History

History  History

History  Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Cases of Grabbing Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

History

History 10 Common Misconceptions About the Renaissance

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Crazy Things Resulting from Hidden Contract Provisions

Facts

Facts 10 Unusual Facts About Calories

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Days of Humiliation When the Person Should Have Stayed in Bed

Humans

Humans 10 Surprising Ways Game Theory Rules Your Daily Life

Food

Food 10 Popular (and Weird) Ancient Foods

Animals

Animals Ten Bizarre Creatures from Beneath the Waves

Technology

Technology 10 Unexpected Things Scientists Made Using DNA

History

History 10 Events That Unexpectedly Changed American Life

Pop Culture

Pop Culture 10 Cases of Grabbing Defeat from the Jaws of Victory

History

History 10 Common Misconceptions About the Renaissance

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Crazy Things Resulting from Hidden Contract Provisions

Facts

Facts 10 Unusual Facts About Calories

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Days of Humiliation When the Person Should Have Stayed in Bed

Humans

Humans 10 Surprising Ways Game Theory Rules Your Daily Life

Food

Food 10 Popular (and Weird) Ancient Foods

Animals

Animals Ten Bizarre Creatures from Beneath the Waves

Technology

Technology 10 Unexpected Things Scientists Made Using DNA

10 Reasons 19th Century Paris Was As Miserable As Les Mis

By now you’ve probably either seen the movie, watched the play or read the book Les Miserables, Victor Hugo’s classic tale of life in nineteenth century Paris. But have you ever wondered if life in Paris at that time really was as miserable as the movie depicts? Here are ten reasons why it was even worse:

Opportunities for lower class women to move ahead were few and far between, to say the least. The world was most certainly not their oyster: among their few career options were the roles of domestic servant, seamstress, laundress—and when all else failed, prostitute. And each occupation brought with it a distinct set of challenges.

Prostitutes were of course viewed as the lowest of all, and they often suffered from police persecution. But even more shocking than that was the fact that many women were actually falsely accused of prostitution. Many such women were domestic servants, accused by the wives of the families they worked for after being seduced by the husbands.

Women were also regularly charged with slander and public drunkenness. Neither crime is gender-specific—but only in women was the behavior deemed criminal.

Children were abandoned on a fairly regular basis. The lucky ones were dropped off at state-run hospices, where they usually remained until they turned twenty-five. At the hospices the children were given the basic necessities: food, clothing and shelter. No education was provided—and due to severe overcrowding, very little attention was paid to each child.

The even unluckier children were forced to live on the streets and fend for themselves. In these cases, children turned to begging and thievery in order to survive.

If they were (arguably) a little luckier, they would be taken in by strangers—much like Cosette in Les Mis— in which case they would often be forced to perform heavy labor. They were usually given minimal food and shelter, and would be mistreated or neglected on a regular basis. But the unluckiest children of all were forced to turn to:

Child prostitution was rampant in nineteenth century Paris. The young girls—usually pre-pubescent—were forced into sexual encounters by men of the upper classes, and were usually paid as little as a single franc. Usually the act was consummated in a back alley or under a bridge. Sometimes a room in the girl’s own house might suffice.

Some legitimate businesses served as fronts for prostitution; they would send children to wealthy homes as “deliveries.” If a girl was old enough to be impregnated by the client, her family would in many cases throw her onto the streets for bringing shame upon the family. Left destitute and alone, the girl would then become a full-time streetwalker.

They might have been the most hard-working, God-fearing people in Paris—but according to the upper classes, the poor and huddled masses were dangerous and despicable.

Crime was admittedly everywhere in nineteenth century Paris, and real criminals were certainly dangerous. This caused grave problems for the many poor people who were not criminals, since the upper class viewed them all—innocent workmen like Jean Valjean included—as the “dangerous class,” to be held in contempt and ridicule.

Even though women were pretty much stuck where they were, it seems that men had it no better.

Parisian men—especially unskilled laborers—suffered high rates of mortality due to accidents on shipping docks, in workshops and on construction sites. Along with these dangerous work conditions, men had to contend with dangerous rivalries between workers from different regions in France. If for example a worker from Saint Georges happened to find himself working on the same construction site as a worker from Montparnasse, the result could be a deadly.

Many men were also forced into military service. Those few who survived for long would be prevented from marrying while they served by poor pay and strict army regulations.

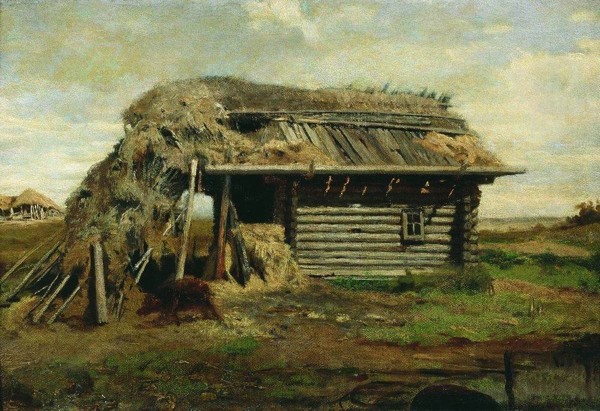

The poor of nineteenth century Paris were concentrated in the ancient center of the city, where the buildings were in a state of disrepair and families of six to ten people lived in one-room apartments. These apartments had no running water and no indoor plumbing—and the nearest restroom was often on the streets outside.

In the outskirts of Paris, families would often share huts with their livestock. The family and livestock used the same entrance to the hut, but were divided by a partition that separated the animals from a room that served as both the kitchen and bedroom. A loft that hung above the kitchen was used to dry out the animal feed. The feed would be spread across a plank floor, meaning that bits of seed and straw would frequently drop down onto the kitchen table where the family ate their meals.

Since there was no indoor plumbing in many of the homes, the smell of raw sewage was absolutely everywhere: whether you were rich or poor, you’d struggle to escape the foul stench.

The sewage smell was made spicier by inescapable body odors, for it was often too cold or too inconvenient to bathe. On the rare occasions when people did bathe, they used low tubs filled with only a few inches of water—which wasn’t exactly the best remedy for the thick layers of slime clogging their pores.

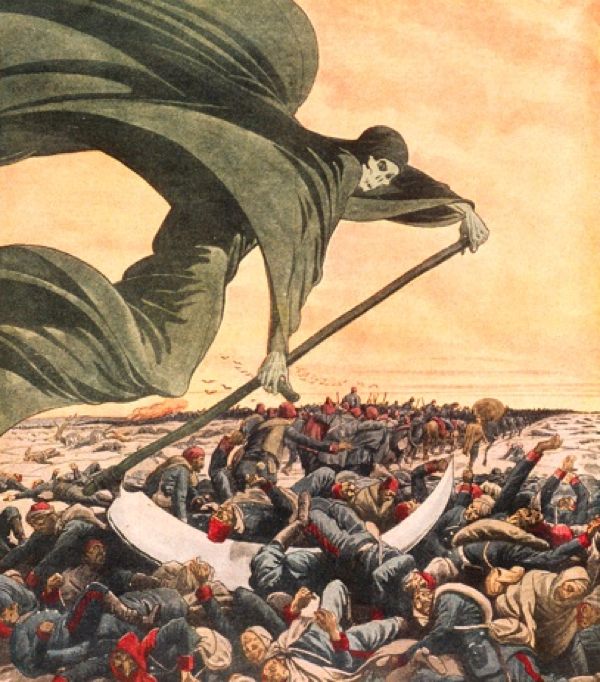

With all the raw sewage that Paris had to contend with, it was only a matter of time before cholera hit the city hard.

Doctors found it difficult to diagnose the disease. The symptoms included everything from high fevers to chest pains and vomiting to headaches, and the disease could leave its victims bedridden in a matter of hours. The cholera epidemic of 1832 lasted six months, and resulted in 19,000 deaths.

Death was everywhere—and for many Parisians, death was something to be embraced rather than feared. In fact, what would be considered morbid today merely piqued the curiosity of many Parisians, who relished the most frightening tales of slaughter as much as they enjoyed the gruesome spectacle. In no instance is this more apparent than the popularity of the Paris Morgue.

Built in 1864, the Paris Morgue was the place where the bodies of the unidentified dead—many of them suicide cases—were displayed on marble slabs for friends or family to identify. The morgue soon became a fixture for Parisians, with tens or even hundreds of people shuffling into the room to gawk at the dead and gossip over their cause of death.

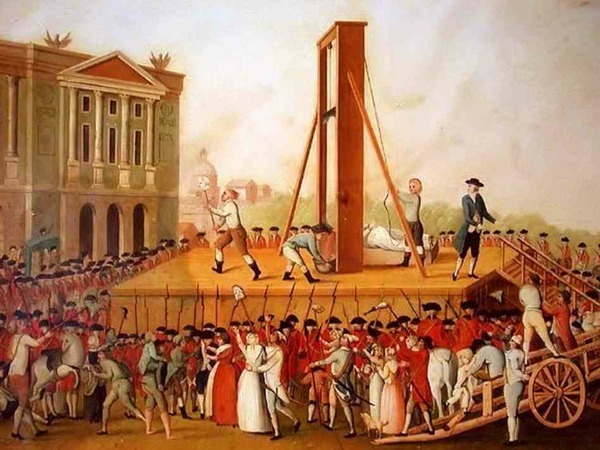

This entry may not strictly apply to the nineteenth century, but its repercussions were certainly felt throughout that period (and in Les Mis), and it seemed too gruesome to leave off the list. The Reign of Terror took place between June 1793 and July 1794, as French revolutionaries struggled to secure their power after the overthrow of the monarchy. Paris was thrown into chaos, and the new government into a state of utter paranoia.

After King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette were executed in 1793, Maximilien Robespierre rose to become one of the most powerful and feared men in the country. Under his dreadful rule, thousands of citizens’ heads were chopped off at the guillotine—many of them without trials, or even explanations.

Commoners, intellectuals, politicians and prostitutes—nobody was safe from the Terror. A mere suspicion of “crimes against liberty” was enough to earn one an appointment with Madame Guillotine, also called The National Razor . The final death toll for this most miserable of periods is thought to have been between 16,000 and 40,000.