Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous  Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

Miscellaneous

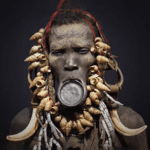

Miscellaneous Ten Groundbreaking Tattoos with Fascinating Backstories

Our World

Our World 10 Green Practices That Actually Make a Difference

Humans

Humans Ten Historic Men Who Deserve Way More Credit Than They Got

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Most Heartwarming Moments in Pixar Films

Travel

Travel Top 10 Religious Architectural Marvels

Creepy

Creepy 10 Haunted Places in Alabama

History

History Top 10 Tragic Facts about England’s 9 Days Queen

Food

Food 10 Weird Foods Inspired by Your Favorite Movies

Religion

Religion 10 Mind-Blowing Claims and Messages Hidden in the Bible Code

Facts

Facts 10 Things You Never Knew about the History of Gambling

10 Tragic Cross-Cultural First Encounters

First encounter stories are generally fascinating and frequently bloody. They can involve explorers or missionaries discovering new lands or foreign military expeditions pushing into new territories in order to gain resources, wealth, and power. However, they are also often muddled with misconceptions.

10 British Missionaries And Ugandan Tribes

Missionaries have often been among the first Europeans to reach previously “uncontacted” peoples. For example, missionary work made inroads into Southern and Central Africa before those regions began to be colonized. Most people have heard of the famous African explorers and missionaries Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone. A less known and less fortunate British missionary of the same era is Bishop James Hannington.

In October 1885, Bishop Hannington was traveling with a supply caravan to meet fellow missionary Alexander Makay. Makay had been allowed to build a mission in Uganda in exchange for carrying out much useful work on behalf of the Ugandan people. Unfortunately, whilst making many converts, Makay also lived under the constant threat of execution from the people’s tyrannical tribal king, Mwanga. A French priest, jealous of the initial successes of the British missionaries, convinced the paranoid Mwanga that Hannington and other intrepid white men like Stanley would “eat up the land” if allowed to meet up and put their heads together. This compelled Mwanga to send a powerful chief, Lubwa, to intercept Hannington before he arrived.

The Bishop was held captive several days, then taken to a clearing outside the village. Nearly all of his 50 disarmed and helpless caravan men were quickly speared to death by Lubwa’s warriors. The dead and dying littered the ground while the Bishop was left standing. As Harrington insisted he had purchased the road to their country with his life, he was finally speared on both sides and killed.

Makay was devastated when news of the Bishop’s death reached him. He worked on in Uganda until 1890 and died of malaria just four days after leaving the country. Within just a few weeks of the news reaching England, over fifty men had offered themselves in the service of the Christian Missionary Society. Uganda inevitably became a British colony as Mwanga had dreaded, achieving full independence in 1962.

9 Saint Augustine And The Welsh

Despite how they’ve sometimes been portrayed, the early Welsh weren’t illiterate primitives. The literary tradition of Wales is actually far older than that of England and the monks of early Wales were dedicated scholars, often fluent in Latin and Greek.

Parts of Britain had already been Christianized during the Roman occupation in 55 BC–450 AD. The area today known as Wales was a hub of Celtic Christianity. When the Romans pulled out of Britain, barbaric tribes of Anglo-Saxon peoples—the first ancestors of the modern-day English—began to invade Celtic Britain from the east and interbreed with or drive the original Britons further westward. The whole land soon became a patchwork of kingdoms, with Saxon kings ruling most of the east. The Celtic Church remained a stronghold of civilization and Christianity in the west, but it was effectively cut off from the rest of Europe.

The situation changed with the arrival of Augustine in 597 AD. He was sent to England by Pope Gregory I to convert the Saxons and he was welcomed by Ethelbert, king of Kent. Soon after arriving, he arranged a meeting with Welsh bishops. He wanted them to abandon the traditions of the Celtic Church and conform to the Roman Catholic way of doing things. Augustine expected them to obey him as the first Archbishop of Canterbury.

The Welsh consulted a wise hermit before meeting Augustine. The hermit said that if Augustine was a true man of God, he would also be gentle and humble of heart. Based on the hermit’s advice, the Welsh decided that if Augustine rose to greet them, they would follow him as a spiritual leader. Instead, Augustine remained seated and appeared proud and severe to them, so they refused to accept him as archbishop or agree to any of his suggestions. Augustine responded furiously, suggesting that God would bring them great hardship and war if they didn’t follow him, and that’s exactly what happened. The king of Northumbria, Aethelfrith, soon left a bloody trail streaking through Wales.

It seems the Welsh were right to regard Augustine as they did. The “man of God” may well have used the power-hungry Aethelfrith as a pawn of Rome. The Welsh, after all, had already been peaceably trying to convert the English pagans for some time. Arguably, they also had no religious obligation to accept Augustine as an archbishop, since their own Saint David had already been made an archbishop by the Patriarch of Jerusalem, but Roman Catholics still dispute this. Most telling of all, perhaps, is that Aethelfrith’s “very great slaughter” included the massacre of thousands of Celtic monks from the monastery at Bangor Iscoed.

8 Romans And Druids

As they say, history repeats itself and is written by the winners. Aethelfrith’s slaughter of the scholarly monks of Bangor Iscoed wasn’t the first time members of an important religious community had been attacked in Wales. Like thousands of other imperialists throughout the ages, the Romans knew that if you wanted to conquer a people, the best place to strike was at their intellectual and cultural heart. The druids were the keepers of knowledge and tradition for the ancient Britons and the Isle of Anglesey was the sacred heart of the druidic religion.

There are few facts left about the original druids. We know they were a priestly class among the Celtic peoples of Britain and Ireland before Christianity and greatly admired by Julius Cesar, but the Roman army destroyed them without a trace. The decline of druidism began in earnest when Gaius Suetonius Paulinus invaded Anglesey during the Roman Conquest of Britain in around 60 CE. A massacre resulted, as recorded by the historian Tacitus in the 14th book of his Annals:

“On the shore stood the opposing army with its dense array of warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair disheveled, waving brands. All around, the Druids, lifting up their hands to heaven, and pouring forth dreadful imprecations, scared our soldiers by the unfamiliar sight, so that, as if their limbs were paralysed, stood motionless, exposed to wounds. Then urged by their general’s appeals, and mutual encouragements not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards, smote down all resistance, and wrapped the foe in the flames of his own brands. A force was next set over the conquered, and their groves, devoted to inhuman superstitions, were destroyed.”

7 Romans And Gauls

Long before they could reach Britain, the Romans first had to subdue the Celtic peoples known as the Gauls. The Gauls had occupied much of what is today known as France. Rome’s first encounter with the Gauls resulted in a humiliating defeat—and it happened right in the Romans’ own backyard.

A tribe of Gauls called the Senones crossed the Alps and settled in northern Italy in around the fourth century B.C. According to Plutarch’s account, they’d come because they’d fallen in love with wine. They soon began seizing territory and found themselves in conflict with Etruscan tribes already in the region, who petitioned Rome for help.

Rome sent their best ambassadors, seeking to make peace. When the ambassadors asked the Gauls what grievance they had against the Etruscans, the Gallic leader, Brennus, explained that his people simply wanted land. Brennus turned the Romans’ own history of conquest around on them. Hadn’t the Romans already done exactly the same thing with several other peoples already? How could they then claim that the Gauls were wrong to take from the Etruscans? It’s not clear why—perhaps Brennus had offended them—but after hearing this, the ambassadors themselves entered the conflict against the Gauls.

The violation of conventional diplomacy enraged Brennus. He promptly drove his army southward, where Rome was unprepared and undefended. The Gauls defeated Quintus Sulpicius’s army of 40,000 at the Battle of Allia, then laid siege to Rome itself. The Romans agreed to pay a ransom on the condition that the Gauls would turn back and leave them alone. The agreed amount was paid, heaped on a set of weighing scales, but Brennus decided in a display of bravado that it should be tipped in favor of the winners and the Romans ended up having to pay nearly double. They never forgot their humiliation at the hands of Brennus and showed little mercy later on when they began expanding their empire deep into Gallic territory.

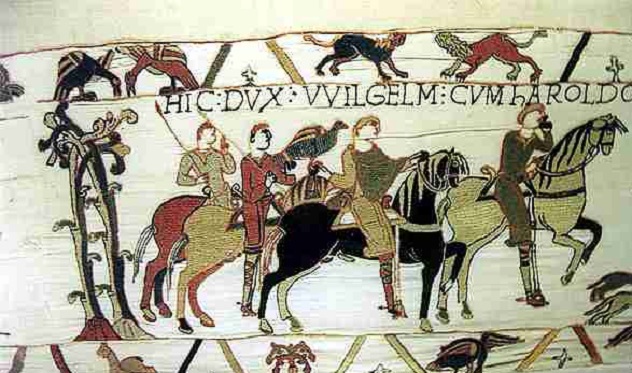

6 De Hautevilles And Sicilians

The Normans are mainly remembered for their conquest of England in 1066, famously commemorated in the Bayeux Tapestry. A less commonly known fact is that the Normans also advanced south, as far as the regions of Southern Italy. By that stage of history, the Roman Empire had dissolved. The Roman papacy had begun to wield power instead.

In 1059, the time leading up to the first Crusade, some mercenary Norman knights pledged allegiance to the pope of Rome, Nicholas II. Their leader, Robert de Hauteville—commonly known as “Guiscard”—was given banners, lands, and the presumptuous title “future Duke of Sicily.” It was a less than subtle hint that De Hauteville and his men, who had never even set foot in Sicily before, should quit plundering and terrorizing the Southern Italians, cross the Messina strait, and conquer the Muslim-controlled island instead.

An advanced party of some 250 horsemen came in the night in May 1061, led by de Hauteville’s brother Roger. They took a longer route and landed to the south of Messina, which the Saracens weren’t expecting. At dawn, Roger and his men encountered a supply caravan on its way to the city. In minutes, they’d slaughtered everyone. Looking out to sea, they saw the sails of ships bringing reinforcements and pressed on to Messina itself. They were now almost 500-strong and they knew that Robert de Hauteville would soon be landing with thousands more. The city was quiet and apparently undefended. Luck was with them. Why wait?

The inhabitants of Messina had become too paranoid at the prospect of being invaded from the mainland. They expected the Normans to cross at the narrowest point to the north and had concentrated all their military forces there, leaving the city undefended. Messina fell in minutes and the Saracen army found themselves locked out. They’d fled inland by the time de Hauteville arrived. In the meantime, those citizens who couldn’t escape were put to the sword. The long campaign for Sicily didn’t remain so easy for the Normans—at one point, de Hauteville barely escaped with his life.

5 Christian Missionaries And Huaorani

The Huaorani people still live in the Amazonian rainforests of Ecuador today. Prior to contact with the modern world, they had been locked into a deadly cycle of unending violence for centuries. Murderous raids on rival groups and retaliatory killings were a big part of their culture. When American missionaries arrived in 1956 and made camp on a sandbar known as Palm Beach on the Curaray River—an area located in Huaorani territory—the result was disastrous.

Five evangelical Christians were attacked by a group of Huaorani warriors on the January 8, and the Huaorani couldn’t understand why the men didn’t defend themselves despite having guns. The missionaries fired warning shots into the air, but wouldn’t shoot directly at the Huaorani. One tribesman, watching from thick cover, was hit by a stray bullet, but this was apparently unintentional. The missionaries would not be so fortunate. All five were speared to death.

Rachel Saint, sister of slain missionary Nate Saint, continued the evangelizing work her brother had initially set out to do. Her courage, conviction, and commitment to non-violence impressed the Huaorani and helped many to abandon a brutal pattern of life and begin living peacefully. At one point, when she heard of two brothers who were making spears and about to set off on a vengeance mission, she burst into their huts, yelled at them, and broke the spears in pieces. The brothers were respected, proven warriors who could have easily killed her for doing this. Instead, they abandoned their planned attack.

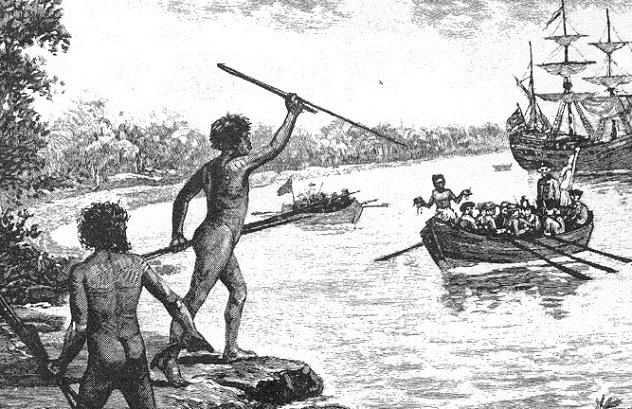

4 Europeans And Australian Aborigines

Cook’s arrival in Australia may shed light on a popular misconception. One first encounter story claims that South American natives couldn’t see Magellan’s ships anchored offshore because they were suffering from some kind of conceptual blindness. The ships were completely alien to their experience, so far beyond their comprehension that they literally didn’t see them. Only the local shaman could see the ships, according to legend, and he had to “initiate” the rest of the tribe out of their selective blindness in order for them to see Magellan’s fleet.

Wherever this story originates, it doesn’t originate with Magellan and his men. No surviving account of the famous voyage ever mentions such an incident. The most detailed account is the journal of Antonio Pigafetta. According to Pigafetta, the locals at Rio de Janeiro and Rio de la Plata on each occasion had no apparent trouble sighting Magellan’s fleet. Instead, the native Brazilians thought the ships were literal mother ships—living entities that gave birth to the smaller boats in which Magellan and his men came ashore. When the boats returned to the ships and rested alongside, the locals thought the ships were breastfeeding the smaller craft.

The story about natives being unable to see the ships of explorers may have originated in Australia. Europeans were used to first encounters being big, exciting events. The Europeans and their ships were always the center of great attention and curiosity, but when Cook’s ship arrived off the Australian coast in April 1770, it provoked no apparent reaction. Sir John Banks, a naturalist aboard Cook’s ship, noted in his journal that the native people barely glanced their way, wondering if perhaps they couldn’t hear their approach for the noise of the waves. Captain Cook himself was likewise disappointed at the lack of response. This may perhaps be the origin of the story of natives being unable to see European ships.

Another common misconception is that Aborigines were hostile towards Europeans from the beginning. In reality, many tribes made efforts to make room for European settlers within their societies. It was the colonists who showed a poor attitude. They had no respect for Aboriginal laws and took food, resources, and even people without permission, which understandably provoked the Aborigines to war. This was convenient for the colonists, who deliberately annihilated many Aboriginal groups.

3 Various Imperialists And Solomon Islanders

The Solomon Islands were first discovered by Europeans in 1568. The Spaniard Álvaro de Mendaña de Neira claimed to have found gold deposits there. Believing he’d discovered the source of the biblical King Solomon’s gold, he named the region “Islas de Solomón.” French and English navigators followed after the Spanish. First encounters were often bloody affairs since the native tribes consisted of violent headhunters who were used to raiding and killing one another. Colonials were still having troubles in the late 1800s amidst swirling reports of coastal raids and “cannibal feasts.” The British Navy ended up having to bomb headhunting settlements from offshore.

Imperialist Japan invaded the Solomon Islands in 1942 during World War II. The Solomon Islands were seen by the Japanese as a convenient stop on the way to a planned invasion of Australia. However, subduing the local population once again proved much harder than assumed, even though Solomon Islanders had by that stage mostly conformed to the habits and expectations of Christian missionaries and British colonials.

The Solomon Islanders sided with the Allies and some enlisted as soldiers. Former policeman Jacob Vouza was captured but survived being tortured by the Japanese without ever divulging information about Allied positions. Others fought the Japanese independently. Men from the south coast of Guadalcanal initiated their own guerrilla attack on a Japanese post and managed to wipe out the entire unit.

If first encounters with the Japanese were harrowing for the Solomon Islanders, their first meetings with American soldiers were more positive. Inspired by American ideals of liberty and independence, Solomon Islanders formed protest movements after the war and finally broke free of British rule in the 1970s.

2 Taino And Spaniards

The Taino people were native to the Caribbean prior to the arrival of Columbus in 1492. They were already on the defensive against waves of more aggressive Caribbean tribes when the Europeans first arrived. A cruel genocidal bloodbath followed, described by a Dominican friar who witnessed the atrocities first hand:

“The Spaniards . . . well weapon’d with Lances and Swords, begin to exercise their bloody Butcheries and Strategems, and overrunning their Cities and Towns, spar’d no Age, or Sex, nay not so much as Women with Child, but ripping up their Bellies, tore them alive in pieces. They laid Wagers among themselves, who should with a Sword at one blow cut, or divide a Man in two; or which of them should decollate or behead a Man, with the greatest dexterity; nay farther, which should sheath his Sword in the Bowels of a Man with the quickest dispatch and expedition. They snatcht young Babes from the Mothers Breasts, and then dasht out the brains of those innocents against the Rocks; others they cast into Rivers scoffing and jeering them, and call’d upon their Bodies when falling with derision, the true testimony of their Cruelty, to come to them, and inhumanely exposing others to their Merciless Swords, together with the Mothers that gave them Life.”

The friar presented his account of these atrocities to the Spanish king in 1542. The king was moved to set laws encouraging better treatment of native peoples in foreign lands. Sadly, these laws were rarely applied by the conquistadors in the “New World.”

1 The Macho-Piro And Eco-Tourists

First encounters are still happening. With all our modern technology, it’s easy to think that the whole world has already been discovered, but there are still hundreds of tribes around the world who remain isolated from modern life. Our modern way of thinking and seeing the world is completely alien to them. The Amondawa tribe, for example, were first discovered by anthropologists in 1986, and they were found to have no abstract concept of time.

The Mashco-Piro are one of several tribes in the Amazon Basin designated by the Peruvian government as “uncontacted people.” Contact is forbidden, since the immune systems of these mysterious people would be unlikely to cope with the kinds of germs commonly hosted and easily fought off by most Peruvians. First encounters with these people have occurred, however, and they have been seen to emerge from the forests to ask for modern items such as machetes and cooking pots.

Encounters with the Macho-Piro have sometimes taken violent turns as the territory of these natives is more and more encroached upon by increased logging and urbanization. A native from a different tribe who spoke a related language and had maintained a relationship with the Macho-Piro for some time was pierced through the heart and killed by them in 2011, while arrows have been fired at park rangers and tourists passing in boats.

HTR Williams lives and writes in New Zealand. Read more articles and fiction for free at htrwilliams.com