Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

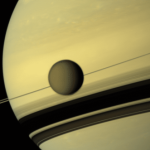

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Surprising Secrets of Notre Dame Cathedral

On December 8, 2024, the venerable cathedral of Notre Dame will reopen its doors to the public, fully restored and recovered from the terrible fire of 2019. Too late, perhaps, for the 2024 Paris Olympics, but an event millions still look forward to. It’s a celebration of the resilience of an eight-century-old structure.

The construction of Notre Dame took two centuries to complete. It was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site and was visited by millions of tourists annuałly before the fire, and will welcome millions more in the future. They will see not only marvelous architecture and engineering but also soak in an atmosphere steeped in tumultuous history and intriguing secrets. In this list, we delve into some of these stories that will make your visit to Notre Dame, should you decide to go, a more interesting adventure.

Related: 10 Unusual Religious Buildings from around the World

10 The Middle Eastern Connection

Gothic architecture is considered uniquely European. Yet research seems to suggest more Middle Eastern influence than we think. For instance, the twin towers of Notre Dame have their prototype in a 5th-century Syrian church called Qalb Lozeh. The Frankish crusaders of the 12th century took the basic plan home with them, the seed of the Gothic style.

The Gothic pointed arch appears to have been borrowed from Islamic precedents, as it was used for the first time in the Ibn Tulun mosque in Cairo. Ribbed vaulting was inspired by the Abbasid palace of Ukhaider in Iraq, dating from the 8th century. The Umayyad palace of Khirbat Mafjar near Jericho inspired the Rose Window. The mosque of Damascus featured the first known spire.

Pointed arches, ribbed vaults, rose windows, and spires became classic elements of the Gothic. No wonder the great architect Sir Christopher Wren would rather call the style Saracenic (Arab Muslim) than Gothic.[1]

9 St. Etienne Cathedral

Notre Dame was built on Ile de la Cite in the middle of the Seine. It was not the first church on the spot, which had long been a political and religious hub due to its location at the crossroads of trade and commerce.

The Romans considered it a sacred site and erected a Temple of Jupiter in the very place the cathedral now stands. The remains of its sculpted altar were excavated in 1710 beneath the choir. When Christians took over the empire, they replaced the relics of paganism with their own edifices. A legend tells of an angel appearing to the emperor Charlemagne in a dream and instructing him to build a church on the island.

A church dedicated to St. Etienne (Stephen) was built on Ile de la Cite in the 4th century. It was consequently remodeled and enlarged to become a cathedral. Archeologists point to the square in front of Notre Dame as its location, having unearthed its column capitals and mosaics. A piece of St. Etienne was incorporated into Notre Dame itself, now known as the Portal of St. Anne.

In the 12th century, the bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully, was so impressed by the new pioneering Gothic Basilica of St. Denis that he decided to build his own. The rival church he envisioned superseding St. Etienne would be more magnificent and structurally daring. The first stone for Notre Dame was laid in 1165, but Sully would never see its completion. He died in 1196, 150 years before the last elements of his cathedral were laid.[2]

8 Sacred Geometry

Experts in semiotics (the study of signs) claim to see sacred significance in the measurements and architectural elements of Notre Dame, which became the pattern for later Gothic cathedrals. These symbols encode theological messages and motifs; indeed, the entire cathedral can be read like a text or likened to a hymn to God.

Seven is the divine number of perfection, and it recurs throughout the cathedral. The nave is divided into seven bays, horizontal and vertical, supported on each side by seven flying buttresses. The total number of bays is 153, the number of fish caught by the apostles, signifying the whole Church. The main level is 30 cubits high, as in Noah’s Ark, denoting a house protecting the people of God. The unity of Christ with the 12 apostles and the 12 tribes of Israel is seen in the 12 small chapels at the terminus of the apse and a main chapel in the middle.

The Vesica Piscis (literally, fish bladder) is a geometrical motif of two circles whose overlap traces the outline of a fish, a symbol of the union of God and man in Christ. Encoding the pi and Golden Ratio, the Vesica Piscis, combined with two pentagrams, determines the key intersection points in the cathedral’s overall floor plan.

The soaring verticality of Gothic cathedrals is meant to draw the eyes upward to heaven. The height of the nave is equally divided into three, the Trinity. On the church facade, the topmost points of the two portals flanking the main entrance connect to the center of the Rose Window, outlining a pyramid whose angle almost matches that of the Great Pyramid of Cheops. The overall effect, a pyramid with the Rose Window—the all-seeing eye of God—at the apex, reminds one that the Great Pyramid was considered the unifier of heaven and earth.

That Notre Dame was intended as a hymn to God—”music set in stone”—is deduced from the eight columns supporting the nave on each side. Eight is the number of notes in the tonal scale. Everywhere you look, inside or outside, Notre Dame’s stones are the lyrics to this silent hymn.[3]

7 Iron Staples

Reaching a gravity-defying height of 105 feet (32 meters), Notre Dame was the tallest building ever built in its time since the Great Pyramid. Thin walls support the vaulted ceiling as if by magic. Just how the light and elegant structure is held up was not completely understood—until the devastating fire of 2019 exposed the secret for all to see. Notre Dame was stapled together.

The fire uncovered the iron staples holding the stones together. Notre Dame was the first Gothic cathedral to use iron extensively as a building material. The thousands of iron staples are 8-20 inches (20-50 centimeters) long, weighing between 3 to 9 pounds (1.3 to 4 kilograms) each. Previously, builders used wooden tie rods stretched between the arches for support. Iron is more durable and easier to conceal, making Notre Dame’s dizzying height seem miraculous. It was a vast improvement in structural integrity.

Greeks and Romans used iron staples in their buildings, but only to secure large stones on the lower floors. The builders of Notre Dame were the first to use iron comprehensively, systematically, and dynamically, using the staples throughout the structure. This innovative “iron skeleton” would be adopted by later great Gothic cathedrals like Beauvais, Chartres, and Bourges.[4]

6 The Devil’s Doors

The magnificent intricacy of the ironwork of Notre Dame’s main doors still amazes experts today. With the limited tools available to medieval metalsmiths, it is astounding how such a masterpiece came to be. If these doors can blow people’s minds today, imagine how absolutely floored Parisians were back in the 1300s.

The doors were the tour de force of a young metalworker named Biscornet. Eager to prove himself, he worked at his furnaces, forging the twisting, swirling shapes worthy of Paradise itself. After months of arduous labor, the work was finally installed on the main doors. The people couldn’t believe such a marvel was created by human hands.

Rumors swirled that Biscornet had made a pact with the Devil to accomplish it and take the glory. It didn’t help that his name translates into “two-horned” (bis = two + cornet = horn), with obvious demonic connotations. Some claimed to have visited Biscornet’s workshop to find the artist unconscious on the floor with the work magically finished in record time, its iron swirls eerily looking like 666. The priests of Notre Dame said the doors wouldn’t open until they were sprinkled with holy water.

Biscornet died shortly after, possibly due to stress or exhaustion from work and fending off the accusations. For Parisians, it merely confirmed what they suspected. The Devil had come to take away Biscornet’s soul as his part of the bargain. Despite its unholy reputation, the church chose to retain the ironwork, and today, tourists can still marvel at the masterpiece that may have led to an untimely death for a young, talented artist.[5]

5 The Philosopher’s Stone

In 1923, a curious book titled Le Mystere des Cathedrales (The Mystery of the Cathedrals) appeared in Paris and caused a stir in occult circles. Its author, only known as “Fulcanelli,” claimed that the secrets of alchemy are openly displayed on the walls of Notre Dame. Art historians now largely accept the idea that Notre Dame is an alchemical text in stone.

The roof of the North Tower is adorned with an image, not of Jesus, Mary, or any other saint but of an alchemist wearing his Phrygian “wizard hat,” identifying him as an initiate to Hermeticism. The cathedral’s main door, the Portal of the Last Judgment, is said to hold the key to the Philosopher’s Stone, the sought-after substance that transforms base metals into gold and is the elixir of life. The portal’s central column depicts a woman with a ladder of nine rungs, the “scala philosophorum,” representing the nine steps of alchemical labor.

Bas-reliefs depict the stages of the alchemical process. One bas-relief shows a man holding a shield with a caduceus, the staff carried by the messenger of the gods Hermes and hence the alchemical symbol for the element Mercury. In the hands of Hermes, the caduceus could raise the dead to life, the aim of alchemy’s quest.

Of the 12 sculpted apostles decorating the archway, one is pointing up to an angel who is, in turn, pointing her finger toward the Left Bank of the Seine. To the location of the Philosopher’s Stone, perhaps? An eagle in the central portal, representing the power to turn common metal into gold, points in the same direction as the angel. No one knows what these clues mean, but placing these hidden messages at the very entrance shows that the builders considered alchemy of great importance.[6]

4 The Ghosts on the Roof

As can be expected of any old building, there have been many spooky stories that claim Notre Dame is haunted. There is the legend of a phantom bellringer who appeared on Christmas, the seven decapitated men looking for their heads near the cathedral one stormy night, and even the spirit of the damned Biscornet sitting in front of his cursed doors.

The most frequent ghostly visitors are two unknown women seen flitting on the roof among the stone gargoyles. The story goes that one October day in 1882, a young woman requested to go up the tower. The guard refused, as she didn’t have a chaperone as was required of ladies back then. Disappointed, the girl turned back and, walking along, met an elderly woman who was also touring the church.

The girl struck up an acquaintance with the woman and, warming to each other, had breakfast together, after which they returned to Notre Dame. Now, with the requisite companion, the girl asked to visit the tower again. This time, she and her friend were let in, and they toured the upper parapets until it rained.

The elderly lady took shelter in the bellringer’s room, leaving the girl outside. Moments later, witnesses heard a horrible scream. The girl had apparently jumped to her death, landing on the spiked railings below, and was nearly severed in half.

No one has ever identified the girl. The only clue was a handkerchief on her person monogrammed “M.J.” The elderly lady had also vanished and was never seen again—at least as flesh and blood. Her ghost, though, and that of M.J., had apparently decided to continue their rooftop tour for eternity.[7]

3 The Headless Statues

Under the balustrade of the West Facade (the front of the church, above the main doors), there is a horizontal band containing 28 figures representing the kings of Judah called the Gallery of Kings. During the Revolution, zealous mobs looking for symbols of royalty to destroy mistook the images to be those of French kings. They smashed the heads off the limestone sculptures and carried them away, presumably to ditch them into the Seine.

Instead, the heads were piled onto a nearby street and forgotten for three years until a wealthy lawyer took them to be used as part of the foundations of the mansion he was building. Thus buried, the heads were forgotten again, this time for 181 years. But in 1977, workers enlarging the basement of the French Bank of Foreign Trade unearthed 21 of the heads. By a fortunate coincidence, the bank’s president, Francois Giscard d’Estaing, the cousin of the French President, was an archaeology enthusiast and immediately recognized the value of the find.

Turning to the experts, d’Estaing was confirmed in his suspicions—these were the missing heads of the kings of Judah. And closer examination of the heads yielded another secret. Traces of polychromy meant that these statues, perhaps the entire Notre Dame, were once painted.

Of course, Notre Dame’s original colors would have been discreet, accentuating the regularity of the masonry. The colors chosen would have depended on the kind of stone used, as was customary for Gothic cathedrals. Chartres, for example, used yellow on light limestone; in Strasbourg, it was red ochre on red sandstone. Even then, we are so used to seeing Notre Dame in monochrome that simply imagining the cathedral in more vibrant hues staggers the mind.

As for the heads, they were taken to Cluny Museum, not far from Notre Dame, where they are now on display.[8]

2 Signed, Viollet le Duc

Along with the monarchy, the rich and powerful Catholic Church came under attack during the French Revolution. As a symbol of the detested religion, Notre Dame became a target for destruction by frenzied mobs. The church was badly damaged, and for a time, it was used as a warehouse. Then, it became a Temple of Reason for the state cult of the Supreme Being, which was intended to supplant Catholicism.

By the early 19th century, Notre Dame was in a pitiful state of neglect and disrepair. There was talk of demolishing it altogether. Author Victor Hugo, a lover of Gothic art, sought to turn people’s attention to the cathedral and preserve its treasures. He wrote a novel where the central character is not a human but a building he imbued with sentience, a quiet observer to the story of the bellringer Quasimodo and the gypsy Esmeralda. The Hunchback of Notre Dame came out in 1831, jolting people into realizing that they had abandoned a cultural treasure.

Parisian authorities chose the young architect Eugene Viollet le Duc to undertake the restoration job. He began work in 1844 and made his own additions to the structure: the 56 chimera or grotesques near the tower and the 750-ton spire, a casualty of the 2019 fire, were le Duc’s and not original to the medieval structure. He “signed” his work in a most peculiar way—he made the statue of the apostle Thomas up on the roof and a restored head on the Gallery of Kings to look like himself.

The restoration was completed in 1864. Notre Dame was saved. But its troubles were not yet over. Another attempt to destroy it was soon to come.[9]

1 The Heroes of Hotel Dieu

In 1871, a year after Napoleon III’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second French Empire, Paris was engulfed in a rebellion by the anti-royal and anti-Church Communards. The Paris Commune detested the conservative majority in the government, which they feared would restore the monarchy.

From March to May, Paris was a city under siege. Barricades, cannon fire, arson, and massacre were the order of the day. The revolutionists had already murdered the Archbishop and destroyed the Tuileries Palace, Palais d’Orsay, the Richelieu library at the Louvre, and many other landmarks and left large sections of Paris gutted. It was, therefore, some cause for concern when M. Hanot, the house surgeon of Hotel Dieu hospital next door to Notre Dame, heard a commotion outside while on duty at 3 a.m. on May 24.

Investigating, Hanot saw casks being rolled through a nearby barricade to the area between the hospital and the cathedral. Hanot suspected something sinister was afoot. Notre Dame had already escaped fire twice, the second time from petroleum shełls lobbed from the Palace Bastille. Were the revolutionaries about to finish the job?

Realizing that not only the cathedral would be destroyed but also the hospital, Hanot sent for the hospital director. By eleven that morning, smoke was already coming from one of Notre Dame’s windows. Hanot mobilized six other surgeons and some women and children who had collected outside. Going into the cathedral, they were forced back by the thick smoke. A firefighter offered his assistance, and the doctors were able to go in.

Burning braziers were found at the choir and high altar. Chairs, pews, and other combustible materials were piled all around, even as high as the great organ. The responders quickly doused the flames, and by nightfall, the area was secured by government troops. Notre Dame had been saved for the third time by the brave doctors of Hotel Dieu.[10]