Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

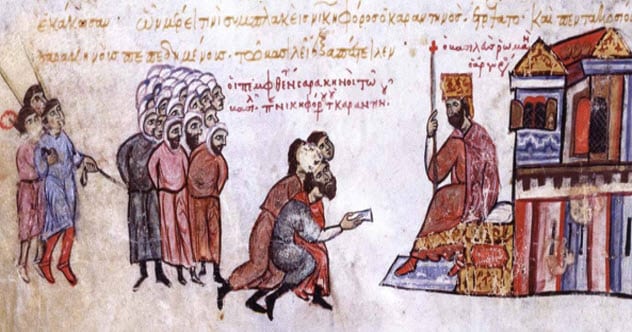

10 Dark Secrets Of The Byzantine Empire

For 1,000 years after the Western Roman Empire fell, the Eastern Empire of Byzantium stood strong. Ancient and powerful, the Byzantine court soon became known as a warren of intrigue and secrets. No one was safe, and no one could be trusted.

10Assassinations

Since the Byzantines always felt that an unpopular ruler could be replaced, a number of emperors died violent deaths.

Constans II was clubbed to death with a soap dish while resting in his bath. Michael III lost both his hands trying to block a sword. Nikephoros Phokas was warned of a plot and ordered a search of the palace, but his wife had hidden the assassins in her bedroom, which no guard would dare to search. They stabbed him to death that night.

At least, Leo the Armenian went out in style. Ambushed on Christmas Day by assassins disguised as a choir of chanting monks, he seized a heavy cross from the altar and battled them around the Hagia Sofia until his arm was cut off and he was struck down. Less romantically, the killers then threw his corpse into a toilet.

9Mutilation

The Byzantines believed that disfigurement disqualified candidates for the throne. As a result, emperors often mutilated their rivals rather than killing them outright. Blinding was popular, as was cutting off noses and tongues. In later years, castration became the most common practice.

In some ways, mutilation was considered kinder than execution. John IV Laskaris lived for 40 years after being blinded. But it was undoubtedly brutal. Empress Irene had her own rebellious son blinded in the room where she had given birth to him. The youth died of his wounds a short time later.

However, it was sometimes possible to come back from mutilation. Basil Lekapenos was castrated as a boy to prevent him from causing trouble when he grew up. With the throne closed to him, Basil became a powerful courtier and ruled through a series of puppet emperors.

8The Noseless Emperor

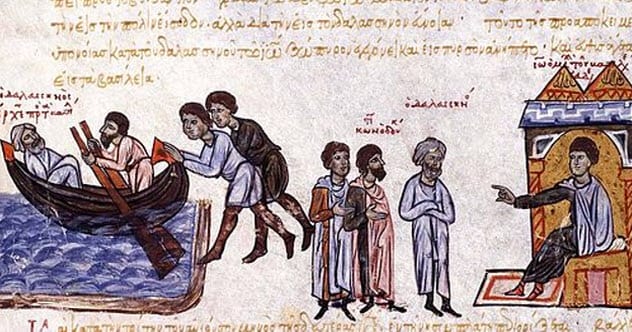

The terrifying Justinian II was first overthrown in AD 695. The rebels cut off his nose and slit his tongue down the middle before exiling him to the Crimea. Undeterred, Justinian escaped to the land of the Khazars and began plotting a return to power. The new emperor bribed the Khazars to murder their guest, but Justinian was warned and personally strangled the assassins before escaping to Bulgaria in a fishing boat.

Forging an alliance with the Bulgarian khan, Justinian returned to Constantinople and led an army through the sewers and into the city where he took a terrible revenge on his enemies. Regaining the throne, he ruled for another six years, wearing a golden nose and using an interpreter to translate the gurgles from his ruined tongue.

His cruelty eventually grew too much, and he was overthrown again in 711. This time, they killed him.

7Intrigue

Today, the word “Byzantine” can refer to an atmosphere of confusion and intrigue, and that was certainly true of the court in Constantinople. There, eunuchs and courtiers jockeyed for influence and emperors ruled through powerful favorites.

In one ninth-century example, the eunuch Staurakios helped Empress Irene overthrow and blind her own son. Staurakios himself was soon forced from power by the eunuch Aetios, who schemed to make his brother emperor. But Aetios failed to guard against the finance minister Nikephoros, who orchestrated a coup and reigned as emperor until the Bulgarians converted his skull into a drinking cup.

This atmosphere of intrigue lasted until Constantinople fell. Even as the Ottomans massed outside the walls, Grand Duke Loukas Notaras was reportedly scheming to secure lucrative court positions for his sons.

6Civil War

In the ninth century, Michael I was forced to resign by a trio of his generals: Leo the Armenian, Michael the Amorian, and Thomas the Slav. Leo became emperor. But when he fell out with Michael, the Amorian’s followers infiltrated the Christmas service and hacked Leo to death. Thomas the Slav rose in revolt against Michael, sparking a massive civil war which badly weakened the empire against the Arabs.

Similar problems arose in the 10th century when Bardas Phokas’s rebellion was put down by General Bardas Skleros. When the eunuch Basil Lekapenos schemed against Skleros, he started his own revolt in self-defense. Lekapenos countered by releasing Phokas from prison and putting him in command against Skleros.

Phokas defeated Skleros in single combat and destroyed his forces. But Phokas, Skleros, and Lekapenos then teamed up against the young Basil the Bulgar-Slayer. Typically, they soon fell to infighting and Basil successfully secured power. He later became famous for blinding thousands of prisoners and sending them back to Bulgaria, where Tsar Samuel promptly died of horror.

5The Purple-Born

The Byzantines had long considered purple the imperial color, with only members of the royal family allowed to wear certain purple dyes. Eventually, the emperor built a special room with walls made of the precious purple stone porphyry.

Imperial children born in this room were dubbed porphyrogennetos (“purple-born”). They were immensely prestigious and weren’t supposed to marry outside the empire, although Vladimir of Kiev famously demanded a Purple-Born bride as the price for military aid and his conversion to Christianity.

The Purple-Born also attracted great loyalty from the common people. Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos was overthrown as a boy, but his Purple-Born status protected him and he was allowed to remain as co-emperor for 24 years.

When Basil II died, the only remaining Purple-Born were the sisters Zoe and Theodora. The citizens of Constantinople rioted at every attempt to remove them from power, and the pair dominated the empire until Theodora’s death in 1056.

4Riots

As citizens of the greatest city on Earth, the people of Constantinople were never afraid to express themselves, often through violence. In the most famous example, fans of the Blue and Green chariot racing teams united to riot against Justinian I.

The emperor was prepared to flee, but the day was saved by his wife, Theodora, who proclaimed that she would rather die an empress than live as a commoner. The rebels were subsequently massacred.

Not all riots destabilized the empire. One particularly bloody civil war was effectively ended by a prison riot. Megaduke Alexios Apokaukos was inspecting his new jail when the political prisoners ran amok and murdered him, crippling his faction.

The assertive tendencies of Constantinople’s citizenry survived the Ottoman conquest, and many a sultan cowered inside the Topkapi Palace while an enraged mob tore his vizier to pieces.

3Castration

Eunuchs served the Byzantine state in every capacity, from courtiers to priests to generals. (The eunuch Peter Phokas became famous for defeating a Scythian warlord in single combat.) They were perceived as nonthreatening because they had no children to inherit their status.

However, eunuchs like John the Orphanotrophos (manager of Constantinople’s orphanage) became notorious for leveraging their brothers into high office. John himself grew so powerful that his whole family had to be castrated and exiled by a nervous emperor.

Castration was technically illegal in the empire. As a result, many eunuchs were enslaved outside the empire as young boys and then castrated just before they were brought across the border. But it wasn’t unknown for impoverished Byzantine parents to castrate their sons in the hope that these boys would grow up to secure lucrative positions at court.

2Sex Slaves

Multiple sources from the period allege that eunuchs were frequently used as sex slaves because they maintained their youthful looks. This was officially forbidden, but the church struggled to find a way to stop it without condemning slavery (and thereby the emperor).

The problem is illustrated in the 10th-century Life Of St. Andrew The Fool, which basically puts the blame on the eunuchs. A character does point out that “if a slave fails to obey, you surely know how much he will suffer, being maltreated and beaten.”

But Andrew insists that “if the slaves do not bow to the abominable passions of their masters, they are thrice blessed, for thanks to the torments you mention, they will be reckoned with the martyrs.”

1The Zealots Of Thessalonica

In 1341, the empire was undergoing one of its regular civil wars. The new emperor was nine years old, and his father’s friend John Kantakouzenos had been appointed regent. The boy’s mother, Anna, and Megaduke Alexios Apokaukos formed an alliance to usurp the regency, sparking a massive conflict.

But this time, something different happened. In the city of Thessalonica, the common people seized control from the aristocracy. Calling themselves “Zealots,” these revolutionaries championed the rights of the poor. Accounts from the time claim that violent mobs of Zealots attacked and slaughtered the rich.

The Zealot council ruled Thessalonica for the duration of the civil war. For a time, they swore allegiance to Megaduke Apokaukos, but they remained hostile to the aristocracy and eventually asserted their independence by murdering his son.

The revolution was only put down after John Kantakouzenos became emperor. Some of the Zealots invited the Serbian king Stefan Dusan to take the city, but others found this unpatriotic and fighting broke out. Kantakouzenos took the city easily and executed the leading Zealots.