History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Groundbreaking Women Scientists Written Off By History

Outside of Marie Curie, how many other famous female scientists can you name? What were their discoveries? For most, the answer is not very many. Women have been very underrepresented in the world of science and this is not to say that it’s because they haven’t made any discoveries, but more so the fact that their discoveries have remained all but forgotten due to their male counterparts.

While sexism in science isn’t as large of an issue today, many female scientists in the past were not given the credit they deserved for their truly groundbreaking discoveries: making observations, proposing hypotheses, testing experiments, and putting in the hard work only to have their fame stripped away because of their sex.

10 Vera Rubin

b. 1928

Vera Rubin’s scientific career has been filled with criticism and hostility by her male colleagues, though she remains focused on her work rather than the politics of it all. Her first taste of hostility came when she had informed her high school physics professor that she’d been accepted into Vassar. He not so encouragingly replied, “That’s great. As long as you stay away from science, it should be okay.”

This didn’t discourage Rubin, however, and after being turned down from the astronomy program at Princeton because they didn’t allow women, Rubin went on to eventually earn her PhD at Georgetown. Working with her partner, Kent Ford, Rubin was the first to make the observation that stars on the outlying parts of galaxies had an orbiting speed matching that of the stars in the center of the galaxy. This was a very odd observation at the time because it was thought that if the strongest gravitational forces existed where the most mass was (in the center), the force should decrease farther out, causing the orbits to slow.

Her observations had confirmed a hypothesis made earlier by a man named Fritz Zwicky that said some sort of invisible dark matter must be scattered throughout the universe keeping their orbitals up to speed. Rubin was able to prove that 10 times more dark matter existed in the universe than previously thought, with up to 90 percent of the universe being filled with it. For years, Rubin’s observation failed to receive support, as many of her male colleagues discredited it. They felt her discoveries were impossible under Newtonian Laws and that she must have made a miscalculation. Both her doctoral and master’s thesis were criticized and basically ignored, though the evidence was irrefutable. Fortunately, the scientific community has since recognized her work, but only because her male colleagues later validated it. Rubin has yet to receive a Nobel Prize for her work.

9 Cecilia Payne

1900–1979

Cecilia Payne is a female scientist who came from a background of hard work, only to have her amazing discoveries discredited by her male superiors at the time. She began her studies at Cambridge University in 1919 after being given a scholarship for botany, physics, and chemistry. Her courses were seemingly completed in vain since Cambridge didn’t even offer degrees to women at the time. While at Cambridge, Payne did discover her love of astronomy. She transferred to Radcliffe and became the first woman to earn a PhD in astronomy there, while many began to take note of her astronomical brilliance.

After publishing six papers and earning her doctorate by 25, her biggest contribution to science was the discovery of what elements made up stars. Now I don’t know about you, but I think the ingredients of the stars are a pretty big deal . . . her male colleagues apparently did not think so. A man named Henry Norris Russell, who was in charge of reviewing Payne’s astonishing work, strongly persuaded her not to publish the article. His reasoning was that it was to contradictory to the standard knowledge of the time, and it wouldn’t be accepted. Interestingly, he did seem to have a change of heart four years later when he miraculously concluded what particles the sun was made up of and had his own papers published. Though his methods weren’t the same as Payne’s, his conclusion was, and he was given full credit for the discovery of the sun’s composition. From then on, Cecilia was basically stamped out of the history books. In another ironic twist, Payne had the “honor” of later being awarded with the Henry Norris Russell Prize for her contributions to astronomy.

8 Chien Shiung Wu

1912–1997

Chien Shiung Wu was a Chinese immigrant to America, where she began her work with the Manhattan Project and the development of the atomic bomb. Her biggest contribution to the world of science was a discovery that overturned a widely accepted law at the time. In science, “laws” are the most widely accepted and replicated observations in existence; so proving a scientific law wrong is a pretty big deal. The law was known as the Principle of Conservation of Parity, which is basically a very complicated way of proving the idea of symmetry, where particles that are mirror images of each other will act in identical ways.

Wu’s colleagues, Chen Ning Yang and Tsung Dao Lee, proposed a theory that this law could be disproven and approached Wu to help them prove their theory. Wu accepted their offer and carried out several experiments using cobalt-60 that proved the law wrong. Her experiments were incredibly significant in that she was able to show that one particle was more likely to eject an electron than the other and they were therefore not symmetrical. Her observation had overturned a 30-year belief and shattered the conservation of parity law. Yang and Lee of course didn’t record her observation and instead went on to win a Nobel Prize for their “discovery” that the conservation of parity was incorrect. Wu was given no mention, though it was her experiment that truly disproved the law.

7 Nettie Stevens

1862–1912

If you don’t know a lot about chromosomes, you should at least know that our sex is determined by our 23rd pair of chromosomes, the X and Y. Who is credited for this huge biological discovery? Well, most textbooks would point you to a man named Thomas Morgan, though the discovery actually goes to a female scientist by the name of Nettie Stevens. She studied sex determination in mealworms and soon realized that it depended on the X and Y chromosomes. While she was recognized as working with a man named Thomas Morgan, nearly all of her observations were made independently.

Morgan was later credited with the Nobel Prize for Nettie’s hard work. To add insult to injury, he later posted an article in the journal Science saying that Stevens acted as more of a technician than an actual scientist throughout the whole experiment, though this was found to be quite untrue.

6 Ida Tacke

1896–1978

Ida Tacke made huge advancements in the fields of both chemistry and atomic physics that were basically ignored until they were later “rediscovered” by her male colleagues. First, she managed to find two new elements, rhenium (75) and masurium (43), that Mendeleev predicted would be on the periodic table. While she is credited with the discovery of rhenium, you may notice that there is no such element known as masurium at atomic number 43 or anywhere else on the current periodic table. Well, this is because it’s now known as technetium, the discovery of which is credited to Carlo Perrier and Emilio Segre.

During the time of the first observation, Tacke’s male colleagues felt that the element was too rare and disappeared too quickly to be found naturally on Earth. Though Tacke’s evidence was clear, it was basically ignored until Perrier and Segre artificially created the element in a lab and were then given all of the credit that Tacke rightfully deserved. In addition to this injustice, Tacke also published a paper that opened the door to the idea of nuclear fission that would later be taken on by Lise Meitner and Otto Stern. Her paper, five years ahead of its time, described the fundamental processes of fission, though the term hadn’t been invented yet.

She worked from Enrico Fermi’s theory that elements above uranium did exist and offered the explanation that the particles could be broken down when bombarded by neutrons to release a mass amount of energy. Yet again, her paper was basically ignored until 1940 during the Manhattan Project, though Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize for his “discovery” that new radioactive elements were produced during neutron bombardment. Despite her monumental discoveries, Tacke was never recognized (though many blame this on her methods rather than her gender).

5 Esther Lederberg

1922–2006

Esther Lederberg’s gender discrimination consisted more of being overshadowed by her husband, Joshua Lederberg, than being wronged by her male colleagues. Esther’s discoveries were made alongside her husband Joshua. While they both played equally important roles, Esther’s contributions went largely unrecognized as Joshua went on to win a Nobel Prize for their observations.

Esther was the first to solve the problem of reproducing bacterial colonies en masse with the same original geometry using a technique known as replica plating. Her method was incredibly simple in that it only required using a specific type of velvet. Despite a myriad of significant discoveries in biology and genetics, her scientific career was an uphill battle as she fought for recognition from her colleagues. Much of the credit for the discoveries went to her husband Joshua. Her tenure was even revoked by Stanford after being demoted to Adjunct Professor of Medical Microbiology. Joshua, on the other hand, was appointed to be the founder and chairman of the Department of Genetics. Esther was a pivotal partner to Joshua and, despite her diligent work, she remains unrecognized for many of her amazing discoveries.

4 Lise Meitner

1878–1968

The process of nuclear fission was a huge discovery for the scientific world, and few know that a woman by the name of Lise Meitner was the first to hypothesize it. Unfortunately, her work in radiology occurred in the midst of World War II, and she was forced to meet in secret with a chemist by the name of Otto Hahn.

During the Anschluss, Meitner left Stockholm while Hahn and his partner Fritz Strassman continued to work on their experiments with Uranium. The male scientists were puzzled by how the uranium seemed to form atoms that they thought were radium when the uranium was bombarded with neutrons. Meitner wrote to the men posing a theory that the atom may have broken down after bombardment into what was later realized to be barium. This idea had huge implications for the world of chemistry and, working with the help of Otto Frisch, she was able to explain the theory of nuclear fission.

She had also made the observation that no element larger than uranium existed naturally and that nuclear fission had the potential of creating enormous amounts of energy. Meitner was unable to be mentioned in the article published by Strassman and Hahn, though her role in the discovery was severely downplayed by them. The men went on to win a Nobel Prize for their “discovery” in 1944 with no mention of Meitner, which was later claimed to be a “mistake” by the Prize committee. While she didn’t receive the Nobel Prize or formal recognition for her discoveries, Meitner did have element number 119 named after her, which is a pretty good consolation prize.

3 Henrietta Leavitt

1868–1921

While you may have never heard of Henrietta Leavitt, her discoveries revolutionized the fields of both astrology and physics by fundamentally changing the way we see the universe. Without her discoveries, men like Edward Hubble and those that followed her would never have been able to study the universe at its current magnitude. Leavitt’s discoveries have largely gone unmentioned and unrecognized by those who crucially needed them to prove their own theories.

Leavitt began her work by measuring and cataloging stars at the Harvard Observatory. At the time, measuring and cataloging stars under male scientists was one of the few jobs in science that was considered suitable for women. Leavitt was working as a “computer” by doing meticulous and repetitive tasks in order to collect data for her male superiors. She was paid only 30 cents per hour for this mentally grueling work. After cataloging for quite some time, Leavitt began noticing a pattern between the brightness of a star and its distance from the Earth. She later went on to develop an idea known as the period-luminosity relationship, which allowed scientists to figure out how far away a star was from Earth based on its brightness. The universe literally opened up as scientists realized that each star wasn’t just a speck in our own massive galaxy, but a galaxy in and of itself.

Notable astronomers and physicists like Harlow Shapley and Edward Hubble then used her discovery for the basis of their work. Leavitt all but faded away as the Harvard director refused to grant her recognition or credit for her independent discovery. While Mittas Leffler finally noticed her in 1926 for a possible Nobel Prize, she had died before being able to receive the honor. Shapley was then given the prize, boasting that he rightfully deserved the credit for interpreting her findings.

2 Jocelyn Bell Burnell

b. 1943

After being inspired by her father’s books, Burnell began her work with astronomy. She was able to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in physics from the University of Glasgow and went on to Cambridge to earn her PhD. At the time of her discovery, Burnell was working under Antony Hewish studying quasars. While independently working with radio telescopes, Bell noticed specific and constant signals being given off by something in space.

The signals were unlike any known signals they had ever received. Though she didn’t know the source of the signals at the time, the discovery was huge. These signals would later be known as pulsars, which are signals that are given off by neutron stars. These observations were quickly acknowledged and published with Hewish’s name appearing before Burnell’s. Though Burnell had made both the observation and discovery on her own, Hewish later went on to win the 1974 Nobel Prize for his discovery of pulsars. Despite being wronged by not receiving formal credit for her discovery, it’s now universally accepted that she was the first person to make the observation.

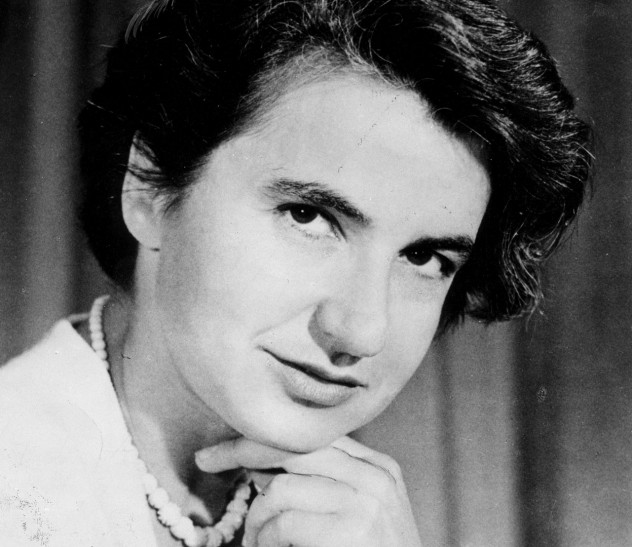

1 Rosalind Franklin

1920–1958

Rosalind Franklin was a brilliant female scientist with probably the most famous case of having her discoveries stolen and being wronged by her male colleagues. If you know anything about science, you’ve probably heard of the names Watson and Crick, credited for the discovery of DNA’s structure. What you may not know is the controversy surrounding their “discovery” and how it was really more of a discovery of the papers Rosalind Franklin had been working on.

At 33, she was hard at work on a yet-to-be-published discovery that would revolutionize biology. She had come to the conclusion that DNA consisted of two chains and a phosphate backbone. The shape was also confirmed by her X-ray experiments of the DNA structure itself as well as her unit cell measurements. Little did she know at the time of her work that her colleagues, Wilkins and Perutz had shown Watson and Crick (who were visiting King’s College) not only her X-ray picture, but even a report with all of her recent findings. With the knowledge in hand, Watson and Crick were all but handed the discovery on a silver platter.

Not only were they given full credit for the observation, Watson then used their friendship to convince Rosalind that she should publish her findings after they published theirs. Unfortunately, this made her work seem more like a confirmation than a discovery. After Watson and Crick being recognized for their “discovery,” they went on to become Nobel Prize–winning scientists with their faces plastered on every biology textbook in American. Rosalind Franklin was left with virtually no recognition.

Shelby is an undergraduate at Arizona State University studying psychology and medicinal biochemistry. She is constantly fascinated by the mysteries of the world around her. She hopes to go on to medical school once she graduates to be able to search for and solve these mysteries.