Technology

Technology  Technology

Technology  Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Icelandic Culture Makes Other Countries Look Boring

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Common Misconceptions About the Victorian Era

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Strange Unexplained Mysteries of 2025

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of History’s Most Bell-Ringing Finishing Moves

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Icelandic Culture Makes Other Countries Look Boring

Misconceptions

Misconceptions 10 Common Misconceptions About the Victorian Era

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Strange Unexplained Mysteries of 2025

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 of History’s Most Bell-Ringing Finishing Moves

10 Old-Timers Who Kicked Ass During Wartime

George McGovern once said that he was “fed up to the ears with old men dreaming up wars for young men to die in.” War is indeed the battleground where youthful exuberance and martial prowess combine to create a killing machine, but there are soldiers from history who, despite being marginally older, were also wiser and more patient. In times of great need and peril, they truly showed courage and self-worth. Perhaps it’s about time we learned a thing or two from them.

10The Calcutta Light Horse

The Calcutta Light Horse was originally formed to be part of the Cavalry Reserves of the British Army in India. When World War II broke out, the vaunted group—which had its heyday during the Boer Wars—was no longer a tough fighting force. By then, it was a gentleman’s regiment comprised of middle-aged accountants, tea planters, and merchants, “used to more rounds in the club bar than rounds on the firing range.” But alongside another auxiliary regiment called the Calcutta Scottish, the Calcutta Light Horse was to show the world what even veterans far removed from battle can do when called upon for duty to king and country.

The target was the German ship Ehrenfels, as well as three other Axis merchantmen. The British believed these ships were scouting British vessels in the region and then transmitting vital information to U-boats. Since the ships were anchored off Goa, India—which was a territory of Portugal at the time—no direct military action could be taken. Any attempt to do so would have violated Portuguese neutrality and could have driven the country into the Axis camp.

The Special Operations Executive (SOE) tasked the ragtag group of old-timers with infiltrating the Ehrenfels, taking out the enemies, and retrieving intelligence documents. By 2:30 AM on March 10, 1943, Operation Creek was underway. The SOE disguised the raid as “a wild party on the streets of Goa gone awry.” Under cover of the noise, 14 middle-aged veterans from the Calcutta Light Horse and four from the Calcutta Scottish mounted a daring assault on the German ship.

The captain of the Ehrenfels was one of the first to be killed in the assault. Alhough the radio codes were destroyed, the men captured the transmitter. The Ehrenfels slowly filled with seawater due to sabotage while the three other Axis vessels exploded in a bright haze. After 20 minutes, the signal was given for the men to escape, which they did with only relatively minor injuries. This daring raid where balding, overweight, and aging veterans took down German naval intelligence was immortalized in the 1980 film The Sea Wolves.

9The Greybeards

The 37th Regiment of the Iowa Volunteer Infantry was a unique group of soldiers known as the Greybeards. These men were past the age of exemption from military service, but they remained fit and healthy enough to fulfill their duty, so they did.

The regiment was the brainchild of a 50-year-old Iowa farmer named George Kincaid. By the second year of the US Civil War, the number of volunteers in Iowa had dwindled, so Kincaid came up with the plan to recruit able men above a certain age who would show “a wonderful expression of loyalty and patriotism” despite being farmers and tradesmen by craft. The image of old men, their hair and beards white with age, boisterously marching to war shamed the youth and subsequently bolstered recruitment in the state.

Many of the men from the regiment’s original roster were above 60 or 70 years old, and one had even reached 80. The primary task of the Greybeards was garrison duty, which was not as easy as it sounds, requiring the handful of old-timers to guard thousands of unruly rebel soldiers. They were exposed to enemy fire on numerous occasions during Confederate raids, though most of their casualties were victims of disease. One of the most notable Greybeards was Anton Busch, a German immigrant who was already 52 when he fought for the Union as part of the 37th Iowa.

8The Monuments Men

The men and women of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives unit (MFAA, better known as the “Monuments Men”) weren’t that old by general standards, but compared to the average citizen who volunteered for active service during World War II, they were ancient. They were so far removed from battle that it was insane to send them on covert missions to active war zones, but sent they were, all in the name of arts and culture.

The concept, “a corps of specialists to deal with the matter of protecting monuments and works of art,” was initially conceived by Francis Henry Taylor, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The unit was comprised of museum directors, curators, art historians, and educators, some of whom were veterans of the Great War.

As World War II dragged on, the costs were even higher than the men and material sacrificed for the war effort—it also included priceless artifacts and works of our shared human history. The Monuments Men had to contend with the decadence of Hermann Goering, the destruction left in the wake of the advancing Soviets, and even raucous and careless Allied soldiers, who were reported for vandalizing historic sites in Naples.

Perhaps the greatest threat was Hitler’s Nero Decree, which stated that “anything else of value within Reich territory, which could in any way be used by the enemy, will be destroyed.” One Nazi disciple, August Eigruber, interpreted Hitler’s order as a signal to destroy the Altaussee mine in Austria. The mine housed countless treasures, such as Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges and Vermeer’s The Astronomer. The Monuments Men raced against time to prevent the destruction of these works and countless others, braving the war-torn landscapes of Italy, France, Germany, and Austria to preserve our cultural heritage.

7Henry Webber And Caspar Rene Gregory

Henry Webber was 67 years old when World War I broke out. His three sons eagerly volunteered for the British armed forces, and councilman Webber desired to serve alongside his sons and prove his own worth in battle. His first attempt to volunteer was rejected, as he was 20 years over the age limit. For his next attempt, he recruited younger cavalrymen and offered the entire unit to the army, but he was again rebuffed. Finally, on July 26, 1915, he was given a commission partly due to his unyielding resolve to enlist, serving with the 7th South Lancashire battalion.

His fellow soldiers were unsure of his age, though his commanding officer found out that his own father and Webber had rowed together. Webber and the 7th South Lancashire saw significant action in the capture of the town of La Boiselle on July 3, 1916 as part of the Somme Offensive. Tragedy struck barely three weeks later when Webber and his men were struck by artillery fire and Webber suffered a head wound, to which he succumbed the next day. Webber never realized his dreams of fighting alongside his sons, all of whom survived the war.

On the opposite side of the trenches, Caspar Rene Gregory was also a beloved and respected member of his community. The German-American was a brilliant theologian, scholar, and educator, renowned in Leipzig for his study of the translations of the New Testament. His works, such as the Textkritik des Neuen Testaments and Die Griechischen Handschriften des Neuen Testaments, were considered seminal theological discourses.

When war was declared, Gregory was nearing the tender age of 68, but he felt it was his duty as a German to offer his life for the Vaterland. He was highly revered by his comrades and showed his mettle in battles such as Lille and Ypres. Sadly, upon reaching the age of 70, Gregory met an unfortunate fate when his horse threw him off the saddle. While recuperating from the injury, the village where he was staying was bombarded by artillery, and Gregory died on April 8, 1917 as a result.

6Huang Zhong And Yan Yan

While there is no actual historical evidence that either Huang Zhong or Yan Yan were extremely old, they have been depicted as such for centuries thanks to Luo Guangzhong’s classic novel, Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Both generals were renowned warriors under Liu Bei and the Kingdom of Shu-Han, forces that were loyal to the Han government.

Huang Zhong was an old general known for greatly exaggerated feats like the ability to bend a 136-kilogram (300 lb) bow. One chapter in the novel details the revered God of War Guan Yu’s mission to besiege a castle in southern China only to be met by Huang, who fought him to a standstill for several days. It was only because of a ruse that Huang surrendered. Years later, Huang commanded an army against Xiahou Yuan, a feared commander who served Cao Cao. During the Battle of Mount Dingjun, the old general dashed atop his steed, surprising Xiahou Yuan and decapitating him in a single blow.

Yan Yan rivaled Huang Zhong in age and ferocity. Legends have shrouded the pair throughout history, and their sense of duty in the twilight of their years served as an inspiration for papers in Communist China to implore “old men to surpass the fierce Huang Zhong.”

5Walter Cowan

Starting in 1884, when he was a cadet stationed in Nigeria, Sir Walter Cowan enjoyed a long, distinguished career serving with the Royal Navy. He commanded various warships, engaging the enemies of Britain in South Africa during the Boer Wars, in Jutland during World War I, and even in the Baltic Sea monitoring the Bolsheviks after the Great War. By 1931, Cowan had retired, happy to have done his part and planning to spend his remaining years living in comfort.

When World War II erupted, however, Cowan couldn’t ignore the call of duty. He pestered his superiors incessantly to give him the opportunity to serve Britain once more. The 68-year-old pulled a few strings and even accepted a demotion so he could take part in the war effort. In 1941, Cowan was put to work training much younger men in small boat handling. A year later, during the Battle of Bir Hakeim, Cowan was attached to an Indian cavalry regiment captured during the engagement. Legend has it that the old soldier, by then 71 years old, single-handedly fought off an Italian tank, armed only with a revolver.

After Cowan’s repatriation in 1943, you would think he would once again be content to relieve himself of his duty, but he rejoined the commandos and fought in Italy. After a lifetime of military service, he finally retired for good in 1945. Two years later, he became an honorary colonel for the King Edward’s Own Cavalry, a proud distinction bestowed by a cavalry regiment upon a naval officer.

4Jean Thurel

Born on September 6, 1698, Jean Thurel lived to be 108 years old, an incredible age even in this era, let alone in pre-Revolution France. Even more incredibly, he spent over 90 of those years as a soldier.

Since September 17, 1716, Thurel saw action in multiple engagements, wearing his wounds like a badge of honor. In 1733, during the Battle of Kehl, he was struck in the neck by a musket ball, but he managed to survive. During the Battle of Minden in 1759, he was slashed multiple times in the head and face with a saber, yet he still carried on. His brothers and son died in battle, yet Thurel trudged on, content with the life of a simple soldier. During his entire time serving in the army, he was only reprimanded once when he scaled the walls of a fortress at the age of 50 just so he would not miss muster.

In 1787, the Touraine Regiment was ordered to march to the coast to embark on French warships. Thurel, nearing 90 years old, was asked if he would like to ride a carriage. The Frenchman was deeply insulted, stating that since “he had never traveled in a carriage, he would not do so now.” True to his word, he completed the march on foot.

Earning a storied reputation as the oldest soldier in Europe, Thurel served under many French monarchs, including Napoleon Bonaparte, who awarded him with the Ordre National de la Legion d’Honneur and a pension of 1,200 francs. Thurel died on March 10, 1807 after serving 92 uninterrupted years as an infantryman.

3Kas-Tziden Nana

Kas-Tziden, which means “broken foot” in Apache, suggested Nana’s lameness in his left foot and constant suffering from rheumatism. This disability, and the fact that he was 81 years old, meant nothing to the Apache war leader.

Nana of the Chihenne or Warm Springs Apache was born around 1800 and later married the sister of famed tribal warrior Geronimo. They had five daughters, all of whom married tribal chiefs and renowned warriors. It was perhaps his capability in weaving alliances among the various Apache groups that allowed him to form a war band. In 1881, not content to leave the fighting to the younger generation, he led one of the greatest Apache raids the country would see.

Nana and his 15–40 warriors covered 1,600 kilometers (1,000 mi) of enemy territory, from the mountainous regions of Mexico to the plains of the southern United States. Along the way, they fought Mexican and American troops in multiple engagements, killing and wounding dozens of soldiers and capturing hundreds of horses and livestock. For several weeks, the US cavalry chased Nana and his band fruitlessly, never capturing the 81-year-old warrior with the lame foot. The Apache raiders returned to their territory safe and unmolested, bringing unrivaled loot. Nana remained free until 1886, when he was captured while fighting alongside Geronimo, and lived out the rest of his days in peace in Fort Sill, Oklahoma until his death on May 19, 1896.

2Marcus Valerius Corvus

Marcus Valerius was born in 370 B.C. and went on to a glorious career as a politician and commander of Rome’s military. The Romans added the cognomen “Corvus,” or “raven,” to his name in tribute to a particular legend. The story goes that when Valerius was serving as a military tribune in 349 B.C., the Roman army faced off against a larger force of Gauls. A gigantic Gaul, towering over every other combatant, challenged anyone brave enough to a duel, and Valerius obliged. The two fought for what seemed like an eternity with no clear victor when suddenly, a raven unlike anything the Romans had seen before perched atop Valerius’s helmet. The mysterious bird began pecking at the Gaul’s face and arms until Valerius was able to kill him.

Several decades later, at the age of 70, Valerius had already earned a reputation as a skilled statesman and general during the Samnite Wars when he was appointed as Rome’s dictator for a second time after the revolt of the Marsi tribe. He handily defeated the Marsi in battle and captured their fortified towns, quelling the rebellion. He also swiftly crushed a rebellion of Etruscans in a victory so complete that the Etruscans subsequently refused to fight any Roman army led by the notorious commander. As a statesman, he left his mark by passing legislation that expanded the rights of appeal for the common citizens of Rome. He retired after his sixth consulship and lived to be 100 years old.

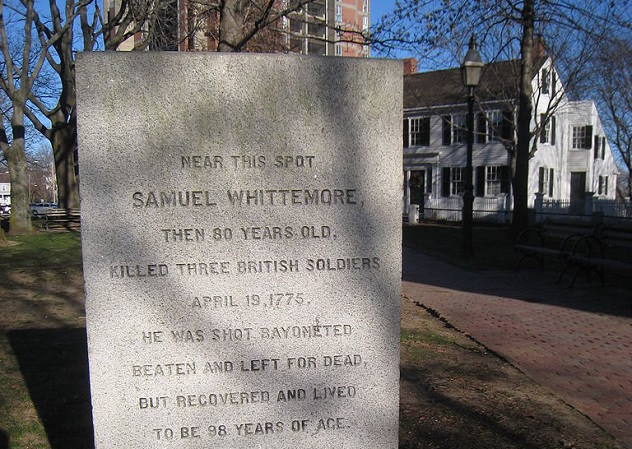

1Samuel Whittemore

Samuel Whittemore was born in England on July 27, 1695 and went on to become a captain for His Majesty’s Dragoons. He saw action against the French in 1745 during the capture of Fort Louisbourg, again in 1758, and as part of the colonial armies during the Indian Wars. After a lifetime of war, the Englishman decided to retire in the colonies, purchasing a farm in what is now Arlington, Massachusetts. He learned to love this new land he called home and the ideals for which it stood.

On April 19, 1775, British forces were regrouping in Boston after the Battles of Lexington and Concord when they were met by a ragtag group of 50 militiamen. Whittemore might have heard the ruckus of the battle, or perhaps the news spread among the townsfolk, but however he was alerted, the 80-year-old farmer sprang into action. He loaded his musket, armed his dueling pistols, and strapped his French saber around his waist before telling his astounded family that he was “going to fight the British regulars” and advising them to remain indoors until it was safe.

Whittemore opened his door to an unbelievable sight: Redcoats marching along the street while minutemen provided inaccurate fire from a distance. He saw his chance when the British were close. He aimed his musket, killing a British soldier. He then drew his dueling pistols and fired at two more soldiers, killing one and mortally wounding another. With no time to reload and the British upon him, he brandished his French saber, slashing at anyone who dared come near.

The British did dare, and much more—one shot him point-blank in the face, while others bayoneted him. They then clubbed the poor farmer in the head and left him for dead. The townsfolk and Whittemore’s family feared the worst, but upon closer inspection, they found him alive and trying to reload his musket despite 13 bayonet wounds, a bloody head, and a torn face. Whittemore was rushed for treatment, and death would have to wait nearly 20 more years to claim him.

News of Whittemore’s courageous stand inspired many, though it took centuries for him to receive his greatest honor. In 2005, Whittemore was declared the State Hero of Massachusetts. Every year on February 3, the anniversary of his death, the state celebrates his legacy.

Jo ain’t an old-timer yet, though he would probably still get his ass kicked by these ones.