Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Flops That Found Their Way to Cult Classic Status

History

History 10 Things You Never Knew About Presidential First Ladies

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Zombie Movies That Will Actually Terrify You

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Humans

Humans 10 Times Scientists Were Absolutely Sure… and Absolutely Wrong

Our World

Our World 10 Pivotal Moments for Life on Earth

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Most Realistic Medical TV Shows of All Time

Creepy

Creepy 10 Eerie & Mysterious Ghosts of the Pacific Coast

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Typos That Accidentally Changed History

History

History 10 Times Trickery Won Battles

Technology

Technology 10 Awesome Upgrades to Common Household Items

10 More Incredible Archaeological Discoveries

Mankind has always been fascinated by the past. From obscure farmers who uncover old remnants from wars among the Ancient Greeks, to the professionals who continue to unearth Pompeii—we all love to think of the lives of those who passed through the world long before we were given the chance.

Following on from an older list, here are ten more of the most important archaeological discoveries. For the purpose of this list I am defining importance as “revealing the most about the past,” rather than as merely being impressive. The Terra-cotta Army, for example, is awe-inspiring—but it is not as informative as the following discoveries. At least that’s what I am arguing . . . .

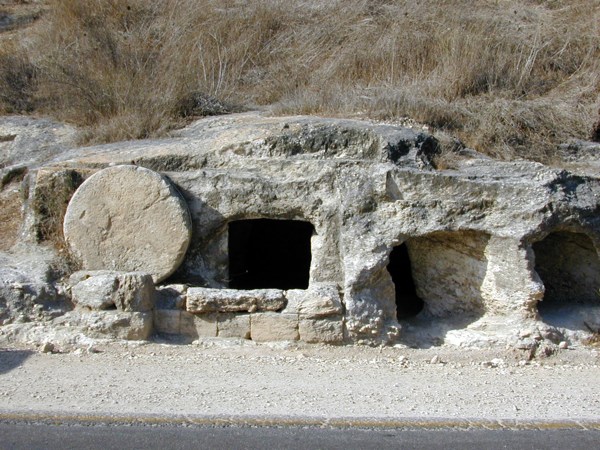

Animals as diverse as dogs, geese, and elephants have been seen to mourn their dead. Yet once their mourning is over, they leave their dead to rot and move on with their lives. It is only humans who bury their dead and seem to worship the spot of interment. But at what point in history did simply leaving the corpse of a fellow human evolve into ritualized burial?

The earliest sure evidence of burial-with-a-purpose in humans can be traced to around 100,000 years ago. In the caves of Mount Carmel in Israel, the graves of several modern humans have been found. The bodies appear to have been buried with seashells, which must have come quite some distance from the ocean. The shells would have been unfit for use as food in the hot and unhygienic desert—it’s more likely that they were used as jewelry, and as ritual offerings for the dead.

Burials are so fascinating because they often take a lot of work on the part of the living—and since it’s work that carries no benefit to survival, burials may offer insights into how and why societies have evolved.

It is possible that it was not modern Homo sapiens who were the first to bury their dead with honors. Neanderthals may have placed their dead in the Pontnewydd Cave in Wales as long as 250,000 years ago.

Bronze-making is considered the second historical leap in metal-working. Very few metals are workable in their native form—and these include, for example, gold and silver. Bronze is an alloy of copper and tin, and it’s stronger than either metal.

Unfortunately for the humans of the Bronze Age, tin deposits were rather rare in Europe. Fortunately for civilization, this created a consuming need for trade among different peoples. There are plenty of sources that refer to the import of tin from distant places. One of the few tin deposits in Europe can be found in Cornwall, England—and Herodotus talks of the “Cassiterides,” or Tin Islands, from where the Greeks imported their tin.

Archaeological research around the tin mines of Cornwall show that they have been in use for thousands of years. Finds of goods imported from the Mediterranean show that trade existed between these far flung communities during the Bronze Age. Even in the distant past, the world was not so isolated as we might have imagined.

Until the nineteenth century, almost every educated person would have said that Troy—the city at the centre of The Iliad and The Odyssey—was purely legendary.

People in the ancient world believed that the city of Troy, as well as the Trojan War, were entirely historical. But it was only in 1871 that the physical remains of Troy were discovered, at Hissarlik in Turkey. The discovery was made by Heinrich Schliemann, who followed textual evidence in the epics by Homer and other ancient references to find the city.

Modern archaeologists find the methods of excavation used by Schliemann to be destructive—but they were the best available at the time. Despite his lack of care in digging through various layers of history, Schliemann discovered a vast cache of treasure inside the mighty walls of the city. But it is not for the gold he found that I include Troy in this list: I include it for what it reveals. The rediscovery of Troy shows that it is entirely possible for oral and folk tales to maintain fairly accurate records of the past.

The earliest polished tools—most notably axes—were discovered in Japan, and are thought to be around 30,000 years old. The axes are thought to have played an important role in the massive clearing of forests which took place during the Neolithic period, as humans began to prepare land for farming. But the tools seem to have had a purpose even more incredible than the practical function for which they were originally built.

The enormous practical importance of the axes seems to have turned them into a symbol of social prestige. Some have been found that are too large and heavy for a man to carry—suggesting that they were some of the first known objects created entirely for the bragging rights of the owner. If this were true, it would signal a huge leap in the social evolution of humankind.

And there’s more: after a time, the axes began to symbolize not only the merit of a man while he was alive, but also his legacy after death. Men seem to have been honored in death by being buried with their axes, and it is thought that the axe eventually became a symbol of the society’s collective memory of an individual, much like tombstones today.

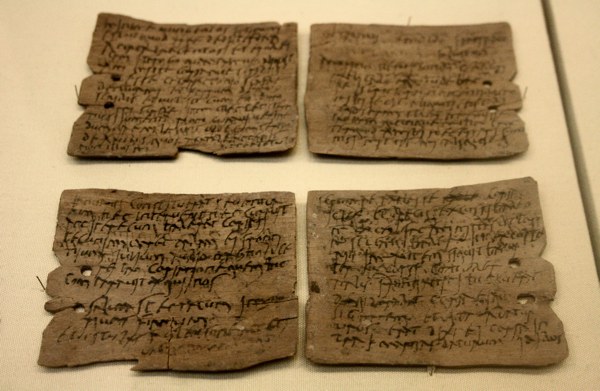

Debate still rages as to the function of Hadrian’s Wall, in northern England: was it defensive, or merely a trade barrier? The fort at Vindolanda gives us an insight into the people who lived there—as well as the people who lived in the Roman Empire at the height of its power.

Those who lived on the wall used thin sheets of wood to write on, papyrus being far too expensive to import from the southern provinces. The tablets contained not the grand inscriptions of the Emperors but the simple notes between soldiers, and even their wives.

One soldier, for example, in a tablet addressed but probably not sent to Emperor Hadrian, writes: “As befits an honest man I implore Your Majesty not to allow me, an innocent man, to have been beaten with rods . . . .” These writings allow us a unique view into the life of common soldiers at the time of the Roman empire.

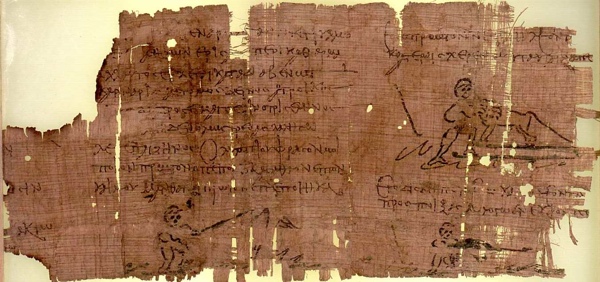

Oxyrhynchus was a city in the south of Egypt. There was nothing particularly noteworthy about the ancient city—and were it not for a quirk of the environment, it would be unlikely that anyone but a specialist in Egyptology would have heard of it today.

But many things have been preserved in the dry desert sands of Oxyrhynchus. When people were done with texts in the ancient city, they simply dumped them into rubbish pits in the same way that we would bin newspapers today. The people who disposed of writings in this way would have had no idea that archaeologists would one day treasure every fragment that they could pull from a dump.

So much ancient literature has been found that its importance cannot be overstated. Vast numbers of texts are still being found. So many, in fact, that the archaeologists are using crowd-sourcing to transcribe all the fragments. Anyone wishing to play at archaeology should go to this amazing website. If you uncover something funny by Menander, be sure to drop me a line.

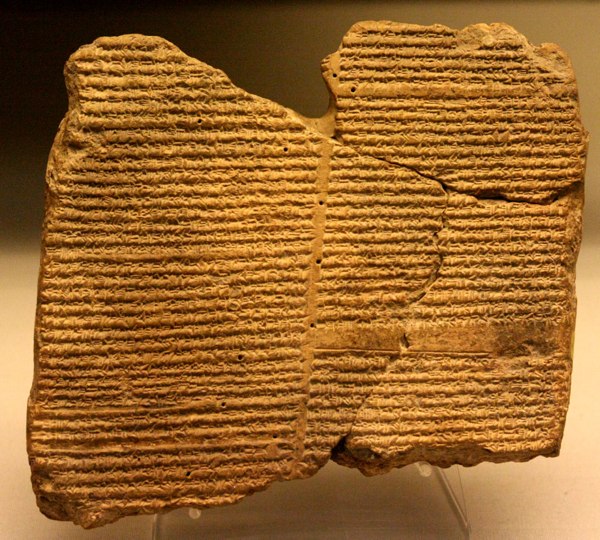

The library of Ashurbanipal, also known as the library of Nineveh, is the oldest collection of translatable writing on the planet. The civilization which flourished between the rivers Tigris and Euphrates is considered the first true civilization. To manage such a civilization, it was necessary for the kings of Mesopotamia to find a method of transmitting their orders and recording their belongings.

It is thought that writing originated as a system of invoicing. Within the Library of Ashurbanipal (the King of Assyria) can be found the evolution of writing. For those who seek personal connection with the past, there can be no more touching record than the epic of Gilgamesh—the story of a man who, after the death of his friend, searches for the reason all men must die.

“In fourteen hundred and ninety two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

The small rhyme above is taught to many students—and it is right, as far as things go. The problem with the memory aid is that it teaches people to remember Columbus as the first European to reach the New World. This idea is wrong on at least one count. Europeans had visited the American continent nearly five hundred years before Columbus was born.

L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland is the site of a Viking settlement in the New World. Erik’s Saga is an Icelandic poem which tells of the founding of a settlement in Vinland, North America. Like the tales of Troy, it was considered to be nothing more than legend until the ruined site was discovered—an event that signaled a huge shift in the history of exploration. L’Anse aux Meadows teaches us that discoveries—as important as that of an entirely new continent—can be forgotten.

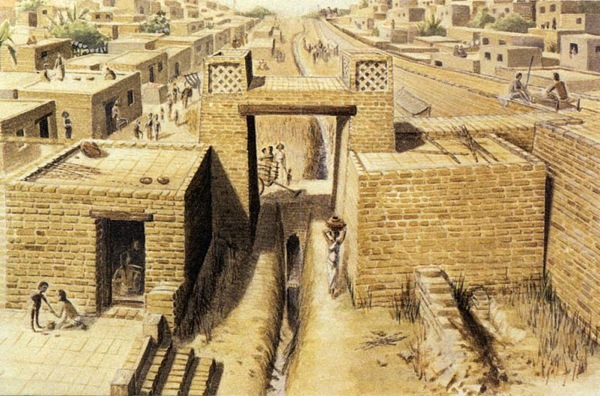

If a continent can be forgotten, then why not an entire civilization? The three most ancient civilizations all sprung up alongside rivers. The Nile and Mesopotamian civilizations were never forgotten—but a whole flourishing of human endeavor along the Indus river was lost until the twentieth century.

All along the Indus river, advanced cities were built. Signs of science, writing, and technology can be found in the ruins of the unearthed cities. Why the Indus Valley civilization failed is not known—but we can see from the archaeological digs that the cities were often destroyed by the rivers that had given them life. The art of the Indus Valley Civilization is often thought to show a remarkable level of social equality. If this interpretation is true—if societies do not move smoothly from tyrannies to democracies over time—it has profound implications for historians.

Gobekli Tepe has revolutionized the way archaeologists have seen the past. The site, on a hill in Turkey, is the oldest monumental human construction in the world. The site contains large, upright stones, and complex carvings of animals.

Some think it was built as many as 12,000 years ago. This would predate the time when simple villages were formed in the Near East—and yet some level of social organization would be needed to raise stones such as the ones seen at Gobekli Tepe. The carvings seen there may even be representative—making them the earliest known form of writing. Much work remains to be done at the site, but it is clear that humans came together to form complex societies far earlier than we initially thought.