Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

10 Original Thinkers Persecuted As Heretics

Jesus taught that no one should be persecuted for having an opinion different from his. But his early followers don’t seem to have gotten the memo, because medieval priests had a rather different attitude toward people who thought for themselves.

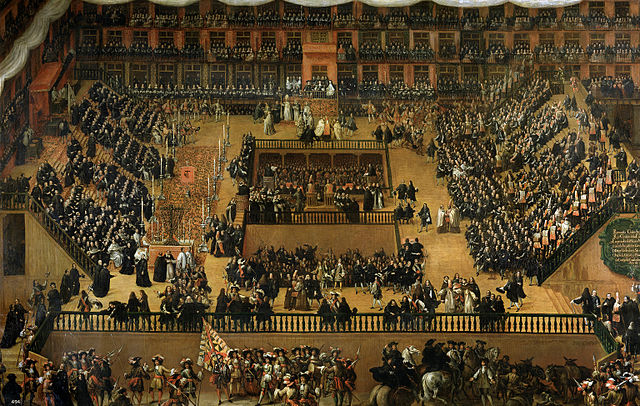

By the second century, allowing differences of opinion on religious matters was perceived as inherently dangerous, but it wasn’t until 352, at the First Council of Nicaea, that an official orthodoxy was firmly established. Twenty-eight years later, the Emperor Theodosius issued an edict giving Christian leaders the legal clout to officially treat heresy as a crime. They expanded those powers right up until the Enlightenment.

10Pietro D’Abano

Pietro d’Abano was an Italian philosopher, doctor, writer, and astrologer (and possibly an alchemist), who eventually came under suspicion of being a sorcerer. A grimoire entitled The Heptameron was attributed to him, although he probably wasn’t the author.

After his early education in Padua, d’Abano journeyed to Constantinople, where he studied Greek until around 1290. By 1300, he was in Paris, where he earned doctorates in philosophy and medicine. He also made the acquaintance of a number of powerful men, which would eventually partially save him.

Whether due to his wealth or his belief in astrology, rumors of black magic formed around d’Abano. Specifically, it was said that “any money he paid out would be magically paid back to him.” Such stories attracted the attention of the Dominican monastery of Saint-Jacques in Paris, which brought charges of witchcraft and heresy against him. An attempt at relocation failed and he was twice charged by the Inquisition.

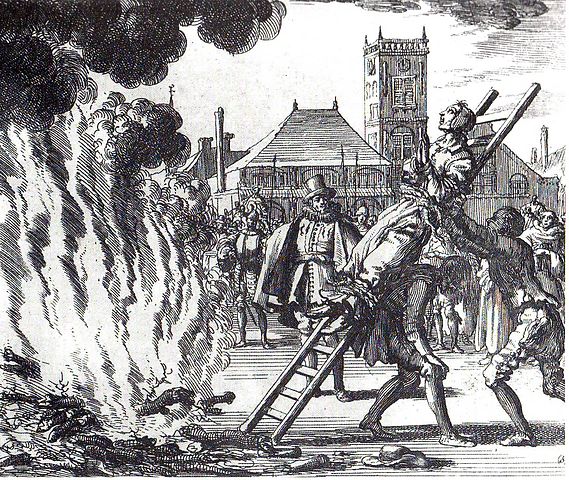

Acquitted on the first charge, he was prosecuted a second time on charges of “denying the existence and influence of spirits and demons.” He died in prison while awaiting his verdict. The Inquisition was denied the chance to burn his body, as his friends snuck it out of prison and buried it.

Not to be snubbed, the Inquisition simply burned him in effigy. Apparently, that wasn’t enough— his books were put on trial again 40 years later. Found guilty, his body was exhumed and burned.

9Cecco d’Ascoli

Cecco d’Ascoli was an Italian poet, physician, and professor of mathematics and astrology at the University of Bologna from 1322–1324. He is best known today for his encyclopedic poem l’Acerba.

At some point, d’Ascoli probably entered the service of Pope John XXII, where he cultivated a friendship with the great poet Dante (who he supposedly then argued with at every turn). His first offense against the Church came when he wrote a commentary on the work of John de Sacrobosco in which he expounded on a number of unusual theories concerning the employment of demons. As a result, he was given a fine of 70 crowns and ordered to seek penance through prayer and fasting.

To escape his sentence, d’Ascoli moved to Florence in 1324. This was a poor move, since he had made many enemies there with his attacks on the Florentine poets Dante and Guido Cavalcanti, and the physician Dino di Garbo soon resurrected the charges of heresy against him. Once again he was found guilty. In 1327, at the age of 70, he was burned at the stake in Florence.

8Meister Eckhart

Johannes Eckhart, commonly known as Meister Eckhart, was a German mystic, theologian, and philosopher who taught at Dominican schools in Paris, Strasbourg, and Cologne. His writings dealt with humanity’s nearness to God and inspired a 14th-century mystical movement within the Dominicans.

His willingness to work with the common people was deemed suspicious by conservative elements in the Church, and he was eventually falsely accused of a connection to the Beghards (a religious order which taught that those who achieve perfection are unable to sin).

He was first brought before the Inquisition in 1326 by the Franciscan Archbishop of Cologne, Henry of Virneburg. Aware that Henry considered him an enemy, Eckhart insisted on being judged by the Pope, walking around 800 kilometers (500 mi) to Avignon. He died in prison there in 1327, before his case could be settled.

History doesn’t tell us exactly how his death came about, but what we do know is that Pope John XXII issued a bull condemning 28 of Eckhart’s articles as heretical. In a fitting twist, Pope John was himself later condemned as a heretic.

7William Of Ockham

William of Ockham was an English Franciscan and one of the prominent philosophers of the High Middle Ages. While he never completed his training in theology at Oxford, he wrote a number of important works and is credited with formulating the principle known as “Occam’s Razor.” Although properly expressed as “don’t multiply entities beyond necessity” it can be more simply explained as “when you have two competing theories that make exactly the same predictions, the simpler one is the better.”

Some of Ockham’s writings denied the right of the papacy to interfere with the affairs of states, a belief that brought him into conflict with the Church. In 1323, he was hauled up before a Franciscan meeting in Bristol and made to defend his views. Around the same time, persons unknown went to the Papal court at Avignon and charged him with heresy.

In 1324, Ockham was brought to Avignon to defend the charges, although he was not placed under arrest or officially condemned. There, he became caught up in the conflict between Pope John XXII and his fellow Franciscans. The Franciscans believed that Jesus and his disciples did not own property, and sought to emulate them by living lives of humble poverty. The Pope had rejected these views, leading the Franciscans to ask Ockham to review the matter. Ockham concluded that the Pope’s views on the matter were heretical—and to make matters worse, he had continued to hold them even after being shown that they were heretical. In other words, the Pope himself was a heretic.

Now fearing for his life, Ockham was forced to flee Avignon on May 26, 1328. He eventually fell under the protection of the Holy Roman Emperor, who was in the middle of a political dispute with Pope John. For leaving Avignon without permission, Ockham was officially excommunicated. He spent the rest of his life under Imperial protection.

6Jan Hus

Jan Hus was a Czech priest and a precursor figure to the Protestant Reformation. Born at Husinetz in southern Bohemia, he studied at the University of Prague. Ordained a priest in 1400, he was appointed rector of the university from 1402–1403.

His troubles began due to his support of the English reformer John Wycliffe. The Church had condemned many of Wycliffe’s beliefs, but Hus translated his Trialogus anyway. Drawn to Wycliffe’s contention that a sinful authority ceases to be an authority, he began to speak out against the morals of contemporary religious leaders. This earned him the hatred of the Archbishop of Prague, but he had the support of Holy Roman Emperor Wenceslaus IV, as well as the common people of Bohemia.

But a changing political landscape eventually gave the Archbishop the upper hand. He forbade Hus from preaching and ordered that his books be burned. Hus was excommunicated by Pope John XXIII shortly afterward. This didn’t stop him—instead, he retired to a castle near Tabor where he continued to write, arguing that a morally compromised Church was no longer infallible.

In 1414, the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund invited Hus to appear before the Council of Constance to justify his views, promising him safe conduct if he did so. Hus agreed, but once he had arrived the council refused to recognize the agreement. Hus was quickly imprisoned and tried for heresy, along with his friend Jerome of Prague. In 1415, Hus was burned at the stake, still refusing to recant his beliefs unless someone could demonstrate how they were wrong.

5Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus was a 16th-century Spanish polymath and early Unitarian, well-versed in theology, mathematics, astrology, geography, and medicine. Impressively, his unorthodox views drew condemnation from both Catholics and Protestants.

Today, Servetus is best known to theologians for his thoughts on the Trinity, which he revised several times in an effort to gain acceptance. He asserted that the Word is the eternal expression of God, the Spirit the motion of God’s power flowing through mankind, and the Son the union between the Word and Jesus.

When some of his more controversial letters came into the Inquisition’s possession, he was seized and brought to trial at Lyon. Although he was found guilty, Servetus managed to escape, and so his body was burnt in effigy.

Unfortunately, Servetus had also drawn the ire of Protestants, leaving him few places to escape to. In 1553, he appeared in Geneva, where John Calvin himself was instrumental in his arrest and trial for heresy. He was found guilty of holding heretical views on the Trinity and baptism and was burned alive on October 27. His death resulted in widespread criticism of Calvin, sparking a debate among Protestants about the death penalty for heretics.

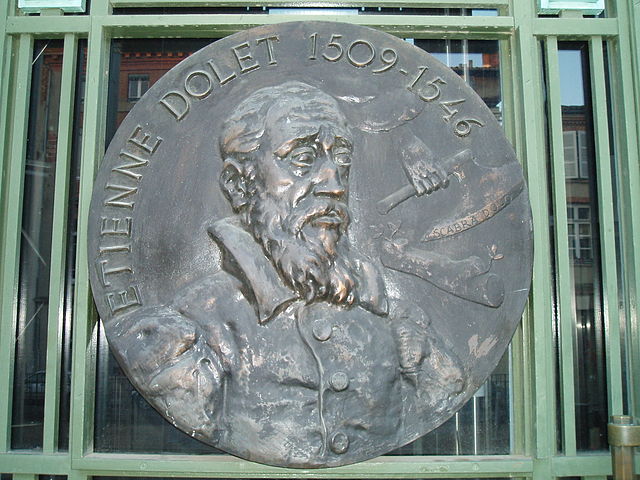

4Etienne Dolet

Commonly called “the first martyr of the Renaissance,” Etienne Dolet was a French humanist scholar known for his anti-Trinitarian views. He was possibly of royal rank—a doubtful tradition makes him the illegitimate son of Francis I.

After studying in Paris and Padua, he moved to Toulouse, where his argumentative nature and anticlerical temperament caused problems. Banished from the city, he ended up in Lyons, where he was imprisoned for murdering a painter. However, the act was deemed justifiable, and he eventually received a royal pardon.

After his release, Dolet became a printer. During this time, he faced numerous accusations of atheism and was imprisoned on three occasions: twice for publishing Calvinist works and once for publishing a dialogue by Plato which denied the soul’s immortality. In 1546, the theological faculty of the Sorbonne condemned him for heresy and he was tortured and burned at the stake in Paris.

Dolet was willing to publish a variety of religious opinions and advocated the reading of the Bible in the vernacular, activities that saw him condemned by Catholics and Protestants alike. It must be admitted that he had an uncanny ability to make enemies, but in the end it was his tendency to think for himself that proved intolerable to the authorities.

3Pomponio De Algerio

Pomponio De Algerio was a law student at the University of Padua when his ideas attracted the attention of the Inquisition. Brought before a tribunal, he wore his university cap and gown to remind his accusers that, as a student, he had the right to express his ideas. According to the transcripts of the trial, Pomponio declared that “no Christian should restrict himself to any particular church. This church deviates in many things from truth.”

During his imprisonment, Algerio refused an opportunity to recant, writing of the hope and serenity he found while locked away. After a year in prison, Algerio was extradited to Rome and handed over to the civil authorities for sentencing. When a monk from the Order of St. John the Beheaded offered him the “mercy” of being strangled, Algerio refused.

In 1556, the 25-year-old student was boiled in oil (although other accounts say that he was burned). The Venetian ambassador to Rome reported that he lived for 15 minutes, remaining calm and composed the entire time.

Many people ran afoul of the Inquisition within universities, where clandestine teachings were increasingly common. At Siena, Girolamo Borri was imprisoned for denying the immortality of the soul (although he was later allowed to resume teaching). In Padua, Cesare Cremonini had one of his books banned, while his colleague Fabio Nifo staged a daring escape after being arrested by the Inquisition.

2Lucilio Vanini

Lucilio Vanini was an Italian Renaissance freethinker who studied philosophy and theology at Rome and the physical sciences at Naples. He then moved to Padua, where he was ordained a priest and studied law. Influenced by the Alexandrists, Vanini is remembered for his eerily prescient belief that humans evolved from apes.

After obtaining the priesthood, Vanini roamed throughout France, Switzerland, and the Low Countries, teaching and spreading openly anti-Christian views. After a few run-ins with the authorities, he tried to evade suspicion by writing a book against atheists. However, he was almost certainly an atheist himself, and his second book, De Admirandis Naturae Reginae Deaeque Mortalium Arcanis expressly countered his original arguments, which were rather ironic to begin with.

His books were quickly condemned to the flames and Vanini was arrested in Toulouse in November 1618. After a prolonged trial, he was found guilty of atheism. His tongue was then torn out, before he was strangled at the stake and burned in February 1619.

1Kazimierz Lyszczynski

Kazimierz Lyszczynski (or Cazimir Liszinski) was a Polish nobleman, landowner, and philosopher, recognized today as possibly Poland’s first atheist. Sadly, none of his writings survive, as they were burned along with him.

Lyszczynski had read Henry Aldsted’s treatise Theologia Naturalis, writing “therefore God does not exist” in the margin of his copy (it’s actually possible that he was just making fun of the author’s arguments). Unfortunately for him, a debtor of Lyszczynski’s named Brzoska eventually came upon the note. Possibly sensing a way to get out of his debt, Brzoska took the book to Bishop Witwicki of Posnania. Together with Bishop Zaluski of Kiof, they denounced Lyszczynski as an atheist.

In 1639, Lyszczynski was brought up before the Diet, where Brzoska claimed that he had denied the existence of God and uttered blasphemies against the Virgin Mary. Terrified, Lyszczynski agreed to all the charges, offered up a recantation, and threw himself on the mercy of the court. Apparently, his accusers were scandalized that Lyszczynski was even allowed to defend himself. Although the king of Poland and Pope Innocent XI both condemned the trial, he was nonetheless found guilty and sentenced to death.

The following account, written by Bishop Zaluski, describes his sentence: “After recantation the culprit was conducted to the scaffold, where the executioner tore with a burning iron the tongue and the mouth, with which he had been cruel against God; after which his hands, the instruments of the abominable production, were burnt at a slow fire, the sacrilegious paper was thrown into the flames; finally himself, that monster of his century, this deicide was thrown into the expiatory flames; expiatory if such a crime may be atoned for.”

Even that might not have been enough—some versions say that Lyszczynski’s ashes were gathered together and shot from a cannon.

Lance LeClaire is a freelance artist and writer. He writes on subjects ranging from science and skepticism, atheism and religious history, to unexplained mysteries and historical oddities, among other subjects. You can look him up on Facebook, check out his new sometimes serious/sometimes satirical blog on atheism and religious issues at lleclaire.wordpress.com, or keep an eye for his articles on Listverse.