Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Great Financial Collapses in History

Apparently we’ve been living in some horrific financial crisis for over a year now, and the news simply won’t let you forget about it. You would almost think it was the end of the world, as if this kind of thing is unique to our times and to modern economies, and that it’s a problem nobody has had to deal with before. But history, as always, has something to say about the matter. Plenty of countries have gotten into a sticky situation with their accounts before, and in some of these cases empires have risen, and fallen in no small part due to bad treatment of the books. People have starved, people have gotten rich, and no small number lost their heads.

I’ve tried to give numbers of the deficits in question, but it should be noted the extreme inaccuracy in trying convert money from 600 years ago into modern terms, especially as I am no economist and certainly no mathematician. Early bullion is difficult to convert into modern terms, and in times of economic turmoil the constantly fluctuating values make for a large margin of error. What’s more, early modern and feudal economies are not based on money transactions as we think of them today, and less than 5% of the population would have any money. The first promissory notes used in Medieval Italy would have been entirely used by merchants to transfer money long distances, and were not used by ordinary people until very recently. Furthermore, I have used the pound as a modern comparison rather than the dollar because the pound has existed as a comparison at the time of all these events.

Then: 86,000 silver marks

Now: $41 million

The plan for the Fourth Crusade was to launch an invasion of Cairo, and from there attack Saracen controlled Jerusalem through Egypt. The Crusading movement had lost steam after the failure of the Third Crusade to keep Jerusalem, but nonetheless an army was assembled and the greater part of it gathered at Venice, where Doge Enrico Dandolo had agreed that the Venetian navy would transport them to Egypt. The Venetians had suspended their economy for the better part of a year to construct the transport ships and train almost a third of the population as sailors, and the Doge would not agree to transport the Crusade unless they paid the entire agreed sum of 86,000 silver marks. The Crusaders could only pay 51,000.

Dandolo suggested that, as an alternative form of payment, the Crusade could help recapture the Christian city of Zara on the Dalmatian coast, an act for which the Pope sent a letter excommunicating the Crusaders, but which was luckily misplaced.

Emperor Isaac II of the Byzantine Empire had been forced into exile by his brother Alexius in 1195, who had then gone on a populist rampage, killing the mistrusted Latin population of Constantinople, an act which did not endear the Byzantines to the Venetians. Isaac’s son offered the Crusaders 200,000 marks to help him capture Constantinople and reclaim the throne, and the debt crippled Crusade was easy to convince. When the Crusader’s fee was not met – due to the ransacking of the treasury by the fleeing usurper – the Crusaders sacked the city, pillaging up to 900,000 marks worth of valuables, burning much of the city. The Venetians and other leaders of the Crusade took direct control of the city, forming a corrupt and decadent regime that squandered what was left of Constantinople’s grandeur. The Byzantine Empire, last remnant of the Roman Empire split into several separate kingdoms, and never recovered.

Then: £400,000

Now: $56 million

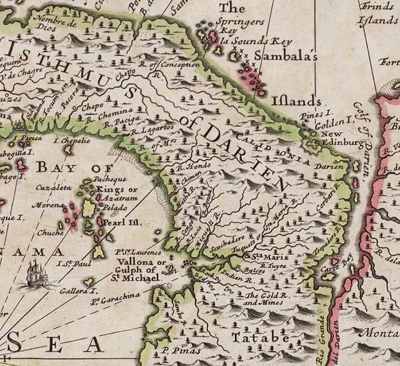

In 1695 the Kingdom of Scotland chartered the Company of Scotland in an attempt to bolster its limited finances by joining the other major trading empires of the world in Africa and the Indies. William Paterson, a successful Scottish entrepreneur who had been a founder of the Bank of England, convinced Scottish investors they could dominate East Asian trade by establishing a colony on the Isthmus of Panama, transporting goods by land from the Pacific coast to the Atlantic so that ships could avoid the long and treacherous voyage around South America. The plan, which he had unsuccessfully tried to market to the English government under James II, is known as the Darién Scheme.

Investors from all social strata gave £400,000 to the scheme, and the first ships set sail in 1698, arriving at the Bay of Darién in November, where they began building the colony of New Caledonia. Paterson’s plans were far fetched, however, and the difficulties of life in Central America were not something he had witnessed or researched. His own wife was dead before the colonists even arrived in the mosquito plagued bay, and within 7 months hundreds more were dead from starvation, fever and skirmishes with the Spanish, who considered the area part of their colony of New Granada. Supplies were limited as the English colonies had been ordered not to assist the Scots for fear of angering the Spanish. Even had the colony been properly established, the logistics of hauling cargo across densely forested and rugged terrain would surely have been impossible.

After a second expedition had set sail, without knowing of the already interminable situation, the colony was abandoned, only a single ship returning from the disaster. With almost half of all Scotland’s money sunk into the scheme, only the most die hard Jacobites were against it when the English parliament offered to bail them out as incentive to agree to the 1707 Act of Union, combining the two nations into the United Kingdom.

Then: £240,000

Now: $193 million

Many people will be familiar with the English King Edward I from Braveheart, which we all now know to be a historically dubious, if entertaining, movie. Well, one thing was true about Edward: he was definitely a brutal, megalomaniacal tyrant, and before he turned his malefic gaze to Scotland he was concerned with Wales. Following the Norman invasion, the osmosis of Norman nobility across the Welsh border had opened up feudal debates over lordship between the nobility of the two countries.

In 1277, Edward I, who had ascended the throne 5 years earlier, led an army 15,000 strong into Wales after the Welsh leader Llywelyn ap Gruffud refused to acknowledge Edward’s sovereignty. Llywelyn had previously been confirmed as the sole authority in Wales by the Treaty of Worcester, having allied with Simon de Montfort, the baron whose civil war against King Henry III resulted in the convening of the very first parliament. The first invasion forced Llywelyn to accept a peace treaty limiting his control to the land west of Conway Castle. In 1282, the Welsh rose in rebellion and Edward led an even larger army into the country. Llywelyn was killed in a minor skirmish in the centre of the country.

The cost of the invasions, and the building of a massive network of castles to cow the local population and subsume their culture, was around £240,000, more than 10 times the annual income of the kingdom, and a great deal of the sum was borrowed from Jewish bankers in London. Very soon, no doubt in a fit of conscience, Edward outlawed money-lending and forced the Jews to wear yellow identity badges. Within a year of the conquest he had the heads of their households arrested, and hanged over 300 in the Tower of London, expelling the rest of the population, handily erasing a good portion of his debt, even receiving a tax bonus from the Catholic Church for the immensely popular act. One positive effect of the invasion (always look on the bright side, I suppose) was that a large part of the cost had to be paid by tax grants which were acquired by summoning a parliament, the necessity of which added to the long process whereby a (somewhat) democratic institution took more and more power away from the monarch.

Then: 2 billion livres-tournois

Now: $6 billion

When Louis XV died he left his historically maligned successor Louis XVI with a handbag full of troubles, having been engaged in four catastrophic wars in the 18th century. While the first War of the Austrian Succession and the American War of Independence technically weren’t losses, France came away with less than she put in. The first failed to restore the previous balance of power in central Europe, while after the latter war the Americans repaid French assistance by going straight back to trading with Britain instead of favoring French trade. Meanwhile the Seven Years’ War (see below) shore away almost all of France’s overseas empire.

Louis XVI was not a complete dithering fool, as he is sometimes portrayed – he did try to do something about the imminent financial meltdown – he was largely a weak, impotent man who lacked the gumption to force the necessary changes through. The prospect of imposing taxes on the tax exempt nobility and clergy to offset the debt failed outright, being scorned and virtually ignored. France lacked an equivalent to the Bank of England, which allowed the UK to manage a considerably larger debt in the same period, to help manage the problem.

The strains on ordinary people mounted. Food prices rose, squalor spread disease through the cities and widespread famine broke out. Soldiers were unpaid, unemployment was rife, and all the while the nobility paid no tax and enjoyed a lifestyle of excess and power, and in 1789 the Revolution broke out.

Then: 86 million ducats

Now: $11 billion

Philip II ruled Spain during the ‘Golden Age’ of its superpower global empire, yet in his lifetime also saw the beginning of its long decline. Already burdened with a 36 million ducat debt by his predecessor, the poorness of Spain itself meant low tax revenues, so Philip relied heavily on gold shipped from the Americas to supplement his treasury. Along with the tax burden and increased state spending this caused high inflation, which devalued the currency and harmed Spanish industries. The unreliability of New World gold during war time caused the first bankruptcy of a nation in modern history, in 1557. To cover the costs of multiple wars Philip began borrowing from Italian bankers, who kept financing his wars despite repeated failure to keep up interest payments, sending Spanish debt payments up to 40% of the country’s yearly income and resulting in further bankruptcies in 1560, 1576 and 1596.

Eventually the debt was 85 million ducats, when the state’s yearly income was only 9 million. Repeated military disasters resulted in the casual squandering of millions. When Philip lost control of England after his wife, Queen Mary, died, leaving England in the control of Protestant Queen Elizabeth I, he financed an armada to eliminate protestantism before it could spread to Europe. When the armada sank, over 10 million ducats sank with it, while privateers like Francis Drake captured Spanish Gold Galleons. The Dutch Revolt was particularly damaging as the wages of soldiers ended up going into the emergent Dutch economy instead of Spain’s, and the value of Spanish exports and imports were damaged.

Spain’s economic woes meant that it could not maintain its stranglehold on New World colonialism, and following Philip’s reign it was overtaken by the Dutch, the French and then the English. The Spanish navy lost its position to the emerging power of the Royal Navy, and Spanish holdings in Europe were soon lost.

Then: £200 million

Now: $14 billion

When Tsar Nicholas I described the Ottoman Empire as the ‘sick man of Europe’, he described a nation incapable of keeping up with the advances of European powers, and in the late 19th century it was still administered in an almost medieval fashion. Rail transport was virtually non existent, industry was still based on small scale manual manufacturing, and the economy was based mostly on taxation of the poor, largely agrarian population. Up until 1853 the Empire had slowly begun to develop its infrastructure, but was unable to advance very far on its limited finances, and was wary of going into debt with European nations.

The Crimean War changed that stance, however, and the Ottoman Imperial Bank was established by British and French financiers to provide a line of credit to the government. The government began defaulting on its interest payments in 1875, however, and the province of Egypt, nominally part of the Empire but partially autonomous, was occupied by the British in 1883 to take control of the Public Debt. The Ottoman government was now firmly dependent on Britain and France for its finances, and much of the new infrastructure was owned by their investors.

The end came with World War One. With the Empire still underdeveloped and its satellites picked off by its creditors, the British invasion took Mesopotamia (Iraq), Palestine, Lebanon and Syria, and the Sykes-Picoult agreement divided these former holdings between the French and British Empires. Finally, in 1923, after occupation by the Allied powers, the Empire was dissolved and the Republic of Turkey formed in its place.

Then: £133 milion

Now: $18 billion

When the French started building a ring of forts along the Ohio river to box the English colonies against the sea, it was quite evident that something big was brewing. That something would turn out to be the Seven Years’ War, a truly global conflict primarily between the United Kingdom and France for domination of the colonies in North America, the West Indies and India, while a continental war between Prussia, Austria and their allies raged in Europe.

The cost of such a vast war on states with a still fledgling understanding of mercantile economics was great, but the difference between Britain and France was the Bank of England and the possibilities of government borrowing, which prime minister William Pitt seized upon, and which his French counterparts, under Louis XV, could not. Louis’ war cabinet was divided over focusing their efforts in the colonies, or focusing on the war in Europe. The French decided to focus on Europe, and planned an invasion of England through Scotland that would force a peace treaty giving colonial dominance to France.

Pitt’s evaluation was the opposite, and he determined that complete victory in every theatre was worth paying any price, and that failure anywhere was complete failure. A vast amount of money was poured into the colonial war effort, and paid off handsomely with James Wolfe’s victory at Quebec, at Pondicherry in India, and at Minden in Germany. To finally scupper the French plans, Admiral Hawke destroyed the French fleet intended to escort the invasion barges to Scotland at the Battle of Quiberon bay. The cost of the war resulted in unpopular measures such as the very first income tax and a tax on windows which may have coined the phrase ‘daylight robbery’.

Then: 50 billion rubles

Now: $270 billion

Following Imperial Russia’s disastrous defeat in World War One, the government faced debts of up to 50 billion rubles and near bankruptcy. Industries collapsed, and the chaotic disruption of the transportation network caused many industrial closures and resulted in huge unemployment, while the wages of those who kept their jobs fell drastically. Facing starvation from poverty, the disrupted food supply and rampant inflation due to the overprinting of money to cover the war deficit, people abandoned their jobs and cities to look for food. Soldiers lacked adequate equipment, and thousands froze in the streets.

Mass strikes and riots began in Petrograd, formerly St. Petersburg, and spread across the country. The Bolsheviks, who had seized a portion of political power after the February Revolution’s institution of a limited constitutional government, organized strikers into militias. It was easy to convince people that their suffering was due to the greed and ineptitude of the rich and the corrupt, oppressive monarchy. In July 1917, the Provisional Government ordered that a demonstration in Petrograd be quelled, and violence broke out as soldiers opened fire on the crowds. The following month a rogue general led his troops in an attack against the Bolsheviks in the city, and was beaten back by militia, sailors and strikers. Uprisings began two months later, taking over the Winter Palace and government facilities, and in 1922 the USSR formally began.

Then: 269 billion gold marks

Now: $420 billion

In 1919, the Treaty of Versailles stated that Germany and its allies were responsible for all damage done to allied countries, and in 1921 it was decided that Germany owed 269 billion gold marks, or 23 billion pounds, in monetary and material reparations. Germany began defaulting on its payments by 1922, stalling shipments of coal and wood to France, prompting the French to occupy the valuable Ruhr valley in order to take the raw materials themselves. This in turn led to sabotage and strikes, and weakened the Versailles Treaty with both sides claiming the other was dishonoring one or more clauses.

In 1924, the Dawes plan reduced Germany’s payments to 112 billion marks, following widespread criticism that the sums were impossible for a heavily destabilized economy to manage. The government printed more and more money to try and cover the economic downturn and pay the debt, but the flood of money caused prices to rise and required more money. Economists hurriedly tried to stabilize the mark by buying it in foreign markets with valuable gold and materials, but this only caused the its value to plummet further, along with the loss of stable currency. The effects on the poor and middle classes was devastating: pensions were destroyed, savings vanished, and, in 1923, the cost of a loaf of bread was 200 million marks, and even if you had that much (carried in a wheelbarrow, usually) its value might have depreciated by the time you reached the baker’s.

All of this created in ordinary Germans the feeling that they were being persecuted, starved and impoverished, for something that was not their fault. It was already commonly thought that the army had not lost the war, but that it was Weimar politicians, bolsheviks, socialists and Jews who had caused defeat, as well as the idea that the Triple Entente had begun the war in the first place. When Adolf Hitler became chancellor in 1933 he exploited the ‘Stab in the Back’ myth to its fullest, and thus the Nazi party stormed into power on a new wave of nationalism.

Then: £21 billion

Now: $872 billion

At the end of World War 2 most of Europe was in financial, and literal, ruins. The cost of maintaining the army, navy and newly burgeoning air force left the United Kingdom in economic peril, with the American Lend-Lease act supplying ten billion dollar’s worth of vital equipment. When Lend-Lease was terminated the equipment, still sorely needed for the recovery effort, was loaned at the cost of £1 billion, but this was just a drop in the ocean. The financial situation was dire, and resulted in vast and rapid socio-political changes in the Empire. The Royal Navy was the first major target, and by 1960 1100 of its 1300 ships were dismantled and sold for scrap, and the shipyards that had built two thirds of the world’s ships were closed or limited in capacity.

At home wartime rationing continued years into the peace, and housing shortages were endemic for decades, breeding cultural and economic stagnation, unemployment and homelessness. Later decades were characterized by constant strikes, riots, power shortages and reading by candlelight, economic booms followed by economic busts, and repeated nationalizations and privatizations by opposing parties with different ideas about how to save the economy.

Abroad, the Empire, now a crippling burden, was quickly taken apart. Almost nobody in the modern age would say the end of colonialism was a bad thing, however the rapid pace of decolonization unwittingly created some of the most volatile political conflicts of the modern age. Lines were hastily drawn on maps, countries split and ushered awkwardly into self-governance, and countries painfully partitioned. Israel was carved out of Palestine. India and Pakistan were partitioned with immediate sectarian violence around the new border, culminating in a modern day Asian Cold War over Kashmir between the two nuclear powers. Many African colonies fell into ethnic warfare and sadistic dictatorships under the likes of Robert Mugabe and Idi Amin, while in the Middle East Iraq and Iran both saw their British supported monarchs overthrown by repressive dictatorships. If you could salvage any good thing from the mess of imperialism it might be the ironic legacy of democratic parliamentary systems in most of the former colonies.

The war loan was finally paid off in 2006.