Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Mysterious Deaths That History May Never Fully Explain

Sometimes, archaeologists are completely puzzled by what they find. Sometimes, they uncover clues to solve some of the mystery but leave us wanting more. Then there’s the rare discovery that serves up just enough clues to shake some of our identities to the core and potentially rewrite our history.

10The Swedish Skulls Mounted On Stakes

In 2009, archaeologists excavated an 8,000-year-old Stone Age settlement, known as Kanaljorden, near the town of Motala (pictured above, c. 1890) in southeast Sweden. The skulls and skull fragments of 11 people were found in a stone-encased mass grave at the bottom of a formerly shallow lake. Strangely, the bases of two of these skulls were impaled with wooden spikes. Other skulls seemed to have been mounted this way, too.

No one knows who these people were or why they were buried this way. Archaeologists also couldn’t explain why one woman’s skull had a second woman’s temporal bone shoved inside. They want to do a DNA analysis to see if the women are related.

Scientists proposed two main theories to explain their findings. First, it’s possible that the individuals were taken out of their graves after their flesh decomposed, then their skulls were mounted before being reburied in a second funeral. That’s consistent with a tradition observed at another Mesolithic site in Sweden. “We believe the stakes were used for mounting, with the aim to display the skulls better during the complex ritual,” said excavator Fredrik Hallgren. “The intact stake has a pointed end and was probably thrust into the ground—or possibly a bed of embers, since there are slight traces of fire—during a part of the ritual. The skulls were subsequently laid to rest at the bottom of the lake.”

The second theory is that the Swedes killed their enemies in battle and brought their heads home on stakes as trophies. Researchers believe a DNA analysis will tell them if the skulls are from local residents or distant strangers.

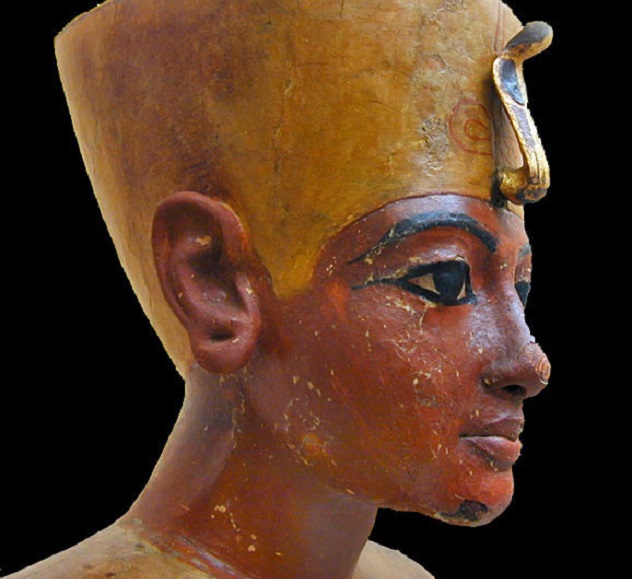

9The New Evidence About King Tutankhamun

Since his tomb was discovered in 1922, the cause of Egyptian king Tutankhamun’s premature death at 19 years old in 1323 B.C. has been the subject of endless debate. Some theories include a runaway chariot smashing into Tut, a crash while Tut was riding inside a chariot during battle or a hunt, an assault by a hippopotamus, and a kick from a horse. These types of theories arise from the massive trauma to the boy’s chest and, in the case of the hit by the speeding chariot, a series of injuries on one side of his body.

However, all of these theories assume that the trauma occurred when he died. Some experts believe that thieves from the 20th century caused that chest trauma. When the king’s tomb was unguarded during World War II, these experts believe that thieves cut through Tut’s ribs to steal the remaining beads that were stuck to his chest.

Now, a newer theory has been unveiled courtesy of a virtual autopsy of over 2,000 computer scans. Combined with a genetic analysis that shows his parents were brother and sister, this new explanation discredits many of the older theories, especially the one about dying in a chariot crash.

According to the results of the virtual scans, the only fracture to occur before Tut died was of his knee. He had a club foot which likely caused him to walk with a cane, a finding reinforced by the 130 used canes buried with him. “[We] concluded it would not be possible for him [to ride on a chariot], especially with his partially clubbed foot, as he was unable to stand unaided,” said Albert Zink, head of the Institute for Mummies and Icemen in Italy.

Instead, this new analysis suggests that King Tut died from serious physical weaknesses caused by genetic disorders from his parents’ inbreeding. Researchers want to do additional studies to gain more insight into his conditions. However, the young king also suffered from malaria, so they can’t rule out that disease as a contributing factor to his death.

8Sahara Skeletons In First Known Intercommunal Conflict

On the outskirts of the Sahara Desert in northern Sudan, archaeologists and anthropologists have been studying human remains discovered in the Jebel Sahaba cemetery east of the Nile River. (Lake Nasser, where the Nile crosses the border from Sudan to Egypt, is pictured above.) At 13,000 years old, these skeletons are the oldest ever found in a formal cemetery used for several generations in the Nile Valley. But more importantly, they may be victims of the first known intercommunal conflict in the world.

The relatively large conflict played out over many months or even years. Most of the victims died from wounds inflicted by enemies using flint-tipped arrows. That was evident by the many fragments from flint arrowheads embedded in or around the bones of the dead. There were also impact marks from the arrows.

“Ongoing research is also studying the velocity and directionality of the arrows and weapons based on cut marks and other microtraces on the bones, potentially allowing us to recreate the lethal raid. Clearly, the conflict was brutal and seems to have been fairly constant, as healed injuries have also been observed,” said Renee Friedman, curator of the British Museum where some of the skeletons have been displayed.

Scientists believe these individuals were ancestors of today’s African Americans. But so far, the identity of their attackers has not been established. It’s possible that their enemies were from a completely different race or ethnic group, with the most likely candidates being the North African/Levantine/European people who populated the Mediterranean Basin. Although they can’t be sure, researchers believe that the two groups may have been competing for scarce resources when a climatic downturn, the Younger Dryas period, killed plants and animals and dried up all permanent water sources except the Nile River.

7The Mysterious Poisoning Of An Italian Warlord

Initially, Renaissance warlord Cangrande della Scala of Verona was believed to have died in 1329 of a stomach ailment. But a modern autopsy of his mummy shows the cause of death was poisoning by digitalis (also known as foxglove), a plant that causes nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea in the early stages of ingestion and heart stoppage in severe cases of overdose.

When he died, Cangrande’s rule extended from Verona to his military conquests of Padua, Treviso, and Vicenza. Cangrande was also the main patron for Dante Alghieri, author of The Divine Comedy, an Italian poetic masterpiece that depicts a journey from the terrors of hell, including punishments for various types of betrayal, to the delights of Heaven. Was Cangrande himself betrayed?

In July 1329, 38-year-old Cangrande traveled to his recently conquered city of Treviso. A few days later, he developed fever, vomiting, and diarrhea. His symptoms progressed rapidly, with death coming just four days after he entered the city. According to sources from that time, Cangrande was believed to have died from drinking polluted spring water. There were some rumors of deliberate poisoning, but modern researchers dismissed them as legend even though Cangrande’s symptoms were similar to those of a foxglove overdose.

This latest autopsy solves one mystery. Researchers found foxglove pollen in the warlord’s rectum and toxic amounts of digoxin and digitoxin (both from foxglove) in samples of his feces and liver. They also determined that Cangrande drank chamomile and black mulberry tea before dying.

But that leads to another mystery. Did Cangrande ingest foxglove by mistake or was he deliberately poisoned to death? If it’s murder, the list of suspects includes rivals from Milan and Venice and even a power-hungry nephew, who succeeded Cangrande after his death.

6The Brutal Warriors Of Mesa Verde

In the late 1200s, the number of settlers in the central Mesa Verde area of Colorado declined in just three short decades from a population of around 40,000 to zero. A 2014 study from Washington State University may shed light on the unusual violence that preceded the disappearance of this culture from this location.

According to archaeologist Tim Kohler, almost 90 percent of the skeletons in the region from people who died from 1140–1180 showed evidence of trauma to their heads or arms. That means many of them died violent deaths. But the mystery is what caused such savagery, especially when the population just south of this region in the northern Rio Grande area (in New Mexico) was living peacefully.

Kohler and his associates noted that population booms occurred in the two areas simultaneously. However, Mesa Verde became more savage, while Rio Grande became more peaceful. Kohler thinks the difference may have to do with the development of specialized skills in Rio Grande. There, the individuals progressed from doing everything themselves to specializing in certain activities like arrow-making and weaving. Then they traded with each other, so they couldn’t afford to fight or they wouldn’t have survived. In Mesa Verde, almost no specialization occurred, so everyone was still independent and looked out for themselves. However, this theory is just speculation. We may never know what really happened.

A drought also drove settlers from Chaco Canyon north to Mesa Verde in the mid-1100s. “They were resisted,” Kohler said, “but resistance was futile.” Violence reached its highest point in Mesa Verde in 1160. Then, over a short period of time, the rest of the population left or died. As the area was being abandoned, archaeological evidence shows that two of the remaining pueblos in Mesa Verde were attacked. Many of the inhabitants died in the final battle.

5The Enemies Of The Maya

In the old Maya city of Uxul in Campeche, Mexico, archaeologists from the University of Bonn were excavating a site when they unexpectedly made a grisly find in a man-made cave that was once a water reservoir. They discovered 24 human skeletons, each of which was decapitated and dismembered.

The skulls were strewn all over the inside of the cave, not necessarily near the corresponding bodies. Many of the jaws were no longer connected to the heads. Hands and legs were also removed but sometimes entirely preserved. “This observation excluded the possibility that this mass grave was a so-called secondary burial, in which the bones of the deceased are placed at a new location,” said archaeologist Nicolaus Seefeld.

A violent death was provable for most of the victims. There were hatchet marks on many of the skulls as well as the cervical vertebra, which indicates decapitation. The victims were 18–42 years old when they died. Of the 24 remains, two were of women and 13 of men. The sex of the rest could not be determined. However, this gruesome discovery proves that the Maya did dismember their enemies as depicted in their artwork.

It remains a mystery as to who these people were and why they were so violently murdered. Some of them had jade tooth inserts which indicate high social standing. But it’s unclear if the victims were from Uxul or if they were prisoners captured from another Maya city.

4The Defleshed Woman Of Dewil Valley

As part of a bizarre burial ritual in the Philippines, an adult woman’s bones were defleshed, crushed, burned, and placed in a small box before being interred in the Ille Cave in Dewil Valley, Palawan, about 9,000 years ago. This is the first known cremation in Southeast Asia and is especially notable for its complex associated ritual.

From cut marks, archaeologists believe the people who buried her understood how to separate bones at the joints. But even more gruesome were the scrape marks on her bones that are evidence of defleshing, which means the skin and organs were removed so that only her bones remained. The larger bones—such as those from her arms, legs, and skull—were then smashed with some type of hammer or forging tool. Finally, all of the bones were gathered together for cremation.

However, no one’s sure what was done with this woman’s flesh. Did the people who buried her eat it? The researchers were reluctant to draw that conclusion because they felt it was too controversial an issue. Unless they find human gnaw marks, they’ll simply refer to the defleshing as a burial ritual.

3Mass Grave Of Sacrificial Children With Llamas

Archaeologists once believed that the Chimu culture of northern Peru made all their ritual sacrifices within the powerful and wealthy capital city of Chan Chan, which was conquered by the Inca in 1470. However, in 2011, the discovery of a 600-year-old mass grave containing the skeletons of 42 children and 76 llamas a short distance outside the capital near Huanchaquito has turned that belief on its head. It’s also presented archaeologists with some compelling mysteries that have yet to be solved.

Although the people of Chan Chan built a complex irrigation system that helped their city to flourish, this harsh desert region received only about 0.25 centimeters (0.1 in) of rainfall per year at that time. So water was always a precious resource to this community.

In the summer of 2014, archaeologists discovered more victims at the Chimu site. Although they believe all of these deaths occurred as part of a religious ritual, the researchers aren’t sure if the children died as a sacrificial gift to the ocean or as a reaction to an El Nino weather event that caused dangerous flooding. Either way, scientists believe the llamas were probably killed to carry the children to their afterlife. This mystery is especially tantalizing for the archaeologists because, until now, they’d only seen adult captives killed in this area.

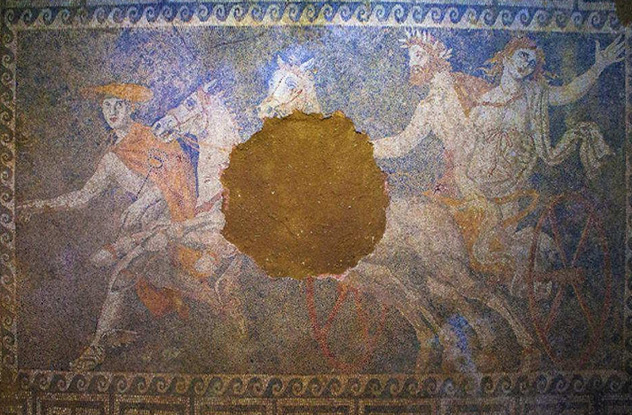

2The Kasta Hill Remains

In an intriguing mystery from the time of Alexander the Great’s death in the fourth century B.C., the identity of an approximately 60-year-old woman, whose remains have been found in the largest tomb ever excavated in northern Greece, has yet to be revealed. Is it Olympias, Alexander’s mother, who was executed by Cassander, one of the generals who took control of Alexander’s empire after his death? To secure his place on the throne, Cassander executed all of Alexander’s next of kin, including the still–politically powerful Olympias, Alexander’s wife Roxane, and her young son Alexander.

The ornate tomb, which reeks of royalty, is in Kasta Hill, where the ancient port city of Amphipolis was once located. So far, the burial chamber has yielded the remains of at least five people. In addition to the older woman, archaeologists have found two middle-aged men, a newborn whose sex is unknown and an adult whose sex and age have not been determined.

The remains are scattered about the chamber, possibly due to disturbances by grave robbers and earthquakes. This makes it difficult to determine each individual’s relationship to the others. Scientists expect to use DNA analysis and accelerator mass spectrometry, a radiocarbon dating method, to find out more about these people. Another technique, isotopic analysis, may reveal details about each person’s environment and diet.

But even if these analyses solve the mystery of who’s buried in this tomb, the tests will take several years to produce results. Nevertheless, archaeologists are excited by the findings. Their research indicates that there are more tombs to excavate in this area, possibly an entire necropolis.

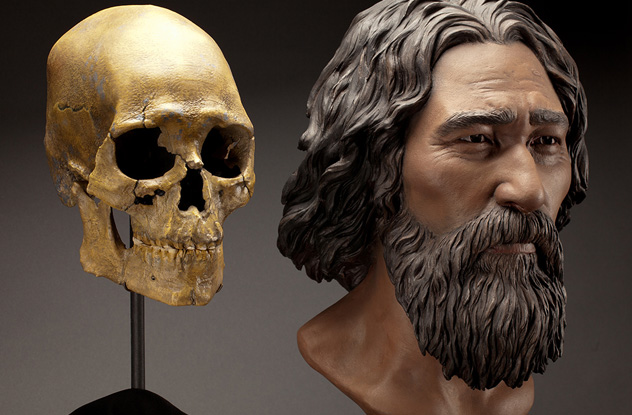

1Kennewick Man

Kennewick Man, the “Ancient One,” is a prehistoric skeleton close to 9,000 years old. It was the subject of a modern lawsuit pitting eight prominent anthropologists and archaeologists against Native American groups and the US government, both of whom wanted to prevent scientific study of the remains.

It all started in the summer of 1996. A couple of college kids were wading along the banks of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, when they discovered a human skull. Almost all of the skeleton was found shortly afterward. But Kennewick Man looked more Caucasian than Native American. The mystery—as well as the controversy—had begun.

The US Army Corps of Engineers took possession of the skeleton because they managed the land where it was discovered. Then, under a 1990 law, some Native American groups claimed the right to rebury the remains in a secret grave. The scientists sued, knowing that if the skeleton were reburied, its secrets would be lost forever.

In 2004, a federal appeals court decided Kennewick Man was too old to establish a definite relationship to existing Native Americans. As a result, scientists could examine the remains. They found that Kennewick Man was about 40 when he died. At 175 centimeters (5’7″) and about 75 kilograms (160 lb), he was incredibly strong but had many injuries and apparently no time to let them heal. An outdoorsman, he was always on the move.

To some anthropologists like Kenneth Owsley, Kennewick Man’s prominent forehead and narrow brain case is like that of the early residents of Japan and Southeast Asia. He believes they used boats to follow the coastline along the Pacific and come to America. Later travelers became the Native Americans we know today, who more closely resemble northeast Asians and probably walked across the Bering land bridge into North America.

But Owsley’s view is challenged by recent preliminary DNA evidence that shows Kennewick Man has Native American genes. A more detailed analysis has yet to be completed, so it’s unclear what the final DNA results will reveal. However, the remains of a young girl who died in a cavern in Mexico at least 12,000 years ago look much like Kennewick Man but have been linked by DNA to modern Native Americans. The battle between anthropologists who want to study Kennewick Man and Native Americans who want to rebury him may not be over.