Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Top 10 Disgusting And Unexpected Medical Treatments

Even before the outbreak of Covid-19, the image of modern medicine in developed countries has for some time been one of ruthless cleanliness and clinical dazzle. But for most of history, medicine was often raw, messy, and outrightly disgusting. In contexts where plague, smallpox and cholera were the norm, not the exception, patients were rarely squeamish. Nature was frequently trying to kill you; and the response of doctors and patients was to try to get nature on their side. And three or four hundred years ago, what would later be derided as popular magic was often advocated by some of the best educated men in Europe.

10 Suppressed Alternative Medical Treatments

10 The Wound Salve

One of the very strangest treatments of the early modern era was an ointment which would be smeared not on your wound, but on the implement which had wounded you. This form of ‘sympathetic magic’ was advocated by men such as Walter Ralegh and Kenelm Digby, an important proto-scientist of the 17th century. The influential Belgian chemist Jean Baptiste van Helmont recommended making the salve with ‘the moss of an unburied cranium; the fat of man, each two ounces; mummy, human blood each half an ounce’, and ‘oil of linseed, and turpentine, each one ounce’.

A variation discussed by Francis Bacon required ‘the fat of two bears, killed in the act of generation’. Yes, really. You not only had to sneak up on two amorous bears, but judge from their ursine growlings and swoonings the exact moment when mutual orgasm (then thought essential to conception) was occurring. And then shoot them. The Wound Salve may have worked in some cases, simply because surgeons did not touch the patient and transmit germs and possibly fatal infection to the wound.

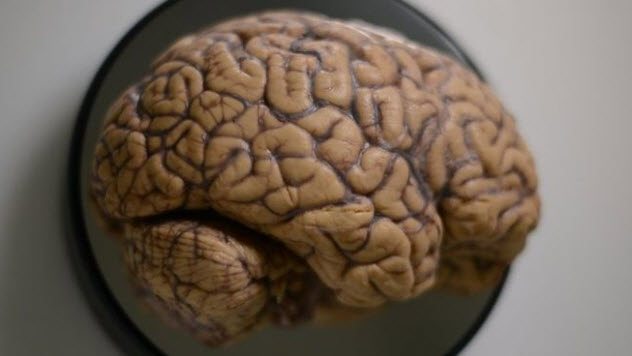

9 Cerebral Pâté

This treatment for epilepsy was prescribed by John French, a 17th century chemist and doctor friendly with the Father of Chemistry, Robert Boyle. The practitioner should ‘take the brains of a young man that hath died a violent death, together with the membranes, arteries, veins, nerves, [and] all the pith of the back’, and ‘bruise these in a stone mortar til they become a kind of pap’. Over this cerebral pâté you should then pour ‘as much of the spirit of wine, as will cover it three or four fingers breadth’, convey the whole into a large glass, and allow it to ‘digest … half a year in horse dung’ before distillation.

French was a keen anatomist, and dissections were carried out at the Savoy Hospital where he worked. He would therefore have had little trouble obtaining fresh human heads and similar ingredients. In 2011 Tony Robinson and I had the interesting task of making up French’s medicine for television, using free-range pig. We learned a lot. Although it had sounded to me like cerebral pâté, in reality, it was much more like soup. But we did skip the half a year in horse dung.

8 The Homunculus

In 1650, A New Light of Alchemy contained the following recipe. ‘Let the sperm of a man by itself be putrefied in a gourd glass, sealed up, with the highest degree of putrefaction in horse dung, for the space of forty days, or so long until it begin to be alive, move, and stir, which may easily be seen. After this time it will be something like a man, yet transparent, and without a body. Now after this, if it be every day warily, and prudently nourished and fed with the arcanum of man’s blood, and be for the space of forty weeks kept in a constant, equal heat of horse-dung, it will become a true, and living infant.’

So said Paracelsus, the great medical iconoclast of the early 16th century – adding: ‘this we call Homunculus, or Artificial [Man]. And this is afterwards to be brought up with as great care, and diligence as any other infant, until it come to riper years of understanding.’ Though Paracelsus died in 1541, some of the most daring scientists of the 17th century seem to have taken the homunculus seriously – confirming that their unofficial theme tune should have been The Doors’ song, ‘Break on Through to the Other Side’.

7 Skull Smoothie

In the 1660s, one English doctor was recommending for apoplexy a chocolate mixture which was also rich in calcium. It contained ‘the powder of the root of the male peony’ mixed with human skull, ambergris and musk. To this one should add ‘of the kernels of the cocoa nuts one pound’, and ‘of sugar what will suffice’; and ‘of this make chocolate’, taking ‘half an ounce or six drams every morning in a draught of the decoction of sage or of the flowers of peony’.

The doctor in question was Thomas Willis. Now known as the Father of Neuroscience, in his lifetime he became the richest doctor in all England, buying up the 3,000 acre country estate of the Duke of Buckinghamshire. By this time, doctors had been enthusiastically prescribing chocolate for patients who could afford this novelty for some decades. It was especially recommended to women, on the basis that it would ‘make them fat and comely’.

6 Chicken and Pigeon Therapy

Amongst a myriad of imaginative and futile cures for plague, chicken therapy was particularly memorable. Plucking feathers from a live chicken, you held the bare part to your plague sore until the bird died – presumably of shock. You then used another live bird (and possibly a third) until you reached one which survived. This bird’s deliverance indicated that the plague spirits had been fully drawn out of you. Pigeons were also popular. When one of Webster’s characters in The Duchess of Malfi stated, “I would sooner eat a dead pigeon, taken from the souls of the feet of one sick of the plague, than kiss one of you fasting” audiences would have known what he was talking about.

The broad logic of this was supported by some of the most élite doctors of the day. When John Donne fell dangerously ill in 1623, he had the king’s own physicians sent to his sickbed, and dead pigeons were placed at his head to draw out malign vapours. In 1656, Christopher Irvine, royal surgeon and brother of a baronet, stated that ‘the arse of a hen plucked bare, and applied to the biting of a viper, freeth the body from venom’. Various of these pigeon cures were being used in popular medicine throughout the nineteenth century.

5 Aqua Divina

This ‘divine water’ may have looked quite attractive. But, if you are ever offered any of this pleasant-sounding drink, you should bear in mind that a Paracelsian chemist would have prepared it by taking ‘a whole carcass with the bone, flesh, bowels (of one killed by a violent death)’ cutting it into very small pieces, and mashing it up until the whole pulverised mass was indistinguishable.

Fortunately, it seems that few patients actually drank Aqua Divina. The corpse pâté was then distilled into liquid, and used to take disease away from a patient, by mixing some of the patient’s blood with it. One of the biggest advocates of this recipe was an influential German chemist, Johann Schroeder. Although Schroeder died in 1664, his cures were still keenly recommended in 1739 by an Irish priest, John Keogh. Keogh’s patients were doubtless reassured not just by his piety, but by his marriage to a cousin of the Duchess of Marlborough.

4 Poison

Along with a bewildering number of medicines prepared from human corpses, there were also several guides to distilling fabulous poisons from human bodies. To make matters worse, the bodies in question were often live ones. One account of 1638 told of how a red-headed sailor was abducted in North Africa, and presently found hung upside down, with his back broken, and his face and throat swollen. He had supposedly had vipers forced into his mouth – after which he was ‘hung up and exposed unto the hot sun, with a silver basin under his mouth’. The liquid received here ‘made a kind of poison so deadly, that it did surely kill where it touched’.

Another story related how a cardinal used his mistress to make poison (this being essential to the everyday life of a busy Catholic priest in early-modern Italy). He buried her up to her waist in a hidden courtyard, and then applied vipers to her breasts, from which he could presently milk a fabulous poison for his priestly duties.

3 Patients? I piss on them!

The Italian doctor Leonardo Fioravanti was working in Africa in 1580 when a Spanish gentleman, Andreas Gutiero, began arguing with a soldier. Seeing Gutiero draw his weapon, the soldier quickly struck a left-handed blow with his own sword ‘and cut off Gutiero’s nose’. When this ‘fell down in the sand’ Fioravanti picked it up ‘and pissed thereon to wash away the sand’ before stitching it on again and dressing it with his ‘balsamo artificiato’. After being bound up for eight days, the nose was found ‘fast conglutinated’ and Gutiero made a complete recovery.

Given that it is sterile when it leaves the body, urine was probably safer than the kind of water generally available. As Mary Beith points out, the chemical urea is still used in modern medicine in ‘treatments for ulcers and infected wounds’. Urine had been used against wounds by Henry VIII’s surgeon, Thomas Vicary (d.1561), whilst our Restoration doctor Thomas Willis would advise some of his patients to drink their own.

2 Borrowed Arm

In 1597 the Italian surgeon Gaspare Tagliacozzi published a description of the technique he used for reconstructing a damaged or missing nose. A skin flap was cut from the patient’s own arm and stitched onto the missing or damaged nose. Although stitches could be removed after a week, the patient had their nose splinted against the arm for up to three weeks. If this sounds less than ideal, well – imagine having your nose splinted against someone else’s arm for three weeks…

For the story goes that Tagliacozzi handled a case in which an Italian nobleman paid his servant to donate some of his arm for the Master’s new nose. After these interesting three weeks as Siamese twins (toilet break, anyone?) the servant gained his complete freedom and went to live in Naples, the nobleman remaining in Bologna. The operation seemed to have been a success. But presently the nose began to rot. Why? Well, allegedly because the servant had in fact died, and the nose retained a ‘secret sympathy’ with its host body. Deemed sacreligious for his attempts to improve on God’s work, Tagliacozzi after death had his corpse exhumed and cast out of holy ground – not, in this case, by the superstitious masses, but by the holy and humble Catholic Church itself.

1 Cutting for the stone

Upon his death in 1622, the Puritan minister Nicholas Byfield underwent an autopsy which yielded a bladder stone of thirty three ounces in weight (compare a good-sized red cabbage). After Samuel Pepys was successfully cut for the stone on 26 March 1658, he kept as a memento an object ‘as big as a tennis ball’. In May 1669 the brother of fellow diarist John Evelyn seems to have been suffering from a bladder stone for some time. Because he was resistant to the idea of an operation, Evelyn took Pepys along in an effort to persuade the afflicted brother.

We can well imagine that Evelyn did not tell his brother about the lithotomies which he had seen in a Paris hospital in 1650. ‘There was one person of forty years old had a stone taken out of him, bigger than a turkey’s egg: the manner thus: the sick creature was stripped to his shirt, and bound arms and thighs to an high chair, two men holding his shoulders fast down: then the surgeon … made incision through the scrotum about an inch in length … then with another instrument like a crane’s neck he pulled it out with incredible torture to the patient’. Evelyn saw another patient showing ‘much cheerfulness’ and ‘going through the operation with extraordinary patience, and expressing great joy, when he saw the stone was drawn’. This subject was a child, just eight or nine years old.

![Top 10 Disgusting Foods The Chinese Eat [DISTURBING] Top 10 Disgusting Foods The Chinese Eat [DISTURBING]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/23773182-0-image-a-46_1580303417295-150x150.jpg)