Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

10 Pseudoscientists And Their Bizarre Theories

Science is something of . . . well . . . an inexact science. Throughout history, there have been countless explanations of natural phenomena that we’ve considered true, only to discover decades later that we were really off the mark. There are some scientists, though, whose theories seem so far out in left field that they’re not even playing the same game.

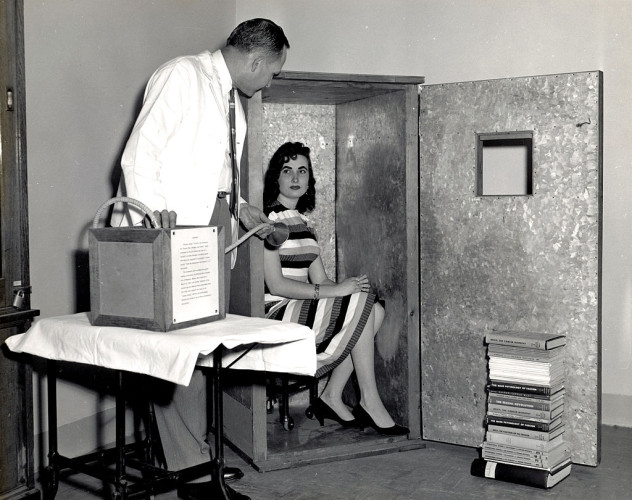

10 Wilhelm Reich

Orgone

Born in 1897, Wilhelm Reich was a psychiatrist enamored of the works of Sigmund Freud. He briefly worked with Freud and later started his own practice in 1922. By 1940, he had moved to the United States and fully developed his theories.

According to Reich, he had scientifically proven the existence of a compound that he described as a form of energy in the body that was the physical manifestation of the libido, building up in the body until it was successfully discharged through an orgasm. Reich built a machine that would allow him to study this energy, crossing the threshold between not only psychology and biology, but also between Eastern ideas and Western methods. He named the energy “orgone,” as he had first discovered it while researching the mechanics of the orgasm, but he soon was looking at orgone in areas outside of human biology. It formed a crucial part in his theories about everything from gravity to the weather.

Reich and his supporters have done a massive amount of research and experimentation on the properties of orgone. In 1947, he wrote a book called The Cancer Biopathy based on his experiments injecting cancerous cells in mice with what he called “bions,” or the most basic element of the energy of life. According to Reich’s theories, cancer was largely the result of the breakdown of these elements, and he claimed to have been able to extend the lives of his mice by weeks—and even longer when he used the energy collected from his orgone accumulator.

Today, there are still organizations (like the American College of Orgonomy) that formally study Reich’s work and offer Medical Orgone Therapy as an option for the treatment of disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, anorexia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

9 Frederic Petit

Another Moon

According to astronomer Frederic Petit, Earth has a second moon. Working in 1846 from an observatory in Toulouse, France, Petit claimed that the presence of the second moon explained away all the astronomical irregularities that other astronomers were having difficulty with. He claimed this second moon had an orbital time of only 2 hours, 44 minutes, and 59 seconds. At its farthest point from Earth, Petit’s second moon was about 3,570 kilometers (2,218 mi) away.

No one took his findings seriously when he made them public, but he continued to release new findings about his moon and its effects on the real Moon and the Earth for 15 years after his initial discovery. Petit’s theory might have gone completely unnoticed by the scientific community if it hadn’t been picked up by Jules Verne in From the Earth to the Moon.

The reference is a brief one, but Verne comments about this second moon and names Petit as the man who discovered it. Instead of fading into scientific obscurity, amateur astronomers started searching the skies for evidence of this second moon, which has caused many other discoveries about the celestial bodies in the Earth’s orbit. In 1989, a man named Georg Waltemath claimed to have discovered that the planet was orbited by not only a couple of moons, but a whole network of mini moons. Some of these moons illuminated the sky with the same strength as the Sun, he claimed. Waltemath also released a series of dates and times at which people would supposedly be able to see these mini moons passing in front of the Sun. A lot of people spent several days in February 1898 staring at the Sun, but no one saw anything out of the ordinary.

8 Marcel Vogel

Plants With Feelings And Quartz Storage

Marcel Vogel began his life’s research after discovering that plants have feelings, too. Sort of. A technician for IBM, Vogel researched plant responses to stimuli—cutting, tearing, and damaging the plants that elicited a response that could be read and understood in terms of released energy. According to Vogel, he discovered that the plants were responding but only in conjunction with his own emotions and energy. He determined that they were storing his mental energies and releasing them at the moment he interacted with them.

That was in the 1960s. In 1974, Vogel was introduced to quartz crystals and spent the rest of the 1970s investigating their tendency to also act as a vessel for storing, magnifying, and converting mental energies. In 1984, he founded Psychic Research, Inc., with some pretty lofty goals. He wanted to purify water by rearranging its energy and speed up the aging process of wines by the same methods.

Originally unimpressed with the idea of crystals, Vogel’s mind was changed after he claimed to have meditated on the face of the Virgin Mary while focusing on a crystal. After an hour of focus, the crystal in question had clearly taken on the shape of his mental image.

From there, he developed a particular cut of crystal that was supposed to make focusing energies easier. The Vogel-cut crystals—which are still available for a pretty hefty sum—are advertised as having no energy themselves. Instead, they amplify the energies given off by a person’s body. Vogel reported that the most powerful force is love, and that his crystals are capable of capturing, storing, magnifying love.

7 Ignatz Von Peczely

Iridology

The human eye has long been considered a window into the soul. For centuries, medical professionals have studied their patients’ eyes to assess their wellbeing. While our eyes can certainly reflect our health—or lack thereof—Hungarian doctor Ignatz von Peczely took the idea to a new level.

It began when he reportedly noticed a black mark in the eye of an owl whose leg he’d broken. Although the incident happened when he was young, it stayed with him throughout his medical training at Vienna Medical College. By the time he graduated in 1867, he had studied the eyes of countless patients and created a chart of what part of the iris was related to what part of the body.

According to von Peczely and a contemporary named Nils Liljequist, any disorder in the body could be diagnosed by looking for changes in the color of the iris. They firmly believed that it was absolutely unnecessary to conduct a physical examination of a patient. Instead, looking at the portion of the iris that corresponded with the body part in question would reveal exactly what was wrong.

Today, there are still guilds of practicing iridologists who are trained to detect illness and genetic flaws through the eyes. People are sorted into three “constitutional types” that are defined by eye color. Blue-eyed people belong to the Lymphatic Constitutional Type, and are predisposed to skin problems like acne, dandruff, arthritis, bronchitis, and eye irritations. Brown-eyed people are defined as belonging to the Hematogenic Constitutional Type, and they’re prone to developing anemia, diseases of the digestive system, chronic and degenerative illnesses, diabetes, and gas. The third constitutional type is a mix of the two, called Biliary Constitutional Type. If your eye color is a mix of brown and blue, that means you’re susceptible to the illnesses associated with both types, and specifically gas and diseases of the blood.

6 Judge Edward Jones

Personology

According to a book written by the founder of the International Centre for Personology, the science started in the 1930s with a judge in the Los Angeles court system. After seeing defendant after defendant, Judge Edward Jones began correlating the facial appearances of those who found themselves in his court with the crimes that they committed.

After the judge laid the groundwork for this so-called science, more research was done by a newspaper editor named Robert Whiteside. According to his findings, a person’s face could be a clear indicator of what kind of personality they had; both were genetically determined, it was stated, so therefore they must be connected.

We’ve talked about the early theories of criminology and how it was proposed that a person’s tendency toward a criminal lifestyle was written pretty clearly on his physical form. Personology is a similar idea. There are still institutes that teach people how to read into the structure of faces and bodies, claiming to increase your customer service skills, interpersonal relationships, and teaching skills.

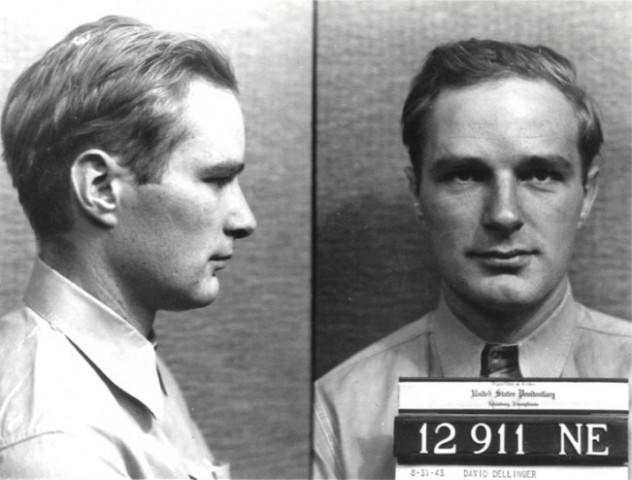

5 Alfred William Lawson

Lawsonomy

Cy Q. Faunce was a pseudonym taken by a man named Alfred William Lawson and used to spread the word about how wonderful and brilliant Lawson thought he was without raising any suspicion. One of Faunce’s writings claims that, “The birth of Lawson was the most momentous occurrence since the birth of mankind.”

Lawson spent 20 years as a professional baseball pitcher. When he grew tired of that profession, he turned to aviation with mixed success. He’s credited with coming up with the idea for an airliner, but his own attempts to form a company—and build a fleet of airliners—failed miserably.

He then founded the University of Lawsonomy, where his “knowlegians” would teach only one thing: the science of Lawsonomy. All other books and studies were absolutely banned.

So, what were the teachings and beliefs of Lawsonomy? There is no such thing as energy, just a constant push-pull battle between things with high density and low density. Earth is actually made of something called “lesether,” and it’s swimming in ether. Because of the difference in densities between the Earth and the material it’s surrounded by, everything that exists on Earth is sucked into the planet through a big hole near the North Pole and distributed around the globe through its internal arteries. It’s the same way humans work, too. When this process of pressure and suction stops, so does life.

While we’re alive, we’re at the mercy of the Menorgs and the Disorgs that live in our brains. These tiny creatures run around in our heads, the former organizing things and making sure everything’s all neat and tidy, the latter creating chaos, havoc, and quite a bit of mess.

Food and nutrition are complicated concepts in Lawsonomy. Plants are the Earth’s parasites, and it’s likely that they’re communicating with each other in a way we can’t understand. When early mankind lived on plants, we were a healthy, robust species. We became weaker and more prone to disease when we started cooking our food, as cooking sucks all the life and nutrients out of food. Lawson came to this conclusion because of what happens to a person when thrown onto a fire. It stands to reason that the same thing happens to everything else that lives.

The University of Lawsonomy came to an end after an investigation by the Senate Small Business Committee, who began inquiry by questioning what the non-profit university was doing with its funds and ended the inquiry by questioning literally everything about Lawsonomy.

4 Hanns Horbiger

Cosmic Ice Theory

In the 1920s, Austrian Hanns Horbiger added a new theory to the scientific world, and people around the globe loved it. Its popularity was in no small part due to the fact that it didn’t have much in the way of scientific jargon tacked to it, and it was extremely easy for the everyman to understand.

Simply put, everything was made of ice.

Ice was the material of everything in the universe, from the stars in the sky, to the Earth, to the development of life on it. Horbiger touted the theory as a revolutionary one that provided that singular string needed to tie everything in the known universe together with a neat little bow, and that was an attractive idea.

His explanation for the development of his theory was pretty ambitious. Horbiger experienced a vision in 1894. It was revealed to him that ice was the basis of everything. The facts that he was building his theories around were based on, as he put it, “creative intuition” and “artificial experiments.” Rather than starting with the scientific community, Horbiger introduced his theories to the public first, hoping that popular opinion would be able to sway the scientific community to back him. Surprisingly, it kind of worked.

Hot on the heels of the penning of cosmic ice novels, books, and radio programs was the adoption of the Cosmic Ice Theory by the National Socialists in Germany. Research in the field became one of the personal pet projects of Heinrich Himmler, even though more mainstream German scientists were still wholeheartedly denying that it had any merit whatsoever. After the war, Himmler’s support of the project helped put the final nails in its coffin—it was condemned as just another bit of pseudoscience and propaganda.

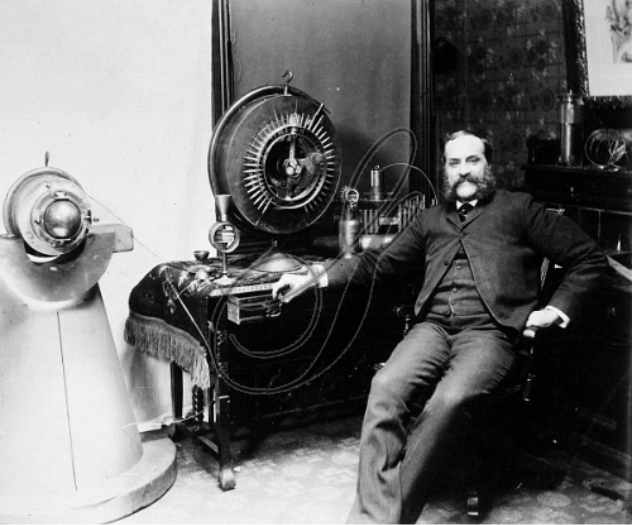

3 John Keely

Perpetual Motion Engine

The idea of a perpetual motion machine is intriguing. People have been trying to make such a device since the Middle Ages. The generally accepted definition of the perpetual motion machine is one that produces an amount of power greater than the fuel it consumes—which is, of course, impossible.

That didn’t stop John Keely from saying that he’d made one.

Born in 1837, Keely held a handful of different jobs—painter, carnival barker, theatrical orchestra member—before he went public with the announcement that he had discovered a completely new form of physical energy that could produce an amazing amount of power. Using the energy of water molecules, Keely could sync the molecular vibrations with his machine and create endless power.

It seems pretty preposterous, but Keely was convincing. He soon had investors and $5 million in capital to start Keely Motor Company. He was able to demonstrate his full-scale engine in 1874. His descriptions included a lot of words like “ether-etheric” and “metallic impulses,” and turning the machine on was often done with the aid of the vibrations of a musical instrument. He kept investors interested with the help of a few cheerleaders, but at the same time he refused to apply for any patents for fear that someone would steal his idea.

His company went public in 1890, and it was then that organizations like Scientific American began to blow some pretty big holes in his theory. He kept the company—and the money—going for another eight years until he died in 1898. By then, the Keely Motor Company had been in business for 25 years without a product and without paying a single investor a single dividend. When investors checked out his mysterious, off-limits lab, they found his engine, a false floor, and a container of compressed air that would give the illusion of power, just like researchers from Scientific American had predicted.

2 Rene Blondlot

N-Rays

In 1903, the scientific community was still all sorts of excited about the concepts of radiation and X-rays. French scientist Rene Blondlot was experimenting with X-rays when he claimed to have stumbled on something incredible: more waves. He called them N-rays after his town, Nancy, and his experiments were met with a combination of overwhelming excitement and skepticism. The skepticism was due in part to the fact that the N-ray theory had one of the biggest hallmarks of pseudoscience—an inability to easily repeat results.

Blondlot first detected his mysterious N-rays when he saw a small spark out of the corner of his eye. His instructions on how to detect N-rays were pretty questionable. They included locking oneself in a dark room for a while before conducting the experiments to make sure the eyes were appropriately adjusted. He also noted that while some people would be able to see them right away, others would have to try again and again . . . and maybe once more.

Still, Blondlot and his fellow French scientists came up with a list of the properties of N-rays, partially spurred by the fact that German competition had discovered X-rays. N-rays could reportedly pass through anything that would block light and would be stopped by transparent materials. They were given off by the Sun, but only on cloudy days. Another French scientist, Augustin Charpentier, backed Blondlot and took the theory farther by saying that he’d proven that the human body also gives off N-rays. So in tune were we with N-rays that repeated exposure had a supercharging effect on our senses.

If only.

Researchers in England and Germany couldn’t see what all the fuss was about, so a physicist from Johns Hopkins University went to Blondlot to find the truth once and for all. With a bit of sleight of hand, the American physicist was able to prove quite quickly that it was all absolute nonsense. A year after Blondlot’s groundbreaking discovery, he was ruined.

1 Albert Abrams

Radionics

In the early 1900s, a doctor named Albert Abrams claimed to have discovered the secret to diagnosing and curing almost any ailment of the human body. He claimed that the answer was in the vibrations that came from each cell. These vibrations, which he called the Electrical Reactions of Abrams, could be read by examining something associated with the patient and then adjusted through the use of one of his many, many devices.

The practice was called radionics, and those that practiced it proclaimed they could diagnose the patient by looking at a bodily sample—blood, saliva, fingernail clipping—or even by examining a personal effect belonging to the afflicted. Some used dowsing rods and mysterious, electronic black boxes in their diagnosis, but some practitioners deemed sensitive enough to the vibrations could read tissues and items without the help of devices.

Not surprisingly, there were quite a lot of people who called the science fraudulent. Scientific American got involved with this, too, along with the United States Food and Drug Administration. The FDA sent a couple blood samples for radionic studies to investigate whether the results were at all accurate. The first sample was diagnosed with colitis, although the person it was taken from was actually dead. An amputee was diagnosed as having arthritis in the leg he’d lost, and a chicken was diagnosed with a sinus infection.

Amazingly, there are still organizations that practice radionics, which they describe as an intuitive science used to diagnose problems with a person’s energy fields.

+ Franz Mesmer

Animal Magnetism

If you guessed that Franz Mesmser is where we get the word “mesmerism,” you’d be correct. But there was much, much more to his theories than just hypnosis, and they were popular enough to last for decades.

Mesmer’s theories got off to a hairy start when he wrote his dissertation on the impact of the movement of the planets on the human body in 1766. We say wrote, but we really mean he lifted it almost completely from an earlier work by a well-known English physician. At any rate, he later credited the earlier work, but his career path was already set.

After marrying a wealthy widow and opening his own practice, he was introduced to a new method of treating patients who rejected conventional treatments. When he was rewarded with success in curing a woman with the application of magnets, he continued experimenting with what he called “animal magnetism.”

His contemporaries viewed the practice with quite a bit of skepticism, even when he claimed to have restored sight to a woman who had been blind since the age of three. His appearances in front of the Royal Academy of Sciences didn’t go well, and he was equally frowned upon by the Royal Society of Medicine. The laypeople, though, couldn’t get enough of it. Spurred by the support of people he cured, animal magnetism finally gained the attention of various European governments.

Further experimentation determined that there was little difference between the actual effects of magnetism administered to the human body and the mere suggestion of the presence of magnets. While some continued to believe in the good doctor after the release of the official scientific findings on Mesmer’s work, it largely died off as a serious practice.