Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Great Ancient Chinese Inventions

It is well known that China has an ancient and glorious history, from the feudal periods ending in 222 BC through the three Imperial and Intermediate Eras, up to the Modern era – over 4000 years of dynastic reigns. It may also be well known that China is the source of many wonderful and useful inventions from spaghetti to gunpowder. This list, however, will take a slightly different slant of the topic: Chinese inventions and developments that were not known to or adopted by the Western (European) world for many decades and sometimes centuries after they were common place in China. Some you may be familiar with, others perhaps less so.

As this is not a ‘top 10’ type list, the entries are in a (mostly) chronological order of when they were invented or developed. Please note that these are inventions and technological developments and not discoveries about the natural world – though it is also true that in many cases the Chinese scientists far preceded ‘The West’ in discoveries as well (e.g. William Harvey is credited with discovering the circulation of blood in 1628. It was described in Chinese documents in the 2nd Century BC).

The Chinese started planting crops in rows sometime in the 6th century BC. This technique allows the crops to grow faster and stronger. It facilitates more efficient planting, watering, weeding and harvesting. There is also documentation that they realized that as the wind travels over rows of plants there is less damage. This obvious development was not instituted in the western world for another 2200 years. Master Lu wrote in the “Spring and Autumn Annals”: ‘If the crops are grown in rows they will mature rapidly because they will not interfere with each other’s growth. The horizontal rows must be well drawn, the vertical rows made with skill, for if the lines are straight the wind will pass gently through.’ This text was compiled around 240 BC.

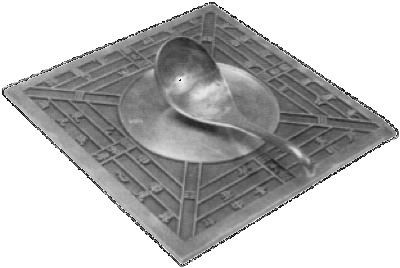

The Chinese developed a lodestone compass to indicate direction sometime in the 4th century BC. These compasses were south pointing and were primarily used on land as divination tools and direct finders. Written in the 4th Century BC, in the Book of the Devil Valley Master it is written: “lodestone makes iron come or it attracts it”. The spoons were made from lodestone, while the plates were of bronze. Thermo-remanence needles were being produced for mariners by the year 1040, with common use recorded by 1119. Thermo-remanence technology, still in use today, was ‘discovered’ by William Gilbert in about 1600.

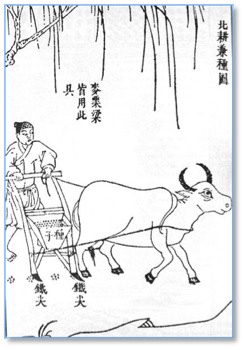

The Seed Drill is used to plant seeds into the soil at a uniform depth and covers it. Without this tool seeds are tossed by hand over the ground resulting in waste and inefficient, uneven growth. Chinese farmers were using seed drills as early as the 2nd Century BC. The first known European instance was a patent issued to Camillo Torello in 1566, but was not adopted by Europeans into general use until the mid 1800’s.

One of the major developments of the ancient Chinese agriculture was the use of the iron moldboard plows. Though probably first developed in the 4th century BC and promoted by the central government, they were popular and common by the Han Dynasty. (So I am using the more conservative date). A major invention was the adjustable strut which, by altering the distance of the blade and the beam, could precisely set the depth of the plow. This technology was not instituted into England and Holland until the 17th century, sparking an abundance of food which some experts say was a necessary prerequisite for the industrial revolution.

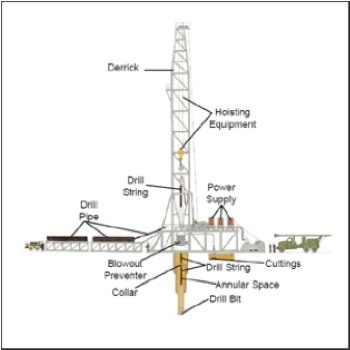

By the first century BC the Chinese had developed the technology for deep drilling boreholes. Some of these reached depths of 4800 feet (about 1.5 km). They used technology that would be easily recognizable to a modern engineer and lay person alike. Derricks would rise as much as 180 feet above the borehole. They stacked rocks with center holes (tube or doughnut shaped) from the surface to the deep stone layer as a guide for their drills (similar to today’s guide tubes). With hemp ropes and bamboo cables reaching deep into the ground, they employed cast iron drills to reach the natural gas they used as a fuel to evaporate water from brine to produce salt. The natural gas was carried via bamboo pipes to where it was needed. There is also some evidence that the gas was used for light. While I could not find exactly when deep drilling was first used by the Europeans, I did not find any evidence prior to the early industrial revolution (mid 18th century). In the United States, the first recorded deep drill was in West Virginia in the 1820s.

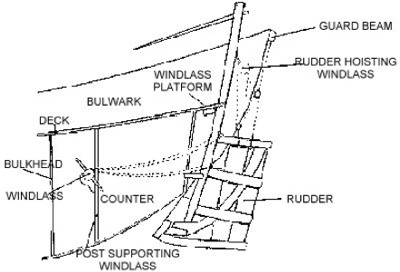

Chinese naval developments occurred far earlier than similar western technology. The first recorded use of rudder technology in the West was in 1180. Chinese pottery models of sophisticated slung axial rudders (enabling the rudder to be lifted in shallow waters) dating from the 1st century have been found. Early rudder technology (c 100 AD) also included the easier to use balanced rudder (where part of the blade was in front of the steering post), first adopted by England in 1843 – some 1700 years later. In another naval development, fenestrated rudders were common on Chinese ships by the 13th century which were not introduced to the west until 1901. Fenestration is the adding of holes to the rudder where it does not affect the steering, yet make the rudder easy to turn. This innovation finally enabled European torpedo boats to use their rudders while traveling at high speed (about 30 knots).

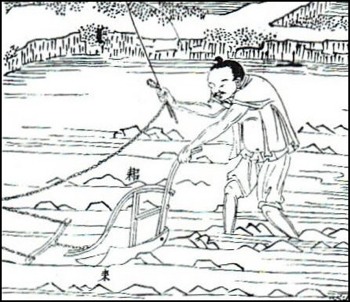

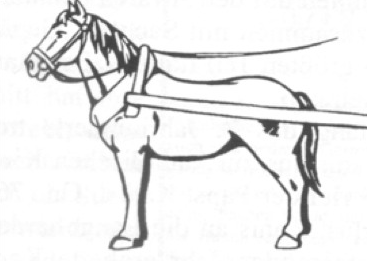

Throat harnesses have been used throughout the world to harness horses to carts and sleds. These harnesses press back on the neck of the horse thus limiting the full strength of the animal. In the late feudal period (4th Century BC) there is pictorial evidence (from the Chinese state of Chu) of a horse with a wooden chest yoke. By the late Han Dynasty the yoke was made from softer straps and was used throughout the country. By the 5Th century, the horse collar (pictured above), which allows the horse to push with its shoulders, was developed. This critical invention was introduced into Europe approximately by 970 and became widespread within 200 years. Because of the greater speed of horses over oxen, as well as greater endurance, agricultural output throughout Europe increased significantly.

Porcelain is a very specific kind of ceramic produced by the extreme temperatures of a kiln. The materials fuse and form a glass and mineral compound known for its strength, translucence and beauty. Invented during the Sui Dynasty (but possibly earlier) and perfected during the Tang Dynasty (618-906), most notably by Tao-Yue (c. 608 – c. 676), Chinese porcelain was highly prized throughout the world. The porcelain of Tao-Yue used a ‘white clay’ that was found on the edge of the Yangtze River, where he lived. By the time of the Sung Dynasty (960-1279) the art of porcelain had reached its peak. In 1708 the German Physicist Tschirnhausen invented European porcelain, thus ending the Chinese monopoly. The picture above is a teabowl with black glaze and leaf pattern from the Southern Sung Dynasty (1127-1279).

As noted above, paper was an early invention of China. One of the first recorded accounts of using hygienic paper was during the Sui Dynasty in 589. In 851 an Arab traveler reported (with some amazement) that the Chinese used paper in place of water to cleanse themselves. By the late 1300’s, approximately 720,000 sheets per year was produced in packages of 1,000 to 10,000 sheets. In colonial times in America (late 1700’s) it was still common to use corn-cobs or leaves. Commercial toilet paper was not introduced until the 1857 and at least one early advertiser noted that their product was ‘splinter free’ – something quite far from today’s ‘ultra-soft’. One rather odd piece of trivia I picked up during my research is that the Romans used a sponge tied to the end of a stick – which may have been the origin of the expression “to grab the wrong end of the stick”.

That paper was invented by the Chinese is well known (by Cai Lun c 50-121 AD), and it is one of the great Chinese inventions. The recipe for this paper still exists and can be followed by today’s artisans. In 868 the first printed book, using full page woodcuts, was produced. About 100 years later the innovations of Bi Sheng, pictured above, (990-1051) were described. Using clay fired characters he made re-usable type and developed typesetting techniques. Though used successfully to produce books, his technology was not perfected until 1298. By contrast, Gutenberg’s bibles – the first European book printed with movable type – were printed in the 1450’s. Interestingly, the Chinese did not start using metal type until the 1490’s.