History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Intriguing Mysteries Of The Arctic

The Great White North is a forbidding and eerie place, which has spawned many fantastic stories and tales of folklore. Even in the real world, there are many historical and scientific mysteries about the frozen reaches beyond the Arctic Circle. As climate change starts to melt the ice, some mysteries may be solved, while others will remain forever obscured by the thaw.

10Levanevsky’s Flight

In 1937, the famed Soviet pilot Sigizmund Levanevsky took charge of what was intended to be the first cargo-passenger flight over the North Pole from Moscow to Fairbanks, Alaska. The distance was enormous, and experts thought that a full year of preparation would be needed. In a bid to impress Stalin, the officials in charge decided to do it in three months. The risks were so obvious that the aircraft’s radio officer even joked that the crew members were flying to their deaths. Unsurprisingly, something went wrong, and the man known to the American press as “the Russian Lindbergh” disappeared along with his six-man crew.

During takeoff, the far-right engine was clearly emitting smoke, but engineers on the ground predicted it would soon stop. Nineteen hours later, a radio message was received: “The far-right engine has quit due to a problem with the oil system. Entering overcast skies. Elevation 4,600 meters. Will attempt a landing.” Russian, Canadian, and American rescue teams combed the Arctic, but no trace of the aircraft could be found.

Over the years, there have been various theories about the final resting place of Levanevsky and his crew. The most plausible involves a radio operator from Point Barrow, Alaska, who was told local Inuit had witnessed an aircraft crash into the water near the Jones Islands. A visiting schooner attempted a search of the area, with the crew noting that their compass needle was pointing straight down at one point. However, no wreckage could be found and the search had to be called off due to ice. A report was sent to Moscow, but it was quickly forgotten about after World War II broke out.

Another theory suggests that there was a navigational error when the flight crossed the North Pole and was forced to descend below cloud level. Unbeknownst to the crew, they ended up making an accidental 80-degree turn, headed back into the Soviet Union, and crashed into Siberia’s Lake Sebyan-Kyuyel. A magnetic anomoly was apparently detected in the depths of the lake, but no more evidence could be found and the theory largely ran out of steam in the late ’90s.

Perhaps the most ridiculous theory is that Levanevsky was forced to land on an ice floe, where he was rescued by a German submarine. He then supposedly offered his services to the Luftwaffe, even participating in the bombing of Moscow.

9The Dorset Culture

The Paleo-Eskimos were among the first people to colonize the North American Arctic, long before the arrival of the ancestors of modern Inuit. For over 4,000 years, they lived in isolation from other peoples, gradually developing the Dorset culture of northern Canada and Greenland. But they quickly vanished after AD 1300, leaving little trace of their presence. DNA testing done on the hair, bone, and teeth remains of 169 Paleo-Eskimos from northern Greenland revealed that they were genetically distinct from indigenous groups living in Greenland, northern Canada, the Aleutian Islands, and Siberia.

Their isolation seems to have led to inbreeding, which could have contributed to their sudden disappearance. Other potential causes probably include climate shifts which reduced their traditional food supplies and competition from new migrant groups armed with bows and other comparatively advanced technology. According to anthropologist William Fitzhugh, “the Dorsets were the Hobbits of the eastern Arctic—a very strange and very conservative people who we’re only just getting to know a little bit.”

Even their name causes some controversy—since the term “Eskimo” is not preferred by modern Inuit, the expression “Paleo-Eskimo” to describe previous inhabitants of the region is a bit problematic. The Inuit themselves have an oral history of encounters with a people they called the Tuniit, which may have led to the transfer of certain Tuniit technologies to the Inuit, including how to build snow houses and find soapstone and meteor iron.

8The Monster Of Lake Iliamna

The largest body of fresh water in Alaska, Lake Iliamna is often considered the state’s answer to Loch Ness, with frequent reports of giant creatures lurking in the depths. These creatures have also been sighted in the Kvichak River, which runs from Lake Iliamna to the ocean. The Aleut traditionally avoided fishing in the lake, believing it to be dangerous, while pilots have reported seeing monstrous creatures from the air since the 1940s. The most likely explanation is that the lake hosts a population of white sturgeon, a thick-scaled fish once known to grow up to 6 meters (20 ft) long. (The largest modern sturgeon are usually “only” about half that length.) However, nobody has ever found proof of Lake Iliamna sturgeon, so that remains simply a theory.

More recently, biologist Bruce Wright has suggested that the “monsters” might actually be Pacific sleeper sharks, which can also grow up to 6 meters (20 ft). On the other side of the continent, scientists have documented Greenland sharks navigating the St. Lawrence River. Pacific sleeper sharks are fairly similar to Greenland sharks, suggesting that they might also be able to survive in freshwater. Lake Iliamna is teeming with salmon and other fish, providing an enticing food source for hungry sharks. But, again, no evidence of their presence in the lake has been found, so don’t panic and cancel that Alaskan beach holiday just yet.

7Rain-On-Snow

In recent years, a mysterious meteorological phenomena has been observed in the Arctic, in which northern snows slowly turn into rain. Instead of melting the snow already on the ground, the rainwater seeps through the snowpack, pools on top of the frozen soil, and then freezes into an impenetrable shell which prevents animals from grazing. In 2003, 20,000 musk-ox starved to death following a rain-on-snow event on Canada’s Banks Island. Some of the oxen were so hungry they tried to find food on floating ice and were seen drifting out to sea.

The phenomenon has been reported in Russia, Sweden, Finland, and Canada and could be disastrous for Arctic inhabitants who rely on grazing animal populations for meat and clothing. Some scientists have begun using microwave-imagery satellites to better track the phenomena, as rain-on-snow events cause detectable changes in the microwave radiation signature of the snowpack. Many believe that rain-on-snow events are related to climate change and may increase in the future, with potentially devastating effects.

6Baffin Island Vikings

Ever since the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland was discovered in 1978, archaeologists have been scouring the east coast of North America for other evidence of Norse settlements. In 2012, a dig led by archeologist Patricia Sutherland north of the Arctic Circle on Canada’s Baffin Island discovered some intriguing whetstones, complete with grooves containing traces of a copper alloy (most likely bronze). Such materials were foreign to the Inuit, but were used by Viking smiths.

Other evidence bolstered the idea that there was a Norse presence in the region. In 1999, two strands of cloth were discovered on Baffin Island. The strands differed from the animal sinew cords used by the Inuit, but were identical to yarn made by Norse women in Greenland in the 1400s. Other intriguing artifacts included wooden tally sticks for recording transactions, fragments of Old World rat pelts, and a whalebone shovel similar to those used in Greenland. Many researchers remain skeptical, but Sutherland believes that there was a significant Norse presence in the Canadian Arctic, trading with the locals for luxuries like walrus ivory and Arctic furs.

Sutherland’s most significant claim is that a stone artifact found at a Dorset site in 1960 contained traces of metal and glass and is actually a Norse crucible used for melting bronze. If that’s the case, the artifact would suggest an actual Norse presence, as opposed to Norse trade goods being re-traded between the Dorset in Greenland and Canada.

Controversy erupted when Sutherland was abruptly fired from her post at the Canadian Museum of History. Sutherland intimated during a radio interview that her dismissal was politically motivated, as her work was “out of step with Ottawa’s view of Canadian history.” According to Sutherland, the government was more interested in funding research into British voyages like the Franklin expedition, which would support Canada’s sovereignty claims in the Arctic. However, the museum strongly denied the charges, claiming that she had been “terminated for harassment following an 18-month investigation done by an independent third party.”

5The Zeleny Yar Necropolis

In 2014, archaeologists at Zeleny Yar near the town of Salekhard in the Siberian Arctic discovered 34 shallow graves, suggesting the isolated area was a trading post around the 12th or 13th century AD. Eleven bodies were found with shattered bones or crushed skulls, while five mummified adult males were found shrouded in copper plates and wrapped in reindeer, beaver, wolverine, or bear fur. One of the men had red hair and was buried with an iron hatchet and a bronze belt buckle with a bear design. Three mummified infants were also discovered, wearing copper masks and bound with copper hoops.

All the corpses were buried pointing toward the Gorny Poluy River, which possibly had religious significance. Among the artifacts found were an iron combat knife, a silver medallion, a bronze bird figurine, and a number of bronze bowls originating in Persia. It’s believed that the mummification of the bodies was an accident, caused by the use of non-oxidizing copper and the drop in regional temperature around the 14th century.

In 2015, another set of human remains was discovered, wrapped in a birch bark “cocoon.” MRI scanning detected the presence of metal and the cocoon was opened to reveal the mummified remains of a young boy, aged around six or seven, wrapped in animal fur and equipped with a bronze axe, a bear-shaped pendant, and a number of metal head rings. The elaborate nature of the burial suggests that the boy was from a higher social class than the other bodies. Archaeologists continue to work at the site, trying to discover more about this lost Arctic culture.

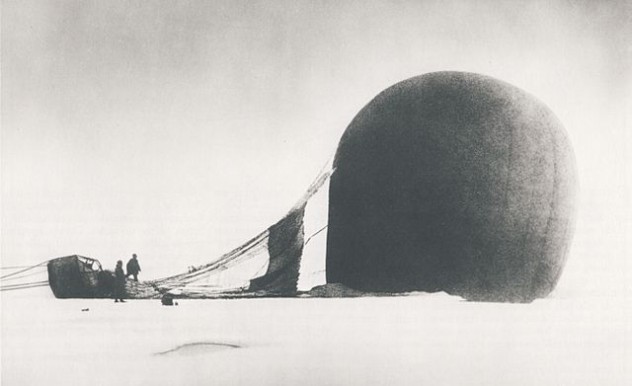

4The Flight Of The Eagle

Salomon August Andree was a young Swedish engineer who became enraptured with balloon technology while studying in the United States in the 1870s. At the time, no expedition had ever succeeded in reaching the North Pole, and Andree became convinced that the feat could best be achieved via hydrogen balloon. Such balloons could theoretically stay in flight for 30 days, though in practice none had stayed up for more than 15. Nevertheless, Andree persuaded himself that if he took off as close to the Pole as possible, he would be able to sail overhead and land in Alaska.

His balloon, named the Ornen (“Eagle”), was built in Paris with a generous financial contribution from the Swedish king. Made from varnished silk, the balloon was almost 30 meters (100 ft) high and weighed 1.5 tons. Andree personally designed a system of guide ropes and sails for maneuvering against the wind and a cookstove that hung outside the basket in order to keep it away from the flammable hydrogen. In July 1897, Andree, civil engineer Knut Fraenkel, and physics professor Nils Strindberg lifted off from the Norwegian island of Svalbard. They were never seen again.

Three decades later, a group of geologists and seal hunters landed on the uninhabited White Island (now Kvitoya) and found the ruins of a camp, complete with a bleached skull which “lay there smiling dreadfully.” Helpfully, there was also a neatly lettered sign reading “Andree’s Polar Expedition of 1897.” Diary entries revealed that the balloon had descended until it was bumping against the ice, probably due to gaps in the sealant allowing hydrogen to escape. The group was forced to abandon the expedition 65 hours after their departure, about 500 kilometers (300 mi) from where they had started. Strindberg took the picture above shortly after the landing.

The trio was well supplied (they even had chocolate cake) and initially survived fairly well. However, an attempt to reach Franz Josef Land failed and the group started to head back toward Spitzbergen. But they only made it to White Island before meeting their mysterious demise.

To this day, we’re not clear how or why the men died. It does seem that Strindberg died first, perhaps of a polar bear attack, and was partially buried in a rock outcropping. A short time later, Andree and Fraenkel died while huddled together in a sleeping bag, leaving valuable equipment casually strewn around the camp. Some speculate that they contracted trichinosis from poorly cooked polar bear meat (Andree’s diary refers to polar bears as “the wandering meat shops of the Arctic”). Another theory claims that they asphyxiated due to gas from a malfunctioning stove. Or perhaps they simply perished due to exposure. In 1930, the remains of the aeronauts were returned to Sweden for an official funeral at Storkyrkan Cathedral.

3Chukchi Sea Blob

In 2009, a group of hunters spotted a mysterious blob in the Chuckchi Sea between Alaska and Russia. It was described as a dark, oily, and hairy mass that stretched for miles through the frigid Arctic waters. Many feared an oil spill, but testing indicated the blob was actually an unusual algae bloom. However, residents were still concerned, as such blooms can be toxic and poison sea life. The Inupiat Inuit, who live along Alaska’s northern coast, said they had never seen anything like it before. Though testing to determine the species of the algae was inconclusive, it has been theorized that it may have been an exotic species that drifted into the region, possibly due to climate change.

Large algal blooms are a natural occurrence given the right nutrients, light, and water temperature. Although it seems odd for a bloom to occur in icy northern waters, it may be that we have underestimated the capacity for life to thrive in such conditions. In 2012, the NASA-sponsored ICESCAPE expedition found a massive phytoplankton bloom under the ice in the Chukchi Sea. The scientists actually expected their phytoplankton-detecting instruments would give a value of zero, but it turned out there was more phytoplankton under the ice than there was in the open water.

2Aurora Sounds

For years, it has been a mainstay of Arctic myth that the aurora borealis makes sounds. The Labrador Inuit believed the spirits of those who died a voluntary or violent death, known as selamiut (“sky-dwellers”), lived near a hole in the heavens and created the aurora to guide the recently deceased, making clapping sounds to communicate with the living. Such stories were generally dismissed by scientists, who insisted the phenomenon was too far away to emit sounds audible to humans.

However, recent research in Finland has indicated that there is some truth to the old stories. According to Aalto University’s Unto Laine, the aurora itself is indeed too far away to make an audible noise, but the clapping noise “is likely caused by the same energetic particles from the sun that create the northern lights far away in the sky. These particles or the geomagnetic disturbance produced by them seem to create sound much closer to the ground.”

While this has shown that there is a noise associated with the aurora, the exact mechanisms that create it remain unclear, and some believe there may be multiple causes. One possibility is electrophonic hearing, which occurs when the auditory nerves are stimulated by electromagnetic fields (hence why some people hear clicking noises during lightning storms). Another possibility is brush discharge, in which the same ionization effects producing the aurora reach ground level at a much lower intensity, causing a buildup of static electricity. That results in tiny sparks discharging into the atmosphere, which might just be audible to human ears.

Another theory involves a phenomenon known as electrophonic transduction. We know auroras can produce VLF radio waves, which can be converted into sound waves by long, thin conductors like grass or hair. So the sounds of the northern lights might reach the ground as radio waves, only to be played back audibly by the foliage.

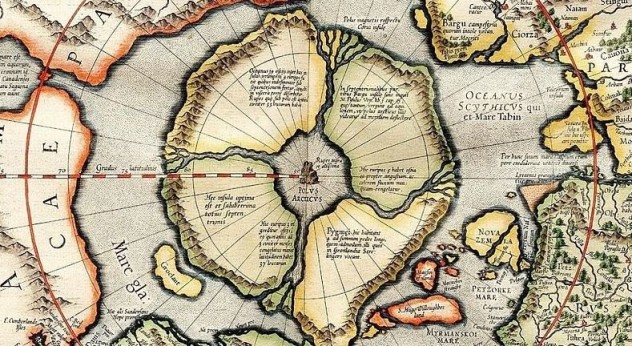

1The Inventio Fortunata

In the 14th century, somebody wrote a travelogue called the Inventio Fortunata (“Discovery Of Fortunata”), which purportedly described a voyage to the far north by a Franciscan priest from Oxford. It was presented to the English crown in 1360 but was lost at some point in the 15th century. A Dutchman named Jacobus Cnoyen included much of the information from the Inventio Fortunata in his own travel book, but that was also lost. Luckily, Cnoyen’s version was extensively quoted in a letter from the Flemish cartographer Gerard Mercator to the English courtier and alchemist John Dee.

In the letter, Mercator includes “word for word everything that I copied out of [Cnoyen’s book] years ago,” so we can be fairly sure we have an accurate version of the Inventio Fortunata‘s description of the Arctic:

In the midst of the four countries is a Whirl-pool, into which there empty these four indrawing Seas which divide the North. And the water rushes round and descends into the Earth just as if one were pouring it through a filter funnel. It is four degrees wide on every side of the Pole, that is to say eight degrees altogether. Except that right under the Pole there lies a bare Rock in the midst of the Sea. Its circumference is almost 33 French miles, and it is all of magnetic Stone.

The Inventio Fortunata was extremely influential on contemporary European descriptions of the Pole, which often cited the giant magnetic rock as the reason compasses pointed north. Knowledge of the Arctic was sketchy during the period, to the point that a mysterious island known as Frisland was often depicted between Iceland and Greenland, possibly as a result of 14th-century Venetian navigators accidentally mapping the coast of Iceland twice.

It took until the 17th century for the Inventio Fortunata‘s influence to finally disappear from maps of the Arctic. Oddly, nobody seems to know who actually wrote it, although Dee believed it was the mathematician Nicolas of Lynn. Others believe the ideas expressed in the work show the influence of Norse exploration and mythology, as the giant whirlpool seems similar to the great abyss Ginnungaggap, which the Norse believed formed the boundary of the oceans.

David Tormsen is not an elf that lives at the North Pole watching your every move. Email him at [email protected].