Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Weird Things Found at the Bottom of the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, inhabiting over 152,800 square kilometers (95,000 square miles) and filled with 27.3 quadrillion liters (6 quadrillion gallons) of water (no, really!), collectively make up the largest body of fresh water on earth. More than 170 species of fish (and perhaps one Loch-Ness-like creature) lurk beneath the surface, and its waters have claimed over 6,000 ships.

But sunken vessels aren’t the only thing hanging out on the lakes’ sandy floors. Check out this list of truly weird things that can be found at the bottom of the Great Lakes.

Related: 10 Intriguing Discoveries In Lakes

10 A 1910 Locomotive Steam Engine

In June 1910, a rockslide derailed Canadian Pacific Railroad locomotive 694 as it traveled along Lake Superior’s sea cliffs just outside of Marathon, Ontario. Three men lost their lives when the engine, several boxcars, and a tender car crashed into the pile of rocks and then toppled into Lake Superior’s waters, settling at a depth of 18.3 meters (60 feet).

The wreckage rested there for 106 years, until shipwreck hunters located it in 2016. It is the Great Lakes’ only known locomotive wreck.[1]

9 The Largest Unmodified Collection of Nash Automobiles in the World

Why are they “unmodified”? Well, they’re nearly 500 feet underwater, for starters, which makes it a little hard to add those dope suspension upgrades.

On October 31, 1929, the SS Senator left Milwaukee, headed to Detroit with 268 Nash Automobiles valued at $251,000 (over $3.8 million in 2020 dollars). In a murky fog, she was rammed by another ship, sinking in 8just eight minutes. As the ship came to its final resting place 131 meters (430 feet) below the surface of Lake Michigan, seven members of her 28-man crew perished in the icy waters.

The shipwreck was located in 2005 using a side sonar scanner. It was noted that the cars originally chained on deck were lying crumpled on their sides, but the vehicles housed within the steamer were perfectly preserved. While no historical documentation exists to indicate if the vessel carried 1929 or 1930 models, it is accepted to be the largest collection of unmodified Nash vehicles in existence. In 2016, the site of the wreckage was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[2]

8 Michigan’s Very Own Stonehenge

While using sonar equipment to locate shipwrecks in 2007, underwater archaeologists identified a circular formation of stones 40 feet deep beneath Lake Michigan. Dubbed a “miniature Stonehenge” by local media, the 1.25-meter (4-foot) tall rocks make it a bit shorter than the iconic megalith, but they’re equally as mysterious in their origins.

The formation is thought to have been assembled by the area’s Indigenous people, likely created during the last Ice Age when the lakebed was dry. One of the rocks features a possible hieroglyph of a mastodon, a hairy beast estimated to have gone extinct in the area about ten thousand years ago. Verifying its authenticity will help confirm the age of the Stonehenge-like formation.

For the moment, the purpose of the rocks remains a mystery, though a similar formation has been located on Beaver Island, a bit north of this location and on dry land. The existence of this second formation is a good indication that the stones aren’t a random accident.[3]

7 An Ancient Hunting Camp

An arrangement of rocks, thought to be built for hunting, was found in Lake Huron at a depth of about 36.5 meters (120 feet) along the Alpena-Amberley Ridge that extends from Northeast Michigan to Southern Ontario. Nine thousand years ago, lake levels were approximately 76.2 meters (250 feet) less than what they are today, and archaeologists hypothesize that the ridge, with water on both sides, allowed hunters of migrating caribou a distinct advantage over their prey.

Using a remotely operated vehicle and sonar, scientists discovered two parallel lines of stones along the ridge that dead-ended in a way that would have allowed the hunters to trap the animals. Scattered along the path were additional V-shaped stone formations, thought to be hunting blinds. Divers at the site also discovered artifacts that native peoples might have used to sharpen and repair their hunting tools.[4]

6 Rare World War II Fighter Planes

The Douglas Dauntless World War II fighter plane was rumored to take two hundred bullets and still see her pilot safely home. Few of them were spared from seeing a day in battle, and today only 14 known planes remain of the nearly 6,000 built between 1939 and 1944.

There are, however, about 75 of them sitting on the bottom of Lake Michigan.

Deciding the lake was far enough inland to be safe from attack, the U.S. Navy began training World War II carrier pilots there starting in 1942. It launched its first aircraft from the USS Wolverine, which, at 167 meters (550 feet) long, was shorter than the average aircraft carrier. It was thought that if a pilot could land on that shorter deck, he could land on any deck in the U.S. Navy.

Overall, the training program was a huge success, with 35,000 new pilots making more than 120,000 successful landings. But there were “misses” as well. U.S. Navy records show 128 losses and over 200 “accidents.” Most resulted in only minor injuries, and the Douglas Dauntless aircraft weren’t salvaged for repair unless they sunk in shallow water.

Efforts to recover the aircraft started in May 2004, and today several of those 14 existing planes are pieces of the collection found in Lake Michigan.[5]

5 A World War I German U-Boat

In 1921, the U.S. Navy gunboat USS Wilmette fired eighteen 4-inch rounds at a German UC-97 submarine in the middle of Lake Michigan. Thirteen of the eighteen rounds struck the vessel, and it sunk in 200 feet of water.

More interesting, though, is what was a German U-Boat doing in Lake Michigan, to begin with?

German submarines were responsible for the sinking of dozens of Allied shipping and war vessels. When the war ended, the British seized the German navy, including 176 U-Boats. They allowed Allied nations to each take a few and study their adversary’s technology.

The United States took six boats. In addition to examining the technology, the U.S. opted to “tour” the boats to various ports, allowing the curious public to see the vessels that orchestrated so much wartime carnage. A UC-97 was sailed up the St. Lawrence Seaway and became the first submarine to ever enter the Great Lakes. Tourists in various ports paid a modest fee to see the boat, which was applied to the U.S. war debt. When the tour was complete, it was towed out to the middle of Lake Michigan, where the U.S. Navy training ship USS Wilmette used it as target practice, sinking it per the requirements of the Treaty of Versailles.

Attempts to find the sunken U-Boat were underway as early as the 1960s, but the sunken wreckage wasn’t located again until 1992.[6]

4 An 11-Foot Marble Crucifix

Unlike many other items on this list, the Italian-made marble crucifix ended up in Lake Michigan, 244 meters (800 feet) off the shore in Petoskey, Michigan, quite on purpose.

Commissioned by a Michigan couple as a grave marker in the 1950s, the statue was carved in Italy and features a traditional, life-sized depiction of a 1.67-meter (5-foot-5-inch) Jesus on a cross that stands at 3.35 meters (11-feet) total. Unfortunately, it suffered a crack when shipped overseas. The couple ultimately rejected it, and it was sold at an insurance sale.

The Wyandotte Diving Club purchased it to commemorate a diver who’d died doing what he loved. The statue was positioned about 365 meters (1,200 feet) offshore in Lake Michigan, where divers could enjoy it and pay their respects.

In the early 1980s, the Michigan Skindiving Council began a salvage and restoration process, moving it closer to shore and adding a new base. The president of the Little Traverse Bay Dive Club suggested a winter viewing of the memorial, now sitting at a depth of about 6.5 meters (21 feet). He provided some underwater lighting, and now, when icy conditions permit, visitors walk out to view it through a hole in the ice.[7]

3 Old Whitey, the Preserved Corpse of the USS Kamloops

The Great Lakes, at their depths, stay at a temperature of about 4°C (40°F), and its clear, sterile waters are perfect for keeping sunken items well preserved. This includes all the bodies of sailors who went down with their ships.

When the cargo vessel USS Kamloops sunk in Lake Superior in December 1927, it remained lost for fifty years. Upon its rediscovery, divers found that the ship had been amazingly preserved in Superior’s cold, bacteria-free environs. Lifesavers candy was found still in its packaging. Shoes, furniture, and fixtures were found in near perfect condition, and faucets even still turned.

This was also true of the body they found in the engine room. Because of a natural process that occurs in cold temperatures after a human body dies, corpses take on a white, waxy appearance, which explains why divers have since nicknamed the engine room steward “Whitey.” He remains there, in his watery grave, waiting to greet others who explore his boat.

While Whitey is a notable Lake Superior corpse, he is one of many to have gone down with his ship on the Great Lakes. Many wrecks are controlled diving sites for this reason—families of the dead don’t want their loved ones disturbed in their final resting place.[8]

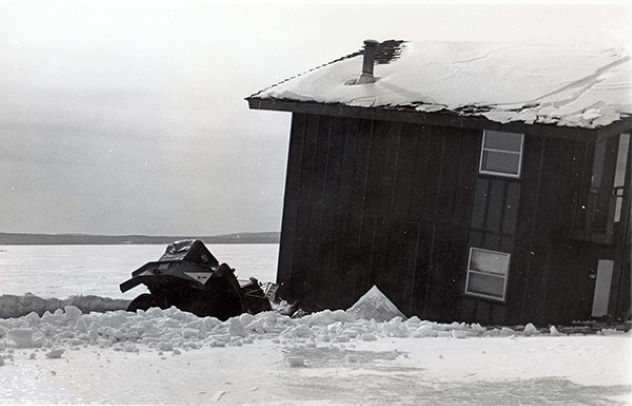

2 A Seven-Room, Fully Furnished Vacation House

The 6.5-kilometer (4-mile) path between Bayside, Wisconsin, and Madeline Island in Lake Superior was frozen over in the winter of 1977. But was it frozen enough to move a house across?

Lyle Rhine of Dale Movers in Minneapolis was convinced it was. He had an ice road explicitly plowed for the purpose of moving the house from the mainland to the island. On March 2, the four-mile ride commenced.

It progressed pretty well for the first three of those miles.

At the three-mile mark, the tires of the trailer holding the house broke through the ice. Lyle and his riding partner, who had been wisely driving with the doors of their vehicle open, bailed from the truck while it was still in gear. The truck sank first, and then the home, in 21 meters (70 feet) of water.[9]

The following summer, the Coast Guard insisted the owner salvage the wreckage, and the truck was brought to the surface. Cables were tied to the house in hopes of keeping it intact, but efforts to raise it were unsuccessful…it broke into pieces and remains on the lake’s floor.

1 Canadian Model Airplanes

Okay, these weren’t just any model airplanes. These 1/8-scale models were for a cutting-edge aircraft built by Avro Canada for the Royal Canadian Air Force…in the 1950s.

These models were flown over Lake Ontario as the plane was being developed, testing the “delta wing” design to confirm performance at Mach 1 and Mach 2 speeds. The Avro Arrow, as it was called, was the only supersonic interceptor ever built in Canada, constructed in response to Soviet long-range bombers that could conceivably attack North America by crossing the Arctic Circle.

Canada’s Prime Minister abruptly canceled the initiative in 1959. Six completed planes were scrapped, as well as nine of the models that tested aircraft performance at various milestones in its design. It’s been suggested that Soviet spies had infiltrated the development center, and efforts were made to destroy the technology so it could not be replicated.

Four of the nine models have been recovered from Lake Ontario’s sandy floor and are being restored by the Canadian Conservation Institute.[10]