History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

10 Audacious Historical Heists Fit For Hollywood

As Hollywood knows, a well-executed heist always makes for good entertainment. We enjoy seeing an intricate plan masterminded by a criminal genius play out to perfection. At the same time, we also like the less subtle, more violent approach with guns, masks, and explosives galore. However, Hollywood tends to stage all its heists in modern settings even though the daring robbery is not a new phenomenon.

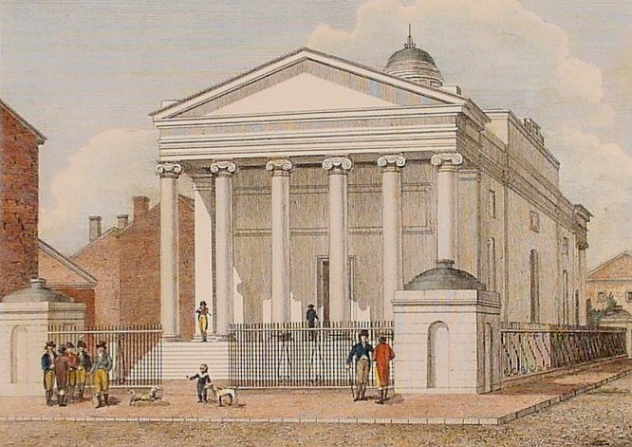

10 Bank Of Pennsylvania Heist

1798

The Bank of Pennsylvania Heist is usually billed as America’s first bank robbery. It occurred in late August 1798 at the Bank of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. Today, it’s better remembered for the false imprisonment of Pat Lyon, who later successfully sued for damages.

The robbers got away with over $162,000. That impressive number limited the suspect pool to people with the required skills or access to pull it off. Blacksmith Patrick Lyon became the primary suspect, as he’d recently installed new locks on the vault doors of the bank. Authorities and bank officials believed that he forged another key for himself and simply walked inside the vault while the bank was empty. Based on their suspicions, they arrested Lyon and set his bail at $150,000.

The real culprits turned out to be two men named Thomas Cunningham and Isaac Davis. Cunningham, a porter at the bank, served as the inside man. He died of yellow fever soon after the heist. Davis was caught after depositing stolen money at banks around Philadelphia, including the one he’d robbed. However, he later received a pardon in exchange for giving back the money and making a full confession.

As for Lyon, he wrote a book about his experience and sued for wrongful imprisonment afterward. Some of the country’s top lawyers got involved, and it was one of the first trial in the US to deal with the concept of probable cause. Lyon received $9,000 in damages.

9 Eastcastle Street Robbery

1952

Back in 1952, a group of seven masked thieves robbed a post office van making its rounds through central London. The criminals used two cars to sandwich and trap the van. After taking out the driver and guards, the robbers drove off with the van. It was later found abandoned near Regents Park after the culprits stole 18 mailbags. In total, the thieves made off with £287,000, courtesy of the Royal Mail.

At that point, the Eastcastle Street Robbery was the largest theft in postwar Britain. It was also the first in a long line of daring heists perpetrated by London’s criminal underground, including the infamous Great Train Robbery and the more recent Hatton Garden Heist. Prime Minister Winston Churchill became personally involved and received daily updates on the status of the investigation. Over 1,000 police officers joined the search, and a £25,000 reward was offered for information leading to the recovery of the money or the arrest of the perpetrators.

Today, we know that the heist was organized by notorious London mobster Billy Hill. The other robbers included the usual suspects of London’s crime scene, such as Terry “Lucky Tel” Hogan and George “Taters” Chatham. Despite the huge manhunt, no one was ever convicted of the crime.

8 Ioanid Gang Robbery

1959

Separating truth from propaganda in a Communist regime can prove difficult. According to the official version, in 1959, a gang of Jewish Romanian intellectuals pulled off the biggest heist in Communist history.

The robbers became known as the Ioanid gang, named after two of its members, Alexandru and Paul Ioanid. They were members of the Romanian Communist Party, and they managed to relieve the state bank of 1.6 million lei. The criminals wore masks and were armed with semiautomatic machine guns. They robbed the driver of an armored van at gunpoint. Civilians witnessed the whole thing going down, but they cheered the robbers on for a simple reason—they thought it was a movie. All it took was a simple “film in progress” sign to convince onlookers that the robbers were actually actors filming a scene.

Despite their successful getaway, the secret police managed to arrest all six perpetrators within two months. They were then given quick trials behind closed doors and sentenced to death. Monica Sevianu, the only woman of the group, was given a life sentence because she was a mother.

Before their executions, members of the gang were forced to act out their heist in a propaganda film titled Reconstruction. The film was intended only for members of the Communist Party. Since it’s the only official record that exists today, it’s hard to say how much of it is true.

7 Helsinki Bank Robbery

1906

During the early 20th century, the Bolsheviks came to power after the Russian Revolution and founded the Soviet Union. At the start of the century, though, they were still an emerging faction and needed funds in order to grow. On several occasions, the Bolsheviks obtained those funds by staging bank robberies.

In 1906, Finland was a Grand Duchy and part of the Russian Empire. Therefore, it had plenty of rubles and many Bolsheviks to steal them. The man behind the heist was Nikolay Burenin, concert pianist and composer by day, Bolshevik revolutionary by night. By 1906, Burenin was already involved in smuggling people and manufacturing explosives, using his home on the border between Russia and Finland as a base for Bolshevik operations.

On February 26, Burenin organized the robbery of the Russian State Bank in Helsinki. Members of the Latvian Social Democratic Workers’ Party, 15 in total, stormed the bank, killed a guard, and made off with over 170,000 rubles.

The Latvian revolutionaries believed that a victory for the Bolsheviks meant a free Latvia and were favored by Lenin for such jobs due to their determination and penchant for violence. Even though several robbers were killed or captured along the way, the leader reached Burenin, who was in Tampere giving a concert, and turned over the money. Afterward, Burenin left the country with Soviet writer Maxim Gorky, who was posing as his personal secretary.

6 Northfield Bank Robbery

1876

The Wild West was filled with larger-than-life characters, and few were grander than Jesse James. History has been awfully kind to him, and James has often been (incorrectly) portrayed as the Robin Hood of the West instead of the robber and murderer that he was. James committed most of his dastardly deeds alongside his brother, Frank, as part of the James-Younger Gang. Consisting mostly of former Bushwhackers, the gang was made up of the two James brothers, four Younger brothers, and various other associates during its roughly 10-year lifespan.

The James-Younger Gang met a violent end when it attempted to rob the First National Bank of Northfield in Minnesota. On September 7, 1876, eight members of the gang rode into town and attempted a daring daylight robbery. Three of them went inside the bank while the remaining five stood guard outside. After a few minutes, people realized that the bank was being robbed and sounded the alarm. After a quick shoot-out, four people were dead—the bank clerk, two gang members, and a Swedish passerby.

The remaining outlaws made it out of town with a posse hot on their heels. Frank and Jesse James split from the rest and managed to evade the lawmen, who kept chasing the others. After a few weeks, the posse caught up to the Younger brothers, and all remaining members were either killed or captured. The event is now celebrated annually in Northfield during its “Defeat of Jesse James Days.”

5 Bank Of Australia Robbery

1828

In the early 19th century, Australian states served as penal colonies for British criminals. In New South Wales alone, there were around 165,000 convicts. There were also plenty of former convicts who’d finished their sentences but chose to stay put.

One such man was Thomas Turner, regarded as the finest stonemason in Sydney. When it came time to build a stone vault for the city’s new bank, Turner was the man to call. However, bank officials didn’t know that Turner also built a sewage drain passing right underneath the vault and exiting at Sydney Cove. Turner saw a golden opportunity, so he started planning what would become the biggest bank robbery in Australia’s history.

In 1828, Turner enlisted two Irishmen, James Dingle and George Farrell, to carry out his plan. They also recruited a blacksmith named William Blackstone. The three of them spent their Saturdays digging to reach the vault. While Dingle was a free man, Farrell and Blackstone were working convicts, and Saturday was their only day off. Eventually, Dingle recruited two more men to speed up the process.

Turner’s plan worked. The robbers dug their way into the vault and left with £14,000. However, they had to do it on a Sunday, when the bank was closed. This meant bribing the muster clerk to let Blackstone and Farrell have the day off. Eventually, the clerk made the connection, and the men were brought in for questioning.

The men were dismissed and might have gotten away for good if it weren’t for greed. Dingle and another man involved, Thomas Woodward, conned Blackstone out of his share. In 1831, Blackstone was arrested on an unrelated charge. In exchange for a pardon, a reward, and a chance at revenge, he gave up the other robbers. The money was never recovered.

4 Kakori Conspiracy

1925

In 1947, the British Crown ended its rule in India, and the subcontinent was split into several sovereign states. Long before that, however, there were many organizations fighting for Indian freedom. One of those organizations was the Hindustan Republican Association (HRA). Throughout the early 20th century, they engaged in many activities to minimize the authority of the British Raj. Most memorable was a train robbery in 1925, now known as the Kakori Conspiracy.

On August 9, 1925, 10 revolutionaries, led by Ashfaqullah Khan and Ram Prasad Bismil, boarded the train from Shahjahanpur to Lucknow. The train was carrying money destined for the government treasury. Near the village of Kakori, the robbers stopped the train and held up the British guards. They made off with 8,000 rupees but also accidentally shot a passenger during a scuffle.

Word of the robbery spread fast, and the British government feared the effect it might have on the population. An extensive manhunt began. Over the coming months, 40 people were arrested in connection with the train heist and the HRA. Four men were given death sentences and another life in prison, while everyone else received up to 14 years in prison.

The severity of the sentences caused exactly what the government wanted to avoid—public outcry in favor of the revolutionaries. A committee headed by Motilal Nehru, patriarch of the prominent Nehru-Gandhi political family, was formed to defend the convicts. Their efforts were mostly in vain. Apart from a few dismissed minor convictions, all other sentences were carried out.

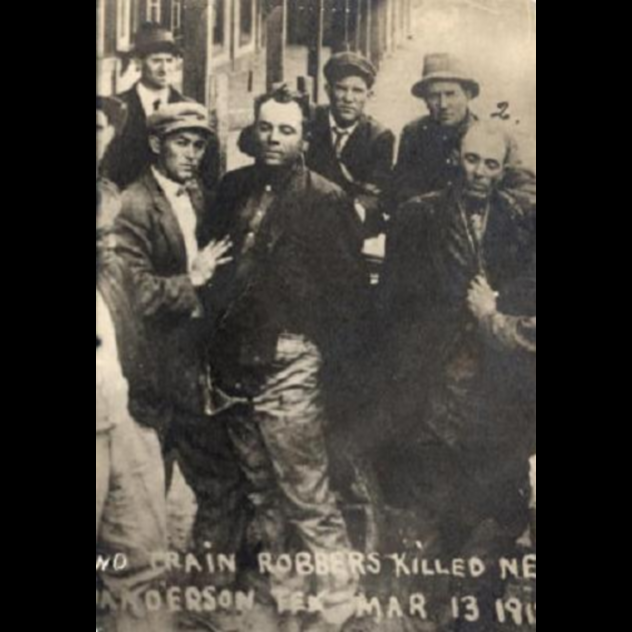

3 Baxter’s Curve Train Robbery

1912

Another one of the Wild West’s most infamous icons is Butch Cassidy. Throughout most of his career, Cassidy was surrounded by an eclectic group of criminals known as the Wild Bunch. The gang dissipated in 1901, when the members split up in an effort to evade the Pinkertons. Most of them met a violent end in shoot-outs with the law.

One member who survived was Ben Kilpatrick, aka “the Tall Texan.” He was arrested in 1901 and sentenced to 15 years in prison. After serving 10 years, he was released and quickly returned to a life of crime with a new partner named Ole Hobek.

Despite a few successful robberies, this partnership ended on March 13, 1912. Kilpatrick and Hobek were on the Southern Pacific Number Nine Train from Dryden to Sanderson, Texas. At Baxter’s Curve, the robbers put on masks and held up the train’s four crewmen. While Hobek stayed with the engineer in the locomotive, Kilpatrick took the other three to disconnect the passenger cars. On the way, one of the crewmen, David Trousdale, managed to secretly arm himself with an ice mallet. When the opportune moment came, he struck the Tall Texan in the head and killed him. Now armed with Kilpatrick’s gun, Trousdale waited for Hobek to check in on them and shot him in the head. Men are shown above posing with their bodies (Kilpatrick is on the left.)

Trousdale was hailed a hero and rewarded for his bravery. Meanwhile, the Baxter’s Curve train robbery became romanticized as the “last train robbery in Texas,” although that’s not strictly accurate.

2 Tiflis Bank Robbery

1907

When Georgia was part of the Russian Empire, the modern capital of Tbilisi was called Tiflis. Bolstered by their success in Helsinki, the Bolsheviks saw Tiflis as a prime target for another “funding campaign.” The decision was made to rob a stagecoach delivering money to the state bank in Tiflis. What made this robbery stand out was the fact that it was masterminded by a young Bolshevik poet called “Koba,” whose real name was Joseph Stalin.

Stalin reached out to an old school friend who was working as an accountant for the bank. He found out that on June 26, 1907, the bank would be receiving a delivery of one million rubles. The plan was to ambush the stagecoach and take the guards by surprise.

Although Stalin was the planner, the robbery was carried out by another Bolshevik named Kamo. On the day of the heist, Kamo and his men were standing in Yerevan Square, disguised as peasants and waiting for the stagecoach to pass through. When it arrived, the robbers threw bombs at the Cossack escort and began to fire at anyone standing in their way.

Official records put the death toll at three, with dozens more wounded, although other sources claim as many as 40 casualties. The Bolsheviks made off with over 340,000 rubles, but only 90,000 were in untraceable, small-denomination bills. After the robbery, the Bolsheviks tried and failed to launder the rest of the money throughout Europe, and several high-ranking members were arrested, including Kamo, who evaded a death sentence by feigning insanity.

1 Great Gold Robbery

1855

On May 15, 1855, several London firms sent gold overseas to Paris. The gold was put in boxes secured with iron bars, which were themselves placed in safes secured with state-of-the-art Chubb locks. The gold traveled by train from London to Folkestone. From the port town, it crossed the channel to Boulogne, after which it boarded a train for Paris. However, in Paris, it was discovered that 91 kilograms (201 lb) of gold had been replaced with lead shot.

The robbery would have been the perfect heist were it not for greed. One of the robbers, Edward Agar, a forger by trade, was soon arrested on another charge. He was sentenced to transportation in Australia. One of his accomplices, William Pierce, was supposed to give his share to the mother of Agar’s child, Fanny Kay. He kept it instead. In retaliation, Agar made a full confession.

Four men pulled off the heist—Agar, Pierce, William George Tester, and James Burgess. The hardest part was obtaining copies of the keys. Two of them were needed, one held in London and the other in Folkestone. That’s where Tester, a clerk at the railway office, and Burgess, a railway guard, came in.

After a few months, the gang obtained the keys they needed. Agar even went on several practice runs with Burgess to make sure everything went smoothly. All they had to do was wait for a valuable haul. On the night of the robbery, Agar and Pierce boarded the train posing as gentleman passengers, while Burgess worked as a guard and smuggled in lead shot hidden in carpetbags. The gang went to work after the train left London and replaced the gold with lead. Arriving in Folkestone, Pierce and Agar simply boarded the train for Dover while Burgess loaded the carpetbags full of gold into another train.

The jury only needed 10 minutes to convict the men. Burgess and Tester received 14 years’ transportation, but Pierce only got two years for larceny.

Radu is into science and weird history. Share the knowledge on Twitter or check out his website.