mythic status as a larger-than-life figure, it’s also likely that even many of the earliest portraits of him were a bit more embellished and stylized than usual. There are, however, a couple portraits out there that are probably more accurate, and one is the piece done by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio.

The other is part of a larger piece done as a triptych and altar piece called The Virgin of the Navigators. In the work, the Virgin Mary stands watch over a group of explorers, including a robed, late-middle-aged Columbus (shown above). Unlike many of the portraits that claim to show him, his appearance in The Virgin matches all of the contemporary reports of what Columbus would have looked like. Most importantly, the artist, Alejo Fernandez, was of the right age and in the right place to at least have seen him.

Fernandez was born about 30 years before Columbus died, and as he was working in Seville, he would have known—and probably consulted with—others who had known Columbus in life. Art historians also point to a period of Spanish pride, making the image of Columbus not only likely to be accurate, but finely dressed in an attempt to create him as not just as an explorer, but as an icon of the country that he represented. Also weighing in on the side of the portrait being accurate is the idea that it was created with the intention for the figures (which also include Martin Alonso Pinzon, Hernan Cortes, and Amerigo Vespucci) would be instantly recognizable to the viewers who’d lived at the same time as the explorers.

2 The Most Devastating Disease

La Isabela had a whole bunch of problems, and for a long time, it was thought that diseases like smallpox, tuberculosis, and influenza were largely to blame for the deaths that occurred when Columbus and his crew settled in what became Europe’s first permanent (albeit short-lived) settlement in the New World. When archaeologists took a closer look at some of the skeletons that were excavated from the colony, they found something rather unexpected. One of the biggest problems that the settlers faced was something usually associated with long months at sea—scurvy.

Scurvy was well-known by the 1700s (unlike the 1490s), and it would kill more sailors than shipwrecks would. It happens when there’s a complete vitamin C deficiency, and symptoms are varied. They can include headaches, bleeding gums, reopening of healed or partially healed wounds, joint pain, rashes, or even mood swings and exhaustion. The symptoms of scurvy can take up to three months to manifest, so it was likely that by the time the settlers were a month or so into their foray into the New World, they were starting to feel the ill effects of what had started during the ship’s crossing.

It’s also something that could have been prevented, and some of the skeletons showed signs that some people had started to repair the damage done to their bodies by reintroducing some vitamin C. It was, after all, all over the place. The scurvy-ridden explorers had landed in a place rich with native fruits and vegetables, and that might have saved their colony. They were surrounded by cherries, guavas, yuccas, sweet potatoes, and so on. According to modern doctors, the daily amount of vitamin C that it takes to keep scurvy at bay can be attained from a few ketchup packets. Unfortunately, the European settlers seemed more interested in finding gold than exploring the local cuisine, and they also relied heavily on the supplies and stores that they brought with them rather than procuring new food sources. Doing so might have saved lives.

1 What Happened To The Santa Maria And The Villa De La Navidad?

It starts like all good stories do—with a party and someone left in charge who probably shouldn’t have been. In December 1492, Columbus and his crew were off the coast of Haiti. After what we can only image was a pretty rowdy Christmas Eve party, the crew all fell asleep, and steering the ship fell to one of the only people still sober—the cabin boy. He was, understandably, ill-equipped to navigate the waters by himself, and the Santa Maria was wrecked on a coral reef. Christmas Day was spent salvaging what they could, including stripping timbers from part of the ship itself. Those timbers were then used to make a fort that was christened Villa de la Navidad.

When Columbus returned on his next trip, the fort was gone, along with the remains of the Santa Maria. Today, people are still looking for both. At the head of the search for the location of La Navidad is amateur archaeologist Clark Moore. We’re using the term “amateur” only as a technicality; Moore is credited with finding more than 980 significant sites in Haiti, where he spends winters exploring the lands that Columbus settled. He’s pretty sure that he has a good idea where La Navidad was built—on a hill amid villagers who ultimately burned it to the ground when they realized the character of those who settled there.

And as for the Santa Maria? In 2014, it was claimed that marine archaeologists led by Barry Clifford had found the wreck by closely studying contemporary accounts of the trip and then diving in the right spot. Unfortunately, UNESCO stepped in with the final word, saying the wreck found wasn’t of the Santa Maria. Their conclusions were based on finding fasteners and the remains of copper fittings. Those, along with evident shipbuilding techniques, dated the wreck to sometime in the 18th century.

That last fact only helps us to conclude that in spite of being known throughout Europe and the Americas as one of the great explorers of the Age of Exploration, there’s more myth and mystery about Christopher Columbus than there is historic fact.