Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Our World

Our World 10 Ways Your Christmas Tree Is More Lit Than You Think

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Coolest Stars to Set Sail on The Love Boat

History

History 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the American National Anthem

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Facts About The Doge Meme

Our World

Our World 10 Ways Your Christmas Tree Is More Lit Than You Think

Movies and TV

Movies and TV The 10 Coolest Stars to Set Sail on The Love Boat

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us History

History 10 Things You Didn’t Know About the American National Anthem

Technology

Technology Top 10 Everyday Tech Buzzwords That Hide a Darker Past

Humans

Humans 10 Everyday Human Behaviors That Are Actually Survival Instincts

Animals

Animals 10 Animals That Humiliated and Harmed Historical Leaders

History

History 10 Most Influential Protests in Modern History

Creepy

Creepy 10 More Representations of Death from Myth, Legend, and Folktale

Technology

Technology 10 Scientific Breakthroughs of 2025 That’ll Change Everything

10 People Who Were The Last Of Their Kind

Nothing lasts forever. Throughout history, there have been many cultures and traditions that have vanished. Some of them died out naturally while others were devastated by warfare, disease, or the changing times. Sometimes an entire history can rest upon the shoulders of a single, solitary survivor. In this list, we look at 10 people who had (or have) the sad distinction of being the last of their kind.

10The Last Of The Shakers

The Shakers are a religious sect from England who arrived in the United States just prior to the American Revolution. An offshoot of the Quakers, the Shakers were so called because of their tendency to speak in tongues. They believed that both men and women were made in God’s image, making them one of the first religious movements in which women played a major role. The Shakers’ leader, Mother Ann Lee, considered herself a female counterpart to Jesus Christ.

Shaker communities flourished in the United States, and there were around 4,000 Shakers before the Civil War. They lived a communal life, dedicating themselves to craftsmanship, farming, and prayer. However, the rules of Shaker life demanded celibacy; Mother Ann viewed sex as a sin (since she had had four children die in childbirth), and thus Shaker membership was limited to new converts. Following the Civil War, the number of Shakers began to decline, and many Shaker villages were abandoned. As of 2010, there were only three Shakers still alive. They live in Sabbathday Shaker Village in Maine, where they still practice their traditional way of life and keep the door open for new converts.

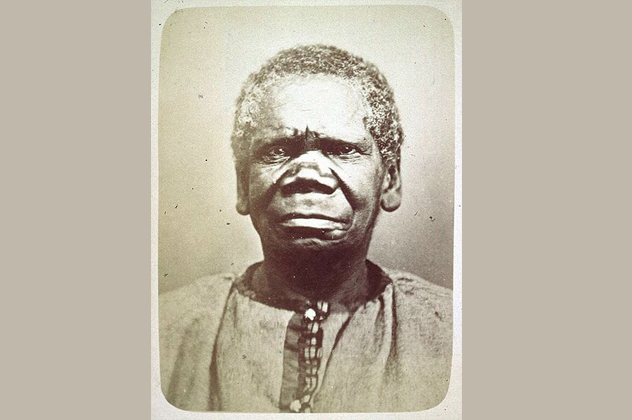

9Truganini, The Last Tasmanian

Truganini was the last full-blooded Aboriginal Tasmanian. Her people, who had inhabited the island of Tasmania for 45,000 years, were almost completely decimated by the Black War, a prolonged conflict between them and newly arrived European settlers. The settlers ravaged the Aborigines not only with weapons but also with disease, to the point where there were only around 200 Aborigines left alive.

Into the picture stepped a well-meaning English preacher named George Augustus Robinson, who thought he could protect the Tasmanians by resettling them on Flinders Island. He employed the teenage Truganini, the daughter of an Aboriginal chief whose husband had been murdered by settlers, to travel with him and help translate. But Robinson eventually gave up his quest and abandoned Truganini. With nowhere to turn, she and some fellow Tasmanians turned to a life of crime, robbing settlers to support themselves. She was eventually caught and sent to Flinders Island, which turned out to be more like a prison than a refuge. The population on Flinders Island died out, and eventually Truganini was the last one left alive.

8The Last Navajo At Wupatki

Wupatki National Monument in Arizona is a mesa with a rich history. The area has been inhabited intermittently for over 11,000 years by many different societies, including the Sinaguan people, who built a remarkable pueblo there approximately 800 years ago. More recently, the ancestors of the modern Hopi tribe settled in the area, followed by a Navajo tribe, a few of whom remain there today.

Most of the Navajo at Wupatki were forced off their land in 1864. That year, the US Army forcibly relocated many of those living in Arizona into New Mexico, an event known as the Long Walk. Eventually, some Navajo returned and resettled the mesa, but in 1924 the government declared the area a national monument.

Only the Navajo already living at Wupatki were allowed to stay. Stella Peshlakai Smith is one of those. She was born in Wupatki just one month before the area was closed off to new settlement. When she dies, her family will have to vacate her property, as they will not be allowed to live there. Unless the law changes, Stella Peshlakai Smith will be one of the last people to live on Wupatki.

7The Last Ninja

Jinichi Kawakami is a university professor, museum director, and engineer who also stakes a claim to being the last of Japan’s legendary ninjas. Kawakami started practicing ninjutsu when he was six years old, and eventually he rose up the ranks as the 21st head of the Ban ninja clan, which goes back 500 years. While this role gave him access to secret ninja teachings, he says that ninja techniques have no place in the modern world. Thus, he doesn’t plan to appoint a successor to take over the Ban clan after he’s gone.

Instead, to help preserve an ancient tradition, Kawakami has spent considerable time studying ninja history and techniques. He runs the Ninja Museum of Igaryu, which collects and preserves the secret ninja scrolls, including recipes for poisons—recipes which Kawakami says he can no longer use because he has no way of trying them out.

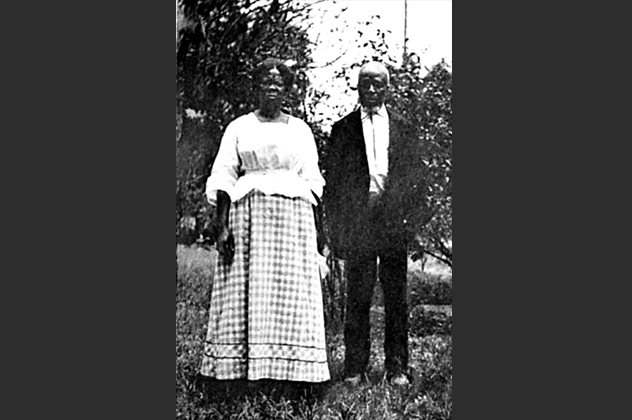

6Survivor Of The Last Slave Ship

Fifty years after the United States outlawed the international slave trade, many slaves were still smuggled into the country illegally. Cudjo Lewis was one of these slaves, a passenger on the last slave ship which set sail three years before emancipation. Born in what is now Benin, Africa, Cudjo was taken captive when a rival king attacked his town. Cudjo was sold into slavery and put aboard a ship called Clotida bound for Mobile, Alabama.

The 45-day journey was difficult, and its illegal nature made it dangerous for both the slaves and the crew. Cudjo later recounted to writer Zora Neale Hurston just how terrifying the experience was—the slaves were kept naked belowdecks in dark, cramped conditions while the Clotida sailed through a hurricane and avoided both pirates and the navy. Even when they arrived in Mobile, the slaves had to be hidden away until they could be divided up among various plantations.

Cudjo remained a slave for five years before gaining emancipation. He and the other survivors of the Clotida settled just outside of Mobile in a place they called African Town on land that was purchased from their former owners. Cudjo lived well into the 1930s, longer than any of the other citizens of African Town.

5Last Of The Awang Batil

Awang Batil is an ancient Malaysian oral storytelling and performance tradition. In Awang Batil, the storyteller performs his story while banging on a brass drum, or batil. Usually, the performance opens with the burning of incense to purify the storytelling area. The storyteller also uses a variety of masks and other props, like folded handkerchiefs, to embellish the stories, which themselves are often festive and filled with humor.

Once common around Malaysia, Awang Batil and similar oral traditions have been slowly disappearing—even in rural areas, where some traditions have managed to endure—as people turn to television and other modern forms of entertainment. Currently, there is only one living practitioner of Awang Batil: Romli Mahmud, who is in his fifties. Mahmud doesn’t intend to teach anyone else his art, as he thinks that the traditional tales are too old and too long to connect with modern audiences, and thus the tradition will likely die with him.

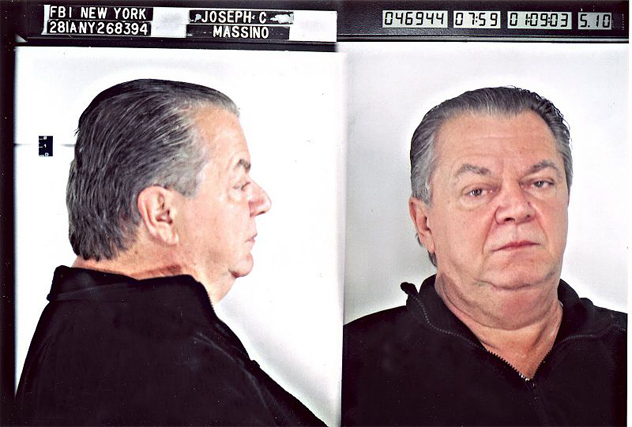

4The Last Don

By the early 2000s, New York’s feared “Five Families” of the Cosa Nostra were a shell of their former selves. John Gotti, the terrifying leader of the Gambino crime family, had died in prison. The bosses of the Genovese and Colombo crime families had been incarcerated. And Little Al D’Arco, of the Lucchese family, had turned against the Mafia to become a government witness.

The one holdout was Joseph Massino, boss of the Bonanno crime family, whom the media appropriately dubbed “The Last Don.” Massino had risen up the Bonanno ranks to lead the family following a bloody struggle for power between rival factions. It was during this time that Massino was suspected of having conspired to murder some of his rivals. Finally convicted of these murders, the Last Don turned around and became a government witness, helping the Feds gather evidence to indict his own successor. While the Bonanno family still exists today, they no longer control the vast criminal empire that they used to.

3The Last President Of Kongo Gumi

Kongo Gumi was a family-owned Japanese construction company that was founded in A.D. 578. The company specialized in building Buddhist temples, which was steady enough work to keep the company in business for a very long time—over 1,400 years. During this time, ownership of the company stayed within the Kongo family, following the Japanese tradition of passing the reigns to the family member deemed best able to lead the company.

But starting in the 1990s, the modern world finally caught up with Kongo Gumi. Kongo Gumi lost money in bad real estate deals at the same time that demand for its services finally began to decline. Masakasu Kongo, the company’s 40th president, had to make the difficult decision to lay off workers. When debts continued to increase, he finally sold the company, making him the last Kongo to run the company. Kongo Gumi still exists, but it’s now a subsidiary of a larger Japanese construction firm.

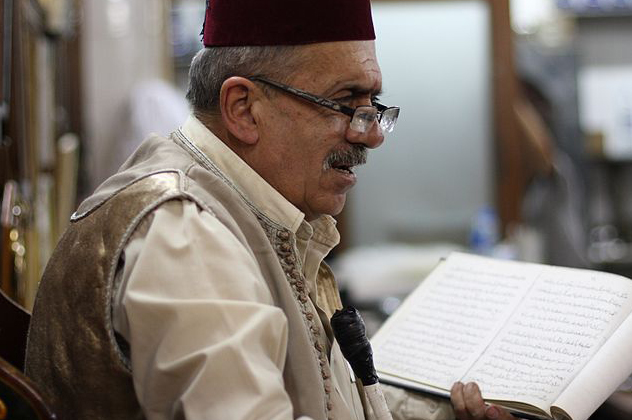

2The Last Hakawati

Another storytelling tradition that is dying out is a Syrian tradition called Hakawati. Like Awang Batil, Hakawati is part performance and part history, with the performer (confusingly also called a hakawati) using props, accents, and even audience participation to tell stories from Arabic history. What’s interesting about Hakawati is its nature—rather than traveling around, the hakawati always operates out of the same coffeehouse or cafe, with the audience traveling to see him. Hakawati stories are serial in nature and often take multiple readings to complete, a feature common to Arabic epic poetry. The stories, many of which are known in English as A Thousand and One Nights, are also told in a unique colloquial style, helping to make them more accessible.

Abu Shadi was believed to be the only remaining hakawati in Syria. Most of his audience constituted men in their sixties who had been coming to see Hakawati performances since childhood. He believed that one reason for the decline of Hakawati was that the storyteller best connects with audience members who are regulars—people who respond well to him and vice versa. Changing demographics in Damascus and other cities led to a drop in regulars at Abu Shadi’s cafe, but he proudly kept the tradition alive until he passed away in 2014.

1The Last Jew In Afghanistan

Zablon Simintov is the owner of a small kebab house in Kabul. The kebab house is inside a synagogue that Zablon is hoping to renovate. He is the last Jew in Afghanistan.

In the chaos that has engulfed Afghanistan over the past 20 years, many religious minorities have all but disappeared from the country. Afghan Christians are gone, and Hindus are vanishing as well. Zablon has been Afghanistan’s last Jew since 2005, the last of a religious community whose history stretches back 11,000 years.

Because he still feels a kinship with his country, Zablon stayed behind while his wife and children emigrated to Israel. Although he is well known in his neighborhood, he still takes precautions, such as removing his skullcap when he goes out and not advertising the fact that his restaurant is run by a Jew. However, his restaurant has been losing money ever since the US occupation ended, and Zablon is resigned to the fact that he may have no choice but to leave the country.