Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

15 Ways We Handle The Dead

Human beings, it would seem, have a fascination with death. While most of us would tend to agree that it is something best avoided, it also holds a sense of wonder for us. As the short story “The Body” by Stephen King (later made into the film Stand by Me) graphically illustrates, even as children, we are drawn by the allure of the dead. Just consider how many ways we have of saying that someone has died; Wikipedia counts at least 80, and there are doubtless dozens more.

But nowhere is our fascination with death exemplified as much as how we treat our dead. In most Western countries, death is celebrated with a (often solemn) ceremony, and the deceased is interred in a necropolis, a city of the dead (more colloquially known as a graveyard or cemetery). The burial site is often given a marker or memorial so the deceased may be remembered by future visitors to the site. Of course, funeral rites vary from place to place, but in most cases, great care and ceremony are involved.

Here I present (in no particular order) the 15 most common means of putting someone’s mortal remains to rest.

Aquamation is the most environment-friendly way of disposal of human bodies. The process involves the rapid disintegration of the human body into high quality fertilizers. In comparison with cremation, about 10% of the energy is used, and all of the associated pollution is avoided.

With Aquamation, an individual body is gently placed in a clean, stainless steel vessel. A combination of water flow, temperature (~90C) and alkalinity are used to accelerate the natural course of tissue hydrolysis. Typically the process takes about four hours to complete.

Burial is the act of interring a person or object in the ground, and is probably the simplest and most common method of disposing of a body.

Burial is generally accepted to be one of the earliest detectable forms of religious practice, and many hominid remains have been discovered interred with grave goods, or with obvious signs of ceremony. Even today, most burials are presided over by a religious figure, and in many cultures they are conducted with great reverence.

In some cultures, exactly how one is buried may make all the difference. Christian burials, for example, often demand that the body be laid flat, with arms and legs extended and aligned east-west, with the head at the western end of the grave. This is to allow them to view the coming of Christ on Judgment day. In Islam, the head is pointed toward and the face turned to Mecca. Warriors in some ancient cultures were interred upright, and an upside down position is typically symbolic of suicides, or as a punishment.

It is interesting to note that humans are not alone in their practice of burying the dead, either. Chimpanzees and elephants have been observed to cover dead family members with leaves and branches. An elephant that trampled a mother and child buried the remains under a pile of leaves.

Burial at sea is the term used for the procedure of disposing of human remains in the ocean. Many cultures have regulations to make burial at sea accessible, and it is fast becoming a popular choice. In the United States, ashes must be scattered no less than three nautical miles from the shore, and bodies given over to the sea must be buried in locations of at least 600 feet depth.

Traditionally, the service is conducted by the captain or commanding officer of the ship or aircraft. Possibilities include burial in a weighted casket, burial in an urn, being sewn into sailcloth or scattering the cremated remains. Burial at sea by aircraft is normally done only with cremated remains. It is also possible to have the ashes mixed with concrete to form an artificial reef. This gives the deceased a form of immortality by allowing their remains to contribute to an entire ecosystem.

Most major religions permit burial at sea, and some have very specific rituals concerning it. Islam and Judaism both prefer burials on land, but both have allowances for maritime burials, should the need (or desire) arise.

Entombment is the act of placing human remains in a structurally enclosed space, or burial chamber. This differs from burial in that the body is not consigned directly to the earth, but rather is kept within a specially designed sealed chamber. There are many different forms of tombs, from mausoleums (specifically built for this purpose), to elaborate (and often decorative) family crypts, to a simple cave with a sealed entrance. A mausoleum is typically an above-ground structure, but a tomb may also be an underground chamber.

Tombs may be designed for singular use, or may serve to house the remains of several generations. Individual remains within a tomb are often sealed in coffins or sarcophagi, though in some cases they are placed in interment niches. Tombs may belong to families, religious organizations or even entire cities. Catacombs, such as the famed Parisian catacombs, are a form of tomb (as well as a mass grave), and in some cases, as with the Capuchin Catacombs of Palmero, serve as macabre tourist attractions.

Dismemberment involves cutting, tearing, pulling, wrenching or otherwise removing, the limbs of some creature. It is typically committed after death, for a specific purpose, but on occasion has been the cause of death.

Until the late 19th Century, hanging, drawing and quartering was a common punishment for high treason. This involved the offender being dragged through the streets by a horse while tied to a hurdle, then being hanged by the neck until nearly dead (but certainly still alive), having the vital organs removed from the abdomen and burned in front of them (males were typically castrated at this time, as well, and their genitals also burned), then being decapitated and the body cut into four pieces. The head and pieces were then typically boiled and displayed as a warning to others. In the Netherlands and Belgium, those convicted of regicide had their arms and legs tied to horses and the abdomen sliced open.

In modern times, the most likely reasons for dismemberment are to hide the identity of the deceased, or to make the corpse more accessible for transport or fitting into tight spaces. Thus, it is typically performed postmortem. Because fingerprints, hair samples, facial modeling and toe prints can all be used to indicate identity, there are good reasons why many murderers take the extra time to do this.

Dismemberment has also been practiced in the past on the bodies of Catholic saints, as their earthly remains are considered to be holy relics.

Cremation is the process of reducing dead bodies to basic chemical compounds in the form of gases and bone fragments. This is most often performed in a crematorium, though some cultures, such as India, do practice open-air cremation. Generally, temperatures of no less than 1500oF are required to ensure complete disintegration.

After the process is complete, the dry bone fragments that remain are swept out of the retort (the chamber in which the body is immolated) and passed through a cremulator. This machine grinds the bones into a fine, sand-like powder.

In some cultures or regions, pulverization may be performed by hand. These “ashes” are then provided to the family to be kept, scattered or interred in a traditional grave.

In Japanese and Thai funeral traditions, the bones are not pulverized (unless requested by the deceased). Instead, family members sift through the remains and remove the bones with special chopsticks intended for this purpose. There is a great deal of ceremony involved in this process. The bones of the feet are picked first, with the bones of the head being placed in the urn last. This is done so that the deceased will not be upside down in the urn. The urn is then kept in a place of honor or a small shrine within the home.

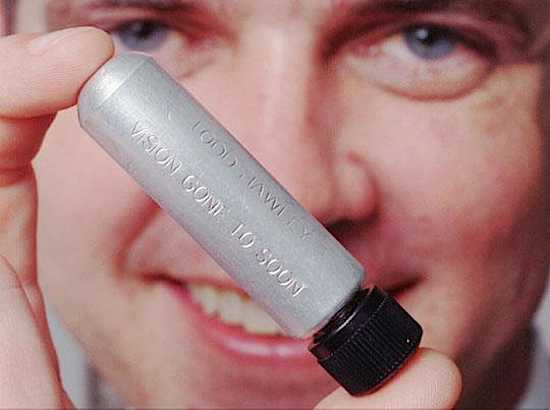

In the late years of the 20th Century, it became the vogue to be “buried in space,” that is, to have a small part of the cremated remains placed into a capsule (about the size of a tube of lipstick) and launched into space using a rocket. Since 2004, there have been about 150 space burials.

This option is not commonly chosen, as it can be quite expensive and only one company currently specializes in providing this service. In most cases, the remains are fired into Earth orbit, though some have been launched into other trajectories, including to the moon, Pluto, and deep space. Famous people who have been “buried” in space include James Doohan (“Scotty” of Star Trek fame), Gene Roddenberry (creator of the aforementioned Star Trek), Timothy Leary (American writer, psychologist, and drug campaigner), Clyde Tombaugh (American astronomer and discoverer of Pluto), Dr. Eugene Shoemaker (Astronomer and co-discoverer of the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9), and Leroy Gordon “Gordo” Cooper, Jr. (American astronaut and one of the original Mercury Seven pilots).

The Egyptians are perhaps the best-known adherents of this process (although they are far from the only ones), in which a corpse has its skin and organs preserved, by either intentional or incidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity or lack of air. The oldest mummy found to date was a decapitated head that dates back to 6000 BC. The earliest Egyptian mummy dates back to about 3300 BC.

The Egyptian mummification process is well-known to modern science, through opportunities to study mummies from that culture, and by means of references from Egyptian and other classical accounts, as well as paintings in tombs that demonstrate the process. In short, the internal organs are removed and dried out using natron, and are then placed either in canopic jars, or else made into four packages to be reinserted into the body cavity. The brain is scrambled by means of a hook run up through the nasal cavity, then pulled out through the nose and discarded. The heart was considered to be the organ associated with intelligence and life force.

The body cavity would then be washed out with spiced palm wine and filled with dry natron gum resin and vegetable matter. It was then placed in a bath of natron and left for as long as 70 days. This would dehydrate the body and better preserve the skin. The body cavity was then excavated and refilled with permanent stuffing, and, often, the viscera packages. The abdominal incision was closed, the nostrils plugged with wax, and the body anointed with oils and gum resins. The remains would then be wrapped in layers of linen bandages, between which amulets were inserted to guard the deceased from danger and evil.

But it is also possible for a body to undergo natural mummification. The extreme cold of a glacier in the Ötztal Alps resulted in the mummification of a hunter who lived about 5,300 years ago, now known as Ötzi the Iceman. Bog bodies, who were victims of murder or ritual sacrifice, are a common find in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland, Germany, Scandinavia Denmark.

Also known as anthropophagy, cannibalism has been recorded throughout history and continues to be practiced even today. Specifically, it is the act of humans eating other humans. If humans are specifically killed to be eaten, it is called homicidal cannibalism. If the practice is restricted to those already dead, it is called necro-cannibalism. There are two kinds of cannibalistic social behavior: endocannibalism (the act of consuming humans from the same community) and exocannibalism (eating humans from other communities).

Cannibalism may be practiced for a number of reasons. Among primitive peoples, it was often believed that consuming an individual’s flesh could grant their abilities to the cannibal. Cannibalism might also be performed simply because the cannibal enjoys the taste, as a form of insult to the dead, or to honor them.

Cannibalism has long served as a recurrent theme in myth and legend, dating back to Ancient Greece, with stories of Cronus, an elder god who was said to have devoured his children. Baba Yaga is a famous Russian cannibal, and the Brothers Grimm related the story of Hansel and Gretel, in which two young children, left in the woods to die by their parents, find a cottage made of cake and gingerbread. The building turns out to be the residence of a cannibalistic hag who enjoys the tender flesh of young children and plans to cook and eat the pair, but is slain by the cleverness of the children.

Cryonics is the low-temperature preservation of humans and animals who can no longer be sustained by contemporary medicine, with the hope that healing and resuscitation may be possible in the future. Because, in the United States, cryonics can only be legally performed on humans after they have been pronounced legally dead, procedures ideally begin within minutes of cardiac arrest and use cryoprotectants to prevent ice formation during cryopreservation. However, the idea of cryonics also includes the preservation of people after longer post-mortem delays because of the possibility that brain structures encoding memory and personality may still persist or be inferable. Whether sufficient brain information still exists for cryonics to work under some preservation conditions may be intrinsically unprovable by present knowledge. Most proponents of cryonics, therefore, see it as a speculative intervention with prospects for success that vary widely depending on circumstances.

Unfortunately, current methods are clumsy and far from perfect, and must be undertaken with the hope that a future society that can revive and cure the body might also be able to repair the damage done to cells and body structures by the freezing process. Certain chemicals can be utilized to offset the effects, but some of these are highly toxic and, unless purged from the body before revivication, the effort may be rendered pointless.

Dissolution is a tried-and-true favorite of those who really want to make certain that remains are never found: simply dissolve the body in a strong solvent, such as lye or hydrochloric acid. Unfortunately, it’s not quite that simple.

While boiling lye will definitely render a victim unrecognizable in a matter of a few hours, it doesn’t do the job completely. Bits of bone, teeth and any unnatural parts (such as pacemakers) are left behind. Even a single tooth can contain enough DNA to identify a victim and lead the police to your door. That is, if the strong smell of lye doesn’t alert them first. Such methods have been used in the United States for almost two decades, to dispose of animal carcasses. Now, it’s being considered as an alternative to burial.

The process is called alkaline hydrolysis and uses lye, 300-degree heat and 60 pounds of pressure per square inch to destroy bodies, using big stainless-steel cylinders that are similar to pressure cookers. A straining device catches things like teeth, bits of bone and the aforementioned inorganic entities. Bones and teeth are crushed to a fine powder and offered to the family in the same manner as ashes. The rest of the body turns into a viscous brown fluid with the consistency of motor oil and a strong smell of ammonia. This is simply washed down the drain.

Exposure is not typically practiced intentionally in the West today. More often, it results from an accident where someone dies in an isolated location and the body goes unnoticed for a period of time. However, there are people who dispose of bodies in this manner on a regular basis.

Tibetan sky burial (known as a jahtor ) is the ritual dissection of the body, which is then laid out for the animals or the elements to dispose of. Tibet is a mountainous land where the soil is too rocky to dig graves and there is a scarcity of fuel for cremation, so sky burial arose as a logical alternative. Here’s how it works:

After being sent on their way with ceremony, the remains of the deceased are toted up to a designated location, where the body is laid out (typically naked).

Then the rogyapas (body-breakers) go to work. Flesh is stripped from bones, limbs are hacked away and the whole is ground up and sometimes mixed with tsampa (a mixture of barley flour, tea, and yak butter or milk) and offered to the vultures (which have learned to keep watch on the traditional burial site). The rogyapas do not go about their task with somber ritual, but rather they laugh, joke and chat as in any other manual labor.

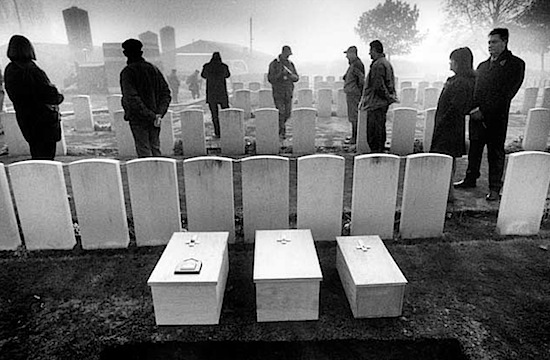

When expedience is an issue, as is often the case with a plague or a disaster, a mass grave may be used. A mass grave is simply a singular location in which multiple human remains are interred. Mass graves are common as a result of wars, plagues, famine and disasters, when health concerns become an issue and it would be unwise to wait for each body to be identified and given the proper rites. Mass burial is generally frowned upon because it detracts from the identity of the deceased.

Mass burial was once far more common than today, but the practice is hardly lost to modern people. Locations known to harbor mass graves include The Killing Fields of Cambodia, the Soviet Union, Chechnya, Iraq and even the United States. Hart Island is a potter’s field, a place intended for the burial of unknown or indigent people, for the city of New York. It is the largest tax-funded cemetery in the world and currently houses over 850,000 “residents,” dating as far back as the Civil War, and is still used even today.

Taxidermy is the act of mounting, or reproducing, dead animals for display (e.g. as hunting trophies) or for other sources of study. However, some people haven’t let that stop them from taking the next step to immortality and having themselves taxidermied after death. The process is rather simple, but requires a lot of skill. The animal is skinned and the innards disposed of (often without the taxidermist ever seeing any of the internal organs). The skin is tanned and then placed on a polyurethane form. Clay is used to install glass eyes. Forms and eyes are commercially available from a number of suppliers. If not, taxidermists carve or cast their own forms.

The legalities of the taxidermy of human beings escape me (I could find no specific references to them), but I would assume that the process is legal, if one makes all the proper arrangements and can find a taxidermist willing to take the job. However, the difficulties involved in such an enterprise have meant that few people have had the process done. One such individual, however, was philosopher Jeremy Bentham.

Born in Spitalfields, London, in 1748, Bentham was a prolific writer (he left manuscripts amounting to some 5,000,000 words) on the subject of law, equality between the sexes, animal rights, economics and utilitarianism. As specified in his will, Bentham’s body was dissected as part of a public anatomy lecture. Afterward, the skeleton and head were preserved and stored in a wooden cabinet called the “Auto-icon,” with the skeleton stuffed with hay and dressed in Bentham’s clothes. Originally kept by his disciple, Thomas Southwood Smith, it was acquired by University College London, in 1850. It is normally kept on public display at the end of the South Cloisters in the main building of the college, but for the 100th and 150th anniversaries of the college, it was brought to the meeting of the College Council, where it was listed as “present but not voting.”

As perhaps the ultimate bid for immortality, plastination is a technique used in anatomy to preserve bodies or body parts. The water and fat are replaced by certain plastics, yielding specimens that can be touched, do not smell or decay and even retain most properties of the original sample. The resultant plastinates can be manipulated and positioned as desired.

Plastinates are used as museum displays, as teaching tools and in anatomy studies. The process so perfectly preserves tissue, musculature and even nerve clusters that plastinates serve as invaluable references to the way our bodies (and those of other animals) work.

The process of plastination began in November, 1979, when Gunther von Hagens applied for a German patent, proposing the idea of preserving animal and vegetable tissues permanently by synthetic resin impregnation. Since then, von Hagens has applied for further U.S. patents regarding work on preserving biological tissues with polymers.