History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

8 Worst Cases of Friendly Fire

Friendly fire has been a part of warfare as long as it has existed. However, in more recent times, the growing destructiveness of modern weapons has contributed to making friendly fire more devastating than ever before. Despite the concurrent advance of IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) technology and other gadgets to reduce the likelihood of this, simple human error means friendly fire is a problem that is unlikely to disappear. This list looks at eight modern examples of friendly fire – their causes, and their consequences.

On 28 March 2003, during the Iraq Invasion, four British armored vehicles were carrying out forward reconnaissance when they were spotted by two A-10 Thunderbolt II ground attack aircraft. The American pilots spotted the orange air recognition panels on the vehicles, but misidentified them as being “orange rockets” on enemy vehicles. After confirming with a Ground Forward Air Controller (GFAC) that they were clear of friendly forces, the aircraft strafed the vehicles twice. Two Scimitar light tanks were destroyed in the attack – five British soldiers were wounded, and one killed.

A British inquest into the incident came to a number of conclusions about the cause of the incident, including the fact that the A-10s had not passed on the fact they had spotted the British patrol to the GFAC, nor did the aircraft receive clearance to engage from him. A US Air Force investigation recommended disciplinary action against both pilots, but both pilots where then later cleared of wrongdoing.

Two American F-16s were returning to base after a patrol in Afghanistan on April 17, 2002, when they reported coming under surface-to-air fire. Major Harry Schmidt (who was piloting one of the fighters) requested permission to open fire in response with his 20mm cannon. He received the order to “stand by,” and then less than two minutes later “hold fire.” Just seconds later, Schmidt declared he was “rolling in, in self-defense.” and dropped a 500lb laser guided bomb. After the strike, he remarked “I hope I did the right thing.”

The firing seen was actually from a firing range at Tarnak Farm, where Canadian soldiers were practicing firing at ground targets. Four Canadian soldiers were killed, and a further eight wounded. In 2004, Harry Schmidt was cleared of negligent manslaughter, but found guilty of dereliction of duty. His defense was that he believed that the firing posed a threat to him and his flight lead, so it was his right to attack in self-defense. He was fined $5700 and reprimanded.

In the wake of the First Gulf War, many Kurds in north and south Iraq rebelled openly against the Iraqi government. Operation Provide Comfort (OPC) was announced to establish a no-fly zone in order to protect Kurdish refugees from government persecution, and to provide humanitarian relief. On April 14 1994, 2 US Army Blackhawk helicopters carrying 26 crew and passengers entered the no-fly zone headed for the OPC military coordination center. They were intercepted by 2 US Air Force F-15s patrolling the no-fly zone. The Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) systems aboard the helicopters failed, causing them not to show up as friendly to the fighters.

The F-15s closed to make a Visual Identification (VID) pass. The first fighter reported “Tally 2 Hinds.” “Hind” is the NATO reporting name for the Mil Mi-24 helicopter gunship – a type that was known to be operated by Iraq. Following this, both F-15s circled back and shot down the two helicopters with air-to-air missiles. There were no survivors from the shoot down. A US Air Force investigation placed blame on several factors including the misidentification of the helicopters as “Hinds,” the failure of a nearby AWACS surveillance aircraft to intervene, the failure of the IFF systems, and the failure of the US Air Force to integrate US Army helicopters into its operations.

Exercise Tiger was a training exercise designed to simulate the D-day landings which would take place later that year. As part of the rehearsal, on April 28 1944, eight LSTs (Landing Ship, Tank) escorted by a corvette sailed into Lyme Bay in order to practice landing troops. The convoy was spotted by nine patrolling German torpedo boats (or E-boats) which immediately attacked the transports with torpedoes and guns. LST-507 and LST-531 were both sunk with the loss of more than 600 American lives.

Despite this, the exercise continued with the survivors being landed on the beach. As part of the exercise, a British cruiser shelled the beach with live ammunition as General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, felt that the men must be hardened by exposure to real battle conditions. However, this resulted in a further 308 American dead from friendly fire when troops strayed onto the wrong areas of the beach, straight into where the rounds were exploding.

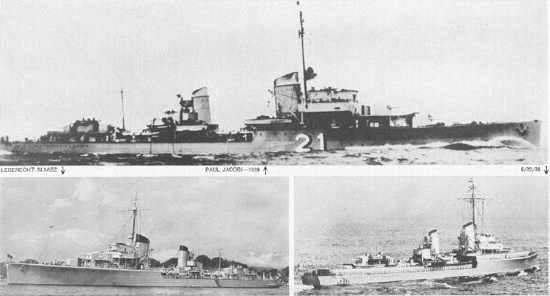

On February 19 1940, six German destroyers were sent to intercept a number of suspicious British fishing vessels off the Dogger Bank. The destroyers were sailing through a cleared channel between German minefields when a German bomber passed over the flotilla. The plane made no recognition signals, so the ships assumed it was a British reconnaissance plane and opened fire. This was enough to convince the bomber crew the ships were hostile, so the plane made two bombing runs, sinking the destroyer Leberecht Maass.

As the surviving ships moved in to recover survivors, Max Schultz then exploded and sank after hitting either a British or German mine. Chaos broke out as the rest of the destroyers dashed back and forth between erroneous reports of air and submarine attack. Theodor Riedel began dropping depth charges, the explosions of which jammed her rudder. After half an hour of confusion and mayhem, the surviving ships were ordered to return home. 578 German sailors died in total.

After the successful landings in France on D-day, Allied advances had been painfully slow against determined German resistance. Operation Cobra was intended as a breakout from this beachhead, and was to be preceded by a massive air bombardment. On July 24 1944, the first wave of heavy bombers took off, but heavy cloud caused the operation to be postponed for one day. However, the message did not reach all of the aircraft. 300 bombers flew in, dropping bombs down the Saint-Lô–Periers road rather than across it. Bombs hit American and German positions alike on either side of the road, killing or injuring 156 Americans.

The next day, Cobra started for real – 3000 fighter-bombers and heavy bombers dropped 4000 tons of bombs which obliterated the elite German Panzer Lehr Division. Once again, bombs hit American positions, causing 601 casualties. Among the dead was Lieutenant General Lesley McNair, the highest ranking American soldier to be killed in Europe. Nevertheless, Operation Cobra was a decisive Allied success, causing German resistance to rapidly collapse in France.

The first effective use of poison gas by German troops in April 1915 left the British Army scrabbling to find a way to retaliate in kind using chemical weapons. The Special Brigade was formed consisting of civilian technical experts and experienced front line soldiers to deploy the new weapon.

They first saw action at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, where they opened 5,500 cylinders of chlorine, releasing 140 tons of gas and relying on the wind to blow it towards German lines. However, a sudden shift in the wind direction led to chlorine gas being blown back across the British trenches. In addition, retaliatory German artillery fire hit and burst further cylinders of gas, releasing them in the British lines. The chlorine killed ten men, and injured approximately 2000 more British soldiers. Later on in World War I, both sides would progress to using poison gas shells fired from artillery guns to prevent any more such incidents.

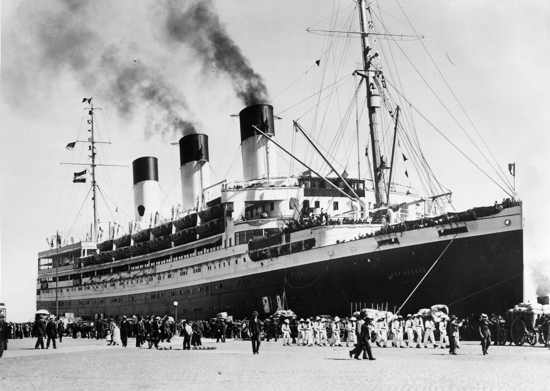

On May 3, 1945 (only one day before Germany’s surrender), the German transport ships Cap Arcona, Thielbek, and Deutschland came under attack by Typhoon fighter-bombers of the RAF. All three ships were sunk in the Baltic Sea by bombs, rockets and cannon fire. Unbeknown to the pilots however, was that the ships actually contained concentration camp survivors as well as Allied Prisoners of War. Many of the SS guards on board the ships were rescued by German trawlers, but the prisoners were left on board the sinking ships, while other survivors were shot as they swam ashore. It is estimated that almost 10,000 concentration camp survivors were killed in the attack.

![10 Worst Massacres Of African-Americans [DISTURBING IMAGES] 10 Worst Massacres Of African-Americans [DISTURBING IMAGES]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/vote-150x150.jpg)