Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

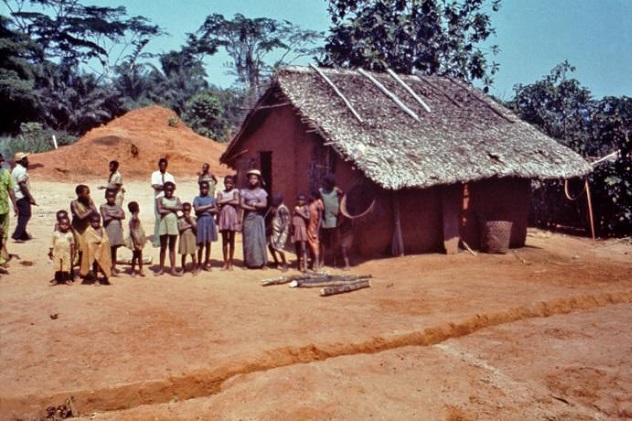

10 Frightening Facts About Ebola

Since it was first discovered in 1976, strains of the Ebola virus have wreaked havoc throughout central Africa, particularly in the Congo area. But previous incidents have only affected a fraction of the people struck down by the outbreak of 2014, which has infected over 1,700 people and killed more than 900. Perhaps the most frightening thing about Ebola, other than its staggering mortality rate, is how very little we know about it.

102014 Outbreak

As of August 6, 2014, the World Health Organization claimed that 932 people had died of Ebola so far in the summer of 2014. In a world of billions, this number may seem statistically insignificant, but it is important to realize that tiny rural communities have been hit especially hard.

On August 5, a nurse in Lagos was the first Nigerian to die of the virus. This is particularly horrifying, as Lagos is the most populous city in Africa, densely packed with an estimated 21 million citizens. Nigeria is scrambling to contain the plague as new cases pop up left and right, but how successful they will be and how many will die remains unknown.

The 2014 outbreak seems to have spread to Guinea, with dozens of cases reported by the Ministry of Health by March 24, 2014. Within a span of months, it managed to cross borders, taking hold in the neighboring nations of Sierra Leone, Liberia, and the Ivory Coast, leading the American CDC to issue a travel advisory against visiting afflicted countries.

9Arrival In America

When news of the 2014 Ebola outbreak first broke, those in the West listened warily but without great concern. After all, Ebola had sprung up intermittently for over 30 years without causing significant damage. But when it was announced that an infected American, Dr. Kent Brantly, would be transported back to the United States, panic ensued. Recognizing a juicy story, the media only made matters worse.

The 33-year-old doctor was transported from Liberia via air ambulance, arriving in the US on August 2, 2014. He was brought to Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, Georgia, which is outfitted with a sophisticated biocontainment patient care unit replete with ultraviolet lights and air filtration systems.

If this does not assuage your fears, experts claim that even if Ebola somehow did make its way out of the hospital and take root in the general population, its impact would be quite minimal. According to epidemiologist Ian Lipkin of Columbia University, “Sustained outbreaks would not occur in the US because cultural factors in the developing world that spread Ebola—such as intimate contact while family and friends are caring for the sick and during the preparation of bodies for burial—aren’t common in the developed world. Health authorities would also rapidly identify and isolate infected individuals.”

8Discovery

The first recorded outbreaks of Ebola occurred around the same time in 1976 in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Sudan. When people began dying of a mystery ailment, William Close, the personal physician of Zaire President Mobutu Sese Seko, sent for a team of experts from Belgium’s Institute of Tropical Medicine. Their research focused on the village of Yambuku, where the first known case infected Mabalo Lokela, the headmaster of the village school, and quickly spread to other people in the village. The Belgian team decided to call the virus “Ebola” after the nearby Ebola River rather than stigmatize Yambuku.

Of course, it is likely that Ebola has infected people much further in the past. Some historians claim that Ebola was responsible for the Plague of Athens, which struck the Mediterranean during the Peloponnesian War in 430 B.C. According to the historian Thucydides, who himself contracted the disease but survived, the plague came to the sea-faring Athenian people from Africa. Evidence is circumstantial, but descriptions of the disease—including its prevalence among caregivers and symptoms like bleeding—do indicate that Ebola may have been the culprit.

7Porton Down Lab Accident

Conspiracy theorists love to spin tall tales of secret government research laboratories where deadly biological agents are cultivated and monsters are bred, but unlike many crackpot theories, this one contains a grain of truth. One such facility is the Centre for Applied Microbiology Research at Porton Down in England, where Ebola research is carried out. The level-four safety category laboratory is outfitted with a shower system to sterilize researchers before they exit and bulletproof glass to ensure the virus is kept securely under wraps. Should an accident happen, such as a tear in a suit or glove, an alarm will sound.

These protocols have been in place for decades, but when Ebola was first making the rounds in 1976, no one was sure exactly what dangers the virus posed. One researcher was accidentally infected at Porton Down on November 5, 1976 when he accidentally pricked his thumb with a syringe while working with laboratory animals. He became ill days later, providing the scientific world with his bodily fluids and much of their initial data about the virus. Luckily, the man survived.

6Sexual Transmission

The first 7–10 days after they begin showing symptoms is critical to the survival of Ebola patients. This is when most Ebola victims die, but if the body manufactures enough antibodies to fight off the virus, recovery is possible. Even after a clean blood test, though, Ebola can linger in strange ways, such as in the breast milk of lactating women. It also stays in semen for up to three months, as blood-borne antibodies don’t reach the testicles, so men who recover from Ebola are told to practice safe sex with condoms. Seminal fluid taken from the researcher from Porton Down contained the virus 61 days after his recovery.

Experts state that likelihood of Ebola spreading through sexual contact is minimal, particularly because those with high viral loads are in no condition to be amorous. A more likely, if infinitely more morbid, route of transmission is the African custom of washing corpses before burial. While Ebola thrives in living bodies, the virus has been found in the carcasses of apes that have been dead for several days.

5Effect On Wildlife

Viruses that quickly kill their victims naturally fill us with terror, but these are hardly the most insidious. Death within a manner of days is scary, but it is a terribly ineffective way to spread a disease. Fast-acting viruses like Ebola have historically burned themselves out quickly and close to their original source, whereas viruses that manifest slowly, such as HIV/AIDS, have spread across the globe.

Scientists believe that the reason Ebola keeps managing to pop up is that the virus has found a reservoir in the bat population of central and western Africa, in the same way that bats have become the vector for rabies in other parts of the world. The fruit bats, which are asymptomatic, transmit the disease to animals like the duiker (a small antelope) and primates like chimpanzees and gorillas.

In more economically advantaged parts of the world, these creatures would quickly perish, and the story would be over. However, in many parts of sub-Saharan Africa, there is brisk trade in “bush meat,” wild animals that are hunted and sold when less palatable options are unavailable. Bush meat can be nearly any species, including bats, monkeys, and rats. While this sounds revolting to many of us, it is a far superior option to starving to death. It would have only taken a single infected animal being eaten to start the entire 2014 contagion.

4How Ebola Kills

Although the plague thus far appears localized, hospitals the world over are on high alert for the symptoms of Ebola. Unfortunately, symptoms of the early stages of the virus are so common that they are frequently ignored or misdiagnosed. The initial symptoms are quite like a cold or flu: headache, exhaustion, body aches, fever, sore throat, etc. Usually, these kinds of things might portend an ugly few days but are unlikely to send anyone scrambling for the nearest emergency room.

Unfortunately, things get far worse from there. The stomach soon revolts with vomiting, diarrhea, and wracking gastrointestinal pain, leaving the patient weakened for the next stage, in which the virus attacks all the systemic functions in the body. This is the most gory part, when the “hemorrhagic” element of the fever becomes apparent. Internal bleeding is common, the skin breaks out in blisters, and blood pours from the ears and eyes.

Death itself comes from various complications, including seizures, organ failure, and low blood pressure. There are several factors involved in determining the mortality rate, including the specific strain of the virus. The death rate of the 2014 outbreak hovered just above 60 percent as of August.

3Vaccine

In the past, Ebola spread from its animal hosts, typically infecting a handful of people in rural areas before fizzling out. While frightening and great fodder for thrillers like 1995’s Outbreak, whose plot revolves around a fictional form of the disease, it didn’t arouse a great deal of concern in the West. Developing a cure or vaccine has not historically been a financially viable option for pharmaceutical companies, since there would be no profit in it.

Despite the lack of commercialization potential, the world’s governments have been taking the disease seriously for years, sinking millions of dollars into research on how to stop Ebola if it were to be used as a biological weapon. Some experimental vaccines have shown great promise, including one that completely prevented rhesus monkeys from becoming infected with the Zaire strain, the one responsible for the 2014 outbreak. This vaccine is so effective that it even cured four monkeys that had already been infected. However, interesting private industry in making this a reality for the masses is an altogether different hurdle.

2Transmission

The precise mechanisms of the transmission of Ebola are unknown. Most experts agree that it can only be passed among humans through the exchange of bodily fluids, though there is some discussion that it may be spread aerobically from pigs to other species. At first glance, it seems easy to insulate oneself from such a virus, even for primary caregivers, by limiting the transfer of fluids.

Unfortunately, those who haven’t witnessed the ravages of Ebola firsthand are all too quick to underestimate exactly how much fluid leaks from the body of an Ebola patient, particularly in the latter stages, when blood can leak from every orifice. Combined with the fact that a single nurse or doctor is often charged with attending to dozens of patients at a time and the generally poor medical infrastructure of central and western Africa, it is no surprise that clinicians often find themselves sick.

1Treatment

In the past, treatment of the Ebola virus was practically nonexistent. Sufferers were only given palliative care, including liquids and electrolytes to keep them hydrated, painkillers like ibuprofen to bring down fevers, and antibiotics to temper any other complications and keep the immune system strong enough to focus on fighting the virus. The rest was largely up to the individual’s own constitution and which strain had sickened them.

However, the American victims, Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, have received some experimental medicine. Brantly was treated early on with a blood transfusion from a 14-year-old boy he had treated who had recovered from the virus. They were also administered a serum pioneered by San Diego’s Mapp Biopharmaceutical derived from the antibodies of animals exposed to Ebola. The serum is supposed to spike the immune system and has reportedly proven effective in improving Brantly and Writebol’s condition. Other companies, such as Vancouver-based Tekmira Pharmaceuticals and Fujifilm’s US partner MediVector, have also been fast-tracked to develop Ebola treatments before it is too late.

Mike Devlin is an aspiring novelist.