Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Holy Hairstyles

For millennia, people have used hair as a social identifier. Frequently, these grooming techniques become charged with religious meaning. A hairstyle can signify a covenant, or it can be part of a ritual cleansing. So long as people have hair, it will continue to have spiritual significance.

10Jata

In Hinduism, rishis and sadhus wear matted locks called “jata” as a sign of commitment to escaping the cycle of rebirth. These matted locks signify a covenant between the wearer and Shiva, the god of destruction and regeneration. They are part of a larger commitment to aesthetic life including renunciation of worldly possessions and celibacy.

Jata are often worn up, in a bundle that resembles a turban. Maintenance is more challenging than most assume. These locks must be washed every two to three days to avoid lice infestation. In southern India, some women known as Shiva Sathulu—or Shiva’s wives—wear jata as a sign of their devotion to their divine husband. Some theorize that matted locks have been worn in India for 2,500 years.

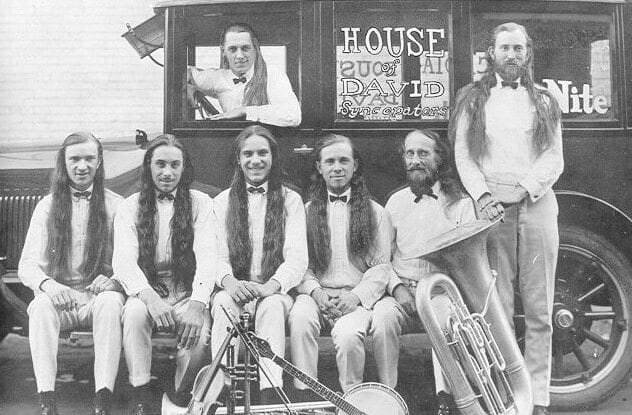

9House Of David

The House of David was an apocalyptic cult founded in Michigan in 1903. Benjamin Franklin Purnell, a self-proclaimed messenger of God, sought to reunite the 12 tribes of Israel in preparation for the Messiah’s return. Members donated their worldly goods to the cult and abstained from sex, meat, intoxicants, and cutting their hair. Their grooming advice derived from Leviticus 19:27—“you shall not round off the hair on your temples or mar the edge of your beard.”

In 1914, Purnell started a baseball team as a recruiting tool and a way to kill time before the apocalypse. In a clean-cut era, the team became a sensation, with flowing beards and hair that reached their belts. Sold out stadiums came to see the House of David play “pepper”—a “trick” version of baseball. They tossed balls around their back, through their legs, and used sleight-of-hand to hide balls in their beards.

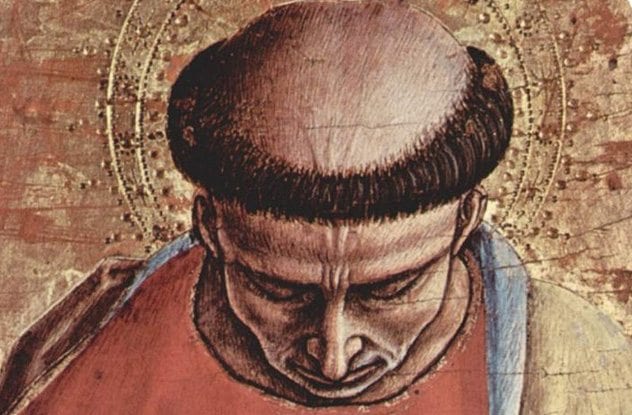

8Catholic Tonsure

Tonsure is the hairstyle associated with Catholic monks. It derives from the Latin word “tondere” meaning “to shear.” Its origins are unclear. In the Medieval Church it became the rite performed when a monk entered into a sacred order. Novices had their hair cut short upon entering a monastery. Once the monk took their vows, the hair was shaved at the top of the crown.

Other styles competed with Peterine (Roman tonsure). Celtic tonsure was worn in the pre-Christian Ireland and involved shaving the front of the head from ear-to-ear. During the seventh century, fierce debate raged about its validity. Monks in Bayeux came into conflict with local authorities when they adopted this alternative style. The Church ultimately condemned Celtic tonsure, claiming the magician Simon Magus wore it.

7Kesh

Members of the Sikh faith live by the five Ks: kirpan (steel sword), kaccha (cotton underwear), kanga (wooden comb), kara (steel bracelet), and kesh (uncut hair). Long hair is a sign of strength and holiness. Keeping the hair natural symbolizes faith in the wisdom of Waheguru—the Sikh god. Moving beyond vanity is viewed as a sign of spiritual maturity. This style, which derives from the 10th Guru, Gobind Singh, provides group solidarity. As the saying goes, “one should only bow their head to a guru, not a barber.”

Sikh women are subjected to the same grooming restrictions as men. They are not allowed to cut any hair on their body—not even their eyebrows. Bollywood and Western media have a powerful impact on expected norms. Many Sikh women have abandoned the rigorous discipline for the popular conception of beauty.

6Pe’ot

Many people associate sidelocks known as pe’ot as a strictly Hasidic style. However, followers of the tradition believe all Jewish people should wear them. The practice derives from the same passage in Leviticus sited by the House of David. The Torah is unclear why the practice should be followed. Many believe it was a means of separating themselves from idol worshipers—known shavers. Others claim it simply emerged to differentiate men and women.

Pe’ot customs vary based on mystic teachings and community norms. Some tuck them behind ears, others wrap them around the ear or twist them into ringlets. Some Kabbalistic circles believe the beard is imbued with magical power. They make effort to separate pe’ot from beard hair—believing they have different mystical attributes.

5Pabbajja

Pabbajja means “the going forth.” It is the Buddhist rite of initiation where a layman becomes an ascetic. This outgoing is the transition from home to homelessness. As part of the process, the initiate shaves their head and beard. In Theravada countries, tradition holds that boys undergo Pabbajja at puberty. In Tibet, China, and Japan it occurs later, usually around age 20, after a probationary period.

During the rite, initiates chant mantras on the transitory nature of the human form. These involve the specific recitation of “hair of the head” and “hair of the body” over and over again. Once the ritual is complete, the initiates don a saffron robe and venture out in the world. Generally, this means joining a monastery, rather than becoming a wandering mendicant.

4Chudakarana

Chudakarana is one of the important rituals in Hinduism. It literally means “tonsure” and refers to a child’s first haircut. According to scripture, the early hair represents a continuation from the past life. Chudakarana is a symbolic departure from the old existence into a new life. The Grihya Sutra states the rite should not be performed before children reach one-year-old. Once a child hits age three, they are too old.

In Chudakarana the entire head is shaved, except for the crown. This remaining tuft is known as the “chuda” or “shikha.” It is the priest’s job to arrange the tuft in accordance to the child’s unique “gotra”—or “family of ancestors.” This ancient ritual is often performed in sacred sites. Frequently, the hair is offered to the Ganges.

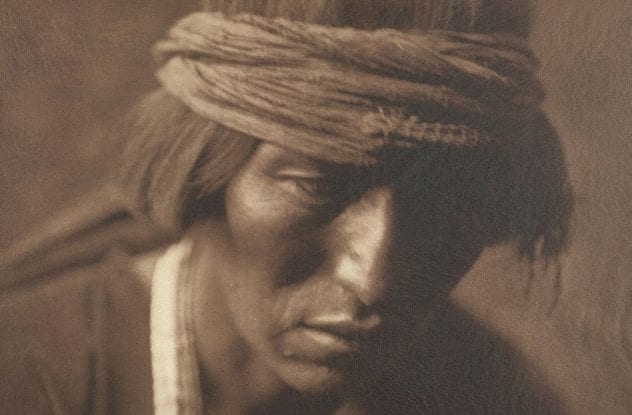

3Navajo Hair

One of the most universal beliefs of Native Americans is that hair is sacred. To the Couchiching First Nation, it is a physical symbol of spiritual commitment. Some, like the Dine, cut their hair in morning. To the Navajo, hair represents memory. Many believe it also imbues wearers with supersensory abilities.

In the mid-20th century, Navajo were recruited in the army as code talkers and trackers. When individuals well documented with having “outstanding, almost supernatural tracking abilities” failed in the field, they blamed hair. The Navajo recruits indicated that the military issue haircuts prevented their finer senses of perception from working properly.

Few scientists believe that the dead keratin cells of hair transmit and extra-sensory perception. However, hair is connected to the same skin receptors that gauge temperature, register a breeze, or serve as a warning against bugs.

2Metzora

Tzara’as is a mysterious skin disease mentioned in the purity laws of The Torah. The disease runs more than skin deep, and it makes its bearer ritually unclean. Tzara’as is viewed as a manifestation of an internal moral condition. The only way to combat this sickness is through religion. Only Kohanim priests could diagnose and treat the illness.

The afflicted, known as metzora, are bathed and shorn all over their body. They can return home. However, for a week they can still spread the illness and must abstain from sexual contact. After a full seven days, the metzora return and are shorn of all external hair once again. Finally, the afflicted are declared “pure.” This bath and shaving symbolize the metzora as infants, with their whole lives ahead. They shed baggage along with their hair.

1Dreadlocks

Dreadlocks became known worldwide after Bob Marley’s ascendancy to superstardom. The reggae singer’s iconic hair was deeply woven with his Rastafari beliefs. Dreadlocks are a sign of African identity and a symbolic covenant to fight against “Babylon”—the white European imperialist world. According to Rastafari tradition, Jesus will return as the Lion of Judah. Practitioners adopted the hairstyle to signify a lion’s mane.

Dreadlocks have become the frontline of arguments about racial identity. In September this year, the 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that refusing to hire someone because of their dreadlocks was legal. The employee, Chastity Jones, claimed this was a violation of the Civil Rights Act. She argued dreadlocks are considered a “racial characteristic.” However, the court ruled that they are not an “immutable physical characteristic.” Dreadlock restrictions are now in place at some schools.

Abraham Rinquist is the Executive Director of the Winooski, Vermont, branch of the Helen Hartness Flanders Folklore Society. He is the coauthor of Codex Exotica and Song-Catcher: The Adventures of Blackwater Jukebox.