Religion

Religion  Religion

Religion  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Horrifying Final Destination-Like Accidents

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Music Biopics That Actually Got It Right

History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Religion

Religion 10 Innovations and Discoveries Made by Monks

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Horrifying Final Destination-Like Accidents

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Music Biopics That Actually Got It Right

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Momentous Events That Also Occurred on July 4th

Animals

Animals 10 Times Desperate Animals Asked People for Help… and Got It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Top 10 Worst Moments in US Baseball

This list examines and ranks moments in American professional baseball’s history we would all like to forget, some because of human folly, some because of terrible fate. Add your own favorites to the comments as always.

Everyone loves to see a person get really angry. It’s entertaining. But on 24 July 1983, with the Kansas City Royals playing the Yankees, Royal George Brett realized every kid’s dream of saving a game in the 9th inning by slamming a homer. It was a two-run bash that put the Royals up 5-4. As he crossed home and disappeared into the dugout, the home plate umpire, Tim McClelland, was alerted by Yankees manager Billy Martin that Brett’s bat might have more than 18 inches of pine tar on it, from the tip of the handle up.

More than 18 inches of any substance on the bat is a violation of the rules, and after several minutes of measuring the bat against the wide end of home plate, which is 17 inches, the three umpires agreed that Brett was in violation. McClelland then searched for him in the dugout, found him, and motioned that he was out. This is all televised and can be found on YouTube.

Brett immediately charged out of the dugout, so infuriated that his face was bright pink, bellowing profanity and raging at McClelland that he was going to kill him. The Royals manager, Dick Howser, and several of Brett’s teammates had to tackle him to keep him off McClelland, who also voided the home run and declared the game over and the Royals the losers.

A sports commentator quipped, “Brett has become the first player in history to hit a game-losing home run.” The Royals protested the ruling, and it was overturned because an illegal bat would necessitate the batter being called out, but that because pine tar did not assist the distance of a struck baseball, Brett’s home run would count. The game was ordered to be resumed from that point, and the Royals won, 5-4. Brett’s rampage did not exactly send a good message to his young fans.

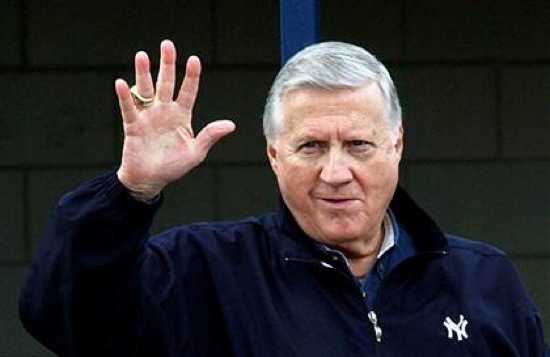

Steinbrenner was the majority owner of the New York Yankees from 1973 to his death in 2010 at the age of 80. During those 37 years, he made the players, coaches, assistant managers, and fans hate his guts. His nickname was “the Boss” which, by the bye, was also Josef Stalin’s nickname among other Soviets.

Among his more ridiculous tyrannies was forcing the players to shave their beards and keep their hair cut military-style. This was during the 70s and 80s, when The Big Hair was in. Players were allowed very thin mustaches if they wanted. He once told coach Yogi Berra to order Goose Gossage to shave his beard. Berra loathed Steinbrenner, and told him several times that the only reason he worked under Steinbrenner was because he loved the team, and that he did not need or care about the money. Steinbrenner immediately asked him if he wanted a raise, to which Berra answered, “Yeah. Sure.”

Gossage protested the demand by wearing his mustache in the style of Hulk Hogan, which was also against the Boss’s rules. Steinbrenner actually benched Don Mattingly, one of the Yankees’ best at the time, for refusing to cut his mullet. When this infuriated teammates and fans, Steinbrenner relented.

Steinbrenner attended a lavish baseball banquet once and met legendary pitcher Tom Seaver, who made no secret of his disdain for Steinbrenner, criticizing him right to his face. Steinbrenner exploded at him and threatened to fire him on the spot, to which Seaver replied, “I play for the Mets, George.” Steinbrenner snorted and walked off.

He seemed to maliciously enjoy firing people, because he fired managers over 20 times. The most famous of these is Billy Martin, whom Steinbrenner fired and rehired 5 times. The reason for Martin’s firing was always his outspoken criticism of the Boss, and for the Boss to retaliate by firing him every time made a very poor impression throughout the MLB: say one thing he didn’t like and you were gone. There was no margin for error and no possibility of pleasing Steinbrenner.

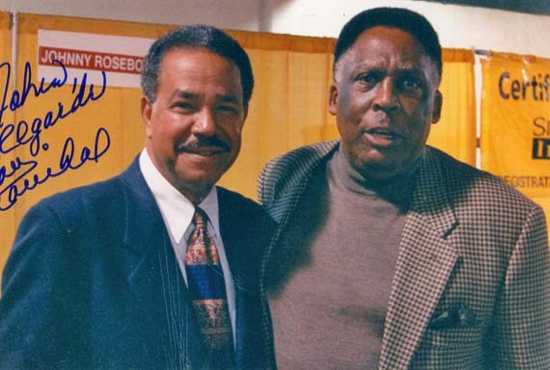

As far as “clearing the benches” goes, no professional incident showers quite such magnificent brutality and dishonor on the sport as the notorious spat between Juan Antonio Marichal Sanchez and John Junior Roseboro that took place on 22 August 1965. Marichal pitched for the San Francisco Giants; Roseboro caught for the Los Angeles Dodgers, and the two teams were (and are) arch rivals.

Twice in the 1st three innings, Marichal deliberately pitched so close to lead-off Maury Wills’s head that he had to duck, just to aggravate him. Roseboro decided to trash talk Marichal when he was up at the plate in the bottom of the 3rd. Marichal was already irritable at being shown up by opposing pitcher Sandy Koufax (more on him later), and he and Roseboro exchanged profanity at the plate, until Roseboro started returning Koufax’s pitches deliberately close to Marichal’s head.

Roseboro finally jumped up and got in Marichal’s face to yell, and Marichal simply backed up and smashed Roseboro in the head three times with his bat, knocking him down and opening a gushing gash in his scalp that required 14 stitches. This cleared both benches into a 15-minute, home plate brawl. Willie Mays of the Giants helped Roseboro back to his dugout while Koufax tried to stop it all. The most famous photograph of the fight shows Marichal with the bat reared over his head and Roseboro falling at his feet.

Marichal was given only 9 days suspension and a $1,750 fine, a very light punishment according to most critics. Roseboro recovered without a problem and the two became friends.

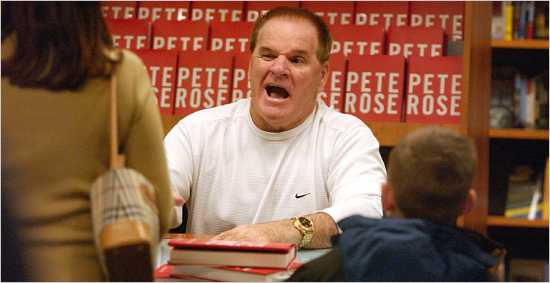

Rose played for the Cincinnati Reds from 1963 to 1986, and during that time, he accumulated more hits than anyone else in the history of MLB, 4,256. Ty Cobb had had the most hits for 57 years with 4,191 (Rose had 2624 more at-bats). They are still the only two players with over 4,000 hits. “Charlie Hustle” was one of the finest contact hitters in the history of the game. A contact hitter is so called because he regularly makes contact with the ball, but rarely puts home run power behind it. Cobb was also one of the greatest.

Rose was one of the finest all-round players ever, outstanding as a 1st, 2nd, and 3rd baseman, and a right and left fielder. He got his nickname for his fast base running and his zeal to win games. But frequently during his career, he gambled on himself to win and on his own team to win. He never bet that he or his team would lose. That would have amounted to throwing games. Instead, he knew his team was best and figured he could make a little extra money on the side. He didn’t see it as hurting anyone.

The problem was that he knew it was against MLB’s rules and that if discovered, he would face dire consequences. So when scrutiny came upon him, he lied about it. His fans generally agree that this dishonesty is the only qualm they have with him. He also did no good for his personal reputation when, in 1990, he pled guilty to income tax evasion. He went to prison for that, and his gambling addiction finally found mainstream coverage. He finally came clean in 2004, a long time to treat people like they’re stupid.

Nevertheless, by this point, there is even more shame on MLB, and the staff that votes for Hall of Fame inductees, for still refusing to allow such a superlative talent into the Hall of Fame. Its lack of forgiveness for mistakes dishonors the spirit of the game, just as Rose did. In the end, the Hall of Fame itself is tarnished for such an absence, since the Hall of Fame is supposed to honor talent and legacies. Like the Academy Awards, there should be no politics or decisions based on anything other than performance. But as with all voting awards, humans are the voters, and humans can be given to holding grudges.

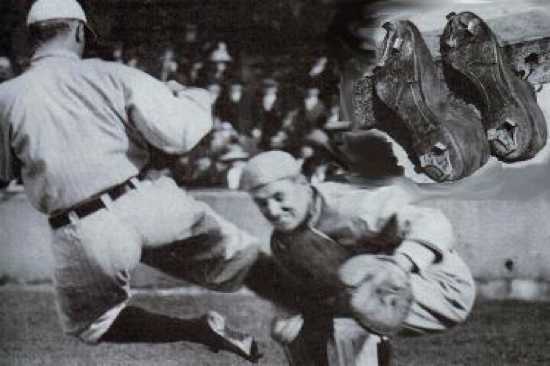

What would a pejorative baseball list be without Ty Cobb? He may be the greatest player ever. Hard to say. He still holds several hitting records after a whole century, including career batting average (.367), and most career batting titles (12). He scored 4,191 and stole home 54 times (with his freshly sharpened cleats aimed right at the catcher’s face). But in terms of personality, Cobb was a monster. He had a notoriously vicious, intemperate disposition, and was extremely racist, once slapping a black elevator operator for mouthing off to him, and even stabbing a black constable who tried to stop him.

He once knocked the Detroit Tigers’ groundskeeper’s teeth out for not raking his (the groundskeeper’s) footprints out of the infield before a game, then wrapped the groundskeeper’s wife up in a chokehold when she grabbed him. He and umpire Billy Evans once resolved to settle their extremely vulgar shouting match during a game by fists afterward. Cobb won the fight by beginning with a kick to Evans’s groin, then pinning him and punching him on the ground.

His worst moment, though, occurred on 15 May 1912, when a heckler named Claude Lueker insulted Cobb at the top of his voice for 6 full innings. Not a good idea. To his credit, Cobb tried to ignore him for 3 innings, calling on the opposing manager and two policemen to eject Lueker from the park, but no one did. Finally, at the end of the 6th inning, with Cobb walking back to the dugout, Lueker shouted, “You’re a half-nigger, Cobb!”

Cobb calmly tossed his hat into the dugout and climbed into the stands before anyone could stop him. Lueker was severely handicapped, with one hand and three fingers of the other hand missing from an industrial accident. Cobb punched him right in the face and when the crowd shouted that Lueker had no hands, Cobb roared, “I don’t give a damn if he got no feet!” and continued pummeling him until he was tackled by his own teammates.

He was suspended for the rest of the season, and his Tiger mates boycotted the next game in his defense. Cobb finally exhorted them to play the season out. He put Lueker in the hospital with a broken jaw and nose.

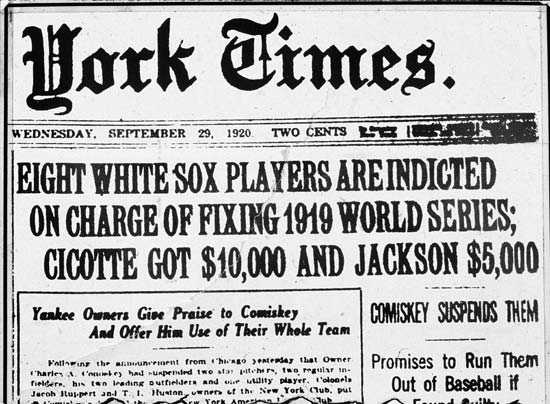

If you’re a baseball fan, you need no backstory to this. But for those who don’t know, the 1919 World Series was played between the Chicago White Sox (who were branded “Black Sox” for what they did) and the Cincinnati Reds. The White Sox were owned by Charles Comiskey, a tyrannical jerk who viewed the players as his property to do with as he liked. He made Ty Cobb look like Jesus Christ. Comiskey was, like all owners, allowed to pay his players whatever he felt like paying them, and under the MLB Reserve Clause, the players had no say in the matter.

Comiskey promised Eddie Cicotte, a pitcher, a $10,000 bonus if he could win 30 games. When Cicotte won his 28th, Comiskey benched him for the rest of the season to keep from paying up. Comiskey promised the whole team a bonus if they won the 1919 pennant. That bonus was a case of 12 bottles of flat champagne. He forced them to pay their own laundry bills for their uniforms.

Comiskey’s infuriating behavior toward the team caused at least 6 of them to conspire to throw the 1919 World Series to punish him. They were Eddie Cicotte, Arnold Gandil, Charles Risberg, Fred McMullin, Oscar Felsch, and Claude Williams. These 6 men, along with two others, were banned from professional baseball for life. The other two were George Weaver and “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, accused of knowing about the fix and doing nothing to stop it.

Today, history looks more kindly on Weaver, and much more kindly on Jackson. Jackson was illiterate and honestly had no direct knowledge of the fix. He may have safely assumed something was wrong after watching the 6 conspirators making ridiculous errors. Weaver knew what was up, but refused to rat out his friends. He and Jackson played magnificently throughout the series. Jackson is today remembered as one of the absolute finest hitters in history, 3rd in all-time career batting average with .356. In his rookie season of 1911, he hit .408.

The Reds won the series 5-3. Back then the series was of 9 games. The conspirators were great ballplayers but terrible actors, because in the games they decided to throw, even the batboys knew something was amiss. Cicotte, an outstanding pitcher, somehow gave up 5 runs in the 4th inning of the 1st game. This drew immediate suspicion. The Sox lost this game 9 to 1, a ridiculous score for such a fine team.

They lost the 2nd game, too. Dickie Kerr, a rookie pitcher, pitched a shutout in the third, proving he had nothing to do with the fix. Jackson, in the 4th game, attempted to throw a man out at the plate, but Cicotte deliberately caught and fumbled the ball to let him score. Jackson hit a monumental .375 for the series. By the time the series was over, there were more boos than cheers throughout the games. Had it not been, the following year, for a new star the fans could get behind, Babe Ruth, baseball might have died altogether because of this debacle. The 8 players listed above are still ineligible for the Hall of Fame.

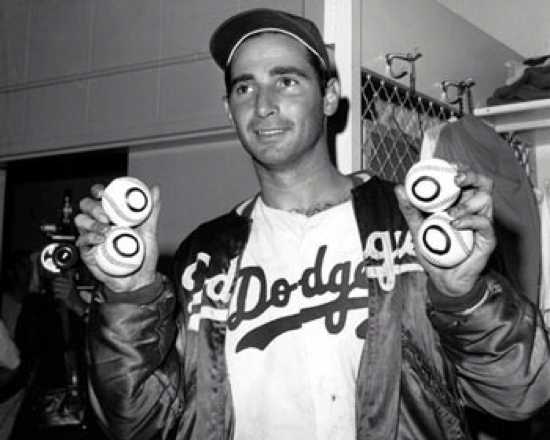

One of the saddest ends to what could have been universally accepted as the greatest pitching career in baseball history was the premature retirement, due to severe arthritis, of Sandy Koufax. He played for 12 years, always for the Brooklyn or Los Angeles Dodgers, and yet after those 12 short years, he had posted 2,396 strikeouts, and a career ERA of only 2.76, second lowest in the history of the live-ball era.

His best seasons were 1965 and 1966. For several years, he was pitching full 9 innings of game after game with horrible pain in his left arm, centered at the elbow. The morning after one of these games, he woke to find his arm black and blue from shoulder to wrist from hemorrhaging. To deal with the pain, he began taking Empiring with codeine every night, and sometimes during a game, Butazolidin, and applying a capsaicin cream to his elbow. After each game, he had to immerse his left arm in a tub of ice.

And still, he went out a pitched another complete game the next day, and again, and again. On 9 September 1965, in spite of his agony, he pitched a perfect game. More people have orbited the Moon than have pitched perfect baseball games. It is defined as no hits, walks, struck batters, or any base reached safely by the opposing team. 27 up, 27 down. Koufax’s perfect game also featured the most strikeouts, 14 out of 27.

His pitches were the stuff of legend. Carl Yastrzemski, who retired with 3,419 hits, remarked that “hitting the curveball off Sandy Koufax was like drinking coffee with a fork.” Koufax threw with a marked over-the-top arm motion, not out to the side. This, along with his extremely strong legs, gave him blazing speed with every pitch. His curveball was clocked at 94 mph. It curved from 12 o’clock to 6 o’clock all within the last half to one-third of the distance to the batter, forcing the batters to swing almost straight up, as if golfing, in order to hit it in its descent.

He threw a four-seam fastball that floated upward up to 4 times before reaching the catcher. All the while, his arm was hurting so badly that he began tipping his pitches, letting the batters know what he was about to throw as he wound up. Nevertheless, as Willie Mays put it, “I knew every pitch he was going to throw and still I couldn’t hit him.”

At the end of 1966, with a 1.73 ERA in the books, he had to call it quits. He couldn’t sleep because of the pain, and considered having his arm amputated. Once he gave up pitching, however, his arm quickly healed. Jeff Torborg, who caught his perfect game, once remarked, “It’s like God came and took his arm back.”

The phrase that has been thrown around quite a lot during this ongoing scandal is, “The Babe did it on hotdogs and beer.” A lot of people hate to see a decades-old record broken, because they get used to the number involved. The most famous home run number is “60,” ever since Ruth hit that many in a season. Maris broke it 34 years later by just one run. But then, 37 years later in 1998, both Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa surpassed this record in a race against each other. Sosa finished with 66, McGwire with the magic 70.

It seemed too good to be true that not one, but two players could bring down such a hallowed record simultaneously. Then Sosa was caught using a corked bat, which is said to enhance swinging speed. His career would never recover. Then, in 2005, steroids hit the major news media so hard that Congress subpoenaed McGwire, Jose Canseco, and Rafael Palmeiro, three power hitters, to testify under oath. Sosa was discovered to have been using steroids. Canseco admitted to using them and personally injecting Palmeiro, who vehemently denied ever using them. Only months later, he was caught using them. He had lied to Congress and the fans. McGwire simply took the 5th on every question, but 5 years later he came clean and admitted to using them for years to overcome injuries. He claimed they had nothing to do with his home runs, which is obviously false, since all steroids enhance physical strength.

The scandal still hasn’t gone away, and probably never will, since the records remain in the books, and the two most hallowed hitting records, single-season and career home runs, are now both held by Barry Bonds, who has himself been convicted of obstructing justice in the steroids scandal, and is widely believed, though not yet confirmed, to have used them many times throughout his career. After he broke both records, with 73 homers in the 2001 season, and a career 762 homers in 2007, it was expected that he would remain an active player for years afterward, but the SF Giants refuse to renew his contract, and no other team would buy him, the truest testament to public opinion of him.

Mathewson was one of the mightiest pitchers in baseball’s history. His whole career fell within the dead ball era, when a single ball was used for the entire game. Such balls were difficult to see after they were covered in infield dirt and tobacco spit (spitballs were legal until 1921). Mathewson was no stranger to the spitball, but he was known as a “control pitcher,” as opposed to a power pitcher like Nolan Ryan. Whereas, Ryan could heave a 100+ mph fastball, he isn’t renowned for his skill at any other pitch, and had quite a few wild ones.

Mathewson, however, could throw strikes with everything. You name it: the 2-seam fast, the 4-seam, the forkball, slider, sinker, curve, knuckle, knuckle-curve, palm, palm-curve, and his money pitch, the screwball, which curves in the opposite direction of the curveball. Mathewson could fling them all right into the strike zone and fan anyone.

Consider that, whereas Nolan Ryan scored the most career strikeouts at 5,714, 839 more than 2nd place, he also scored the most walks with 2,795. Thus he walked about 49% of the batters he faced throughout his career. Mathewson, on the other hand, struck out 2,507 batters, while he walked only 848, which is 33% of them. That’s a gargantuan margin of difference between two greats and serves to show the accuracy of “the Christian Gentleman.”

Unfortunately, he was stolen too early from baseball’s posterity, when, in 1918, he enlisted into WWI as a chemical weapons trainer for the infantry. Ty Cobb and George Sisler also enlisted into the same unit, and the three saw each other frequently in France. As a captain, Mathewson’s job was to oversee the training, in gas chambers, of controlled release of mustard gas amid soldiers wearing their gas masks.

His voice inside the chamber was misunderstood by the gas operator outside as the order to release the gas. Once they heard the hiss, Mathewson first saw to the soldiers’ safety by ordering their masks on immediately. Only then, when milliseconds were precious, did he shout for the gas to be turned off. The operator did so, but there was a delay of more time than Mathewson could hold his breath. One private attempted to remove his mask, but Mathewson, with his eyes shut tight, knowing the sound of a mask being removed or put on, quickly yanked the man’s hands from his face and shouted for him to remain still.

Mathewson finally had to take a breath or risk blacking out. That single breath before the room was purged gave him tuberculosis. He tried coaching for a while when he returned the next year, but had to take frequent vacations for his lungs’ health, before finally retiring in 1921. He died 4 years later at 45 years old. His teammates openly wept at the first game following his death.

Lou Gehrig has the persistent misfortune to remain in Babe Ruth’s shadow as a power hitter. Gehrig hit his stride in 1926, his third season as a professional, in which he scored 20 triples, 47 doubles, 16 home runs, 116 RBIs, and an average of .313. Ruth posted much better home run and batting average scores, but if there was any ignoring that Lou Gehrig had joined him in the ranks of power hitting, he shattered that illusion the next year.

The 1927 Yankees remain, in most opinions, the finest professional baseball team in history. Ruth did himself proud by slamming 60 home runs to Gehrig’s “mere” 47, but Gehrig outpointed him in RBIs at 175, especially impressive given that Ruth batted 3rd and Gehrig 4th, and thus the bases were frequently emptied right before “the Iron Horse” stepped up. The Yankees’ line-up that season featured “Murderers’ Row”: Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri.

Combs and Koenig were outstanding contact hitters and routinely on base to be batted in by the next two. Gehrig’s position as 4th is why he still holds the career grand slam record of 23. His average that season was .373, by far the highest of the team, with Ruth and Combs at .356 (still stellar).

Late in his career, Gehrig, generally considered the finest 1st baseman in history, began having trouble making easy put-outs at 1st. He had run the bases like lightning for years but now only trotted, and slid very clumsily. He tripped over bases, and most obvious, by late 1938, his hitting power was noticeably diminished. He could make contact but somehow couldn’t manage home runs as well.

Everyone knew he was not guilty of partying and bingeing like his recently retired friend, Babe. This was not in Gehrig’s nature. By April 1939, he was posting his very worst scores ever. Only a .143 average with 1 RBI. Commentators remarked that he was hitting the ball on a regular basis like always, but the ball wasn’t going anywhere.

It was 2 May of that year when he finally broke his consecutive games streak of 2,130, a record that stood until 1995. Gerig walked up to the coach and said, “I’m benching myself, Joe.” He saw that he was only hindering the team and couldn’t do anything anymore.

His wife and he finally flew to the Mayo Clinic, where, after 6 days of testing, Dr. Charles Mayo himself wept as he read Eleanor Gehrig the diagnosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It causes the brain’s motor functions to deteriorate over several years or even decades, such that the victim tries to run or walk or stand up but gets slower and weaker without any impairment to the brain. The brain slowly loses its ability to communicate with muscles all over the body. There is almost never any pain at all, and for an athlete, seemingly no good reason for the bad performance.

Gehrig’s farewell, on 4 July 1939, between the games of a doubleheader, remains what most consider the most painfully bittersweet moment in the history of baseball. Gehrig was showered with gifts from teammates, rival players, coaches, managers, owners, and fans, which he took and quickly set down on the infield because he was too weak to hold them.

After Babe Ruth said a few words, Gehrig addressed the crowd of 61,808 in Yankee Stadium and told them not to feel bad for him, that he was “the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” His number 4 uniform was the first to be retired by any team in MLB history. In December of that year, he became the youngest inductee in to the Hall of Fame at the age of 36 (Sandy Koufax remains the record-holder today). He received the most votes for a position on the All-Century Dream Team in 1999.

He died 1 and a half years later on 2 June 1941 at his home, due to asphyxia from the ultimate paralysis of his diaphragm and abdominal muscles. Many sports writers and experts are of the opinion that had he played a long career of 20-25 years, instead of just 16, he would have surpassed many of Babe Ruth’s hitting records.