Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

10 Mystics Who Served World Leaders

Long before the modern scientist took charge of our pursuit of the unknown, we had an entirely different figure at the helm—the mystic. Alchemists, fortune-tellers, and sorcerers of all kinds claimed to have answers to the questions on our minds. Though many were simple charlatans, knowingly spreading lies in the pursuit of wealth and fame, others truly believed in the magic they professed to wield.

Throughout history, world leaders have sought out those that practice the occult, hoping to gain from their esoteric knowledge and in some cases, their alleged mystic power. Here are ten mystics, occultists, and so on who served the rich and powerful.

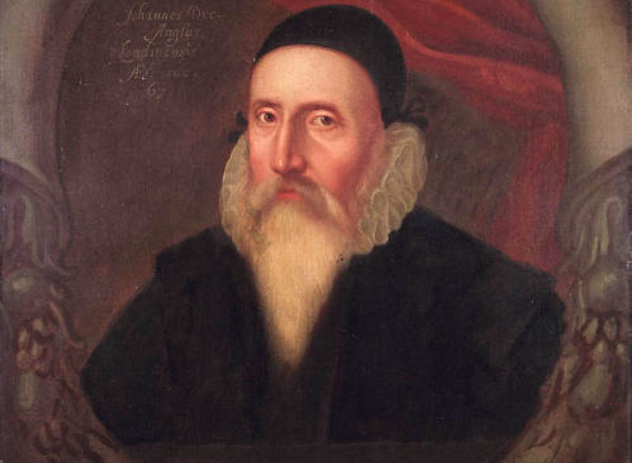

10 John Dee

During the late 16th century, John Dee straddled the fence between science and magic, devoting his intellect to the fields of mathematics and astronomy as much as alchemy and divination. Born in London in 1527 to a member of Henry VIII’s court, Dee found himself in the company of royalty from a young age.

Catching the interest of Queen Mary and the young Elizabeth I, Dee began his career as a reader of horoscopes. However, not everyone was as fond of his work as the queen. In 1555, Dee was arrested and tried for treason, accused of “calculating” the horoscopes of the queen and her daughter. Fortunately, Dee managed to convince both the court and the church of his innocence.

After Elizabeth took the throne, Dee continued to serve as her advisor and mystic guide. With his new position, he was able to develop relationships with royalty all across Europe, including Emperor Rudolph II, a renowned patron of alchemists and sorcerers.

Later in life, as Dee’s influence began to wane, he traveled to Europe in search of the Philosopher’s Stone, an alleged source of immortality. He returned empty-handed, but he believed that what alchemy he had learned could at least resolve the economic crisis facing his homeland. Unfortunately, England’s tolerance for the occult had faded during his absence, and he resigned himself to a teaching the mundane at the University of Cambridge. Dee passed away in 1609.

9 John Lambe

In the early 17th century, John Lambe, an astrologer and supposed necromancer, found himself working for George Villiers, first duke of Buckingham, a favorite companion of King Charles I. Over the years, Lambe amassed a notorious reputation; Londoners often referred to him as “the Duke’s Devil,” believing him capable of conjuring spirits, raising the dead, and casting hexes upon his enemies. Villiers followed Lambe’s advice, and King Charles listened to Villiers’s, so Lambe became the subject of a popular chant:

Who rules the Kingdom? The King.

Who rules the King? The Duke.

Who rules the Duke? The Devil!

As evidenced by his nickname, Lambe was not well-liked by the common folk. Nonetheless, anyone who came forward with accusations of his wrongdoing were promptly dismissed. Finally, in 1627, Lambe was accused of raping an 11-year-old girl and sentenced to death. Neither the king nor the duke could prevent it. After his death at the hands of a mob, Lambe became a popular subject of literature and plays.

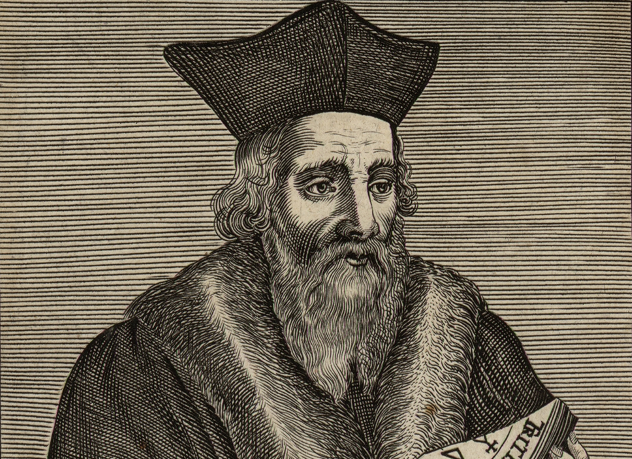

8 Edward Kelley

Professing to be capable of both summoning spirits and turning base minerals into gold, Sir Edward Kelley was quite popular within occult circles and became a trusted advisor to emperors and fellow mages alike. Working alongside John Dee, Kelley persuaded Europe that his visions would lead him and his fellow alchemists toward the fabled Philosopher’s Stone.

After earning a knighthood while living in the care of Emperor Rudolph II, Kelley claimed that he had successfully transformed stone into gold. Unfortunately, Kelley lacked evidence. Seeing this, Rudolph was incensed and imprisoned Kelley in a castle outside Prague until he could provide results. After an unsuccessful escape attempt that resulted in a broken leg, Kelley died in prison in 1598, surrounded by the same stone he had failed to transform.

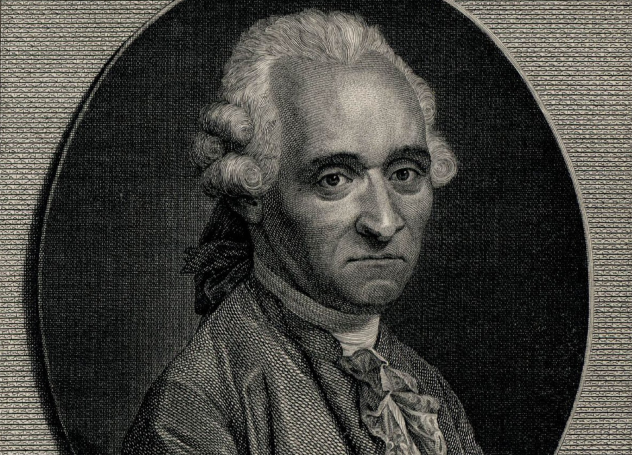

7 Antoine Court De Gebelin

Born on January 25, 1725, Antoine Court de Gebelin became known as the man who first advocated the tarot as a source of existential wisdom. Court wrote of his belief that early civilizations, specifically ancient Egypt, existed in a state of technological and spiritual enlightenment.

His perspective on the tarot was the most immediately groundbreaking. Court believed that the tarot held esoteric secrets of the Egyptians, transcribed by ancient priests from the “Book of Thoth” into the images on the cards. It took only a few years for the belief to catch on, and fortune-telling by tarot was born. In 1784, Court died quietly in Paris.

6 Roger Bolingbroke

Immortalized by Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Roger Bolingbroke’s legacy outshines his humble origins. He served under Eleanor, duchess of Gloucester, as a cleric and magister, tending to the household of her husband, who was next in line to the British throne. In October 1440, Bolingbroke and two others, John Home and Thomas Southwell, cast a horoscope predicting that King Henry VI would die from terrible illness.

Rumors of the prediction eventually reached the king’s ears. Taking the visions as a curse, he charged the trio, as well as Duchess Eleanor, with conspiracy to assassinate him. All four admitted to some level of guilt. Bolingbroke was hanged, drawn, and quartered. Home and Southwell met similar fates. Eleanor was shipped off to the Isle of Man.

5 Evangeline Adams

Evangeline Adams was perhaps the first nationally renowned US fortune-teller. Born in 1868, Adams traveled the world, taking an interest in Eastern spiritualism as well as astrology. After moving to New York, Adams began to practice fortune-telling professionally. She was able to turn her practice into a massive success, despite the fact that fortune-telling was illegal in New York at the time. Adams was arrested three times but never convicted.

Wall Street took a particular interest in Adams. Before the market crash of 1929, thousands followed her predictions published in her newsletter. Her financial advice was accepted by both minor investors and major institutions alike. After the crash, Adams’ popularity took a turn, with many blaming her for leading investors astray. She died shortly after in 1932.

4 Jabir Ibn Hayyan

While the prominent alchemists of Europe sought to create gold, their predecessors in the Middle East sought something entirely different—takwin, the means “to create life.” Jabir ibn Hayyan, an eighth-century polymath, is credited with successfully creating this synthetic life.

Jabir’s works contain numerous recipes for creating insects, serpents, and even humans, all within an alchemist’s laboratory. Writing primarily for Caliph Harun al-Rashid and his governors, Jabir hoped that his work would serve to further the Islamic understanding of existence and nature. Although Jabir’s goals were primarily mystical, he also managed to plant the seeds of modern chemical classification.

3 Ulrica Arfvidsson

During the reign of Gustav III, fortune-telling was a flourishing trade in Sweden. One of the most prominent fortune-tellers was Ulrica Arfvidsson, a mysterious woman later popularized in Giuseppe Verdi’s The Masked Ball. Born in 1734 to a palace caretaker, Arfvidsson grew up constantly surrounded by royal gossip, something that would suit her well later in life. Unlike most fortune-tellers, Arfvidsson relied on a robust network of informants, allowing her to draw conclusions that seemed to originate in magical power.

Arfvidsson is most well-known for her prediction of Gustav III’s death. In 1786, Gustav came to her in disguise, hoping to learn his future. After seeing through his ruse, Arfvidsson told him of his past, his present, and finally, his future. She warned him that he should fear a man in a mask, armed with a sword. Gustav III was assassinated at a masked ball in 1792, though the man who killed him was armed with a gun. Arfvidsson’s fame eventually waned, and she died in poverty in 1801.

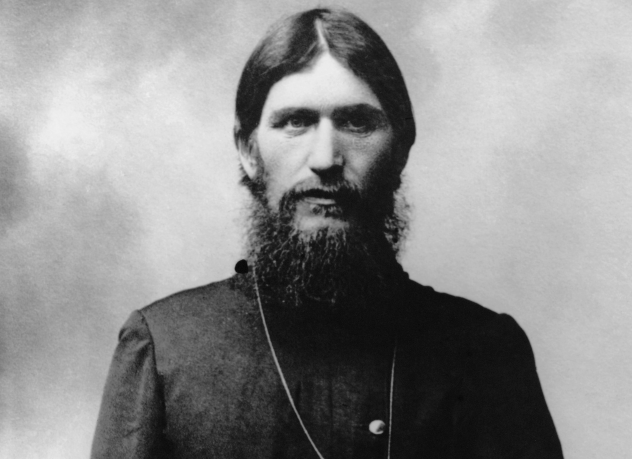

2 Rasputin

Rising to prominence in the early 20th century, a time of extreme unrest in Russia, Grigori Rasputin wandered the country, convincing rich and poor alike that he was capable of healing the sick by faith alone. After being introduced to Tsar Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra in 1906, Rasputin was invited to heal the daughter of Prime Minister Pyotr Stolypin.

A year later, he was called upon again to heal the tsar’s son, Alexei, who suffered from painful internal bleeding. Rasputin convinced the tsar and his wife that he could save their son. It’s believed that he did so by ceasing the administration of aspirin, a “miracle drug” that worsened Alexei’s Hemophilia B by thinning the blood and promoting bleeding.

Though many in the Russian aristocracy saw Rasputin as a prophet, others saw him as a fraud and heretic. Rumors began to spread of his drunken exploits, and worse, that Alexandra allowed him into her bed whenever he liked, alongside all the other ladies of the town seeking “private blessings.” Rasputin quickly became a point of shame for the Russian aristocracy. He was assassinated at Moika Palace in December 1916.

Unfortunately for the tsar, losing Rasputin meant losing a valuable scapegoat for his subject’s grievances. The public soon turned against Nicholas and executed him and his family in 1917, their bodies paving the way to what would become the Soviet Union.

1 Alexis Vincent Charles Berbiguier De Terre-Neuve Du Thym

While many mystics have found fame and validation working for world leaders, not all were so successful. Alexis-Vincent-Charles Berbiguier de Terre-Neuve du Thym, a man whose name perfectly matches his personality, was one of these failures.

Berbiguier was a demonologist who believed that he could perceive, communicate with, and combat the demons that haunted the Earth. Proclaiming himself the “Scourge of the Imps,” he spent his life trying to educate world leaders about the dangers that surrounded them.

After a series of confrontations with the authorities, including spreading sulfur and thyme throughout Paris in an attempt to scare off the imps, Berbiguier was committed to hospice for psychotherapy, with little effect. He went on writing, styling his caretakers as “servants of the imps.” Later in life, he sought out and attempted to burn much of his printed work for reasons unknown.