Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Top 10 Chilling Facts About India’s “Skeleton Lake”

Nestled at the bottom of the steep slope of Trisul, one of the highest mountains in the Indian Himalayas, rests a small, remote body of water with a terrifying secret. Roopkund Lake—16,500 feet (5,029 meters) above sea level and less than 135 feet (41.1 meters) in diameter—is almost perpetually frozen. The shores and surrounding valleys are both blanketed with snow. Only the summer heat reveals its secret as the waters melt and hundreds of bones float to the surface. Human remains and ancient artifacts appear scattered upon its shores like a scene straight out of a horror film.

The disturbing nature of the site has earned it the nickname “Skeleton Lake” or “Lake of Skeletons.” The local government describes it as a “mystery lake” in tourist promotions. One thing is for sure: there is no other place like it on Earth. Explore this perplexing ancient mystery with ten chilling facts about Roopkund Lake.

Related: 10 Weird Things Found at the Bottom of the Great Lakes

10 A Gruesome Discovery

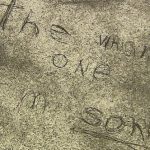

Ranger H.K Madwhal was the first to report the skeletons at Roopkund Lake in 1942 after he and his group stumbled upon them during a plant-hunting expedition. He described a “ghastly scene that made us catch our breath.” The cold temperatures preserved the remains so well that many bones still had some flesh and hair attached. The porters were so terrified by the sight “that they at once took to their heels, thinking that they had landed in a ghost land.”

Madhwal and his assistant took a closer look and noticed that some of the bodies were larger than was typical in the area. They also observed bamboo sticks, utensils, large leather sandals (chappals), and umbrellas sticking out of the snow. Unfortunately, an ongoing WWII delayed an official investigation. It wasn’t until 13 years later that researchers discovered the lake and its shores held the skeletons of as many as 800 people.[1]

9 Local Mythology of Roopkund Lake

Locals tell two versions of an ancient myth about the formation of Roopkund Lake and Trisul Mountain. In the first version, Mahadeva (Shiva), “the supreme or great being,” sought a water source for his thirsty consort, Nanda Devi. He struck his trident to the ground and forged the Trisul (meaning “trident”) mountain and two lakes.

While Nanda Devi, meaning “bliss-giving goddess,” was drinking from one of the lakes, she caught a glimpse of her reflection in the water for the first time. That initial glimpse of her “beauty” or image inspired its name. Roopkund means “reflection lake” or “beauty lake.” The second version of the legend claims Nanda Devi was the one to strike the ground with the trident instead of Mahadeva.

Nanda Devi is the most revered goddess in the Garhwal region of Uttarakhand, where the goddess mythology saturates the lives of the residents. Many deeply respect the Nanda Devi mountains, located northeast of Roopkund Lake, which are part of the Nanda Devi National Park and Biosphere. The entire region is considered sacred, with many shrines spread throughout.[2]

8 Rat Jat Pilgrimages

Pilgrimages honoring the goddess Nanda Devi, known as “Rat Jat,” have been held every 12 years for centuries. People from around the world gather together to take part in this special pilgrimage. Over 50,000 people participate in Rat Jat, even though not everyone is allowed to go to the final destination: Homkund Lake.

“The rules stated that music, children, women, elderly folks, leather goods, the lower castes were strictly prohibited from proceeding beyond Wan.” (Wan is about three or four days before Roopkund on the trail).

Homkund Lake, encircled by the Trisul and Nanda Ghunti mountains, is said to be the dwelling place of the gods and is thought to be where Nanda Devi’s palanquin was housed. Symbolically, the pilgrimage allows participants to escort Nanda Devi on her way home. The trek is 175 miles (281.6 kilometers) and takes about 22 days to complete. A good portion of the pilgrimage is with bare feet. The last Rat Jat pilgrimage was in 2014.[3]

7 A Popular Folk Song about the Goddess Nanda Devi

Some suggest that a popular folk song about the goddess Nanda Devi could help shed some light on the victims’ mysterious deaths. The song describes a royal procession during a Rat Jat pilgrimage, where a king, his pregnant queen, and their entourage enrage Nanda Devi by defiling the holy landscape with dancing girls. As punishment, Nanda Devi turned the dancers to stone before striking the rest of “the group down with ‘iron balls’ thrown from the sky.”

The song inspired a theory that the victims got caught in a severe hailstorm. Researchers tested this and other scenarios and found that some individuals’ skulls had unhealed fractures that could have come from hailstones. “The only plausible explanation for so many people sustaining such similar injuries at the same time is something that fell from the sky,” said one researcher at the time, suggesting the hailstones would have been as large as 9 inches (22.9 centimeters) in diameter.

Based on the topography and elevation of Roopkund Lake, it’s not out of the question. The area is known to experience sudden and violent storms, and it offers no place for shelter.[4]

6 Disturbances by People and Environmental Factors

When Ranger Madhwal first made the ghastly discovery, whole skeletons were visible on the surface of Roopkund Lake. But researchers saw only pieces when they first began studying the site in 1955. While there, they witnessed large rocks rolling down the mountainside and crashing into the water. They quickly deduced that these falling rocks, combined with avalanches and earthquakes over the years, were responsible for breaking most of the remains.

The area is prone to landslides as well. Some have suggested that these could have easily moved skeleton bones down the mountain and into the cold waters below. In addition to the various disruptive environmental factors affecting the site, local pilgrims and hikers regularly visit the area. Some have handled the skeletons and removed artifacts.[5]

5 There Were at Least Two Different Groups

In the early 2000s, preliminary DNA testing established that the people who died at Roopkund Lake were of South Asian ancestry. Radiocarbon testing dated the bones around the site cluster at 800 AD suggesting they all died in a one-time mass event. But a 5-year-long study published in Nature Communications in 2019 shocked everyone by disproving that story.

Twenty co-authors from 16 institutions based in India, the U.S., and Germany successfully tested 38 sets of skeletal remains, including 15 women. They found that most of the victims were tall, or “more than average stature,” but some were “very robust and tall” while others were “long and lanky.” Tests also determined that most were middle-aged, between 35 and 40 years old, and that none of the victims were related to each other.

Twenty-three of the victims were of South Asian ancestry, as researchers had initially suspected, but the study found that they died during two or more events rather than a one-time mass event. The remaining 14 victims died a thousand years later than the South Asian group. Researchers currently believe this group died in a single event.[6]

4 A Long Way from Home

There was one other notable difference between the two groups of victims at Roopkund Lake. Researchers were stunned to find that the genetic ancestry of the 14 victims was tied to the Mediterranean, more specifically, Greece and Crete. (There was also one individual in the group who was of East Asian ancestry.). What the Mediterranean group was doing at Roopkund Lake, over 4,500 miles (7,242 kilometers) from home, has been speculated ever since. One popular theory was that the victims were part of an army or a group of merchants. However, no weapons have ever been discovered in or near the lake, nor is it located near a trade route.

“It is still not clear what brought these individuals to Roopkund Lake or how they died,” said senior co-author Niraj Rai, an archaeogeneticist at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences in Lucknow, India, in a press release. “We hope that this study represents the first of many analyses of this mysterious site.”

While the new study has raised more questions, Rai and his co-authors are grateful that the analysis has put some theories about what killed the victims to rest.[7]

3 Victims of a Pandemic or a Pilgrimage Gone Wrong

In 2004, a National Geographic documentary suggested the skeletons were the victims of a pandemic laid to rest in the lake. But the theory proved false when researchers failed to find any trace of an ancient bacterial pathogen that would provide disease as a cause of death. (Though they noted that the DNA pathogen might have been too low a concentration to detect.) The victims were all shown to be reasonably healthy at the time of death.

Researchers found that the South Asian group died in at least two separate events between the 7th and 10th centuries, upending a long-held theory that it was a mass death. The group of Mediterraneans, on the other hand, is still believed to have perished in a one-time mass event that may have occurred during a pilgrimage event. The only problem is that the first credible accounts of Rat Jat pilgrimages do not appear until the late 19th century. However, some believe that inscriptions in local temples dating back to the 8th and 10th centuries might indicate earlier origins.[8]

2 Accidents and Suicides at the Lake

Some other theories involve a steep upper edge near Roopkund Lake known as the “Alley of Death.” Jyura Gali is a sheer ridge with an excellent view, but anyone who falls is doomed to join the other victims in Skeleton Lake. The pilgrimage was banned a few hundred years ago because there were so many accidental deaths from the Gali. But the ban was lifted sometime later.

There is also a belief that many pilgrims used Roopkund Lake for self-sacrifice. Inscriptions at stops and shrines along the pilgrimage trail describe the intentions of some pilgrims to take their own lives there. According to R.S. Negri, a scientist and researcher, there were so many cases of these suicides, known as Atmosarg, that the government banned them in 1931.[9]

1 There Are Still Only Theories

No one knows what brought the Mediterranean group to Roopkund Lake or how they died there. But researchers claim their presence suggests that the area was not just popular with the locals but attracted visitors from around the world. Studies of the victims and artifacts continue, though it is unclear whether they will provide answers or more questions.

Research may even reveal that the group died off-site. Kathleen Morrison, the chair of the anthropology department at the University of Pennsylvania, told the Atlantic that it is unlikely that all victims died at the lake. “I suspect that they’re aggregated there, that local people put them in the lake. When you see a lot of human skeletons, usually it’s a graveyard.”[10]