Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

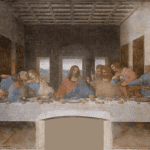

10 Common Misconceptions About the Renaissance

The Renaissance roughly spanned the 15th and 16th centuries and saw the revival of classical antiquity, with European scholars dedicating themselves to studying art and literature from Ancient Greece and Rome. It’s when William Shakespeare wrote his plays, Michelangelo painted the Sistine Chapel, and later thinkers like Isaac Newton continued the spirit of inquiry into the 17th century.

However, there are many misconceptions about the Renaissance—including the three iconic figures mentioned above, 10 of which are debunked below.

Related: 10 Bizarre Coincidences That Altered the Course of History

10 Newton’s Theory of Gravity from an Apple Falling on His Head

There is a seed of truth in the story that Isaac Newton was inspired to research gravity after being hit on the head with an apple while he was sitting under a tree. While an apple was most likely involved, there’s no evidence that the fruit hit Newton.

The polymath was spending the summer of 1666 at his family’s home, Woolsthorpe Manor, when he saw an apple fall from a tree and began wondering about gravity. He told a few people about this event in subsequent years. For instance, in his biography of Newton, William Stukeley recorded a conversation he had with Newton in 1726: “‘Why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground,’ thought he to himself: occasion’d by the fall of an apple, as he sat in a contemplative mood: ‘Why should it not go sideways, or upwards? but constantly to the earth’s centre?’”

Not a single account has the apple actually hitting Newton on the head.[1]

9 Queen Elizabeth I Rarely Bathed

It’s sometimes reported that Queen Elizabeth I once said she bathed once a month “whether she needed it or not” (although some reports give it as once a year). This led to the idea that people during the Renaissance were filthy because if the Queen boasted about bathing just once a month, her subjects must presumably clean themselves far less often.

There isn’t any reliable evidence to prove that Elizabeth uttered these words. And while full-body bathing might not have been as common during the Renaissance as it is now, there were plenty of other ways people ensured they were clean. While boiling water for a full bath was a lot of work (which the Queen would obviously delegate to her servants), washbasins and cloths were far more accessible and meant that people could keep fairly clean.[2]

8 Michelangelo Painted the Sistine Chapel on His Back

Between 1508 and 1512, Michelangelo painted a fresco on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican City. Given the location of the world-famous artwork, it’s often thought that Michelangelo completed the arduous task while lying flat on his back on a scaffold. This is how the painter, played by Charlton Heston, is depicted in the film The Agony and the Ecstasy (1965), but while the scaffold is accurate, the supine position is not.

The myth took off thanks to a translation error. In 1527, Paolo Giovio published a Latin biography of Michelangelo, describing him as being “resupinus” while painting. This word was often mistranslated as “on his back,” rather than what was actually meant: “bent backward.”

Michelangelo twisted himself into many uncomfortable positions while putting paintbrush to ceiling, some of which he described in a 1509 poem. “I’ve already grown a goiter from this torture, / hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy” and “My haunches are grinding into my guts, / my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight” are just a few examples that make it pretty clear that he wasn’t on his back.[3]

7 Galileo Invented the Telescope

It’s not unreasonable to think that Galileo invented the telescope—given that he’s known for his many important astronomical observations—but he actually only made his own device after hearing about other people’s inventions. The telescope was first invented in 1608 in the Netherlands, but who got there first isn’t certain, with Hans Lippershey, Zacharias Janssen, and Jacob Metius all independently designing one at around the same time.

In 1609, word of the “Danish perspective glass” reached Italy, and Galileo set about constructing his own device. His first design could magnify objects three times, but he eventually made an instrument that could magnify 30 times. Galileo wasn’t even the first person to use the instrument to study the sky though, with English astronomer Thomas Harriot noting down his observations of the Moon viewed through a telescope a month before Galileo did so.[4]

6 William Shakespeare Didn’t Write His Own Plays

The plays of William Shakespeare are some of the most renowned literary texts in history, but there’s a theory that Shakespeare wasn’t the author. Arguments range from Shakespeare not being well-educated enough to not being well-traveled enough to have written the plays.

Many different people have been suggested as the true author of the plays. Perhaps it was fellow playwright Christopher Marlowe, who may have faked his death and turned into Shakespeare? Or maybe it was Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, who didn’t want to sully his own name by writing plays for the common people? Or perhaps Shakespeare was a woman all along, with Mary Sidney being the top candidate.

However, the majority of Shakespearean experts agree that Shakespeare was the true author of his plays. Not only are there huge holes in the theories that other writers put forth, but all of the existing evidence—including contemporary documents and accounts—points toward Shakespeare as the author.[5]

5 The Americas Were Discovered by Christopher Columbus

In 1492, Italian explorer Christopher Columbus set sail for Asia under the Spanish flag and landed on the Bahamas (though he thought it was the East Indies). He’s often credited with being the first person to discover the Americas, but there were actually many people who reached the New World before him.

The first people who traveled to the Americas likely came from Russia around 16,000–35,000 years ago. Various waves of people made this journey over thousands of years, and these people became the indigenous American population. But taking Native Americans out of the picture, Columbus still wasn’t the first person to set foot in the Americas. Norse Vikings built a settlement in Canada’s Newfoundland around 1021, and Polynesian sailors may have landed in South America around 1,200.[6]

4 The Aztecs Thought Spanish Conquistadors Were Gods

It’s sometimes believed that when Hernán Cortés and his Spanish forces encountered the Aztec people in Mexico, they were mistaken for gods. The story goes that the Aztecs had a prophecy about a god called Quetzalcoatl who would return on a specific date. That date just so happened to be when Cortés arrived.

But the only evidence that the indigenous people believed this comes from Francisco López de Gómara’s Historia general de las Indias (1552). López de Gómara had never actually been to the Americas and was noting down Cortés’s experiences years after the fact. Neither Cortés nor any other contemporary source mentions the conquistadors being mistaken for gods. There’s also no evidence that the Aztecs had a legend about the returning Quetzalcoatl.

It wasn’t being awed by Cortés that led to the downfall of the Aztec empire. It was that the Spanish had more advanced technology—from armor and crossbows to horses and ships—and brought disease along with them.[7]

3 Niccolò Machiavelli Was Machiavellian

Given that the word Machiavellian—which means to be deceitful and cunning, particularly in political matters—comes from the name of Italian statesman Niccolò Machiavelli, it’s understandable that many people would think Machiavelli himself had those traits.

However, Machiavelli’s life and works are a little more complicated than that. His devious reputation comes from his book The Prince (1513), which—to simplify it—recommends that a monarch do anything they can to remain in power. Not only has this book generated wildly different interpretations—from a straightforward guidebook to a satire of princely power—but his other books are also far more in favor of republicanism. Whether this was due to a change of heart or proof that The Prince wasn’t to be taken seriously is debatable. Another possibility is that he wrote the book simply in an attempt to curry favor with the in-power Medici family—the book is dedicated to Lorenzo de’ Medici—because he had fallen from political grace.

Whatever the case, it’s at least an oversimplification to describe Machiavelli as Machiavellian, but it’s likely an outright falsehood.[8]

2 The Puritans Left England Because of Religious Persecution

It’s often said that the Puritans fled England because they were being persecuted for their religious beliefs. Certainly, religion in England was messy during the Renaissance, with many religious schisms popping up after King Henry VIII broke from papal authority. The invention of the printing press meant that people could now read the Bible independently.

But religious persecution isn’t why the Puritans left—the real reason was that the Church of England wasn’t Protestant enough for them. Having had their efforts to reform the church rebuked, they moved to Holland (now known as the Netherlands) in 1608. It wasn’t until 1620 that a group of Puritans—known as the Pilgrims—sailed to America from England aboard the Mayflower. But once again, they weren’t fleeing persecution.

Although the Dutch tolerated their religion better, they wanted to maintain the religious status quo. Not only that, but war was on the horizon. They thought America might offer better economic prospects and worried they would be assimilated into Dutch culture. Although America didn’t provide a blank slate for the Puritans—there were Native Americans already living there—they were better able to enforce their own religious beliefs.[9]

1 Johannes Gutenberg Invented the Printing Press

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press is one of the most important inventions in all of human history. Around 1440, he created a press that used movable type, allowing for the mass production of books. Before this, books had to be painstakingly handwritten. But while Gutenberg’s device revolutionized the written word, he wasn’t actually the first inventor of the printing press.

Efforts to create printing started as early as AD 800 in China, with people chiseling woodblocks with backwards letters that could then be inked and applied to paper. Although the blocks could be reused, the process of creating them was tedious. People attempted to make movable type out of wood and ceramic but failed.

Then in 1234, Korean civil minister Choe Yun-ui was asked to print a Buddhist text that was so long that it would have been too time consuming to create the individually carved woodblocks for each page. Choe decided to revisit the earlier attempts to make movable type, but this time he cast the characters in metal. These characters could be repeatedly rearranged in frames, inked, and pressed onto paper—essentially the same method that Gutenberg used many years later.

Whether Gutenberg developed his printing press independently or not is unknown, but the technology could have spread from Asia to Europe thanks to the far-reaching Mongol Empire. Either way, while Gutenberg wasn’t the first to come up with the printing press, he is the one who popularized it, making books more accessible than ever before.[10]