Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

10 Documents With A Profound Influence On History

History can prove hard to uncover. When delving back hundreds or even thousands of years into our past, we have to make do with whatever bits and pieces we find, hoping they can provide us with an accurate picture of a time long gone. Sometimes, we get lucky, though. Occasionally, we uncover documents that detail some of the most notable events in history.

10 The Cyrus Cylinder

In 1879, archaeologist Hormuzd Rassam was excavating in Mesopotamia when he uncovered a number of clay tablets which provided us with an unparalleled look at the ancient world. Among them was the Cyrus Cylinder, a document written in cuneiform script which, according to some, represents the oldest charter on human rights.

The cylinder was created around 538 BC, shortly after Persian King Cyrus the Great conquered Babylon. According to the cylinder, Cyrus is portrayed as a liberator. He was chosen by the Babylonian god Marduk to free the city from the reign of Nabonidus, who had perverted the cults of the gods and enslaved his own people through forced labor. Cyrus entered the city without a fight, and the Babylonian people delivered Nabonidus to him and accepted Cyrus’s kingship.

Afterward, the cylinder is written in the first person to represent Cyrus giving an edict. He abolishes the forced labor instituted by his predecessor and promises to bring back the people deported by Nabonidus and restore the religious cults and temples that were previously forbidden.

Although Iran officially recognizes the Cyrus Cylinder as a human rights charter, others claim that it was a standard proclamation made by Mesopotamian kings when taking the throne. Regardless, historians view it as the first written record of how to run a true society filled with people of different faiths and nationalities. Cyrus’s Achaemenid Empire became the largest empire of ancient history, stretching from the Indus Valley in modern-day Pakistan to the Balkans in Europe.

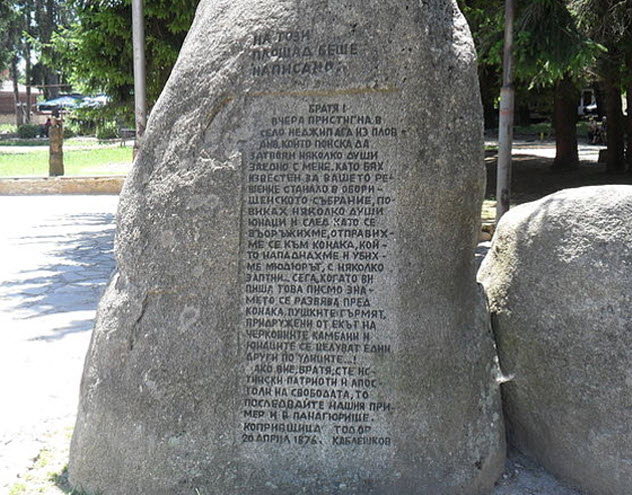

9 The Blood Letter

In late 14th century, the disintegrating Bulgarian Empire was eventually conquered and incorporated into the Ottoman Empire. Around the mid-1870s, a state of national awakening emerged from Bulgarians who sought to live in a sovereign state again. This led to the April Uprising of 1876 in which Bulgarian nationals revolted against the Ottoman government.

One of the main leaders of the uprising was Todor Kableshkov. After he and other revolutionaries defeated the Ottoman presence in the town of Plovdiv, Kableshkov wrote a letter to the insurrectionists in Panagyurishte, urging them to do the same. He signed it with the blood of a murdered mudur (Turkish official), and it became known as the Blood Letter, the symbol of the revolution.

The actual uprising didn’t go very well. The Ottoman government brought in groups of irregular soldiers called bashi-bazouks who crushed all opposition. Kableshkov himself was betrayed and captured by Turkish authorities. He committed suicide in prison.

The bashi-bazouks quickly developed a reputation for incredible cruelty and total lack of discipline. An American war correspondent named Januarius MacGahan described the atrocities of Turkish soldiers burning down entire settlements and killing all inhabitants.

This turned international opinion against the Ottoman Empire. Russia saw an opportunity to minimize the empire’s influence and, after a failed peace conference, declared war in 1877. With the help of several Eastern European nations, Russia won the war. After the Treaty of Berlin in 1878, Bulgaria became an autonomous state once again after almost half a millennium of Ottoman rule.

8 Ryo-no-gige And Ryo-no-shuge

For centuries, Japan was governed by a code of laws known as Ritsuryo that was inspired by Confucianism and the legal system enacted in China during the Tang dynasty. The Omi Code appeared in AD 668 under Emperor Tenji, becoming the first collection of Ritsuryo laws in Japan. It allegedly contained 22 volumes of administrative code, but there are no extant copies and its existence can only be inferred from notes in other documents.

Several years later, the Omi-ryo was refined into the Asuka Kiyomihara Code of AD 689. It offered improvements on the older code such as establishing the Daijo-kan, the Great Council of State that remained Japan’s highest governmental body until it was replaced by the Cabinet in modern times. At least, that’s what we infer as there are no surviving copies of this code, either.

In 701 came the Taiho Code, which was the first revision to contain criminal as well as administrative code. Again, there are no extant copies. Its successor, the Yoro Code, was compiled in 718 but wasn’t promulgated until 757. This time, we have some information due to a book called Ryo-no-gige (“Commentary on the Ryo”). Written by Japanese scholars and published in 833, the book contained almost all the administrative code of the Yoro-ryo.

A few centuries later, it was complemented by another book called Ryo-no-shuge which presented a comparative study between the Japanese and Chinese codes. Eventually, historians were able to use the extant Chinese Tang Code to piece together the penal side and compile an almost complete Yoro Code.

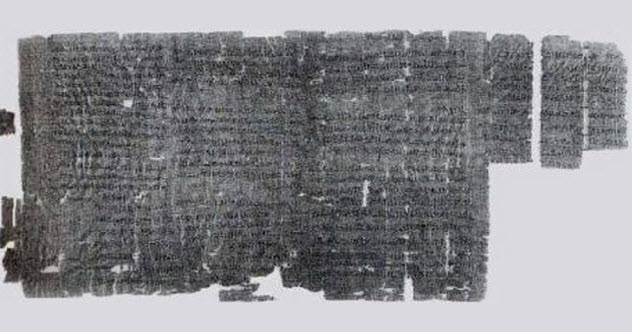

7 Deir el-Medina Papyrus

Deir el-Medina has provided us with a wealth of information on ancient Egypt. When the tombs in the Valley of the Kings were being built, this little village housed the many tradesmen, artisans, and other professionals who were employed to work on the monuments. We have already found evidence that showed the workers benefited from a primitive form of healthcare system. But Deir el-Medina was also the site of the first recorded labor strike in history.

The entire event was detailed on a papyrus by a scribe named Amennakhte. It happened around the year 1155 BC during the reign of Ramses III. Craftsmen at Deir el-Medina were complaining that 18 days had passed without receiving their rations. Therefore, they refused to work and instead sat down at the rear of the temple of Menkheperre. This also probably marks the first recorded sit-down protest in history.

The strike continued for several days as the workers urged for their complaints to be taken to the vizier. Eventually, the vizier made his way to Deir el-Medina and successfully negotiated with the strike leaders. The scribe doesn’t note the strike being anything particularly uncommon, which means that it most likely was not the first workers’ strike to occur, just the oldest one of which we have a written record.

6The Braintree Instructions

There were several events that caused the American Revolution, but one of the main issues was the taxes levied by Great Britain on the colonies without their consent—“No taxation without representation.” This concern was exacerbated in 1765 when Parliament passed the Stamp Act. It required many materials printed in the colonies to be made using stamped paper carrying a revenue stamp produced in London.

As the act was mainly an attempt to increase British revenue from the colonies, it proved massively unpopular in America and led to several protests. It also led to one of the first official protests against Parliament’s authority in North America, a document known as the Braintree Instructions.

On September 24, 1765, the town of Braintree, Massachusetts, organized a town meeting where a gathering of about 50 people unanimously signed a document destined for the Massachusetts General Court. The document decried the actions of British Parliament as a violation of the Great Charter (Magna Carta). Eventually, the Braintree Instructions were published in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Gazette. Based on the document’s popularity, the reasoning and language used in the Braintree Instructions were adopted by dozens of cities in the state protesting the Stamp Act.

The Braintree Instructions also became notable for the man who wrote them—John Adams. His “career” as a political activist was just getting started, but he would play an important role during the revolution and later become the second president of the United States.

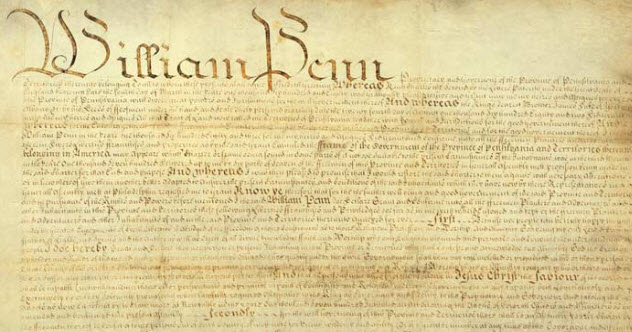

5 The Charter Of Privileges

In 1681, William Penn established the Frame of Government as a constitution for the Province of Pennsylvania. The original constitution was adopted on May 5, 1682. A new Frame of Government was adopted one year later and again in 1696, with the last one, known as the Charter of Privileges, ratified in 1701. This version of the constitution remained in effect until 1776. To celebrate the charter’s 50th anniversary, the Pennsylvania Assembly ordered a new bell for the state house which became one of the country’s most cherished artifacts—the Liberty Bell.

The legacy of Penn’s Frame of Government extends far beyond that, though. It is now regarded as an important step toward true democracy for the many liberties and rights that it provided for different religions. Although William Penn was a Quaker, he was an advocate of religious freedom who also negotiated peaceful deals with Native American tribes. Back in England, he was arrested numerous times for his beliefs and spent his jail time writing more pamphlets to further his cause.

When word of Penn’s new constitution reached Europe, it found support among those who shared his convictions. French philosopher Voltaire said that William Penn “brought down upon Earth a Golden Age” unlike any that has been before.

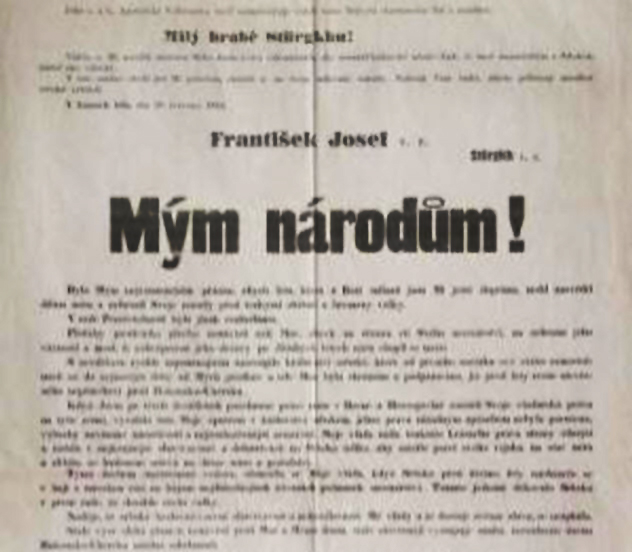

4 ‘To My Peoples’

On July 29, 1914, a manifesto titled “To my peoples” was widely distributed throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Signed by Emperor Franz Joseph I one day earlier, the manifesto officially announced a declaration of war on Serbia, signaling the start of World War I. In the document, the emperor portrays himself as a man of peace, forced into war by “incessant provocations” from the Kingdom of Serbia to defend the honor and position of his monarchy.

The title “To my people” was a common headline for war manifestos. Franz Joseph used the plural “peoples” to signify that the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a multiethnic empire consisting of two equal monarchies plus the autonomous Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia. Within days, the document had been translated into all languages of the empire and distributed as pamphlets and propaganda posters. It was also published in all the newspapers.

The document was seen as the culmination of the July Crisis. Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, many people realized that war between Serbia and Austria-Hungary was inevitable. The latter made an “attempt” at a peaceful reconciliation by issuing an ultimatum to Serbia that contained unacceptable terms, including Austro-Hungarian government representatives in Serbia, Austro-Hungarian police in Serbia, and the removal from the Serbian government of all military and civil administrators named by Austria-Hungary.

Suffice it to say that the war didn’t go as planned for Austria-Hungary. The end of the Great War brought the demise of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the fall of the Habsburg monarchy.

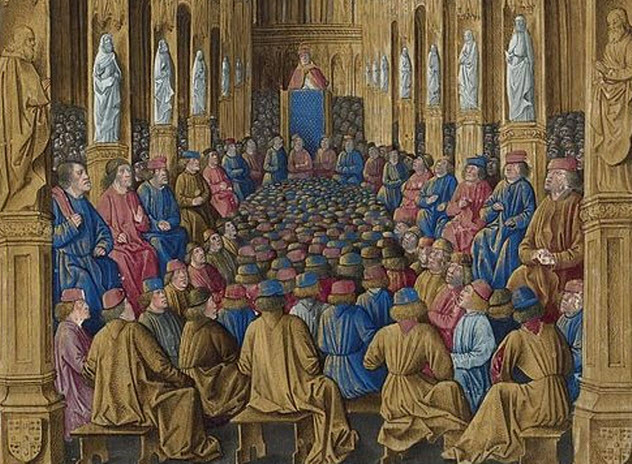

3 Pope Urban II’s Letter Of Instruction

Around AD 1095, Byzantine Emperor Alexius I Comnenus sent a request to Pope Urban II asking for military assistance against Seljuk Turks attacking his lands in Asia Minor. In response, the pope organized the Council at Clermont consisting of hundreds of clerics and nobles. There, Pope Urban gave one of the most significant speeches in history, triggering an event that would have a profound effect on Europe for centuries to come—the Crusades.

The council lasted from November 18 to November 28. Urban gave his speech on November 27, which is now regarded as the starting point for the First Crusade. The pope argued that it was time for Eastern and Western Christianity to unite against the Muslims. The following year, tens of thousands of soldiers marched east. The crusade culminated with the recapture of Jerusalem in 1099, although Pope Urban died a few weeks before word reached Western Europe.

We have six sources of information regarding the Pope’s speech at the Council of Clermont. The reliability of five of them is a matter of debate. They offered varying details on certain issues such as what kind of pardons would be granted to crusaders and whether the primary goal was helping the Byzantine Empire or retaking the Holy Land.

The sixth source is a letter of instruction written by the Pope himself in December 1095 to crusaders rallying in Flanders. It covers the Council of Clermont and remains the best source for one of the most important events in the history of medieval Europe.

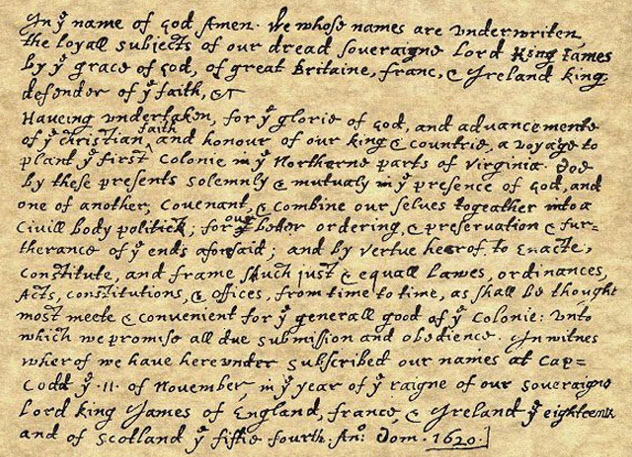

2 The Mayflower Compact

Plymouth was one of the most notable early English colonies in North America. Some of its aspects are now deeply ingrained in American culture, particularly the Pilgrims and the Thanksgiving celebration. Back then, Pilgrims were typically referred to as Separatists—devout people who had fled England for a new place where they could practice their religion as they saw fit. Their iconic 1620 trip aboard the Mayflower is another essential tale of America folklore.

What’s usually forgotten is that the Pilgrims were actually a minority aboard the Mayflower. Over half of the more than 100 passengers plus the 25 crew members were “strangers” or non-Separatists. Originally headed for Virginia, the Mayflower had to settle for new land due to dangerous storms and a shortage of supplies. Worryingly, the Separatist leaders realized that most strangers had no interest in following Pilgrim rules once a settlement was established. In the words of a stranger, they were free to “use their own liberty.”

This resulted in the drafting of the Mayflower Compact, the first frame of government written and enacted in the United States. All men had to sign it before going ashore. The document granted authority to a “Civil Body Politic” to enact just and equal laws, but as the governing body consisted mostly of Separatists, it ensured that they stayed in power. Although the Mayflower Compact was not a constitution, it formed the basis for Plymouth’s government and remained in force until 1691 when the whole colony was absorbed into Massachusetts Bay Colony.

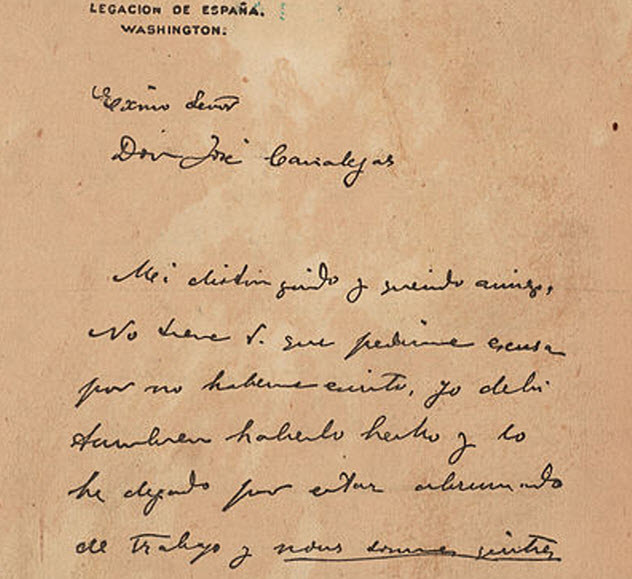

1 De Lome Letter

On April 25, 1898, war broke out between the United States and Spain, lasting for over three months and ending with an American victory. It was followed by the Treaty of Paris, which was heavily in America’s favor. Spain was forced to relinquish Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, thus losing all of its overseas territories except for a few in Northern Africa. Many see this as the end of the Spanish Empire, once known as the “empire on which the Sun never sets.”

Before the war, people in America were divided on the issue. Yellow journalism pioneers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were in favor of war and were accused of using the media to incite the public. In this regard, Hearst hit pay dirt in February 1898 when he acquired the De Lome letter.

Enrique Dupuy De Lome was the Spanish ambassador to the United States. He wrote an unflattering letter to Spain’s foreign minister about America’s involvement in Cuba. It described McKinley as weak and a low politician. However, Cuban revolutionaries intercepted the letter. Eventually, Hearst found out and published it in the New York Journal with the headline “The Worst Insult to the United States in Its History.” The scandal outraged the American public, and they demanded action. Two months later, they got their wish.

On the Spanish side, the war cost Spain international power and prestige, but the country did experience an intellectual rebirth due to a new wave of writers, poets, and philosophers known as the Generation of ’98.

Radu is into science and weird history. Share the knowledge on Twitter, or check out his website.