Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Hilarious (and Totally Wrong) Misconceptions About Childbirth

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

10 Strange Civil War Weapons

The American Civil War (1861-1865) occurred during an age of Industrial Revolution, when some of history’s wackiest inventions were made. It’s no surprise creative geniuses of the day tried to come up with outside-the-box methods of killing the enemy. All of the 10 strange weapons on this list were available to US and/or Confederate soldiers.

Allegedly capable of flinging 300 rounds of ammunition per minute from its steam powered revolving drum for 100 yards, this centrifugal gun came into prominence during the 1861 Baltimore Riots. Although erroneously linked to industrialist Ross Winans, the 5-ton gun was actually invented and built by Charles S. Dickenson, who had brought his working model to Baltimore, Maryland to give a demonstration to the City Council. When violence and riots broke out in Baltimore between secessionists and the US government, and the city feared invasion by federal forces, the gun was commandeered by the police. After the crisis ended, Dickenson tried to smuggle the gun out of Baltimore, but it was captured by federal troops and eventually ended up displayed as a war prize in Massachusetts. The Mythbusters tested a similar steam machine gun contraption, you can watch the video above.

An attempt to create a multi-shot pistol by adding a horizontal magazine—some variations held up to 10 percussion cap or pinfire cartridges—the harmonica gun was probably invented and certainly patented by a Frenchman, J. Jarre of Paris, between 1859-1862. No musical instruments were involved. The name came from the shape of the magazine, and the weapon was also called the “slide gun.” An early manufacturer in the US was Jonathan Browning, father of firearms designer John Moses Browning. While looking like the sort of weapon a steampunk James Bond might carry, the harmonica gun proved too impractical for wide adoption. The user had to manually adjust the sliding magazine to center each cartridge under the hammer for every shot. Like VHS vs. Betamax, the much easier and faster shooting revolver finally won the day. The mechanism wasn’t limited to pistols—famed Texas Senator Sam Houston owned a percussion rifle (by Henry Gross) using a harmonica slide which is on display at the National Museum of American History.

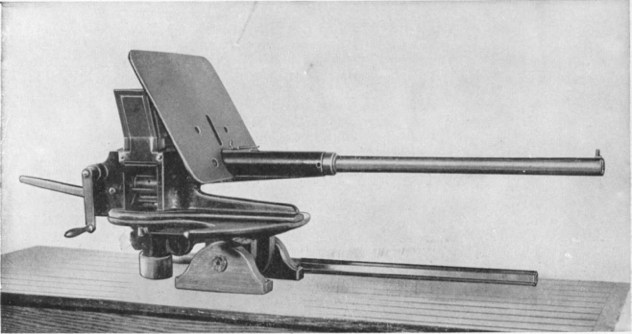

Many people have heard of the Gatling gun. The “devil’s coffee mill,” “coffee grinder” gun, “army in a box” or Agar gun was a similar hand-cranked machine gun firing .58 caliber cartridges at 120 rounds per minute. Having seen a demonstration in 1861, President Abraham Lincoln is said to have been quite enamored with the weapon. The US War Department ultimately acquired a total of 60 coffee mill guns. However, field commanders thought they wasted too much precious ammunition. The single barrel became quickly overheated during use, and the hopper-fed cartridges often jammed, making the guns impractical. Due to these problems, the guns saw little action during the war. A few were deployed to guard potentially vulnerable targets like bridges.

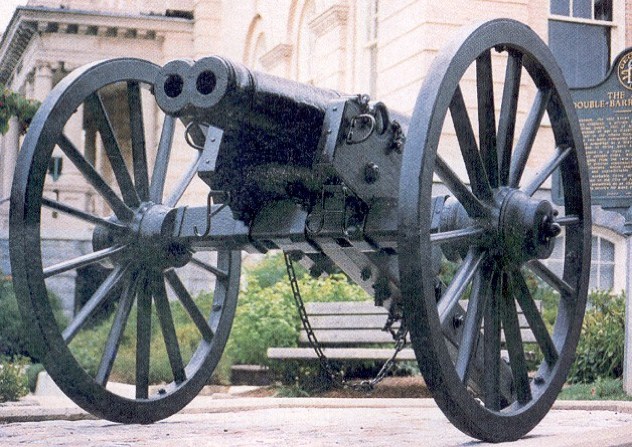

By joining two separate cannon barrels, the 1862 designer of this oddity, now a landmark in Athens, Georgia, believed the 6-pounder weapon capable of firing a devastating round of chain-shot—two cannonballs connected by a length of chain. The idea was both barrels would fire simultaneously, sending the chain-shot hurtling among enemy combatants. Unfortunately, the first field test of the prototype proved a disaster. The barrels did not fire at exactly the same time, causing the chain-shot to fly wildly off target or the chain to break. Regardless, the gun was kept by the city to use as a defensive weapon during the war, though it never saw action. The American Guns team recreated the double-barrel cannon on this episode. The idea certainly wasn’t new—in the 17th century English Civil War, a double-barrel cannon named Elizabeth-Henry belonged to the Earl of Northhampton’s regiment.

Dating from antiquity, the pike is a two-handed infantry weapon consisting of a wooden shaft about 6-10 feet in length tipped with a sharp steel point. In an age of gunpowder and projectile weapons, one might assume the pike was obsolete. However, due to the Confederacy’s difficulty manufacturing or importing guns, cheaper and easier to make pikes were sometimes distributed to soldiers. Most were the standard model, but a few had specialized blades. In 1862, Georgia Governor Joe Brown ordered 10,000 pikes to arm local troops—some topped with three blades in a cloverleaf pattern and others with a retractable spring-loaded blade. The South Carolina Confederate Relic Room and Military Museum has an example of a “Joe Brown’s pike.” You can view the video above. Needless to say, soldiers didn’t exactly embrace the pike, not when they were facing US troops armed with rifles.

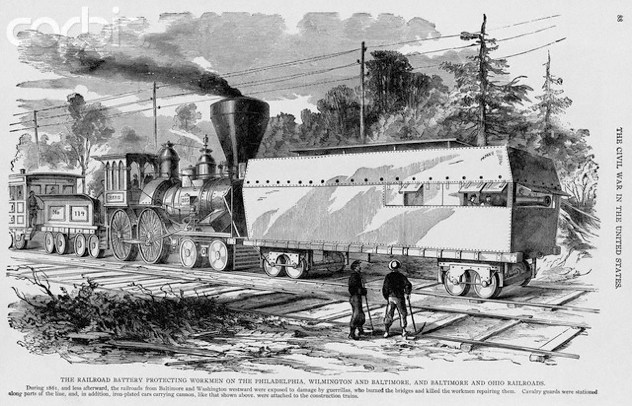

To defend railway bridges against Confederate attacks and saboteurs, the US government ordered experimental armored railroad cars (also called “ironclads” or an “ironclad battery”): baggage cars or boxcars fitted with thick iron sheets on the top and sides, and hooked to the front and behind a locomotive. Portholes in the sides and front/rear of the car allowed the fifty armed men inside to return fire, or aim a small cannon or pivot gun at the enemy. At least a few different models were made, including a variation consisting of a flat car with an iron shell built over it. In 1864, a lucky Confederate cannon shot destroyed an armored railroad car. Another was struck by a shell in 1865, causing injuries to the men inside. Some were captured by Confederate troops.

In the 19th century, a “torpedo” meant any kind of bomb, so the “coal torpedo” designed by Thomas Courtenay in 1864 was exactly as advertised—a gunpowder bomb disguised by genuine pieces of anthracite coal and deployed as a weapon of sabotage by the Confederacy’s Secret Service Corps against steam powered Union vessels. The bombs were loaded or smuggled into coal supplies in ships. When workers stoked the furnace, the bombs exploded. Two ships are known to have been damaged by coal torpedo detonations. Another sabotage attempt was made against the Springfield Armory by putting a timing fuse on a coal torpedo, but the bomb was discovered in time. Broader use of the coal torpedo came about after the war, when ship owners committed insurance fraud by blowing up their own vessels. A variation of the coal torpedo loaded with plastic explosives was employed in WWII.

Greek fire, the legendary weapon of the ancient world, was revived during the Civil War. For example, the failed Confederate sabotage plot to burn New York City with incendiary devices failed in part because most of the conspirators were unfamiliar with the Greek fire-fueled fuses. At the start of the war, Levi Short, a Philadelphia inventor, approached President Abraham Lincoln and demonstrated his new device: a rocket using his patented “solidified Greek fire.” While Lincoln wasn’t very impressed by Short’s demonstration, US Rear Admiral David Porter ordered 10 gross for his Mississippi River ships to try out in action against Vicksburg. The rockets performed as advertised—parts of the city went up in flames, but the fires didn’t last long—the chemicals burned about 7 minutes—not enough to do much damage. Porter deemed the invention “a humbug.”

Greek fire, the legendary weapon of the ancient world, was revived during the Civil War. For example, the failed Confederate sabotage plot to burn New York City with incendiary devices failed in part because most of the conspirators were unfamiliar with the Greek fire-fueled fuses. At the start of the war, Levi Short, a Philadelphia inventor, approached President Abraham Lincoln and demonstrated his new device: a rocket using his patented “solidified Greek fire.” While Lincoln wasn’t very impressed by Short’s demonstration, US Rear Admiral David Porter ordered 10 gross for his Mississippi River ships to try out in action against Vicksburg. The rockets performed as advertised—parts of the city went up in flames, but the fires didn’t last long—the chemicals burned about 7 minutes—not enough to do much damage. Porter deemed the invention “a humbug.”

Or the “many-chambered-cylinder firearm”—an unsuccessful 1850s attempt by T.P. Porter (no relation to #3) to upgrade the single-shot gun. The turret rifle’s concept seems feasible: rounds of .48 caliber ammunition were placed in a wheel-shaped 9-round magazine, and as each shot was fired, the wheel rotated to place the next round into position. Unfortunately, in practice that meant for every bullet aimed forward toward the enemy, another bullet was aimed backward at the shooter. This made users nervous and the weapon didn’t quite catch on in the general population, but personal weapons like these were carried by Civil War soldiers. Another variation sported a magazine holding 30 balls, gunpowder, and percussion caps. Rotating the turret loaded each chamber, ready for firing. Of course, a misfire or stray spark would make the whole magazine explode in the shooter’s hand.

In 1862, the US Navy launched its first submarine, the 47-foot long USS Alligator. Designed by French inventor Brutus de Villeroi, whose own government declined to build his marvelous machine, the Alligator was called a “submersible warship” and employed some cutting edge technology for its time, including an air purifying system and a lockout chamber allowing a diver to be deployed outside the submerged vessel. The US government kept the project top secret, intending to use it against Confederate ironclads. Alligator’s first mission on the Appomattox River was a failure as the water wasn’t deep enough. The sub was taken to the Navy Yard in Washington to be outfitted with a screw propeller. As Alligator was being towed to its next assignment (Charleston, South Carolina) when a huge storm forced the tow ship to cut the rope. Alligator sank to the bottom of the Graveyard of Ships off Cape Hatteras.