Travel

Travel  Travel

Travel  Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Phony Myths and Urban Legends That Just Won’t Die

History

History 10 Amazing Roman Epitaphs

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Cool and Creepy Facts about Collecting Tears

Humans

Humans The Ten Most Lethal Gunslingers of the Old West

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Phony Myths and Urban Legends That Just Won’t Die

History

History 10 Amazing Roman Epitaphs

10 Of The Most Intriguing Coins Of All Time

Many millions of coins have been minted throughout history, and we’ve done our best to come up with some of the most beautiful and intriguing ones. Note that the “heads” side of a coin is called the “obverse” while the “tails” side is called the “reverse.”

10 50 Centavos Leper Colony Coin

Colombia, 1921

Most people probably don’t know much about leprosy, because it hasn’t been portrayed accurately in media. Leprosy, now known as Hansen’s disease, is actually very difficult to contract from someone. Nevertheless, it is a serious disease and was feared to the point where people were placed in leper colonies to keep them away from the general public. In some cases, special coinage was minted for fear that the infected might spread the disease through physical contact.

While these coins are not beautiful by any standard, they are quite interesting, because they were minted and circulated only in leper colonies in Colombia. Colombia had three leper colonies where this type of coin was circulated. For reasons of sanitation, the coins would be washed regularly, sometimes as often as weekly, wearing them down much more quickly than regular coins. Because of the repeated washing, leper colony coins are rarely found in good shape, so collectors prize any that don’t show a significant amount of wear.

Leprosy coinage was also used in Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Korea, Nigeria, Thailand, and Venezuela, from roughly 1901–52.

91804 Silver Dollar

US

Considered by many to be the most notorious coin in existence, the 1804 silver dollar is not at all what it seems. The story goes that the US Mint struck 20,000 1804 silver dollars with the previous year’s plate, which ended up stamping the year 1803 on them by mistake. The Mint stopped making silver dollars for three decades until President Jackson ordered a copy of each coin in circulation to be given as a gift to the King of Siam (Thailand). The Mint struck a small amount of 1804 silver dollars, with “1804” stamped on them. This was technically wrong, since the originals had 1803.

The coins became valuable as a result, so a counterfeiter named Theodore Eckfeldt struck several and sold them to a coin store in Philadelphia from 1858–60. All of them had the date 1804, not 1803. The Mint figured out what was going on and tracked down and destroyed all of the coins except for one. The last 1804 Silver Dollar in existence is considered to be one of the most valuable coins in the world and resides at the Smithsonian Institution, even though it is technically a counterfeit coin.

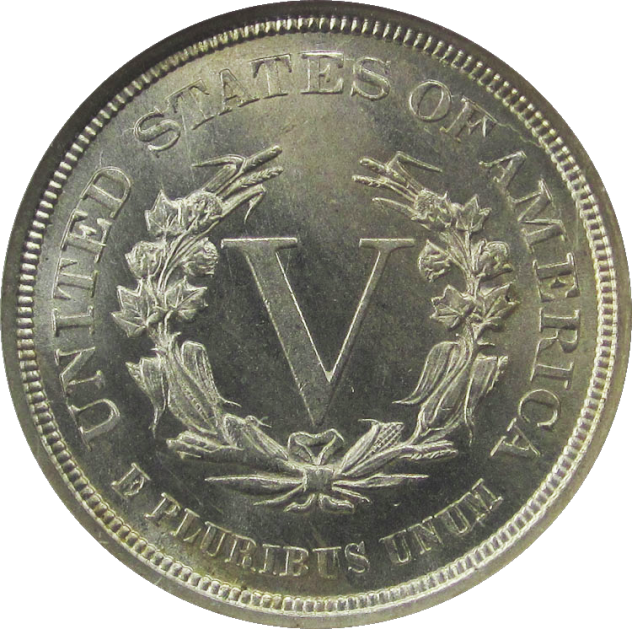

8 No Cents ‘V’ Nickel

US, 1883

Given the opportunity, people can take advantage of others for financial gain. (Shocking, isn’t it?) It happens all the time, and one of the most notable instances of this has to do with a nickel that was minted by the US in 1883. Sporting a large, Roman-numeral five (“V”) on the obverse instead of the words “Five Cents,” the value of the coin was somewhat ambiguous. These nickels happened to be about the same size and appearance as the then-circulating $5 Liberty gold coin, so some people tried gold-plating the 1883 no-cents Liberty nickels and passing them off as the $5 gold coins. The US Mint eventually caught on and added the words “Five Cents” to the obverse of the Liberty nickel to combat the ongoing scam.

There is a story of a man named Josh Tatum, who would gild nickels, purchase five-cent items in a store, and pay for them with the false coins, receiving $4.95 in change. He was eventually tried in court for fraud, having made an estimated $15,000 from his scheme. All charges were dismissed, because it couldn’t be proven that he ever asked anyone for change. There is some argument over whether or not this story is true, since it only surfaced in the 1960s. Interestingly, his name has been linked to the origin of the idiom, “You’re joshing me” as a means of saying that you are trying to fool someone, though this is likely not the true origin of the saying.

7 “Judas’s 30 Pieces Of Silver”

Tyre, Phoenicia, 107 B.C.–106 B.C.

People with even just a passing familiarity with Christianity have probably heard the story of Judas Iscariot’s betrayal of Jesus and the 30 pieces of silver he earned for the act. Matthew 26:14-15 states: “Then one of the 12, called Judas Iscariot, went unto the chief priests, and said unto them, ‘What will ye give me, and I will deliver him unto you?’ And they covenanted with him for 30 pieces of silver.” If that exchange truly took place and those coins were ever found, then they would probably top the list as the most valuable (and possibly cursed) coins of all time. As it stands, there is no physical evidence of Judas’s betrayal of Jesus, so we have to look at the coins of the age to determine what Judas’s silver pieces might have looked like.

At the time, the prominent silver pieces in circulation in Jerusalem were the silver shekels of Tyre, called Tetradrachms of Tyre, which contained roughly 16 grams of silver. These were minted between 126 B.C.–A.D. 57. The obverse features a depiction of Melqart, the god of the Phoenician city of Tyre, who was called Heracles by the Greek. The reverse has the Greek text, TYPOY IEPAS KAI ASULOU, which means “Of Tyre the Holy and Inviolable,” around an intricately drawn eagle.

6 Zhou Dynasty Spade Money

China, 1122 B.C.–500 B.C.

Not all coins were shaped like those we see today. While we have coins with various holes in them and made of different composites of metal, they are almost always disk-shaped. In China, coins took all sorts of shapes, one of which was that of a spade. There were several types of spade money, but they were all shaped like a spade with a socket in the handle that was capable of being attached to something for use as a tool. They were often inscribed with the name of the city where they were cast and were used in the same manner as coins are used today.

The earliest use of spade money comes from the royal house of Zhou in the middle kingdom of the late seventh or early sixth century B.C. The spade became the monetary standard for several centuries and across many different kingdoms, each having different marks and shapes. Some had a rounded end like a modern shovel, while others had a split end with two sharp points rounding out the sides. Though they looked like a spade and could be fastened onto the end of a handle for use as one, they were likely never used as substitute tools due to their poor metal composition and light weight.

5 Wartime Victory Coins

Philippines, 1944

During the occupation of the Philippines by the Japanese in World War II, the Japanese confiscated all Philippine coins and melted them down to be shipped to Japan for use in their war industry. Any coins that escaped this fate were hoarded and hidden until after the war. Most business was conducted with low-denomination paper currency, which was printed by guerrilla units, local municipalities, or military and civilian currency boards that were authorized by General MacArthur or President Quezon’s exiled Commonwealth government.

Prior to the planned liberation of the Philippines, the US Mints in San Francisco and Philadelphia struck millions of coins to replace the ones lost, as well as to commemorate the victory over the Japanese. The coins were referred to as Wartime Alloy Victory Coins and were given out freely upon the liberation of the Philippines. That is why the 1944 Philippines coins bear the mark of the United States of America.

4 The $4 Stella

US, 1879–80

Before we get into the Stella, let’s talk about the euro. You’re probably familiar with the currency that is circulating around most of Europe thanks to the European Union. The euro has been in circulation since 2002 and has replaced the currencies of 19 countries in the EU. What you may not know is that this isn’t the first time this has happened. Back in 1865, much of Europe got together and established the Latin Monetary Union (LMU) and began replacing their coinage with a special new currency modeled after the French franc. The reasons for this were pretty similar to the reasons that the euro went into circulation. The LMU lasted until 1927, but nevertheless mostly owes its failure to World War I.

The United States, not wanting to be left out in the cold, decided it needed to create a coin that was comparable in value to aid in European trade. They designed the $4 Stella (Latin for star) to approximate the new 20-franc coin. The coins were minted until 1880 but were never circulated due to the legislation never passing through the Congress. As a result, the coins are exceptionally rare, and very few were ever produced. Of the two designs (1879 and 1880), there are only approximately 40 originals and 425 re-strikes ever made.

3 Zhou Dynasty Knife Money

China, 600 B.C.–200 B.C.

Similar to the spade money referenced above, knife money was used during the Zhou dynasty in China from around 600 B.C.–200 B.C. Knife money was used in various locales and went by different names. The State of Qi’s money was called the Qi Knife, while Ming Knives got their name from the Yang Kingdom. They were made into somewhat different shapes but always featured a handle, blade, and usually a hole in the base of the handle. The knives were fairly large, approximately 18 centimeters (7 in), and originated from scraping knives used by nomadic hunters and fishermen in northern and eastern China. They were cast in stone molds and were probably not used for any functional purpose. They were minted usually for the commemoration of special events like the inauguration of a new ruling dynasty.

The knives were made from various alloys but were most often made of bronze, and some would be minted for specific purposes. In 1932, needle-tip knives were discovered, which were likely used for commerce between the Chinese and the Huns, who occupied parts of northern China.

2 Bronze Dolphin Coin

Oliba, 500 B.C.–300 B.C.

Here’s another coin that doesn’t fit the usual shape we are all used to: the dolphin coin of Olbia. You may not have heard of Olbia before, but you’re probably familiar with its location. Olbia sat on the northern coast of the Black Sea and was populated by early Greeks and non-Greeks in what is now modern-day Bulgaria and Ukraine. The Olbians identified with the Black Sea bottlenose dolphins so much that they represented them in their coins. To this day, there is a large population of bottlenose dolphins throughout the Black Sea.

These dolphin coins were minted for approximately two centuries. Some of the surviving examples are beautiful depictions of dolphins, while some have degraded into small teardrop-shaped bronze pieces. Most were very small, around 3.6 centimeters (1.4 in), and weighed 1–3 grams on average, though larger examples have been found. They are often found in the hands or mouths of the dead.

1 Silver Thaler Of Leopold I

Holy Roman Empire, 1696

This coin takes the cake in the interesting category, but it is far from beautiful. The obverse of the coin depicts Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, who was called “the Hogmouth,” and you can see why. Due to generations of inbreeding among the Royals, Leopold was the unfortunate recipient of a genetic disorder known as mandibular prognathism, more commonly called “Hapsburg jaw.” As you can see in the image of the coin, Leopold’s lower jaw has grown out considerably further than his upper, making for a prominent feature. The trait has been studied by geneticists for years and is easily seen in images portraying members of the House of Hapsburg, of which Leopold was a member.

The coin is considered by many collectors to be one of the ugliest of all time, though it is still highly sought as a collectible. This is likely due to the cartoonish nature of the depiction of Leopold, which many historians believe was more of a caricature rather than a factual depiction. The coin was approved by the Emperor, who was not nearly as disfigured as the depicted image, though it did likely give rise to his nickname as the Hogmouth.

Jonathan is an amateur graphic artist, illustrator, and game designer with a few independently-published games through his game company, TalkingBull Games. He enjoys researching and writing about history, science, theology, and many other subjects.