Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Top 10 Sporting Airline Disasters

Travel is a fact of life for many athletes, and since the advent of air transportation, many sports teams have chosen to forgo the ship, train or bus and make the trip via air. Over the last 60 years, as air travel became routine, several sports teams failed to arrive at their planned destination. What is inspiring is that in so many of these tragedies, the teams decided to play on, usually with junior team members, volunteers, athletes from other sports and even athletes loaned from opposing teams. Here are the top ten airplane disasters involving sports teams.

The 1987 Alianza Lima air disaster took place on December 8, 1987, when a Peruvian Navy Fokker F27-400M, chartered by Peruvian football club Alianza Lima, plunged into the Pacific Ocean six miles short of its destination. On board the flight were a total of 44 players, managers, staff, cheerleaders and crewmembers, of which only the pilot survived the accident. The team was returning from a Peruvian league match when the aircrew thought they noticed a malfunctioning indicator on the control panel, which appeared to show the planes landing gear had not deployed. The pilot requested a flyby of the control tower so that spotters on the ground could confirm that the plane’s landing gear was down and locked. Upon receiving visual confirmation of safe configuration for landing, the plane went around for another attempt at a landing. The Fokker flew too low and plunged into the Pacific.

Following the crash, the Peruvian Navy shut itself off from the press, and did not release the results of its investigation, nor did it allow private investigations to take place. Allegations were made that the accident had been caused by the aircraft’s shoddy mechanical condition, and the Navy concealed the truth in order to save face. It was not until 2006 that the results of the official inquiry into the cause of the disaster came to light. The investigation cited the pilot’s lack of night flying experience, his misreading of the emergency procedures related to the landing gear issue, and the aircraft’s poor mechanical condition as contributing factors to the accident. The Peruvian Football Federation chose not to end the football season early, despite the loss of what amounted to the majority of Alianza’s team; the club played their last few matches with retired volunteers, players from its youth teams, and players loaned by a Chilean club. The accident was disastrous for Alianza, who lost their most promising squad in a decade.

LOT Polish Airlines Flight 007 crashed near Warsaw, Poland, on March 14, 1980, due to mechanical failure as the crew aborted a landing and attempted to go-around. All 87 crew and passengers died. On board were many members of the 1980 US amateur boxing team, many of whom were contenders to qualify for the 1980 US Olympic Boxing Team (the US subsequently boycotted the 1980 Olympics in Moscow). The team was going to Poland for boxing matches against Polish and Russian amateur boxers. Flight 007 departed New York City at 21:18, and after nine hours of an uneventful flight, it was approaching Warsaw Airport at 11:13 local time. During their final approach, about one minute before the landing, the crew reported that the landing gear indicator light was not operating, and that they would go-around and allow the flight engineer to check if it was caused by a burnt-out fuse or light bulb, or if there was actually some problem with the gears deploying.

Nine seconds after the last voice transmission the aircraft suddenly entered a steep dive. At 11:14:35, after 26 seconds of uncontrolled descent, the aircraft clipped a tree with its right wing and impacted the ice-covered moat of a 19th-century military fortress. At the last moment the pilot, using nothing but the plane’s ailerons, managed to avoid hitting a correctional facility for teenagers. On impact, the aircraft disintegrated; a large part of the main hull submerged in the moat. The moat had to be drained to allow the air crash investigation team to recover parts of the disintegrated plane. The body of the pilot was found lying on the street about sixty meters from the crash site; other bodies were scattered between the plane parts. According to the Polish government’s Special Disaster Commission, the crash was caused by defects in materials, faults in the manufacturing process of the jet engine’s shaft, and weaknesses in the design of its turbine.

Not on board the plane were other members of the US boxing team, including Johnny “Bump City” Bumphus who made the US Olympic team at 139 pounds. Bumphus would later go on to a successful professional boxing career and earn the title of WBA Light Welterweight Champion.

On December 13,1977, a chartered DC-3 carrying the entire University of Evansville basketball team crashed in a field near the Evansville Regional Airport. Every member of the team and coaching staff on the plane was killed. One player was not able to attend the game and thus was not on the plane; however, soon afterward, he was killed in an automobile accident. The team was on its way to Nashville, Tennessee, for a game against Middle Tennessee University when it crashed in rain and fog about 90 seconds after take off from the Evansville Airport. Twenty-nine people died in the crash including fourteen members of the basketball team and its coach. Three people did survive the crash but died shortly thereafter. The NTSB determined the cause of the crash was improper weight balance and the failure of the crew to remove external safety locks.

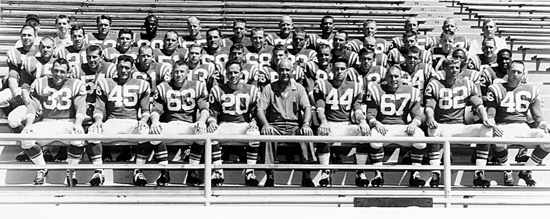

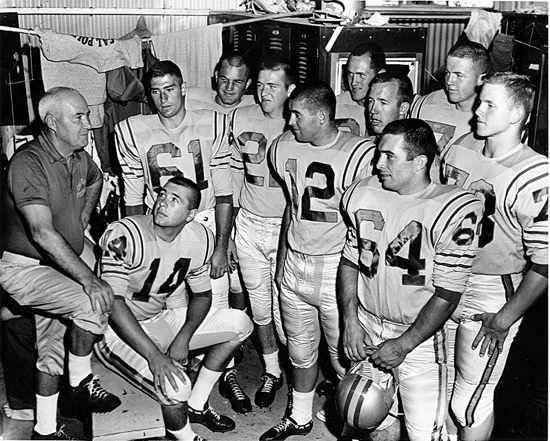

The Cal Poly football team plane crash occurred on October 29, 1960, when a twin-engine C-46 prop liner, carrying the California Polytechnic State University football team, crashed on takeoff at the Toledo Express Airport in Toledo, Ohio. The World War II vintage aircraft broke in two and caught fire on impact. Twenty-two of the forty-eight people on board were killed, including sixteen players. The follow up investigation concluded that the aircraft had been overloaded by 2,000 lbs above its maximum certificated gross takeoff weight and that there was a partial power loss in the left engine prior to the crash. Prior to takeoff the weather at the airport steadily deteriorated until by the time of the accident the visibility was zero. Because of this crash, the FAA published a notice prohibiting takeoff for commercial aircraft when the visibility is below 1/4 mile, or the runway visual range is below 2000 ft.

The pilot who made the decision to take off was flying on a license that had been revoked, but was allowed to fly pending an appeal. At the time of the crash, Bowling Green State had been the easternmost opposing school that the Cal Poly football team had ever traveled to. The university canceled the final three games of the 1960 season. Cal Poly alumnus and NFL Hall of Fame coach John Madden’s fear of flying is commonly attributed to the crash, although he has said it instead stems from claustrophobia. Madden, who played football for Cal Poly from 1957–58, and was coaching at the nearby Allan Hancock Junior College at the time of the crash, knew many passengers aboard the plane. As a result of the crash, Cal Poly did not play any road games outside California until 1969.

On Friday October 2, 1970, the Wichita State University football team was aboard a Martin 4-0-4 aircraft when it crashed into a mountain eight miles west of Silver Plume, Colorado. The airplane carried 36 passengers and a crew of four; 29 were killed at the scene and two later died of their injuries. It was one of two planes carrying the Wichita State University football team to Logan, Utah, for a game against Utah State University. The two aircraft were dubbed “Gold” and “Black”, after the team colors. “Gold”, the plane that would crash, carried the starting players, coaches and boosters, while “Black” transported the backup players and other support personnel. The pilot flying “Gold” had not been rated to flay a Martin 4-0-4. In addition, he planned to take a scenic route, which would depart the normal flight path going over the Rocky Mountains. The crew flying the other team aircraft, “Black”, would adhere to the original flight plan and take a more northerly route towards Wyoming after departing Denver, using a designated airway. This planned route allowed more time to gain altitude for the climb over the Rocky Mountains.

While the aircraft were being refueled and serviced in Denver, the pilot of the Gold Plane purchased a map to use to point out landmarks on the scenic route he planned for the final leg of the journey. After take-off in clear weather, the two planes took divergent paths away from Denver. Having departed the normal flight path, the overloaded Gold plane entered the mountains and became trapped in a box canyon and was unable to escape. At 1:14 p.m. the “Gold” aircraft struck trees on Mount Trelease, 1,600 feet below the summit, and crashed. The NTSB report stated a belief that many on board survived the initial impact, and a few survivors escaped the fuselage before it burst into flames, killing any others who had survived the crash.

The NTSB found the primary cause of the crash was “The intentional operation of the aircraft over a mountain valley route at an altitude from which the aircraft could neither climb over the obstructing terrain ahead, nor execute a successful course reversal. The game was canceled, and the Utah State football team held a memorial service at the stadium where the game was to be played and placed a wreath on the 50-yard line. The remaining Wichita team, with the NCAA allowing freshman players to fill out the squad, decided to continue the 1970 season. Wichita State ended varsity football after the 1986 season. Wichita State University built a memorial for those who had died from the crash called Memorial ’70. Every year on October 2, at 9 am, a wreath is placed at this memorial.

The Superga air disaster took place on Wednesday, 4 May, 1949, when a plane carrying almost the entire Torino A.C. football squad, popularly known as Il Grande Torino, crashed into the hill of Superga, near Turin, killing all 31 aboard, including 18 players, club officials, journalists accompanying the team and the plane’s crew. The Italian Airlines Fiat G212CP airplane carrying the team flew into a thunderstorm on the approach to Turin and encountered conditions of low cloud and poor visibility. They were forced to descend to be able to fly visually. While descending for Turin, the aircraft crashed against the base of the rear wall of the Basilica complex at the top of the hill of Superga. Italian authorities cited low cloud, poor radio aids and an error in navigation as factors contributing to the accident.

The emotional impact the crash made on Italian sports fans was profound, as it claimed the lives of the players of a legendary team which had won the last Serie A title before the league play was interrupted in 1944 by World War II and had then returned after the conflict to win four consecutive titles (1946–1949). At the time of the crash, Torino A.C. was leading Serie A with four games left to play in the season. The club carried on by fielding its youth team (Primavera) and in a sign of respect their opponents in each of these matches (Genoa, Palermo, Sampdoria, and Fiorentina) also fielded their youth sides. The disaster seriously weakened the Italian national team, which had included up to 10 Torino players. Torino itself would not claim another title until 1976. Of the entire squad only one player remained: Sauro Tomà missed the trip to Portugal due to injury.

On 6 February, 1958, British European Airways Flight 609 crashed on its third attempt to take off from a slush-covered runway at Munich-Riem Airport in Munich, West Germany. On board the plane was the Manchester United football team, nicknamed the “Busby Babes”, along with a number of supporters and journalists. 23 of the 44 people on board the aircraft died in the crash. The team was returning from a European Cup match in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, against Red Star Belgrade, but had to make a stop in Munich for refueling, as a non-stop trip from Belgrade to Manchester was out of the aircraft’s range. After refueling, the pilots attempted to take off twice, but had to abandon both attempts due to problems with the port engine. Fearing that they would get too far behind schedule, the Captain rejected an overnight stay in Munich in favor of a third take-off attempt.

By the time of the third attempt, it had begun to snow, causing a layer of slush to build up at the end of the runway. When the aircraft hit the slush, it lost velocity, making take-off impossible. It ploughed through a fence past the end of the runway, before the port wing hit a nearby house and was torn off. Fearing that the aircraft might explode, the Captain tried to get the survivors as far away as possible. Despite the risk of explosion, goalkeeper Harry Gregg remained behind to pull survivors from the wreckage. An investigation by the West German airport authorities originally blamed the Captain for the crash, claiming that he had failed to de-ice the wings of the aircraft, despite statements to the contrary from eyewitnesses. It was later established that the crash had, in fact, been caused by the build-up of slush on the runway, which had resulted in the aircraft being unable to achieve take-off velocity.

On February 15, 1961, Sabena Flight 548, a Boeing 707 bound from New York to Brussels Belgium, crashed during the approach for landing. All 72 on board were killed, as well as one person on the ground. Among the dead was the entire United States Figure Skating team, who were en route to the 1961 World Championships in Prague, Czechoslovakia. There was no indication of trouble on board the plane until it approached the Brussels airport. The pilot had to circle the airport while waiting for a small plane to clear the runway. Then, according to eyewitnesses, the plane began to climb and bank erratically and crashed suddenly in a field near the hamlet of Berg. The wreckage burst into flames. All aboard were killed instantly. A farmer working in the fields was killed by a piece of aluminum shrapnel, and another farmer had his leg amputated by flying debris from the plane.

The exact cause of the crash was never determined beyond reasonable doubt, but investigators suspected that the aircraft might have been brought down by a failure of the stabilizer adjusting mechanism. All 18 athletes of the 1961 U.S. figure skating team and 16 family members, coaches and officials died in the crash. The loss of the U.S. team was considered so catastrophic for the sport that the 1961 World Figure Skating Championships were cancelled. American President, John F. Kennedy, issued a statement of condolence from the White House. He was particularly shocked by the disaster. One of the skaters killed in the crash, Dudley Richards, was a personal friend of President Kennedy and his brother Ted Kennedy, from summers spent at Hyannis Port, Massachusetts. Because the casualties included many of the top American coaches as well as the athletes, the crash was a devastating blow to the U.S. Figure Skating program, which had enjoyed a position of dominance in the sport in the 1950s.

The Zambian national football team was flying on a military plane on its way to Senegal for a 1994 World Cup qualification match, when the plane crashed in the late evening of April 27, 1993. All 30 passengers and crew, including 18 players, as well as the national team coach and support staff, were lost in the accident. Two other members of the national team, who were playing in other countries and who had made other flight arrangements to attend the game, were not aboard and survived.

The flight from Zambia to Senegal required three refueling stops and at the first stop, in the Congo, engine problems were noted. Despite this, the flight continued and a few minutes after taking off from a second stop in Libreville, Gabon, one of the engines caught fire and failed. The pilot, who was tired from already having flown back from Mauritius earlier that day, then shut down the wrong engine, causing the plane to lose all power during the climb out of Libreville Airport. The plane fell from the sky and crashed into the water 500m offshore.

A new team was quickly assembled and faced up to the difficult task of having to complete Zambia’s World Cup qualifiers and then prepare for the upcoming African Nations Cup, which was only months away. The resurrected team defied the odds and reached the final against Nigeria, only to lose. In spite of the loss, the Zambian side returned home as national heroes. After the crash, Zambia fell into seven days of official mourning. The 18 players, coaches and crew members were buried there with official honors as tens of thousands of fans poured into the capital’s streets and grieved for what many said was one of Africa’s greatest teams. An official report into the plane crash blamed a mechanical fault in the left engine and the pilot inadvertently shutting off fuel to the functioning right engine by mistake because of a “poor indicator light bulb”.

Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, also known as the Miracle in the Andes, was a chartered flight carrying 45 people, including a rugby team and their friends, family and associates that crashed in the Andes on October 13, 1972. The last of the 16 survivors were rescued on December 23, 1972. The story of the Andes Survivors is well known; popularized by the book “Alive” and the 1993 film of the same name. On Friday the 13th of October, 1972, a Uruguayan Air Force twin turboprop Fairchild FH-227D was flying over the Andes carrying members of the Old Christians Club rugby union team from Montevideo, Uruguay, to play a match in Santiago, Chile.

Due to bad weather and limitations of the airplane, the flight could not fly over the Andes Mountains and instead had to proceed through one of the “passes” through the mountains, to reach Chile. The pilots misjudged their position and, thinking they were at the pass, flew instead into a mountain, leading to a controlled flight into terrain. But the plane did not smash head long into the mountain. In a last ditch effort to gain altitude and clear the top of the mountain, the pilots clipped the peak at 4,200 meters (13,800 ft), neatly severing the right wing, which was thrown back with such force that it cut off the tail, leaving a gaping hole in the rear of the fuselage. The plane then clipped a second peak, which severed the left wing and left the plane as just a fuselage flying through the air. The fuselage hit the ground and slid down a steep mountain slope before finally coming to rest in a snow bank.

Of the 45 people on the plane, 12 died in the crash or shortly thereafter; another five had died by the next morning, and one more succumbed to injuries on the eighth day. The remaining 27 faced severe difficulties in surviving high in the freezing mountains. The survivors had little food and no source of heat in the harsh conditions, at over 3,600 meters (11,800 ft) altitude. Faced with starvation and radio news reports that the search for them had been abandoned, the survivors fed on the dead passengers who had been preserved in the snow. Rescuers did not learn of the survivors until 72 days after the crash, when passengers Nando Parrado and Roberto Canessa, after a 12-day trek across the Andes, found a Chilean huaso, who gave them food and then alerted authorities about the existence of the other survivors. Only sixteen would survive. Their survival in the high mountains of the Andes and final rescue just before Christmas 1972 would become known as The Miracle in the Andes.

The year 1970 was to prove a grim year for college football program travel. Southern Airways Flight 932 was a chartered commercial jet flight from Kinston, North Carolina, to Ceredo, West Virginia. At 7:35 pm on November 14, 1970, the aircraft crashed into a hill just short of the airport, killing all 75 people on board. The plane was carrying 37 members of the Marshall University Thundering Herd football squad, eight members of the coaching staff, 25 boosters, four flight crew members, and one employee of the charter company. The team was returning home after a 17–14 loss against the East Carolina Pirates. At the time, Marshall’s athletic teams rarely traveled by plane, with most away games within easy driving distance of the campus. The team had originally planned to cancel the flight, but changed plans and chartered the Southern Airways DC-9.

On the return flight to West Virginia the flight crew were informed to descend to 5,000 feet. The controllers had advised the crew that there was “rain, fog, smoke and a ragged ceiling” making landing more difficult but not impossible. The airliner was on its final approach when it collided with the tops of trees on a hillside 5,543 feet (1,690 m) west of runway 12. As a result of the impact, the plane burst into flames and created a swath of charred ground 95 feet (29 m) wide and 279 feet (85 m) long. According to the official NTSB report, the accident was “unsurvivable”. The aircraft had “dipped to the right, almost inverted and had crashed into a hollow ‘nose-first’”. The fire was very intense and the remains of six individuals that were discovered on the plane were never identified.

The National Transportation Safety Board investigation concluded that the crash was either the result of the crew misreading the airplane instrumentation, or a faulty altimeter. Many team boosters and prominent citizens were on the plane. Seventy children lost at least one parent in the crash, with 18 of them left orphaned. The crash of Flight 932 almost led to the discontinuation of the university’s football program. However, students and Thundering Herd football fans convinced the university President to reconsider and the school began rebuilding the program. They brought together a group of players who were on the junior varsity during the 1970 season, other students and athletes from other sports; many of these players had never attempted to play football before, and the team played on.

On November 12, 1972, the Memorial Fountain was dedicated at the campus entrance to the Memorial Student Center. Every year, on the anniversary of the crash, the fountain is shut off at the exact time of the crash, and not activated again until the following spring.