History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Influential Slaves Who Deserve To Be More Famous

Far too many slaves have escaped recognition simply because they were unable to read or write. We’ve covered some of their stories in the past, but plenty more also deserve their time in the spotlight, especially for their contributions to art, literature, medicine, and humanity.

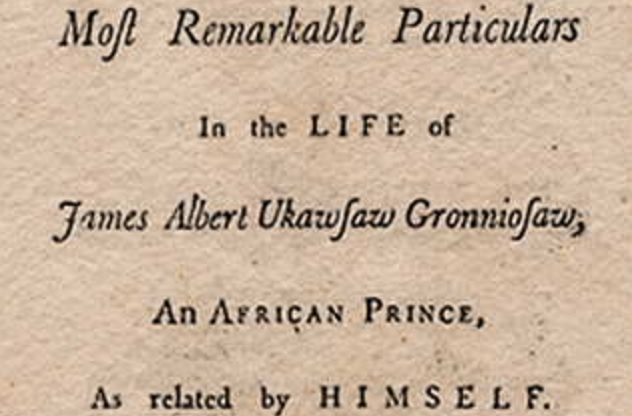

10Ukawsaw Gronniosaw

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw began his life in what is today Nigeria. As a young child, Gronniosaw was lured away from his village by slave traders who promised to show him “houses with wings to them (that) walk upon the water.” These “houses” turned out to be slave ships, and Gronniosaw was sent to New York and purchased as a slave there.

His master, a minister named Theodore Frelinghuysen, ensured that he received a religious education. When Frelinghuysen died, Gronniosaw was freed—he remained at the Frelinghuysen home, however, serving the late minister’s wife and her children until they too passed away.

At that time, Gronniosaw decided to go to England, where he married a white woman. The couple worked hard to keep their children fed, and Gronniosaw published an autobiography to contribute to their meager income. His book, A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Grunniosaw, an African Prince, first appeared in 1772. Grunniosaw is heralded as the first former slave to publish his life story, shedding light on the awful circumstances of slavery that had, until then, been largely unknown by everyday people.

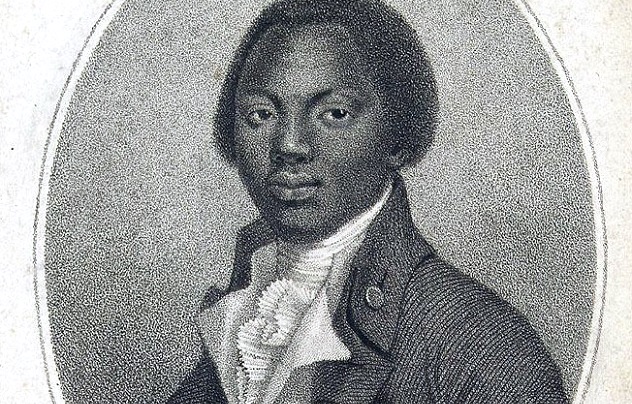

9Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano was born to a respected Ibo village leader in the mid-1700s. At the age of 11, he was captured and forced into the slave industry. After surviving the harrowing Middle Passage and making it to Virginia, Olaudah was sold to a naval captain named Michael Henry Pascal, who took him to England. He learned to read and write there, and also became a skilled ship crewman, accompanying Captain Pascal on many voyages around the world.

After about five years, Pascal sold Equiano to Robert King, a merchant from Philadelphia. King was kind to Equiano, and by working hard and trading, Equiano was able to buy his freedom from his master. After becoming free, Equiano continued to work as a sailor, but his pursuit of a career was not without struggle. On one occasion, a ship captain ordered that Equiano be bound by the ankles and wrists and strapped to the ship’s mast, where he hung all night long. They only released him the following morning because he was blocking the sails.

Equiano eventually traveled back to England, where he became a public speaker and activist. He formed an abolitionist group called the Sons of Africa, and petitioned Parliament to condemn the practice of slavery. In 1789, he published his autobiography, The Life of Olaudah Equiano, which became an immediate best seller.

8Jupiter Hammon

Jupiter Hammon was born to slave parents in Long Island, New York in October of 1711. Though his father was rebellious and had tried to escape numerous times, Jupiter was quite loyal to his slaveholders. He frequently accompanied his master on business trips, eventually donning the hat of house bookkeeper.

Having found such favor with his master’s family, he was allowed to attend school and quickly became an accomplished writer. He published a number of works while remaining a slave, the first of which was 1760’s Elegy on the Death of Whitefield.

Hammon seems to have realized that slavery was a deeply embedded component of American culture and economics at the time, and thus was not something that could be done away with quickly or easily. He addressed this belief extensively in his writings as well as his interactions with fellow slaves. In 1784, at age 76 (and still a slave), Hammon further promoted this message at an African Society meeting. There, he gave a rather depressing speech exhorting his fellow slaves to remember God and to serve their masters dutifully, for whether it was fair or not, slavery was their lot in life. His speech later came to be known as the “Hammon Address.”

7Absalom Jones

Absalom Jones was born in 1746 in Sussex County, Delaware. Both of his parents were slaves, so an education was a privilege not bestowed upon Jones. He taught himself to read, however, by buying books with pennies given to him by his master’s visitors. In 1770, Jones married a fellow slave, Mary Thomas, and purchased her freedom later that year (although he was unable to purchase his own until 1784).

Jones and his close friend, Richard Allen, were active members of St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia. Due to community outreach, the black congregation actually doubled in size during Jones’s tenure. This was ill-met by white churchgoers, who tried to segregate one Sunday in November 1786. Jones and his fellow congregants, refusing to be ushered onto the balcony, left the building in a historic walkout.

Jones went on to become priest of the St. Thomas African Episcopal Church—this was the first black Episcopal parish in the colonies, which made Jones the first priest of African descent in the United States.

6Lucy Terry

Lucy Terry was kidnapped from Africa at a young age and brought to Massachusetts as a slave. She was purchased by Ebenezer Wells and brought to live in the small town of Deerfield. Wells was a tavern owner who seemingly integrated Lucy into the family—he even went so far as to have her baptized at the age of five.

Lucy was serving the Wells family when, in 1746, the nearby Abenaki tribe attacked Deerfield. The 21-year-old Lucy, known for being gifted at storytelling, composed a poem called “The Bars Fight” directly after the incident. Although it wasn’t published until 1819, it’s still heralded as the most famous account of the attack.

Lucy remained a slave to the Wells until 1756, when she married a free man named Abijah Prince. Soon after, Lucy was freed either due to her own hard work or her husband’s pocketbook. The Prince family settled in Vermont, where Lucy had six children and remained an active voice in her community—in 1803, she successfully presented a land appeal before the Virginia Supreme Court.

When Lucy Terry passed away, the Vermont Gazette printed her obituary—a gesture unheard of for a woman (let alone a former slave) at the time. Her obituary was even reprinted in a Massachusetts newspaper, showing that Lucy Terry’s influence in her former state had not been forgotten.

5Ignatius Sancho

Ignatius Sancho was born in 1729, either onboard a slave ship or just after it landed in the Americas. At any rate, Sancho was enslaved in Grenada until he was two years old, at which point he was taken to England with his master.

Later in life, Sancho became a free man. It’s unknown exactly how this happened, but it’s assumed that he was granted liberty upon his master’s death. He soon persuaded a powerful man—the Duke of Montagu—to hire him as a butler. In this employment, he taught himself to read and write, eventually becoming adept as a playwright and composer.

When the Montagus passed away, they left him a small amount of money—this was beyond generous given the social circumstances at the time. Sancho used this purse to buy a grocery shop in Westminster, which he and his wife operated. This shop became a hub of anti-slavery sentiment as well as a meeting place for many famous politicians and activists. Sancho, as an independent householder, is in the record books as the first black person of African origin to vote in an election, doing so in 1774 and 1780.

He was regaled as an “extraordinary Negro” of his day, and his legacy lived on after he passed. In 1782, two years after his death, a collection of his letters was published and later used in the fight to end slavery.

4John Anderson

John Anderson was known as Jack Burton for much of his life, as he worked as a slave for Moses Burton in Fayette, Missouri. In 1850, Jack married a slave named Marie Tomlin who lived near the Burton plantation. Jack visited Marie often but, in 1853, Jack was sold to an owner in Glasgow, Missouri—a distance considerably farther from Fayette.

One night, he secretly made the illegal journey to visit his wife and three children. He was soon discovered by a farmer named Seneca T.P. Diggs, who threatened to reveal his crime. Panicked, Jack killed Diggs and ran for his life. He ended up in Canada, changed his name to John Anderson, and began working as a laborer in the town of Hamilton. In 1854, the United States government’s request of Anderson’s extradition was denied by the governor general of British North America. However, six years later Anderson was thrown in jail by a small-town magistrate and charged with murder.

At this point, a Hamilton lawyer—appropriately named Samuel B. Freeman—got involved. Freeman successfully pleaded Anderson’s case and he was released, but not for long. Less than six months later, Anderson was pursued by a Detroit detective named James A. Gunning who saw that he was imprisoned again. The court ruled that Anderson had indeed committed murder and could be extradited, though there was a small window of time before that could occur. Within that window, angry abolitionists rallied for Anderson’s defense and even wrote to the Anti-Slavery Society in London.

In a groundbreaking legal move, Anderson was granted a writ of habeas corpus from a British court, and in 1861 he was released. This whole debacle resulted in the British Habeas Corpus Act of 1862, which prohibited writs of habeas corpus from being administered to any foreign territory where a legal system was set in place. As if changing legal precedent wasn’t enough, Anderson went on to speak at over 25 anti-slavery gatherings in London.

3Mary Prince

Mary Prince was born a slave in Bermuda in 1788—shortly thereafter, she was sent to work in Antigua. She was treated horribly during her early years, suffering numerous beatings at the hands of her cruel masters. In 1826, she married a former slave named Daniel James, who had purchased his freedom and worked as a carpenter in the town. He was free to marry as he wished, but Mary was brutally beaten for marrying without her master’s permission.

Within two years, her owners decided to move to England, taking Mary with them. Once abroad, Mary began campaigning openly for her freedom. She even presented an anti-slavery petition to Parliament, becoming the first woman to ever do so.

She was eventually able to escape but couldn’t return to her husband in Barbados. She continued her fight against slavery until her death, becoming involved with the Anti-Slavery Society and publishing an autobiography. (This was another major accomplishment, as no black woman had ever written or published her life story before.) Prince’s book grew to be an important reference for proponents of the abolition movement, and her firsthand accounts of the cruelties of slavery were eye-opening for colonists who had—up until then—ignored the practice’s realities.

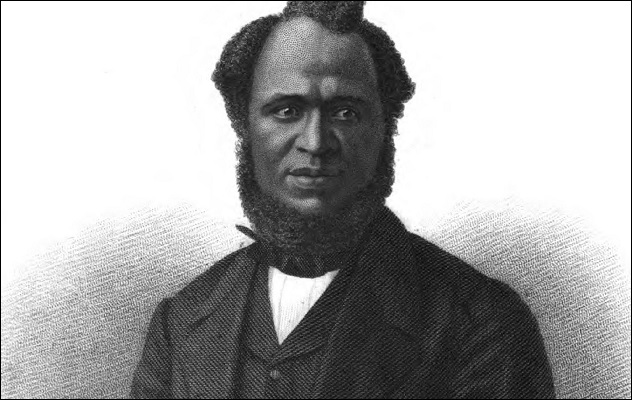

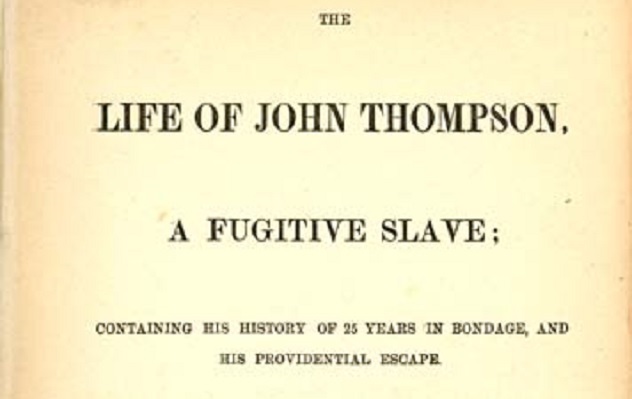

2John Thompson

John Thompson was born into slavery on a plantation in Maryland in 1812. His master, John Wagar, was a violent man who ordered his slaves whipped regularly to ensure their “humble submission.”

When Thompson was 12, Mr. Wagar’s wife (who was apparently the owner of the property) passed away, and the land was divided among family members. Thompson and his family were sent to work for George Thomas, an experience that was no less miserable than the one under Wagar. At one point, Thomas’s son, Henry, beat Thompson so intensely that he was laid up and unable to move for five weeks.

Thompson was lent to a family member, Richard Thomas, who eventually discovered that Thompson had secretly been learning to read and write for years. Richard threatened to sell Thompson “down-river” (the dreaded term for the incredibly brutal plantations of the Deep South) when he learned of this ability. Rather than endure Hell on Earth, Thompson decided to make a break for it and escape. He and a friend managed to make it all the way to Pennsylvania, dodging all kinds of obstacles along the way including slave catchers and their dogs. At one point, the two of them even had to steal a pair of horses and assemble grape vines into bridles to escape.

Once in Pennsylvania, Thompson married and began working. However, when fugitive slaves in the area were arrested and sent back to their masters, Thompson decided that the safest place for him was at sea. He boarded a whaling vessel and quickly became a skilled whaler, only returning home after several years at sea.

Thompson’s autobiography, The Life of John Thompson, A Fugitive Slave, offers amazing insight into the life of a slave and a later world traveler.

1James Derham

James Derham was born a slave in Philadelphia but was one of the fortunate few who was taught to read and write by his masters. Owned by a series of doctors, Derham also picked up on the practice of medicine. He was eventually bought by a Scottish physician in New Orleans who encouraged him to further explore his interest in the field. Eventually, Derham was performing medical services on his own.

Sometime in the late 1780s, Derham earned his freedom (whether he purchased it or his master willingly bestowed it on him, nobody knows) and began working as a doctor for free black people and slaves in the New Orleans area. He quickly earned a reputation as a remarkable physician, and in 1788 he was even recognized by Dr. Benjamin Rush (whose signature is on the Declaration of Independence). During the yellow fever epidemic of 1789, Derham successfully treated all but 11 of his 64 patients—an extremely successful ratio given the era and mortality rate of this disease.

Unfortunately, new laws passed in 1801 required doctors to have earned a degree; this restricted Derham from continuing his practice, since he did not have one. Derham disappeared in 1802, and no records of what he did afterward exist. Despite his influence being cut short by the new law, Derham remains a source of inspiration—he is still recognized as the first African American to practice medicine in the United States.

Tera is a Utah native who enjoys camping, whiskey, and reading books in hammocks. Email: [email protected].