Humans

Humans  Humans

Humans  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptions That Brought Popular Songs to Life

Health

Health 10 Miraculous Advances Toward Curing Incurable Diseases

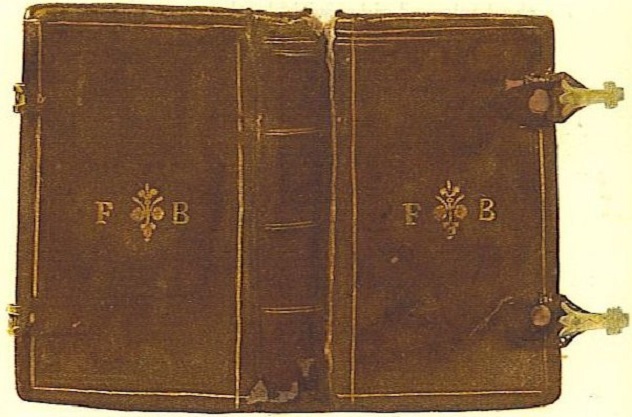

10 Surprising Facts About America’s First Book

The first book published in what is now the USA was a Puritan hymnal called The Bay Psalm Book. Published in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1640 by Stephen Daye, The Bay Psalm Book was a collection of holy songs translated from the Old Testament’s Hebrew into English. Because the printers were not trained typographers, the book is rife with typos, plagued with spacing errors, and crudely laid out over its 37 sheets. Here are 10 surprising facts about The Bay Psalm Book.

10 The Book Was Crowdfunded Long Before Kickstarter

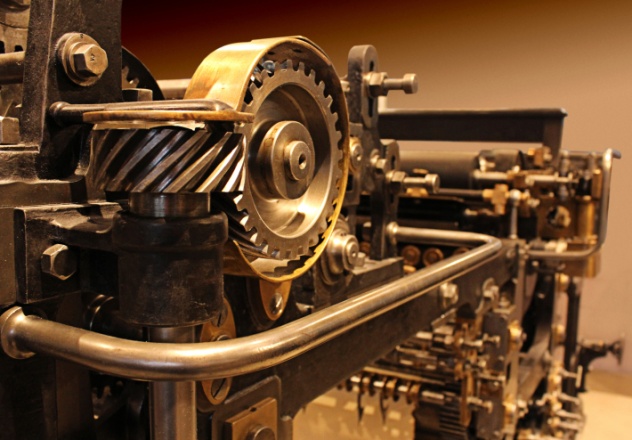

In the late 1630s, Reverend Joseph Glover decided to move from Sutton (in London, England) to the Massachusetts Bay Colony with his wife Elizabeth Harris Glover. Joseph and Elizabeth desired the greater religious freedom that Massachusetts Bay would provide. To prepare for this move, Joseph gave sermons to raise money and, with that capital, he bought type so that he could start a printing press. Printing presses were large, expensive machines that required multiple parts to run. Furthermore, establishing a printing shop required considerable resources, including type, ink, galleys, tables, frames, and paper, all of which had to be brought from England.

In addition to the money he raised from his parishioners, Joseph raised £49 for his printing house from seven of his friends in England and Holland: Major Thomas Clarke, Captain James Oliver, Captain Allen, Captain Lake, Mr. Stoddard, Mr. Freake, and Mr. Hues. In addition to the money he collected from his supporters, Joseph kicked in £80 of his own money, supplying £20 for the press and £60 for paper and ink.

9 The Uneducated Locksmith Who Somehow Ran A Printing Press

On June 7, 1638 in London, Joseph Glover wrote up a contract with Stephen Daye, an indentured locksmith, making Daye the operator of the press. Joseph and Elizabeth left England with their children, their servants, Daye, his family, and three workers. This group, with a printing press, arrived in Massachusetts in the summer of 1638—minus one person. Joseph Glover never made it to the New World because he died of a fever at sea while en route to New England. Accordingly, Elizabeth established the printing press in the Cambridge, Massachusetts house of Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard University.

Although most scholars give Daye, who was 44 years old in 1638, the credit for being America’s first publisher, they can only speculate on his exact duties and responsibilities at the Cambridge Press. We lack concrete facts about Daye, and some historians argue that no proof of him being an apprentice to a London printer exists. Nevertheless, publisher and author Isiah Thomas (1749–1831) mentions that Daye was an apprentice to a London printer. If Daye was indeed a locksmith and lacked knowledge of typography, then perhaps Joseph could not afford to hire any skilled typographers or could not find any who would move to New England from London.

8 The Most Expensive Book Ever Sold At Auction

The Bay Psalm Book sets the record for the most expensive English language book ever sold. Back in 1947, a copy of the book sold for an unexpectedly high amount—$151,000—at the Parke-Bernet Galleries auction in Manhattan, after competing bids between Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney and The Rosenbach Company (on behalf of Yale University) drove up the sale price.

The Bay Psalm Book sets the record for the most expensive English language book ever sold. Back in 1947, a copy of the book sold for an unexpectedly high amount—$151,000—at the Parke-Bernet Galleries auction in Manhattan, after competing bids between Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney and The Rosenbach Company (on behalf of Yale University) drove up the sale price.

On November 26, 2013, the book broke records again, displacing The Birds Of America by John James Audubon (which sold for $11.5 million in December 2010) to become the most expensive book ever sold at auction. David M. Rubenstein of the Carlyle Group, who also owns a copy of the Magna Carta, purchased the book from the Sotheby’s auction for almost $15 million. The Bay Psalm Book holds this record because it’s the first book published in America and because it’s so rare—there are only 11 surviving copies today.

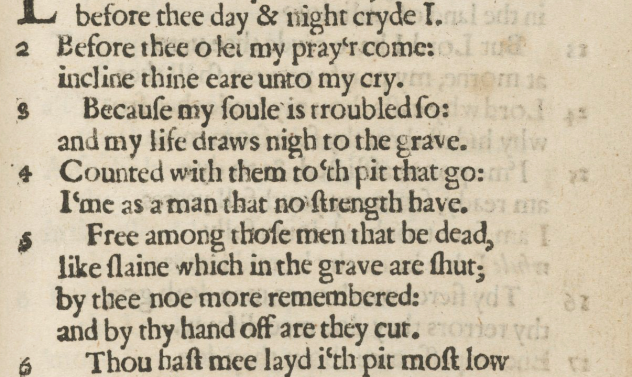

7 The Authors Were Terrible Writers

The writers of The Bay Psalm Book knew their translations were obviously bad. Thomas Welde, John Eliot, Richard Mather, and John Cotton, prominent members of the Massachusetts clergy, desired a more literal translation of Hebrew than the 1562 Whole Book of Psalms that was used at the time. In 1636, Welde, Eliot, and Mather each began translating portions of Hebrew into English verse.

Because these men were not poets, their writing in The Bay Psalm Book is uncomfortably and awkwardly literal. In total, 30 clergymen contributed to the book, but Welde, Eliot, and Mather were the main writers. In the book itself, Mather apologizes in a disclaimer for the quality of the verses, and this apology is the oldest surviving prose that was both written and printed in America. Although historians have snubbed the poetry’s clumsy turn of phrases and forced rhymes, the book’s stanzas helped readers memorize the hymns during a time when literacy was low, and books were not readily available.

6 A Woman Was In Charge

It was extremely unusual for women to be owners or proprietors of businesses in the 1600s (and in later centuries). Some historians give Elizabeth Glover the sole credit for establishing the first publishing house in the 13 colonies. Although Elizabeth’s prominent role as the proprietress of the Cambridge Press was due only to her husband Joseph’s unexpected death, some historians call Elizabeth the Mother of the American Press. Since Elizabeth was the owner of the press, it seems that Stephen Daye was the manager.

We don’t know all the details about Elizabeth’s involvement in the press, but a good clue for the extent of Elizabeth’s role in the press is that after her death in 1643, the Cambridge Press became Harvard’s property and was later dismantled. The fact that neither Stephen Daye nor his son Matthew, who also worked at the press, continued running it after Elizabeth’s death indicates her high level of involvement—both financially and operationally.

5 The Book’s Popularity Spread Back To Europe

New England in 1640 consisted of 50 towns and 25,000 people total. Because all Puritans in Massachusetts used it, The Bay Psalm Book sold like wildfire among its large audience of religiously minded colonists. In fact, in 1647, Daye and Glover published a second edition, probably because they sold all 1,700 copies of the first edition, presumably using all of the paper they brought from England. Sold in stores and available at churches, The Bay Psalm Book had a surprisingly large geographical reach; books printed in colonial Cambridge were distributed widely by private individuals and commercial publishers from New Hampshire to Barbados.

The Bay Psalm Book was popular in New England for a century, and it was also read in Philadelphia, England, and Scotland. In fact, of the more than 50 editions of the psalm book, half were printed in England, which reveals its popularity and surprising cross-Atlantic appeal. The Puritans in Massachusetts fled England for religious freedom, and the first book they produced ironically became popular back in England.

4 The Whole Book Is Kind Of A Mess

Because Stephen Daye and Elizabeth Glover were not trained typographers, they didn’t really know what they were doing, so they improvised when necessary. Leafing through The Bay Psalm Book, you would immediately find spelling errors and odd spacing. Commas were used upside down for apostrophes, indicating that Stephen Daye and Elizabeth Glover didn’t have a block of type for apostrophes. They apparently improvised by flipping the block for commas.

The book contains mostly Roman but some italic type, differing font sizes, and some Hebrew and Greek characters interspersed with the English text. Hebrew letters, which appear in the preface and throughout the book, were probably cut on special blocks of wood or metal. The printers bound some of the pages in the wrong order, and pagination is inconsistent. Pages are unnumbered but contain, in their bottom-right corners, either the first word or a part of the first word of the following page.

3 The First Printed Music In British North America

In Boston in 1698, two printers named Bartholomew Green and John Allen published the ninth edition of The Bay Psalm Book, which is significant since it contains the first printed music in British North America. We can assume that before 1698, no printing presses were technologically equipped to print sheet music, so Green and Allen presumably had to reset the type to add musical notations. The treble and bass of the 13 songs were printed on 63 wooden blocks, which were approximately 1 centimeter (0.375 in) high and 5 centimeters (2 in) long. Because the treble and bass for the same song sometimes appeared on different pages, the printer was probably musically illiterate. However, this seeming lack of musical knowledge could be due to technological limits, for the blocks were only so big.

Puritans regarded religious music as a tool with which to worship God—secular music was a dangerous distraction and waste of time, but religious music in harmony with God’s scriptures was useful. Puritans viewed the book as a direct connection to God, and they sang the psalms as a way to sing the literal word of God.

2 Colonial Printers Couldn’t Survive On Bookselling Alone

Print shops were rare in colonial America in the 17th century, so people had a limited choice of reading material, making books valuable. Educated lawyers and clergymen bought The Bay Psalm Book to express their newfound religious freedom, parents bought the book to teach their children hymns, and every congregation in the Massachusetts Bay Colony used it. The Bay Psalm Book was sold at the Cambridge Press’s office and at Hezekiah Usher’s Cambridge bookstore, the first bookstore in New England. Despite the book’s popularity and multiple editions, the Cambridge Press didn’t make enough money on book sales alone.

The Cambridge Press made the majority of its earnings by printing Harvard University documents, a Native American translation of the Bible, commissioned official documents, primers, catechisms, and almanacs. As opposed to those in London, print shops in the colonies also usually served as bookstores. In addition to printing books, printers needed to sell stationery, lottery tickets, and small musical instruments in order to bring in enough revenue. Booksellers even accepted payment in the form of corn, pork, or beef rather than currency.

1 A Counterfeiter Tried (And Failed) To Copy The Bay Psalm Book

The Bay Psalm Book wasn’t actually the Cambridge Press’s first publication. Although we don’t know exactly when the Cambridge Press opened, we do know that Elizabeth and Daye produced a broadsheet (a large sheet of paper) of “The Freeman’s Oath” in either February or March 1639. Daye printed this oath, which men over 20 years old took to become legal citizens of Massachusetts Bay, on paper resembling a poster. The Cambridge Press produced 50 copies of the oath, but none have survived.

The Bay Psalm Book wasn’t actually the Cambridge Press’s first publication. Although we don’t know exactly when the Cambridge Press opened, we do know that Elizabeth and Daye produced a broadsheet (a large sheet of paper) of “The Freeman’s Oath” in either February or March 1639. Daye printed this oath, which men over 20 years old took to become legal citizens of Massachusetts Bay, on paper resembling a poster. The Cambridge Press produced 50 copies of the oath, but none have survived.

In 1985, the counterfeiter Mark Hofmann attempted to forge a copy of “The Freeman’s Oath” and sell it to the American Antiquarian Society and the Library of Congress. Hofmann copied the ornamentation and typography used in The Bay Psalm Book. While he was waiting for experts to authenticate his copy of the oath, Hofmann was running out of money and unable to repay his debts or provide documents, so he built bombs and murdered two people: a document collector and the wife of the document collector’s former employer. The next day, one of Hofmann’s bombs exploded in his car, severely injuring him. In 1988, Hofmann began serving a life sentence in Utah State Prison.

Suzanne writes about indie music at After The Show.