Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

10 Of The Strangest Church Relics On Public Display

People think of churches and other holy sites as peaceful places full of sunshine and fresh air, totally safe and perhaps a little bit dull. But saving souls is serious business to some, especially before the modern age. Furthermore, the business of building sacred sites upon the ruins of pagans can leave behind some unusual ghosts.

From a spring dedicated to a pagan virgin goddess to churches made almost entirely out of human bones, here are holy places that wanted to make sure you get their message and don’t mind creeping you out to do it.

10Crypt Of The Chiesa Immacolata Concezione

Rome, Italy

This 17th-century church was built by Cardinal Antonio Barberini, a Capuchin Franciscan and brother of Pope Urban VIII, and was designed by Franciscan friar Michele da Bergamo. It houses several high-profile tombs and famous paintings, but its greatest attraction is the chapels in the lower levels.

Five subterranean chapels contain the remains of 4,000 Capuchin friars and poor Roman citizens from the 17th century onward, laid out in an artistic fashion. It took 300 trips from 1627–1631 to cart the carriages filled with bones and mummified remains into place. The earth covering the pavement of the cemetery is said to be from the Holy Land, and a memento mori inscription near the exit reads, “You are what we have been. You will be what we are.”

The remains are arranged in elaborate mosaics and built up into columns, arches, or floral designs. The crypts are even arranged based on the type of bone. There is a Crypt of Skulls, a Crypt of Pelvises, a Crypt of Leg and Thigh Bones, as well as the Crypt of the Resurrection (with a centerpiece painting of Jesus summoning forth Lazarus), and a Crypt of the Three Skeletons (a highly symbolic diorama that reflects on death).

9Basilica Of Santa Croce In Gerusalemme

Rome, Italy

Also known as Heleniana or Sessoriana, The Basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme (Holy Cross in Jerusalem) stands on what was part of a residential complex owned by Emperor Constantine in the third century. It was once part of the Sessorian Palace, owned by Constantine’s mother, Helena. It is said that the palace was built on soil Helena brought back from Jerusalem.

Constantine had the church’s basilica built to house a collection of relics brought back from the Holy Land by his mother, specifically relics relating to the True Cross itself. Highlights of this gruesome Christian artifact collection include three supposed pieces of the Cross—a nail, a segment of the elogium (or inscription; in this case the famous INRI “Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudeorum”) inscribed upon a board said to come from the Cross, and two thorns alleged to come from the Crown of Thorns. They are all currently housed in the Chapel of Relics, designed by Florestano di Fausto.

If you happen to be a woman, and wish to see these holy objects, you will have to be patient. Women are only allowed inside once a year.

8Capela Dos Ossos

Evora, Portugal

Next to the Church of St. Francis in the Portuguese town of Evora is a small chapel called Capela dos Ossos. Like several entries on our list, it’s decorated with bones. Uniquely, not only is the interior of the chapel entirely covered with skulls and bones, but if you enter this small building and look up, you will find the remains of two full corpses, a women and a young boy staring back down at you, hanging from chains. It is said that they were the victims of a curse, who took shelter in the chapel. A welcoming sign at the entrance reads, “Nos ossos que aqui estamos, pelos vossos esperamos” (“We bones that are here, for your bones we wait”).

This 16th-century chapel houses the remains of about 5,000 monks, mostly exhumed from nearby cemeteries that had become overcrowded. There are several reasons why churches of the period decorated their walls in such a grisly fashion. One was practical—cemeteries were commonly overcrowded, and there were so few places to store the dead. The second was religious and social. Bones could be put to good use as a warning to the living to prepare one’s soul for death.

7Church Of Santo Stefano Rotondo

Rome, Italy

On the outskirts of Rome, away from the main thoroughfare of tourists, sits a church called The Basilica di Santo Stefano Rotondo al Monte Celio (Basilica of St. Stephen in the Round on the Celian Hill), or simply, the Santo Stefano Rotondo. It was consecrated by Pope Simplicius between 468 and 483 and is dedicated to Saint Stephen. Built on top of an old Roman site of Mithras-worship (known as a mithraeum), it’s a simply constructed church compared to others on this list, really only notable for being the first Roman church to be built with a circular plan, but it houses a unique collection of paintings.

Circling the inner walls are 34 paintings, each describing the death of a Christian martyr. Every one of them is hellishly violent, depicting in near-pornographic detail the tortures inflicted upon the martyrs, all in a perfectly naturalistic and life-like style. The paintings were commissioned by Pope Gregory XIII at the end of the 16th century.

No less a writer than Charles Dickens had this to say about the gruesome collection:

” . . . Such a panorama of horror and butchery no man could imagine in his sleep, though he were to eat a whole pig raw, for supper. Grey-bearded men being boiled, fried, grilled, crimped, singed, eaten by wild beasts, worried by dogs, buried alive, torn asunder by horses, chopped up small with hatchets: women having their breasts torn with iron pinchers, their tongues cut out, their ears screwed off, their jaws broken, their bodies stretched upon the rack, or skinned upon the stake, or crackled up and melted in the fire: these are among the mildest subjects.”

6Aghia Moni Convent

Nafplio, Greece

The Monastery of Aghia Moni is a beautiful, if little-known, complex just outside of Areia near Nafplio in Greece. It currently serves as a Greek Orthodox women’s retreat under the auspices of the Bishopric of Argolis.

Aghia Moni is famous for the spring that is located on its grounds, one with seriously pagan connotations. Sources are cagey about it, but most will admit that the monastery was dedicated to Zoodochos Pigi (the spring or source of life). The spring itself is associated with Kanathos, a legendary spring from Greek mythology.

The Greek traveler Pausanias, in his “Description of Greece,” wrote that “In Nauplia [in Argolis] . . . is a spring called Kanathos. Here . . . Hera bathes every year and recovers her maidenhood. This is one of the sayings told as a holy secret at the Mysteries which they celebrate in honor of Hera.”

Hera was the Greek queen of the Olympian Gods, associated with the sky and heavens, women, and marriage. Pausanias is implying that the Hera cultists performed rituals (called “Mysteries”) at the spring that were associated with this legend, and it isn’t hard to guess the aim of these rituals. That isn’t really the kind of thing Christian Orthodoxy likes to promote, so the spring has fallen into relative obscurity.

5The Barberini Coats Of Arms, St. Peter’s Cathedral

Vatican City

At St. Peter’s Cathedral in Vatican City is the Baldachin Altar along with its sculpted bronze canopy known as the Baldachin, both of which were sculpted by Gianlorenzo Bernini between 1624 and 1633 under the direction of Pius VIII. One notable feature about the alter is four plinths (columns), decorated with the Barberini family’s coat of arms—three bees arranged in a triangle on a blue field resting on an sculptured shield, with a woman’s head above it.

A close look reveals that each coat-of-arms, arranged two-to-a-column to make up a series of eight, is slightly different from the one preceding it. Some people believe that the series represents childbirth (the position of the woman’s head and the overall shapes and elements certainly look suggestive). Furthermore, take a look at the woman’s expression throughout the series; she goes from happy to obviously distressed and back. Furthermore, the shield bulges throughout the series until near the end; the woman’s face is replaced with that of a cherub or angel. What is this doing in the middle of a church?

One popular story has it that the sculpture depicts a promise that Urban VIII made to his niece, Giulia Barberini, to build an altar in her honor if her labor was successful. Others contend that it symbolically depicts the earthly struggles of the church in the past until it was “delivered” by the pope, who took great pains to place symbols of his power and family throughout the Vatican.

4The Sheela-Na-Gig Of Kilpeck

Herefordshire, England

Kilpeck Church (The Church of St. Mary and St. David) is located in Herefordshire, England near the Welsh border. It’s a simple, Norman-style, two-cell church built atop an older structure with dozens of elaborate and often-grotesque carvings, many of which are heavily influenced by Celtic styles. It’s famous for its sexually charged corbel (a weight support for buildings that were commonly sculpted), known as the Sheela-na-gig.

Sheela-na-gigs have been found on structures all over England, Ireland, and France. They depict a squatting woman, possibly associated with “old women” or hags, displaying their grossly exaggerated genitalia for all to see. They are usually depicted in a grotesque or comical manner, and the one at Kilpeck could be said to display both. It’s a very old sculpture, dating to at least the 12th century, and possibly belonged to an earlier chapel that once stood on the site.

Popular theories have it that Sheela-na-gigs are a pagan remnant, perhaps associated with various goddess traditions, but when placed in proper context with other carvings found around them, the theory holds little water. They fit in nicely with other Christian motifs common to the region of the time and probably served as Romanesque-era warnings about the dangers of sexual sins. The earliest known figures date to the 11th or 12th century and are usually found on Roman churches. They probably had a Continental origin. Another theory holds that they were created as wards against evil, and there is some evidence for this belief. Corbels have been found above doors or gates out of immediate eyesight, where they could have stood guard as talismans.

As the symbolic significance of Sheela-na-gigs began to wane, they moved from churches to buildings such as castles and gateways. Toward the end of their use, they even showed up as carvings on flintlock pistols of the baroque era.

There are male variations of Sheela-na-gigs, some of which may have been present at Kilpeck Church. Several corbels have been removed there, supposedly by an unnamed Victorian lady who was offended by what they depicted. Whatever the case may be, corbels depicting the male member are relatively common, and they too serve as a warning about the insidious consequences of lust.

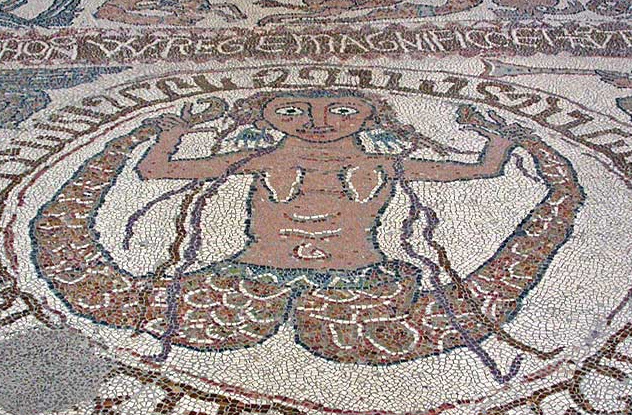

3Otranto Cathedral, Tree of Life Mosaic

Otranto, Italy

Consecrated in 1088, Italy’s Otranto Cathedral is on this list twice. The first reason is its floor, which is entirely covered by an amazing work of art called the Tree of Life Mosaic. It was commissioned in 1163 by archbishop Gionata d’Otranto and overseen by a monk named Pantaleone with labor provided by local and Norman craftsman and artisans from Tuscany. It was restored in 1993.

Every square foot of the church’s floor is covered by a mysterious mosaic that depicts a tree in a style similar to a genealogy illustration. Seen from above, the tree grows into every room of the cathedral, and the effect of the explosion of mythological and religious concepts all depicted together is mind-blowing.

What makes this mysterious work of art so intriguing is the variety of imagery and inscriptions that have no place in a Christian church. Images of the Greek goddesses Diana, Deucalion, and Pyrrha (the main figures in the Greek legend of a great flood) collide with images from Frazer’s Golden Bough, a depiction of King Arthur, and zodiac figures, to name only a few. All this is mixed alongside images of Adam and Eve, apocalyptic imagery and creatures, Cain and Abel, and other Christian concepts, but the whole thing is surprisingly free of any specific Christian symbolism. It even mixes in Islamic lore, such as bits of text in Arabic.

The Tree of Life Mosaic demonstrates that its creators were far more educated than the norm for cultures of its time. However they obtained their knowledge, the creators seem to have wanted to record all they knew of the world in one place.

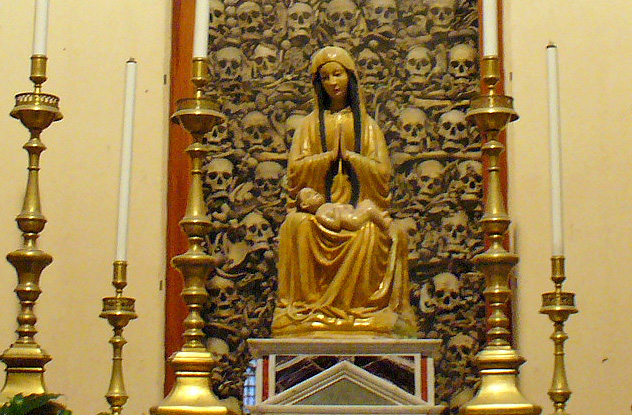

2Otranto Cathedral, The Skull Cathedral

Otranto, Italy

The second reason that Otranto Cathedral makes the list is the skulls. Just off of the main altar is a chapel, and the walls therein house the remains of 800 Christian martyrs. Some of the remains were also moved to the Church of Santa Caterina in Formello at Naples. The walls are neatly lined with the skulls of these martyrs behind glass.

Turkish Sultan Mehmet II had already conquered Constantinople, and 27 years later, he began a plan to take Rome itself by establishing a beachhead on the Italian coast at the port town of Brindisi. Along the way, he changed his mind and decided to strike at Otranto instead . . . a decision that changed everything.

When the invasion hit and the siege began, 350 members of Otranto’s garrison fled, leaving only 50 soldiers to hold back the invaders. The remaining townspeople helped against the siege as best they could.

On August 14, 1480, after a two-week siege, the Ottomans broke through and began raping and pillaging and gathered the women and children to be sold into slavery. They then marched around 800 male inhabitants of the town to a place called the Hill of the Minerva (afterward called the Hill of the Martyrs) and gave them a choice: convert to Islam or be beheaded. The men chose death.

Antonio Primaldi (or Pezzulla) was chosen to be the spokesman for the town, and he was the first man to be beheaded. According to Saverio de Marco in his Compendiosa istoria degli ottocento martiri otrantini (The Brief History of the 800 Martyrs of Otranto), when the sword fell, his lifeless, headless body stood up and refused to be moved. An executioner was so awestruck, he converted to Christianity right on the spot and was immediately executed. Yet, despite this miracle the beheadings continued.

The sacrifice of the townspeople of Otranto gave Ferdinand I, king of Naples, the time he needed to eventually repel the Ottoman advance. If not for them, all of Italy and Rome itself could have fallen to Islam. This is why their skulls are displayed and memorialized today, and why, in May 2013, Antonio Primaldi was canonized by Pope Francis as a saint along with all the rest of the Otranto martyrs. The occasion was the largest canonization of saints of all time.

1Sedlec Ossuary

Kutna Hora, Czech Republic

Compared to the Sedlec Ossuary, other churches that house human remains are nothing more than a Disney park. The remains of no fewer than 40,000 skeletons are preserved here.

The Seclec Ossuary is a small chapel located in the suburbs of Kutna Hora, just outside Prague. In 1870, woodcarver Frantisek Rint was appointed to do something about all the bones interred there. The church and its cemetery had become overcrowded over the centuries, thanks both to the church’s good reputation (and the alleged presence of soil from Golgotha, marking it as a holy site) and plague. Rint’s approach resulted in one of the most unique churches in history.

Bones are everywhere within the church. One of the most impressive displays is the Coat of Arms of the Schwarzenberg family, and the famous chandelier of bones contains at least one of every human bone within it.

Interspaced within the vast display of skulls, ribcages, leg and arm bones, and every other kind of bone are intricate carvings of angels and cherubs. There are candleholders made of bones, and entire walls are lined in skulls. Rint even signed his name in a display of bones.

Words don’t really do it justice. This gallery of photos helps give a proper sense of the church.

Lance LeClaire is a freelance artist and writer. He writes on subjects ranging from science and skepticism, atheism, and religious history and issues, to unexplained mysteries and historical oddities. You can look him up on Facebook, or keep an eye for his articles on Listverse.