Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Unintentional Mass Killers

The road to hell is paved with good intentions. You’ve probably heard that before, and it means that sometimes your best efforts can fail horribly. Even people who you’d fully expect to be evil all the time try to do good—and sometimes that blows up in their faces. Even the best of plans can lead to disaster and untold death.

10Walter Duranty

Walter Duranty was head of the New York Times Moscow bureau for four years in the early 1930s. At best Duranty was overly soft on communism, at worst he was a propagandist who deliberately covered up the starvation of millions.

Duranty was in Moscow during the period known as the Holodomor, when the Soviet Union deliberately starved at least two million Ukrainians to death (other estimates are as high as 12 million). In a November 1931 article, Duranty reported that “there is no famine or actual starvation nor is there likely to be.” By that point at least 500,000 Ukrainians had already been displaced from their homes and thousands were dead.

In 1933, when it was painfully obvious that the famous “Soviet Bread Basket” of Ukraine was losing 30,000 people a day, Duranty claimed that “there is no actual starvation or deaths from starvation, but there is widespread mortality from diseases due to malnutrition.” In a 1933 dispatch, Duranty insisted there was no famine, just mild, unavoidable hunger, concluding, “to put it brutally—you can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs.” In 1932, Duranty received a Pulitzer Prize for his “top notch” reporting on life in the Soviet Union.

Had Duranty even hinted at the true horrors of the famine, world outrage might have saved millions. The New York Times later admitted that Duranty’s reporting was horribly erroneous, but the Pulitzer board refuses to withdraw his award, concluding that Duranty had not intended to mislead his readers.

9Mary Mallon

The name might not ring a bell, but her nickname should. “Typhoid” Mary Mallon emigrated from Ireland in the 1880s and found work as a cook for wealthy families in New York. But despite her reputation as a great cook, it seemed that everyone she worked for became sick or died.

It wasn’t until 1906, when she infected the family of Charles Warren at his summer home on Long Island, that the outbreaks of disease were directly tied to Mary. Deadly cases of typhoid fever were traced all the way back to Mary’s 1900 employment in Westchester County, and the legend of Typhoid Mary began. Mary herself went into complete denial, protesting that she herself had never been sick. In a 1909 letter, written while quarantined on an island in the East River, she claimed: “There is nobody on this island that has typhoid. There was never any effort by the Board authority to do anything for me excepting to cast me on the island and keep me a prisoner without being sick nor needing medical treatment.” The extent of Mary’s denial is shocking—she chased officials away with a fork when they first inquired about her disease and later jumped from a window to escape the health department.

In 1910, after she somehow retained a lawyer, the New York City Health Commissioner relented and agreed to release Mary—on the condition that she never work as a cook again. And Mary Mallon never did. However, a certain Mary Brown soon began infecting families across the city. A quick investigation confirmed Brown was really Mallon under an new name, culminating in her re-quarantining in 1915. She remained in isolation until her death in 1938.

An autopsy confirmed that Mary was indeed the deadly carrier doctors had feared—her gall bladder was teeming with bacteria. Over 50 people were infected by Typhoid Mary and at least three died. Mary herself went to her grave insisting that she couldn’t be the cause of the illness surrounding her—since she had never been sick, she couldn’t believe that she carried the disease. In 2013, scientists discovered that certain strains of typhoid-causing salmonella can survive in an outwardly healthy person, solving the last mystery of Typhoid Mary.

8Gaetan Dugas

Dugas isn’t widely-known, but his nickname is arguably more infamous today than Typhoid Mary—he was “Patient Zero,” a name given to him in And the Band Played On, Randy Shilts’s groundbreaking book on the early fight against HIV and AIDS. According to some early accounts, Dugas, a highly promiscuous Canadian flight attendant, was the original source of the AIDS epidemic in America.

New research has completely discredited the idea—AIDS likely existed before Dugas was even born in 1953, and the earliest known American case was in the late ’60s. Even Shilts knew the idea of Dugas as Patient Zero was highly questionable, and had to be talked into including it by his editor, who insisted the salacious angle would help draw attention to the growing epidemic. The book’s infamous story of Dugas admitting that he had “Gay Cancer” after having sex with a man is likely a flat-out lie.

But Dugas isn’t completely off the hook. He is known to have had sex with at least 40 other people who contracted AIDS. There is no way that one man was responsible for spreading AIDS in America. But the fact that Dugas knew he had “something” and still continued to have sex with up to 250 partners a year (his estimate) is undeniable. He wasn’t the cause of the US AIDS epidemic, but he did at least semi-knowingly spread the disease to other unsuspecting gay men.

7Mao Zedong

Of course, as a brutal dictator, Mao intentionally killed a horrifying number of people. But one of the darkest periods of his rule wasn’t really supposed to kill anyone. In the late 1950s, Mao knew that the Chinese economy desperately needed modernization. But his move to bring China up to date backfired horribly—and ended up killing millions.

In an attempt to transition from an agricultural to an industrial society, the Chinese government forced peasant farmers into collective communities, with the eventual goal of moving them into jobs such as steel production. Homes were destroyed and turned into fuel to power steel plants. Perhaps most bizarrely, the government decided that agriculture itself could be reorganized along communist lines. “Happy plants grow together,” Mao once said, so the remaining farmers were forced to specifically plant crops as the government told them. The result was a devastating famine—as many as 35 million Chinese died during the “Great Leap Forward.”

However, not all died of starvation—millions were murdered for not following with the government’s plans. Over 500,000 had been executed by 1958 alone, and that was the infancy of the program. China has never officially acknowledged the existence of the famine.

6Kim Jong Il

Speaking of dictators, Kim Jong Il proved that he was just as bad of a farmer as Mao. North Korea knew they were in significant financial trouble when the Soviet Union fell, so Kim Jong Il figured he could stimulate the economy with an agricultural boom.

The problem began with massive flooding in 1995, which destroyed huge swaths of farmland. The North Korean regime responded by double-cropping fields, which led to soil depletion, and also overused chemicals to try and speed up the growing season. The result was a disaster, and in a country where only 20 percent of land was farmable and private farms were illegal, revamping the land would be no easy task. The country already had a “let’s eat two meals a day” policy in place since 1991, but that quickly became “let’s eat two meals a month.”

Unlike China or the Soviet Union, at least North Korea admitted people were starving. The famine killed between 250,000 and 3.5 million people. Countries such as the US, South Korea, and China came to their aid, but the damage still isn’t close to being undone. To this day, North Korea relies heavily on foreign assistance to feed their people.

5Unnamed Mechanics

In the early days of air travel, it was common for a flight to make numerous stops along a route. In 1961, Northwest Orient Flight 706 took off from Milwaukee, with stops scheduled in Chicago, Tampa, Fort Lauderdale, and Miami. Everything seemed normal as the plane prepared to take off on its second leg from Chicago. But shortly after beginning its liftoff, the plane banked sharply to the right, struck some power lines, and crashed to the ground, killing 37 people.

The plane was fine on the first leg of the trip, so what happened? A few months earlier, the plane had undergone a routine safety inspection. While working on the left wing, mechanics replaced the hydraulic boost system that controlled the plane’s ailerons. Tragically, the mechanics failed to properly tighten the connectors on the new system. Over time, the natural shake of the plane further loosened the screws. Finally, the connectors fell off entirely and the plane could not be controlled. The error happened between the maintenance crew’s second and third shifts.

It wasn’t the first flight to crash due to a maintenance error—but it was the first that didn’t crash directly after the work. The actual individuals were never named publicly. As of 2007, around 12 percent of all airline crashes have involved maintenance errors.

4Lillie Colvin

In 1962, at Binghamton General Hospital in upstate New York, an odd thing occurred. Newborns were becoming sick. The infants seemed to be feeding normally, leaving doctors flummoxed as seven babies died in quick succession. It’s very likely that more would have perished if a nurse named May Pier hadn’t broken hospital rules and fixed herself a cup of coffee in the formula room. Pier only had to take one sip to discover the problem—someone had accidentally confused salt with the sugar intended for mixing baby formula. Adults will usually pull away from something too salty, but newborn babies have no such reaction. Salt dehydration isn’t common, but it can be deadly.

Outrage raced through Binghamton. The hospital received numerous threats, including a bomb scare that led to guards being placed at the hospital entrance. How could such a shocking error occur? To save money, the hospital would purchase bulk canisters of salt and sugar, which were then used to fill smaller containers on the counters. Shortly before the spate of deaths, Lillie Colvin, a pregnant Licensed Practical Nurse (and mother of three), went to the basement where the canisters were kept and filled the smaller containers. The large salt and sugar canisters were stored next to each other.

Colvin never faced charges for the deaths of the infants, and the hospital stood by her, calling her a “good employee.” Colvin herself maintained her innocence, insisting she had properly filled the sugar container from the right canister. However, there was no evidence of anyone but Colvin filling the containers. The hospital eventually settled financially with the families. Each received $7,000 for the loss of their child. After that, the deaths simply faded out of the public consciousness.

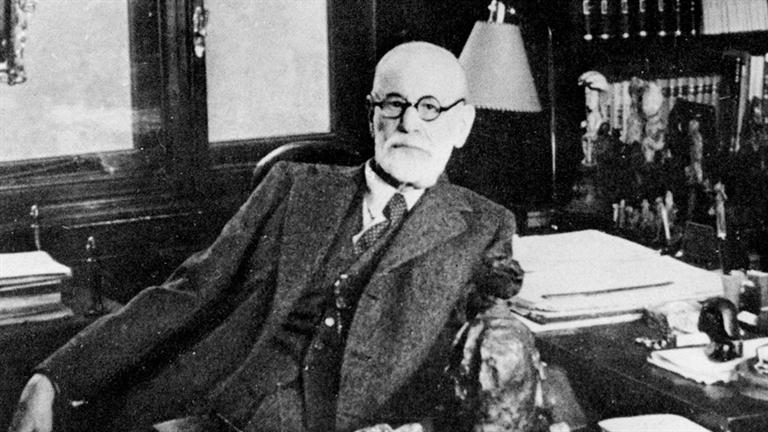

3Sigmund Freud

Before he became the father of modern psychoanalysis and embarrassing conversational slips, Sigmund Freud was a simple doctor with an interest in the workings of the brain. Then, while working at Theodor Meynert’s Psychiatric Clinic, the young Freud became interested in cocaine.

Cocaine products were already freely available. In 1863, chemist Angelo Mariani had invented something called coca wine, which is exactly what it sounds like. But it was Freud who really pushed cocaine’s reputation as a wonder drug. He eventually became the world’s leading expert on the drug, and prescribed it to patients as a cure for pretty much everything—but especially to stimulate the brain. In 1884, Freud published his highly successful work Uber Coca, which sang cocaine’s praises.

Cocaine quickly grew in popularity—if anyone doubted its magical abilities, its advocates could point to the medical reports of Dr. Sigmund Freud, who reported, “the toxic dose (of cocaine) is very high, and there seems to be no lethal dose.” Unfortunately, he was wrong. One of his patients, Ernst von Fleischl-Marxow, would eventually die from the effects of cocaine abuse. You obviously can’t pin every cocaine death from 1884 until today on Freud, and von Fleischl-Marxow was the only direct death he was involved in, but Freud truly believed for a time that cocaine was the answer to all the world’s problems. Many an addict followed the good doctor’s advice.

2Toyota

Toyota sold over 1.2 million Corollas worldwide in 2013, making them the most popular car makers in the world. Much of Toyota’s success comes from their reliable reputation. But a few years ago, a spate of deadly acceleration issues threatened to destabilize the entire company. In many Toyota models, the floor pedal, brake, and floor mat didn’t fit together well, allowing the accelerator to become trapped under the mat.

It’s unfair to pin all the acceleration deaths on one single person, but someone in Toyota’s floor mat department approved a dangerously poor design. As many as 89 people died and over 6200 complaints were filed. An initial recall of five million vehicles failed to fix all of the problems, with some consumers still reporting sudden acceleration, including one case that a Toyota dealership confirmed had nothing to do with the floor mat. The end result was a costly one: Toyota paid $1.2 billion in fines and recalled eight million vehicles.

1Horace Lawson Hunley

How does someone intending to kill people become an accidental killer? Welcome to the complex tale of Horace Lawson Hunley, a lawyer and inventor with a keen interest in building submarines. During the US Civil War, Hunley joined the Confederates. He built his first military submarine in New Orleans, but the sub was scuttled when the North took the city.

Undeterred, Hunley moved to Charleston, where he built another submersible, the vaingloriously named H.L. Hunley. The sub was intended to be the answer to the Union naval blockade threatening the city. Hunley watched from the shore as a nine-man crew tested his new vessel. But as the sub was lowered into Charleston Bay, water poured into the unsecured hatch, drowning five crewmen. A bit over a month later, in October 1863, a second voyage was undertaken. This time, Hunley decided to take command himself and the sub successfully dove beneath the surface of the bay. It failed to come back up. Hunley and seven other submariners died.

The Confederates eventually pulled the sub from the bottom of the bay, where it was stuck nose-first in the silt, and got it ready for one more run. In 1864, the Hunley finally succeeded in launching an attack, sinking the USS Housatonic. Five Union sailors died in the sinking. And then another eight Confederate sailors died aboard the Hunley, which was a mere 6 meters (20 ft) away from the Housatonic when it blew up, suffering catastrophic damage as a result. In all, Hunley’s deathtrap took out 21 Confederates and five Yankees, not exactly the mass killing he was hoping for.

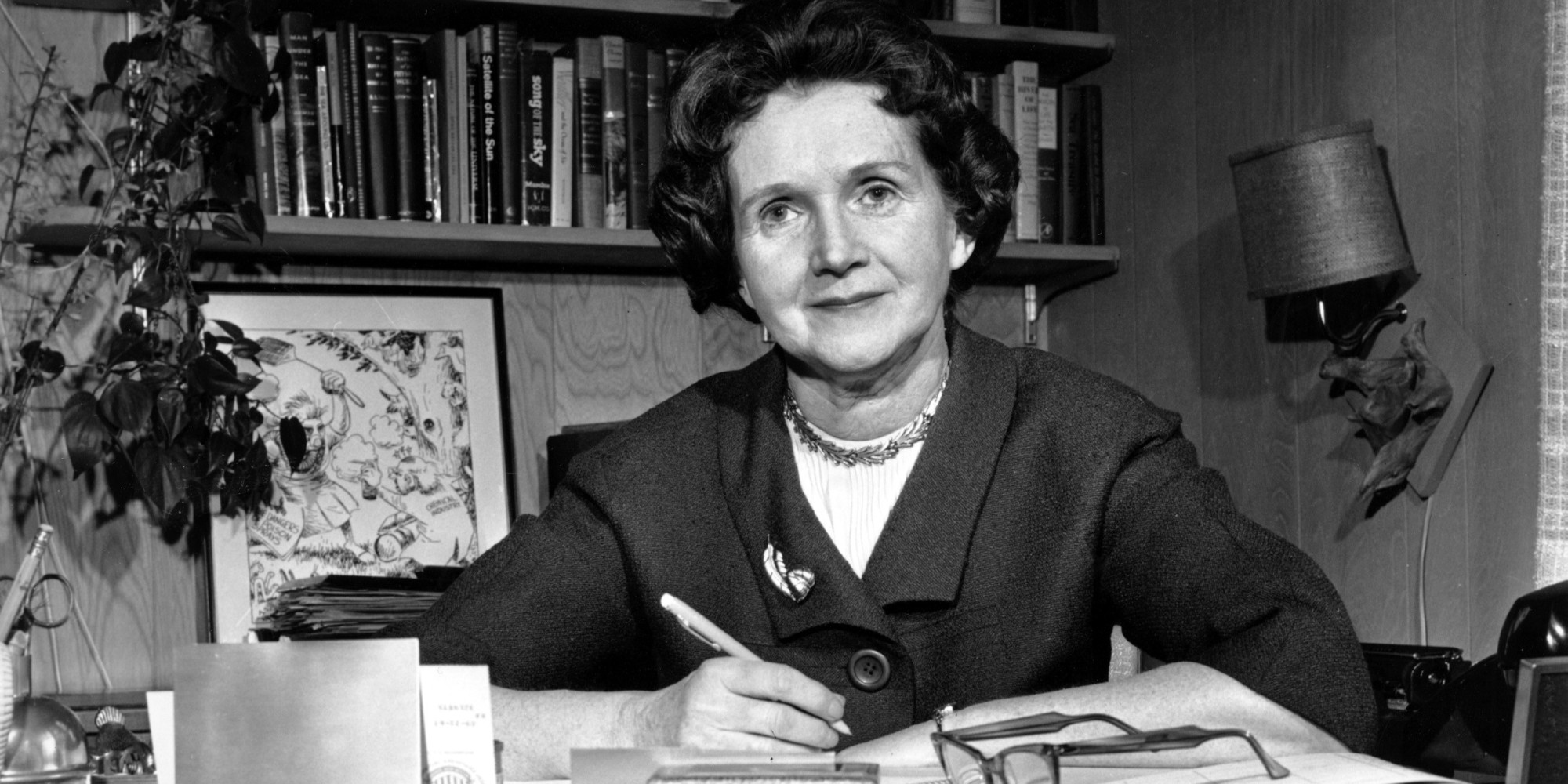

+Rachel Carson

Rachel Carson was a hugely influential marine biologist best-known for her 1962 book Silent Spring, which became something of a bible for the environmental movement. The book strongly criticized the insecticide DDT, which was widely used in eradicating mosquitoes, among other pests. Silent Spring became a huge bestseller on its release in 1962, and played a major role in changing the public perception of DDT, which soon began to be banned across the world.

What many people do not realize is that DDT had already saved tens of millions of lives by 1962—perhaps even hundreds of millions. Beginning in the late 1950s, the World Health Organization’s Global Malaria Eradication Program deployed thousands of tons of DDT in the largest mosquito eradication program the world had ever seen. The results were astonishing. Before DDT had been developed, the fight against malaria had almost seemed a losing battle. Now, the disease was eliminated in Taiwan, the West Indies, northern Australia, and much of North Africa. Before DDT, around 800,000 people died of malaria in India every year. By the early 1960s, the number of fatalities had dropped to zero.

Nor was the case against DDT quite as bulletproof as it might seem. Despite some claims, there is still no clear evidence that DDT can cause cancer in humans. Entomologist J. Gordon Edwards, probably Carson’s most caustic critic, has claimed that: “This implication that DDT is horribly deadly is completely false. Human volunteers have ingested as much as 35 milligrams of it a day for nearly two years and suffered no adverse effects. Millions of people have lived with DDT intimately during the mosquito spray programs and nobody even got sick as a result.” According to a professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: “There is no convincing evidence that DDT, as used indoors against malaria mosquitoes, has caused any harm to humans.”

It’s not fair to blame Carson for every malaria death since Silent Spring. DDT’s effectiveness was decreasing anyway, as mosquitoes with a genetic resistance to the chemical became dominant. New insecticides proved quite effective in dealing with the disease. And most countries merely banned DDT as an agricultural pesticide, while still permitting its use as a public health tool. Concerns over DDT’s agricultural were arguably justified—it takes a ton of DDT to dust a cotton field, but only a few grams to rid a home of deadly mosquitoes.

But since Carson’s book soured the public image of the chemical, tropical countries have come under increased pressure to stop using it in mosquito eradication programs. Often, the pressure has come from wealthy Western nations where malaria is non-existent. In the 1990s, malaria rates shot up across South America as aid organizations pressured developing countries to avoid the use of DDT for any reason. In Ecuador, where DDT use to control disease was increased, the incidence of malaria fell by 60 percent. There are genuine concerns over DDT’s safety, its effectiveness has waned since its heyday in the ’50s and ’60s, and there are now alternatives in the fight against mosquito-borne diseases. Yet it is likely that at least some people have died in part because of Silent Spring and its campaign against the chemical.

Jake wrote a trivia e-book filled with crazy stuff like the kind you just read in this list. You can follow him on Twitter for more useless facts.

![11 Lesser-Known Facts About Mass Murderer Jim Jones [Disturbing Content] 11 Lesser-Known Facts About Mass Murderer Jim Jones [Disturbing Content]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/jonestown2-copy-150x150.jpg)