Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

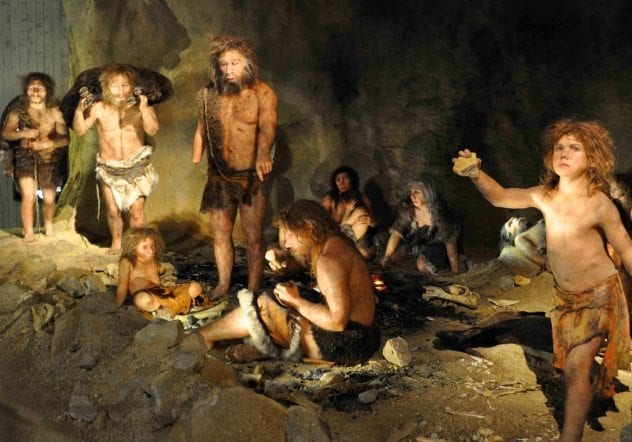

Top 10 Remarkable Traits Neanderthals Have In Common With Modern Humans

The line separating Homo sapiens and Neanderthals is thinning. Scholars are no longer even sure if the two are different species. While Neanderthals are long-extinct (and possibly a subspecies of modern humans), archaeology is proving that they had a lot in common with people today. From makeup to personal quirks, keeping the kids occupied, and fighting disease with medicine, Neanderthals showed remarkably humanlike innovation and emotions. Their extinction around 24,000 years ago remains an enduring mystery.

10 Their Cognition Included Symbols

What cognitive abilities Neanderthals had is still being debated. Scientists in Crimea found an interesting article at the Zaskalnaya VI site, once a Neanderthal haunt, in 2017. A small bone belonging to a raven appeared to have been decorated. While not an elaborate carving, two notches nevertheless caught researchers’ attention.

To find out if the pair was a symbolic addition with the purpose of making other nicks line up evenly, volunteers replicated the marks on turkey bones. The domestic species was chosen because its bones matched the size of the Zaskalnaya raven. The turkey samples matched the ancient artifact quite closely.

Finding altered bones at Neanderthal sites is nothing new. Several have been discovered in recent years, leading to the notion that instead of being accidental grooves caused by butchering, the decorated bones were used as jewelry or ornaments. The Zaskalnaya bone is the first, however, to indicate that Neanderthals included symbolic patterns in their carvings.

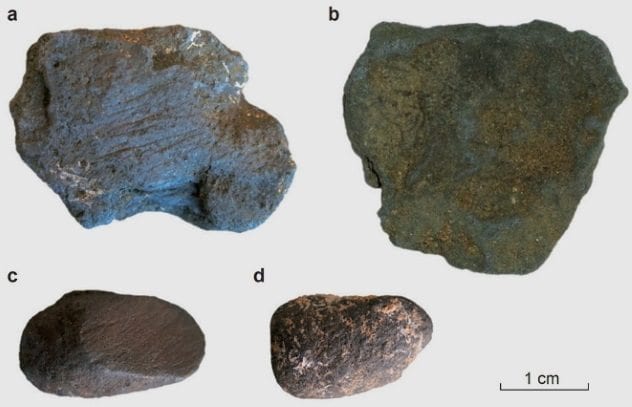

9 Fire-Making Minerals

Another remarkably brainy moment was discovered at in France in 2016. It would appear that several groups living in what is now the Pech-de-l’Aze archaeological site collected manganese dioxide to make fire. Looking at the mineral, it is not immediately obvious that it can greatly assist anybody living in a cave to get some warmth. By itself, the material is noncombustible. Yet, over and over, 50,000-year-old “blocs” kept turning up during excavations.

At first, the chunks were sidelined as black pigment. That made little sense in the long run. If Neanderthals felt the need to color anything black, they had easy access to ample soot and charcoal from their hearths. Manganese dioxide would be the more strenuous choice, since they had to go out and collect it, whereas soot was already available at home. There had to be a different purpose for gathering the oxides.

Tests proved that the mineral, when ground, creates a more stable and lasting fire. Somehow, Neanderthals figured out that a non-burning piece of earth could facilitate fire-making. This would explain why they made the effort to harvest this precious resource.

8 They Had Personal Collections

Once upon a time, about 130,000 years ago, a Neanderthal fancied a peculiar pebble. He or she picked it up and took it home. “Home” was a cave in modern Croatia, at the Krapina archaeological site. The cave was sandstone, while the rock was a brown piece of limestone with black patterns. Among the 1,000 stone pieces extracted from Krapina, nothing matched the pebble. The striking rock probably piqued the curiosity of the Neanderthal who found it.

In 2015, a collection of eagle talons was found at the same site. The talons had been carved and made into a piece of jewelry. In other locations, Neanderthals gathered shells and even adorned them with pigments.

The limestone rock was originally found during excavations that lasted from 1899 to 1905 and was forgotten until the same team who found the talons researched the site’s past finds. That’s when they found the rock, which appeared to have no purpose other than to look pretty. It had no modifications as a tool or piece of jewelry. Measuring about 13 centimeters (5 in) long, 10 centimeters (4 in) high, and 1.3 centimeters (0.5 in) thick, it was likely found a few miles north of the cave, where similar limestone exists.

7 Their Homes Had Hot Water

A Neanderthal sipping a prehistoric drink while lounging in his Jacuzzi probably isn’t the first guess of what luxuries existed for cave dwellers. While nobody can say for sure what got sipped and if they lounged, what is certain is that some Neanderthal caves probably had artificially heated water sources. A 60,000-year-old cave in Barcelona, Spain, had already produced a wealth of information about the domestic lives of these interesting hominids, but what stole the show was a hole found near the hearths in 2015. Archaeologists believe the feature was an aid to give the community hot water.

This particular group of Neanderthals was well-organized. They had separate areas for sleeping, trash disposal, and tool creation and even had an abattoir. Some of the animal remains included deer, goats, and horses. Far from living in a disorganized setting, the Barcelona Neanderthals organized their homes, sorted chore-specific spaces, ate well, and boiled water to make their lives more comfortable.

6 Herbal Knowledge

The study of one Neanderthal has revealed that they weren’t strangers to illness or to herbal remedies. Found in El Sidron, Spain, the individual suffered from several complaints. When microbiologists examined the tartar on its teeth in 2017, they got a good look at some nasty bugs and how this Neanderthal dealt with falling sick.

They found the pathogen Enterocytozoon bieneusi, which meant that the patient endured vomiting and diarrhea. For this, a treatment of ingesting antibiotic-producing molds was probably the go-to medicine. Researchers detected the DNA of Penicillium rubens between the teeth. A dental abscess, likely caused by a subspecies of Methanobrevibacter oralis, appeared to have been treated with prehistoric painkillers. In the same sample were traces of salicyclic acid, which today is the active ingredient in aspirin.

The presence of Methanobrevibacter was interesting. In modern times, these bacteria are spread through saliva. The Neanderthal strain originated 125,000 years ago, when interbreeding between them and Homo sapiens is believed to have occurred. The oral microorganism was transferred across the species, most likely in the way it would be today, through eating together or kissing.

5 Body Glitter

Neanderthals beat the modern body glitter craze by many thousands of years. In 2008, a team of archaeologists investigated another Spanish Neanderthal location. While working at a cave called Cueva Anton, an undergraduate student found what looked like a wall fossil. Only when it was later cleaned did it become clear that it was a pierced scallop shell. Red and yellow pigment particles colored its surface. This prompted a closer look at artifacts found in another nearby cave in 1985, especially an oyster shell that contained pigment. An examination of the 50,000-year-old oyster identified the pigment to be a mix of minerals such as haematite, lepidocrocite, charcoal, and pyrite.

The dark-reddish concoction provided an interesting insight into Neanderthal behavior. It was a complex recipe, made from pigments that required some work to collect, indicating that it was important to them. While researchers readily admit that it cannot be proven, slapping something like this together only makes sense if it was a type of body powder. The substance had a dark glitter and was likely used as cosmetic or symbolic makeup.

4 Complex Language

Many cartoons display cavemen as grunting, nonspeaking creatures, and for most, the image has stuck. Not many consider what language Neanderthals spoke, if they even had words, or how simple or advanced their spoken communication was. Things took a turn in 1989, when a 60,000-year-old Neanderthal hyoid bone was discovered in Israel. This bone is connected to the tongue and helps with speech. In other primates, it’s placed in such a way that they cannot vocalize like people, but the Neanderthal hyoid was nearly identical to that of modern humans.

In 2013, computer modeling showed that Neanderthal hyoids were used in a similar manner to humans, and this was enough evidence to suggest that Neanderthals could not only talk but that they were capable of complex language. Previously, this was considered a unique trait of modern humans. More research is needed to prove beyond a doubt that Neanderthals knew their grammar and flaunted some idioms. However, this is a very positive indicator that they were as chatty as Homo sapiens, and that could change who and what can be classified as human.

3 Toys For Their Kids

Educational toys appeared to have been a thing in Neanderthal society. The discovery of what appear to be several toy axes is adding to a growing body of evidence that Neanderthal families existed as close groups in which members cared for each other. In this case, parents also created items to keep the youngsters entertained. Additionally, they likely even schooled their offspring in skills they would one day need as adults.

European Neanderthal sites, two of them in England, delivered the small and toy-resembling tools. It is easy to see why many believe that the artifacts were, in fact, playthings. A grown Neanderthal would not have been successful performing any task with such a reduced tool.

In France and Belgium, sites were discovered where stone tools were created. Some of the rocks were expertly worked, but alongside those were stones that showed an inexperienced hand. Researchers are considering the possibility that Neanderthal kids were being taught the techniques of toolmaking by the older members of the community.

2 The Boat Question

A certain type of stone tools, called “mousterian” tools, is unique to Neanderthals. This is how scholars knew that they once visited several islands in the Mediterranean Sea. However, some of these islands were so far outside of their normal range that swimming wasn’t an option. One such island was Crete. To get there from mainland Greece would have meant crossing 40 kilometers (25 mi) of ocean. The swimming theory sinks particularly fast here. The first person would have been forced to paddle out into the great blue ocean without even knowing about Crete’s existence. So, how did Neanderthals get there?

Remarkably, several experts and institutes are starting to consider that Neanderthals were seafarers. Finding their trademark tools on a far-flung island fits if boatbuilding and traveling are added to their growing repertoire of skills. The Crete artifacts are around 100,000 years old. The oldest seafaring evidence for modern humans dates to 50,000 years ago. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Neanderthals sailed an extra 50,000 years before humans caught on. Since all boats would have been wood, any solid traces of who set to sea first decayed a long time ago.

1 They Cared For The Disabled

One Neanderthal burial unfortunately lead to the misconception that every member of his kind was hunch-backed and stupid. When a Neanderthal was found in 1908 in Southern France, his spine was bowed. For some reason, this became the popular image for Neanderthals.

A 2013 study revealed that the man was elderly (aged 30–40) and severely handicapped. In life, he was barely capable of walking. Several of his vertebra were fused or broken, and his right hip was abnormal. He had no teeth to chew food with. Without family or community care, this individual would not have lived for so long.

When he passed away around 50,000 years ago, nobody tossed him out as carrion. He was respectfully buried in a cave. The grave was carved into the stone floor, and earth was tightly packed around the body. Creating the pit and filling it up took a long time, but it was apparently done with willingness and empathy. The effort implies that the local Neanderthals developed a tradition of holding funerals for lost loved ones.