Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Crime

Crime 10 Terrifying Serial Killers from Centuries Ago

Technology

Technology 10 Hilariously Over-Engineered Solutions to Simple Problems

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Ironic News Stories Straight out of an Alanis Morissette Song

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Politics

Politics 10 Lesser-Known Far-Right Groups of the 21st Century

History

History Ten Revealing Facts about Daily Domestic Life in the Old West

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Everyday Products Surprisingly Made by Inmates

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Actors Dragged out of Retirement for One Key Role

Creepy

Creepy 10 Lesser-Known Shapeshifter Legends from Around the World

Animals

Animals 10 Amazing Animal Tales from the Ancient World

Gaming

Gaming 10 Game Characters Everyone Hated Playing

Top 10 Animal Endlings: The Last Of Their Kind Before Extinction

It is no secret that numerous animal species have gone extinct since humans have been around. When only one animal is left that belongs to a particular species, it is called an endling. When the endling dies, the species is gone forever.

There is something especially solemn about looking an endling in the eye. Telling their stories will help us remember them and serve as cautionary tales of how fragile life can be.

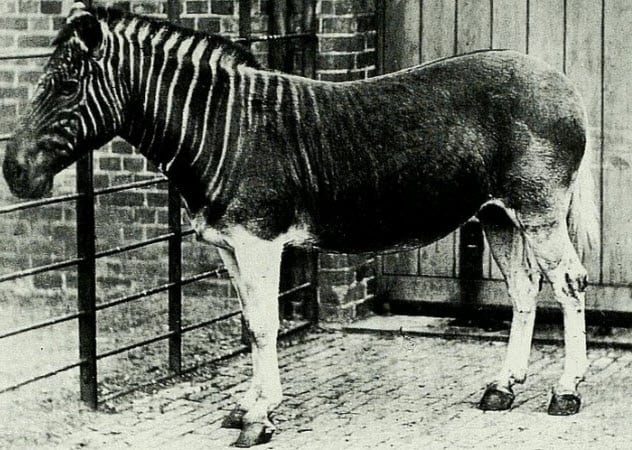

10 The Last Quagga

Equus quagga quagga

The last quagga to walk on Earth died at the Amsterdam Zoo in 1883. If you were to imagine the front half of a zebra and the back half of a donkey, you’d be fairly close to imagining a quagga. But fortunately, you don’t have to because photographs were taken of this zebra-esque mammal in 1870. They once roamed free in herds among the regions of what is today South Africa, but their extinction resulted from overhunting for meat, skins, and sport.

Thanks to the efforts of researchers in the 1980s, some of the mitochondrial DNA that made up this unusual creature was recovered. They extracted it from dried muscle tissue dating from 140 years before the experiment was conducted. It had been safely stored in a museum for that duration.

This mitochondrial DNA sequencing was the first-known demonstration that clonable DNA could be extracted from long-extinct critters, which opened up exciting possibilities. Not the chance of creating Jurassic Park as much as “building an accurate family tree of species across time.”

But hey, it is still fascinating science. Looking at the quagga mitochondrial DNA revealed that it was very closely related to the plains zebra—enough so that the quagga is now considered to be a subspecies.[1]

Inspired by DNA revelations, a project has been underway since 1987 to “breed back” the quagga through selectively breeding plains zebras with reduced striped patterns. These new equine animals are called Rau quaggas after the project’s founding researcher, Reinhold Rau. While they may not be entirely quagga on the inside, the resemblance is undeniable on the outside.

9 Incas The Carolina Parakeet

Conuropsis carolinensis

If you were told that the Eastern United States was once home to a poisonous species of parrot, you might have a hard time believing it. And it isn’t as if we could prove it to you by showing you one in person because the last one, named Incas, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1918. These gorgeous birds began life mostly green in color, but they developed beautiful shades of yellow and red on their heads as they aged.[2]

A journal article from 1891 describes a peculiar trait that led to the rapid disappearance of this species. Flocks of parakeets would often attack farmers’ crops, such as fruit orchards, either to use as a food source or out of “pure mischief.” The farmers would then shoot at the birds.

But instead of flying away to safety, the birds would return to where they had been targeted. This allowed farmers to eliminate entire flocks of these pesky and apparently fearless animals.

As for the poison, the birds seemingly acquired it secondhand after eating young cockleburs as a major food source. These plants contain the highly toxic chemical carboxyatractyloside. The famous ornithologist John James Audubon noticed that cats which ate the birds apparently died.

Potentially, this adds the Carolina parakeet to the very short list of poisonous bird species, which also includes the still-living hooded pitohui from New Guinea, the spur-winged goose of Benin, and a small number of others.

8 Celia The Pyrenean Ibex

Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica

The Pyrenean ibex was a species of wild goat that was once found in Spain, Andorra, and France. The last living individual was a female named Celia, who was 13 years old when she unfortunately died after being crushed by a falling tree in the year 2000.

Celia was well-known to researchers. She had been captured in 1999, and some cells had been taken from her ear. As it was known that ibex didn’t do well in captivity, Celia was fitted with a tracking collar and released back into the wild. That way, researchers would know her whereabouts. It also allowed them to find her body after she died.

A few years later, the Pyrenean ibex had the honor of being the first extinct animal to be successfully cloned thanks to the cells taken from Celia’s ear before she died. Of more than 50 attempts to artificially impregnate a different species of wild goat with a Pyrenean ibex embryo, only a single animal successfully carried the pregnancy to term.

The clone was born via cesarean section. Unfortunately, the resulting animal lived for only a few minutes due to a lung defect.[3]

7 Turgi The Snail

Partula turgida

In January 1996, a species of tree snail quietly went extinct when the last-known individual of a Polynesian species, Partula turgida, died at the London Zoo. For biologists, it was exciting that this was the first-known case of a parasite wiping out a species.

The numbers of this species slowly went, as snails do, from 296 to just one over the course of 21 months. That final snail, nicknamed Turgi by the staff, was one of the specimens autopsied to look for answers as to why they all died in captivity. The answer was a parasitic infection found in all the examined snails. Apparently, it led directly to their deaths.

Turgi’s tragic tale was neither the first case of tree snail extinction nor was it the last. In fact, of the 61 species of tree snails that were originally found on the Society Islands, including Tahiti, the majority of them are now extinct. A few species of the genus Partula are still kept in zoos around the world, but most species are extinct in the wild.

The extinctions were mostly caused by the introduction of another species of snail which hunted these native snails as prey. It is unfortunate that these critters are gone because they were an excellent example of how animals that are isolated on different islands can evolve into a wide variety of species.[4]

This is featured in Henry Edward Crampton’s 1916 book, Studies on the Variation, Distribution, and Evolution of the Genus Partula. Now, for most of the species, only the colorful shells remain on the islands they once called home.

6 Booming Ben The Heath Hen

Tympanuchus cupido cupido

Closely related to the prairie chicken, the heath hen was a ground-dwelling bird that was native to the East Coast of North America. They were especially plentiful in colonial America, especially in the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions.

The settlers of what would become the United States did not consider the heath hen to be a remarkable bird. In fact, many considered it to be a poor person’s food due to the abundance of these animals at the time. Some scholars even suggest that the birds eaten at the first Thanksgiving dinner may have been heath hens instead of the turkeys that we usually associate with the holiday.

Even though conservation efforts were underway to save the species, a series of bad circumstances led to a rapidly declining population. These events included a severe forest fire, an increase in natural predation, poultry disease, and severely cold winters.

But the ultimate factor spelling disaster for these colorful grouse was a lack of genetic diversity among the remaining individuals. In an unfortunate twist, all the females died out, leaving the males to strut around and do their mating ritual dances for nobody in particular.

Eventually, only one male was left and he was nicknamed “Booming Ben” in reference to his booming call. As described in a 1931 journal article, he would strut around Martha’s Vineyard, displaying his “weird courtship performances.” Sadly, he was last seen in 1932 and no additional sightings of this once-common bird could be confirmed.[5]

5 Toughie The Rabbs’ Fringe-Limbed Treefrog

Ecnomiohyla rabborum

The most recent death on this list is that of Toughie, the last-known member of a rare frog species called Rabbs’ fringe-limbed treefrog. He died in 2016 after 11 years in captivity at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

The name “fringe-limbed” comes from the extensive webbing on the animals’ fingers and toes which they used to glide from tree to tree. They were large for tree frogs, measuring almost 10 centimeters (4 in) when at their largest. This extinction is especially sad because this species was only discovered and named in 2008, so scientists knew about them for less than a decade.[6]

These frogs and many other amphibian species located in and around Panama suffered a mass dying-off as a result of a fungus that preyed upon their kind. Beginning in the 1980s, this fungus, called Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, slowly spread across the country.

In the 2000s, scientists estimated that the disease had the potential to kill off around 50 percent of amphibian species in the area. Conservationists tried to act before all these species croaked, but the fungus continued to spread despite their best efforts.

4 Benjamin The Tasmanian Tiger

Thylacinus cynocephalus

The thylacine (aka the Tasmanian tiger) was an unusual marsupial about the size of a dog. It had a pouch on its belly and stripes resembling those of a tiger on its back and behind. Despite having been extinct for over 80 years at this point, it is still a widely known cultural icon, especially in Oceania.

Much has been written about the Tasmanian tiger when it comes to humans regretting the extinction, but not as much attention has been paid to poor Benjamin, the Tasmanian tiger endling. The name Benjamin was seemingly given to him after his death, once people noticed that he was the last. But the zoo didn’t realize that he was an endling while he lived.

For many years, it was debated whether the last Tasmanian tiger was male or female. But the debate was settled in 2011 when a still frame from some 1933 footage of the animal moving around was analyzed in greater detail, revealing the anatomical truth that this thylacine was male.

His death in 1936 could have been prevented if his caretakers had been paying attention to the fact that he had been locked out of his sleeping quarters during harsh weather in the first week of September.[7]

Unfortunately, without access to better shelter, he died due to this neglect. No other individual animals were ever confirmed to exist. However, rumors persist to this day that Tasmanian tigers may still live in hiding in remote regions of Australia, New Guinea, or Tasmania.

3 The Last Kauai O’o

Moho braccatus

One of four extinct species of o’o (pronounced “oh-oh”) in the Moho genus, the Kauai o’o has one of the saddest extinction stories of any species. These birds were once plentiful on the islands of Hawaii, where their sleek black plumage was used for glossy decorations of traditional headwear for the islanders.

The decline of the species is usually attributed to mosquito-borne illnesses, such as avian malaria, as well as the introduction of rats, cats, and other predators to the islands.

What was believed to be the final mating couple of these birds made their home in the Alakai Swamp on the island of Kauai until Hurricane Iwa most likely killed the female in 1982. The male bird, the last of the species, survived on his own for at least a few more years.

He was last seen in 1985, and his final birdsong—to which no female would ever answer—was recorded in 1987. As part of a birdsong archive, a recording of this bird’s song from 1975 can be heard online.[8] The haunting melody of a species permanently lost is at once beautiful and devastating to listen to.

2 Martha The Passenger Pigeon

Ectopistes migratorius

The passenger pigeon earned its name from its great migrations which contained birds numbering in the billions. Yes, that’s billions with a “b.” When the flocks were at their greatest numbers, estimates placed passenger pigeons as the most populous bird in the United States. They made up 25–40 percent of all birds in the country. Incredibly, between 1860 and 1914, hunters and habitat destruction reduced the once seemingly impenetrable flock to a single bird.

Early descriptions of passenger pigeon flock migrations are worthy of legend—none more so than the story of an 1813 flock in Kentucky written by John James Audubon. This flock filled the air for three straight days, blocking out the Sun as they flew continuously through night and day over the Ohio River.

Audubon compared their droppings to snowfall. The hunters in the surrounding area could shoot into the air without aiming and bring home more than enough poultry to feed their families.

But this abundance, coupled with the birds’ taste for commercial crops, made them a nuisance. It wasn’t long before extermination attempts began which treated the passenger pigeon like a pest.

By 1900, none remained in the wild and the few left in captivity were dwindling. The final pigeon was named Martha. When she died in 1914, it spelled the end of a species that was once seen as impossible to exterminate.[9]

1 Lonesome George The Pinta Island Tortoise

Chelonoidis abingdonii

You can’t make a list about the last of a species without mentioning Lonesome George, easily the highest-profile case among endlings. George was discovered all by his lonesome in 1972 on Pinta Island, one of the Galapagos Islands.

After years of exhaustive searches turned up exactly zero more members of his species, he was officially declared the last remaining Pinta Island tortoise. The island’s vegetation had been ravaged by feral goats and pigs, which had been left behind by visiting humans. This made it impossible for the slow-moving tortoises to make a living. As a result, the rest of them died, leaving only George.

Lonesome George was placed in an enclosure at the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island. But he wouldn’t remain lonesome for much longer. Female tortoises from a closely related species were added to his pen to keep him company. Despite many attempts to produce a hybrid heir to George’s name, all the eggs laid by the females turned out to be infertile.

George died unexpectedly from natural causes on June 24, 2012. He was young for a tortoise, believed to be only around 100 years old. Galapagos tortoises can live to their 150s. When his death was announced, the tragedy brought visitors and workers alike to tears.[10]

Although the last purebred Pinta Island tortoise is gone, there is still hope for future crossbreeds. Seventeen Pinta hybrids were discovered on a different island after George’s passing. Ambitious experts are proposing breeding programs to maximize as many of the original Pinta traits as possible before reintroducing the animals to Pinta Island to stabilize the ecosystem there.

So, it is possible that a de-extinction attempt might just be within the realm of possibility.

Alexander R. Toftness runs a YouTube channel where Everything Is Interesting, or he can be found at alexandertoftness.com

Read more fascinating stories about extinct animals on 10 Extinct Animals With Surprising Attributes and Top 10 Extinct Animals That Scientists Want To Bring Back.