Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

Mysteries

Mysteries 10 Devastating Missing Child Cases That Remain Unsolved

Creepy

Creepy 10 Scary Tales from the Middle Ages That’ll Keep You up at Night

Humans

Humans 10 One-of-a-kind People the World Said Goodbye to in July 2024

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Holiday Movies Released at Odd Times of the Year

Politics

Politics 10 Countries Where Religion and Politics Are Inseparable

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Freaky Times When Famous Body Parts Were Stolen

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Interesting Things Manufacturers Stopped Making and Why

Gaming

Gaming 10 Funny Tutorials in Games

History

History 10 Fascinating Little-Known Events in Mexican History

Facts

Facts 10 Things You May Not Know about the Statue of Liberty

10 Misconceptions About The Inquisition

It’s one of the darkest times in recent religious history. When people point to the dark side of the Catholic Church, the Inquisition is one of the first things that gets mentioned. It’s an unbelievably complicated piece of history, and it’s no wonder that a series of myths and misconceptions have grown around it.

10The Inquisition Was A Single Event

Thanks in no small part to Monty Python and Mel Brooks, when we think of the Inquisition we usually think of the Spanish Inquisition. It was, and still is, the most famous one, but it was by no means the only one.

The idea of the Inquisition has its roots much earlier than that. As early as the first century, Roman law made allowances for what they called “inquisitorial procedures.” The idea allowed for an investigation into a crime without the need for anyone to bring formal charges to the court. There were other familiar methods in place, too, like the right of the investigating parties to use torture on those they were questioning.

When Christianity arrived in the fourth century, the laws were simply expanded to cover religious matters as well as secular. Bishops were carrying out Inquisitions, albeit on a small scale, from the beginning of Christian history.

By 1184, Inquisitions were more formalized with Pope Lucius III changing the idea from a passive one to a more aggressive means of finding and exterminating heresy. Throughout the Middle Ages, religious orders were formed with specific groups that were meant to act as inquisitors. But here their purpose was to correct behavior rather than punish it. That would change drastically in Spain a few hundred years later with the Spanish Inquisition.

9The Pagans And The Jews

Usually, when we think of the targets of the Inquisition, we think of those that still worshiped the pagan gods and the Jews. While they certainly were a huge part of what the Inquisitions were trying to destroy, they weren’t the first targets.

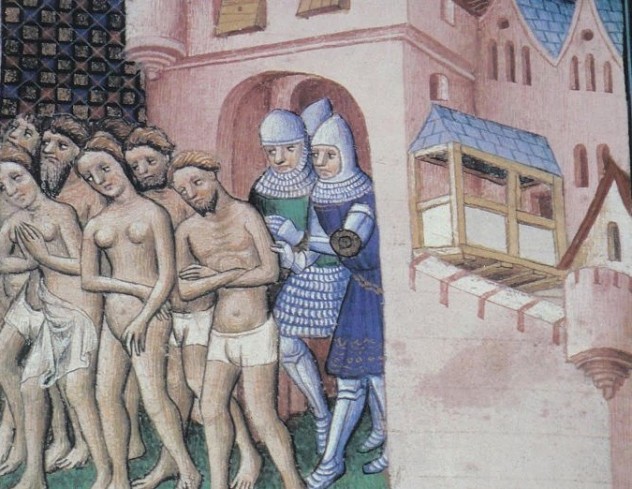

One of the first groups of people specifically targeted by an Inquisition was another group of Christians: the Cathars. The Cathars rejected everything about the structure of the Roman Catholic Church, especially their displays of wealth and power. The persecution of the Cathars started in earnest and en masse with Pope Innocent III’s sacking of Toulouse. When soldiers were ordered to kill the Cathars and said that they couldn’t tell who was Cathar and who wasn’t, they were told to just kill everyone and let God sort them out.

At about the same time, the Pope was also declaring his condemnation of another Christian group, the Waldensians. The group had a handful of beliefs that the Roman Catholic Church deemed heretical, including a disbelief in the idea of purgatory and the idea that anyone could consecrate wine and bread. In the face of Pope Innocent III’s Inquisition, most headed up into the mountains of Italy. They would remain active for a few hundred more years, but they would eventually fall victims to accusations of witchcraft at another later Inquisition.

8It Was Around Longer Than You Thought

At its heart, the Inquisitions weren’t necessarily about torture and death; they were about rooting out heretical thoughts and actions. Part of that meant keeping an eye on not just what people were doing, but what they were reading. This led to the Index of Prohibited Books. The first official version of the list was published under Pope Paul IV in 1559, and it was controversial even when it was first introduced. The idea had its roots several decades earlier, and for the next four centuries, it would be an ever-evolving work in progress.

While unapproved religious texts made up a good amount of what the list deemed heretical, there were a huge number of pretty surprising entries that made the list. Among some of the entries are the works of Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, Daniel Defoe, and Jonathan Swift. Most philosophers—Descartes, Mill, Kant, and Sartre, to name a few—were also on the list. And, it was only in 1966 that the Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith stopped publishing and adding to the list, although they did say that while it wasn’t official anymore, those that were truly good, moral people would continue to use it as a guideline for what they shouldn’t be reading.

As for the organization that was the Inquisition itself, that’s still around, too. That Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith? It’s almost a modern name for the Inquisition. According to the Vatican, the purpose of the group is to defend the Church against heresy, and they freely claim to trace their roots back to the Sacred Congregation of the Universal Inquisition as it was established in 1542.

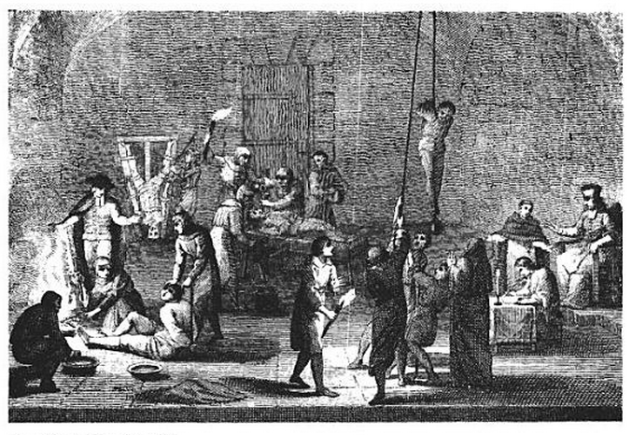

7The Banning Of Torture

It’s probably the thing that the Inquisitions are most known for, but torture hasn’t always been such a clear-cut and widely accepted method in the Church’s arsenal. Some of the earliest writings on the idea of freedom of religion (like the fourth-century writings of apologist Lactantius) state that anyone who would defend their religion by torture isn’t upholding their beliefs at all, and they’re disrespecting them in the most unforgivable way possible. In its original incarnation, the Inquisition wasn’t meant to use torture or the punishments that they would later become famous for.

In the 13th century, inquisitors were banned from administering torture. They could, however, be present in the company of secular representatives who were using it as a way to coax confessions out of the unwilling, although the nobility and the upper echelons of the educated were exempt from torture. It was only in 1252 that Pope Innocent IV gave members of the Inquisition the power to administer torture as a way of extracting what they thought was the truth.

Even then, torture was for the most part only acceptable if no blood was spilled, if there was no permanent damage to the limbs, and if there was no chance of death. This, of course, only required torturers to be creative with their methods, and after only eight years, the next Pope made allowances for the off chance that mistakes would happen.

6The Number Of People Executed

Just how many people died during the Inquisitions has long been up for debate. Some claim millions were killed by the Inquisitions, while others claim tens of thousands. According to the official statement released by the Vatican in 2004, it’s many less than what’s been suggested.

According to papers prepared by the Vatican, 125,000 people were put on trial by the Spanish Inquisition—and only about 1 percent of them were executed. The findings were released at the end of a process that began in 1998, searching Vatican records and compiling what was found on the Inquisitions. The same study found that around 25,000 people were executed in Germany for witchcraft, but most of those weren’t actually tried during the Inquisition itself. The small country of Lichtenstein told a sad story. Only 300 people were put to death by the Inquisition there, but at the time, that was about 10 percent of their entire population.

The Vatican also issued statements saying that absolutely none of it was acceptable, with Pope John Paul II apologizing for the actions of the Church in the past. Interestingly, while he apologized for the actions and what happened during the Inquisitions, he didn’t apologize for the actions of previous popes, which would have broken a rather cardinal rule of not admitting the actions of earlier popes might have been less than ideal.

5The Inquisition In The New World

The Spanish Inquisition had an incredibly far reach. Far from being contained only to Europe, all of the Spanish colonies in the New World had to answer to the Inquisition as well. At the time the monarchies of Europe were scrambling to stake their claims in the New World, Spain’s Ferdinand and Isabella were among the most determined of the supporters of a single nation united under the Catholic Church. It was under their rule that the infamous Spanish Inquisition truly came to power. The notorious Torquemada was the queen’s own personal confessor, after all.

Even as Spain and Portugal were colonizing the new continent, those that were being persecuted by the Inquisition there found numerous ways to escape to the New World; many settled in areas like Lima, and the Inquisition followed. By the 1520s, official authorization had come down the line, allowing missionaries and monasteries to perform all the duties that were deemed necessary of the Inquisition.

One of the largest museums in Peru today is the Museum of Congress and Inquisition. Opened in 1968, the museum still resides in the building that was once used by the Spanish Inquisition. The rooms where confessions were once heard, torture was once carried out, and the cells where people once served their sentences still serve as a grisly reminder of Lima’s Spanish heritage.

4Everyone Expected The Inquisition

It might have been hilarious when Monty Python did it, but the idea of the Spanish Inquisition showing up on your doorstep, completely unannounced, and dragging people away to their interrogation chambers is an absolutely terrifying idea. It didn’t quite happen like that, though, and everyone really did sort of expect the Spanish Inquisition.

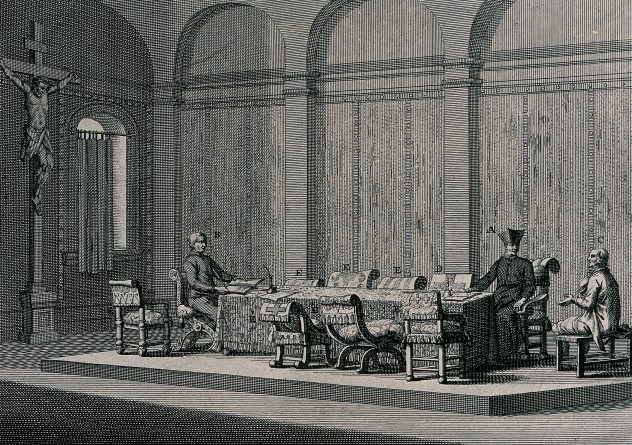

When the Inquisition set up shop in an area, the first thing they did was announce what they were going to do. Before 1500, they read an Edict of Grace and, after 1500, it was an Edict of Faith. The message was basically the same thing, though, and it made it very clear what they were going to be doing.

The edicts gave members of the community anywhere from two weeks to a few months’ warning before the tribunal started to get to work. Anyone who was a heretic was encouraged to present themselves to the tribunal and confess. When the time limit was up, they were going to start asking questions, and people were going to start telling on each other. It was one thing to confess your sins, but your problems really started when someone else was telling on you.

It’s thought that a huge number of personal confessions weren’t done out of any real committing of heresy, but instead, they were done out of fear of having neighbors pointing fingers at people they didn’t really like, which was a very real fear, as it was all done in secret. Evidence was gathered and weighed, and then it was time for the Inquisition to come knocking on doors . But it was never a surprise.

3The Conflict Of The Black Legend

History is a funny thing, and it’s so hard to get a completely honest telling of what actually happened. According to the Spanish journalist Julian Juderias, a lot of what we know about the Spanish Inquisition (or think we know) is actually part of a massive smear campaign spearheaded by nations that just don’t like Spain very much.

It’s a fairly new idea as he was only writing this in 1912. According to Juderias, most of the criticisms and the horror stories about the Spanish Inquisition come from well after the movement was in its heyday, with accounts really starting to appear in the latter half of the 16th century. Juderias believed that what we know about the Spanish Inquisition might only be a little bit of the truth, and that most of our histories have been written by accounts from other European Protestant nations that were eager to paint the Spanish Catholics in a pretty dark light. He said that it wasn’t just the Inquisition that got the negative treatment, it was everything about Spanish culture, especially their adventures in the New World and their exploitation of the people they met there.

The treatment of Catholics by the Reformers would be likened to a strange sort of Inquisition itself, and it’s all cited as supporting the idea of the so-called Black Legend. Once the Protestant movement began gaining strength and targeting the now-heretical Catholics, the whole thing not only got flipped on its head, but it’s used to put the idea of the Inquisition, and what we know about it, in a whole new light.

2Willing And Unwilling Conversions

Being deemed a heretic didn’t automatically mean that you were tortured or that you received a sentence of death or exile. In 1391, a series of riots broke out in the south of Spain, and in the end, somewhere around 20,000 people officially converted to Catholicism. The act was kind of a double-edged sword.

As Jews, the Catholic Church actually had no jurisdiction over them and no real recourse to officially impose their views on them. Once they converted, though, they were under the wing of the Church and needed to be at least seen acting and believing in the right way. When that didn’t happen, that’s when the Inquisition stepped in.

The converts were called conversos along with their children and their grandchildren. They were always thought of as lesser Catholics because of their once-Jewish pasts, but their conversion also opened some doors. There were some jobs that were only available to Catholics and plenty of opportunities in the economic world that were off-limits to anyone who wasn’t the right religion.

Within a generation’s time, the conversos of the 1391 riots would form Spain’s new middle class, and that was a problem. That meant that they were moving up in the world a little too quickly for people that no one truly believed just yet, making it much more important that the Church keep an eye on them to make sure they were attending their confessions, communions, and baptisms as promised.

1The Survivors

There were people that fought the Inquisition and won, like Maria de Cazalla. Proceedings against her began in 1526 and she was arrested in 1530 with evidence that included personal testimonies against her. A member of the upper class and the sister of a bishop, she was also a converso, a label that should have acted against her. In 1534, she was found guilty on a few charges, including being a follower of the Protestant ideas, putting the religious authority of a mortal woman above the saints, and claiming that sex was a more religious experience than prayer.

Over the next few years, she endured torture, imprisonment, and countless interrogations. Never accusing anyone else of heresy, she also never confessed and always maintained her innocence. In the end, the tribunal wasn’t able to establish any sort of concrete evidence against her. She painted her supposed “teachings” as discussions, her children as her maternal burden, and her actions all well within the confines of the church doctrines. Eventually, after almost a 10-year ordeal, she paid a small fine and was freed from the grip of the Inquisition. What happened to her afterward isn’t known, but she did survive persecution, torture, and testimonials, and she walked away.