Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff  Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Warning Labels That Exist Because Someone Actually Tried It

Health

Health Ten Confounding New Inventions from the World of Biomedicine

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

10 Horrific Episodes From One Of History’s Bloodiest Revolutions

From the storming of the Bastille in 1789 to Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup in 1799, the French Revolution shook both France and the world. French revolutionaries and frantic masses shocked the kings and nobility of Europe when they overthrew King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette to establish a republic. In 1793, the king was executed. The queen followed him less than a year later.

Meanwhile, a “Reign of Terror” raged on in an attempt by the revolutionaries to weed out their enemies—chiefly the aristocracy, clergy, and moderates. Tens of thousands of people were killed in the carnage and purges. Millions more perished in wars ignited by the revolution. While many victories were secured, they came at the cost of even more tragedies, sparking debate over the revolution’s legacy that persists to this day.

10 The Attempted Suicide Of Nicolas Chamfort

Nicolas Chamfort was one of the most popular French playwrights of the late 18th century. Several of his quotes, such as “War to the chateaux, peace to the cottages,” became well-known maxims of the time. With two different birth certificates on record for Chamfort, the circumstances of his birth are unclear. The first certificate lists a poor grocer named Nicolas Francois and his wife, Therese Croizet, as his parents. The second one lists his parents as unknown, suggesting he might have been adopted.

Despite his humble origins, Chamfort was a brilliant, witty student who attended school under a scholarship. After graduation, he became a teacher and writer. His plays soon won him wealthy patrons and acclaim from the Academie Francaise. Eventually, he became the secretary of the king’s sister.

However, once the revolution erupted, Chamfort joined the Jacobin Club as their secretary. He also wrote pro-revolutionary newspaper articles and political pamphlets. By 1793, disgusted by the violence of the radicals, he left for the moderate faction. His sharp criticism of his old friends led to his imprisonment for a couple of days.

Fearing he would soon be arrested again, he decided to commit suicide. In September of that year, he locked himself in his study and shot himself in the face, firing off his jaw and nose. Unfortunately, he survived the shot. He then grabbed a paper knife and frantically slashed at his throat and torso. But he survived this, too. One of his servants eventually discovered him, but Chamfort only lived for six more months, all of it in excruciating pain.

9 The Lynching Of Joseph Foullon de Doue

In 1789, Joseph-Francois Foullon de Doue replaced Jacques Necker as the government’s Controller-General of Finances. Necker was greatly respected and loved by the common people, but he angered King Louis XVI and was dismissed from his post.

In contrast, Foullon was cold and despised, believed to be a shill of the aristocracy. With no sympathy for the struggling peasantry, he certainly didn’t gain any popularity when it was rumored that he said, “If they have no bread, then let them eat hay.” However, there’s no evidence he actually said it.

Necker’s dismissal was one of the catalysts for the storming of the Bastille on July 14 of that year. A terrified Foullon, already accused of manipulating the food supply, fled Paris and hid out in Viry-Chatillon. Despite spreading rumors that he died and even giving himself a fake funeral, Foullon was discovered in his hideaway. He was seized by a mob that tied his body with ropes, placed a garland of thistles around his neck, forced him to drink vinegar, and marched him to the Hotel de Ville. There, he was to stand trial by the authorities.

However, the mob took justice into their own hands. After stuffing his mouth with hay and grass, they unsuccessfully tried to hang him twice, with the rope breaking on each attempt. Finally, the rope worked on the third try, and Foullon died. His head was then paraded around on a pike.

8 The Lynching Of Berthier de Sauvigny

Berthier de Sauvigny, a Paris administrator, was the son-in-law of Joseph Foullon de Doue. As fate would have it, de Sauvigny was being escorted to trial when he and the soldier accompanying him suddenly encountered the delighted mob that had hanged Foullon. The mob followed them to the Hotel de Ville, where they were met by the mayor of Paris.

While the mayor and de Sauvigny were talking, the mob demanded that de Sauvigny be taken to the lampposts, where they intended to hang him like his father-in-law. As the frenzied crowd forced their way into the building, the mayor handed the prisoner over to his guards for safe transport elsewhere.

Before they left, however, the mob seized de Sauvigny and carried him to the same place where Foullon had been hanged. Trying anxiously to defend himself, de Sauvigny snatched a musket from a member of the crowd and swung it at his attackers. But his frantic effort was in vain. He suffered bayonet wounds all over. Even worse, one of the soldiers slashed open his chest and flung his heart out. Then de Sauvigny’s head was torn off like that of his father-in-law.

While some crowd members carried the severed heads on pikes, others in the angry mob dragged the headless bodies through the streets. The soldier who had torn out de Sauvigny’s heart later showed it to the mayor at the Hotel de Ville. But the soldier’s triumph didn’t last long. He was killed that same night by a fellow soldier who was disgruntled by the murder.

7 The October March

On October 1, 1789, while much of Paris was starving due to the scarcity of bread and a poor harvest, the king’s guards threw a sumptuous banquet for the royal family in Versailles. The hungry Paris populace was outraged by news of the banquet as well as rumors that the revolutionary flag had been trampled.

On the morning of October 5, a crowd of over 4,000 women and several hundred men declared that they would bring the king and queen back to Paris and return with some bread as well. A wave of them arrived that afternoon. By the next morning, some had gotten into the palace’s courtyard. A royal soldier shot at one of the men, killing him and provoking the crowd into a wild rush.

The crowd swarmed over the palace, planning to capture the queen and kill any guards on the way. After two bodyguards were decapitated by a small man with an axe, a group marched around with the severed heads on poles. One of the heads was carried by a child.

The royal couple and some bodyguards soon appeared on the balcony. King Louis XVI (pictured above) promised to return to Paris as long as the bodyguards were spared. Led by the mob with poles and followed by some stolen carts of flour, the royal family was returned to the capital after over a century at Versailles.

6 The Murder Of The Princesse de Lamballe

In 1749, Marie Therese Louise de Savoie-Carignan was born in Turin, which was ruled by the House of Savoy at that time. At 17, she married the Prince de Lamballe, a powerful relative of the French royal family. The prince died only a year later, and a sympathetic Marie Antoinette invited the young widow to stay at Versailles.

The Princesse de Lamballe became one of the queen’s closest friends and was appointed to Superintendent of the Queen’s Household. Liberal and charitable, the princess also became Grand Mistress in the Freemason lodges for women. However, due to her free spirit and closeness with the queen, Princesse de Lamballe was accused in pamphlets and journals of being one of the queen’s lesbian lovers.

In June 1791, as the French royal family unsuccessfully tried to flee the country, Princesse de Lamballe escaped to England. Hearing of the family’s troubles, she returned to France and reunited with them. In August 1792, they were all arrested, with Marie Antoinette being imprisoned in the Temple and the princess in La Force.

A month later, Princesse de Lamballe was dragged from her cell by an angry mob that demanded she repudiate her loyalty to the queen. When she refused, the mob seized her, beating her to death and mutilating her body. Then they decapitated her, placing her head on a pike and marching it all the way to the windows of the Temple for the queen to see. According to a servant of King Louis XVI, the crowd laughed and shouted for the queen to kiss her old friend’s lips.

5 The Execution Of Guillaume-Chretien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes

Guillaume-Chretien de Lamoignon de Malesherbes, the great-grandfather of acclaimed historian and political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville, was an aristocratic lawyer and administrator who worked to reform the French autocratic monarchy under its two last kings.

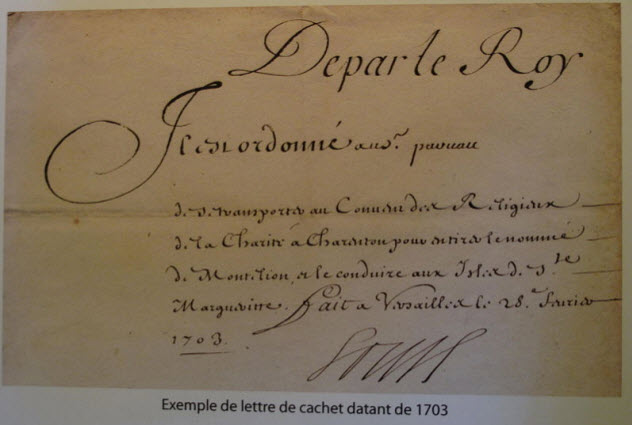

In 1750, Malesherbes became the director of the press, the official in charge of censoring and approving published material. Friendly to Enlightenment writers, he permitted the first editions of Denis Diderot’s massively influential and controversial Encyclopedie, an encyclopedia by various Enlightenment writers critical of the Church and king, to be published.

In 1775–1776, he served as the secretary of state under the new King Louis XVI, reforming the prison system and preventing the misuse of lettres de cachet, royal orders to imprison people without trial. Unable to convince the king to support his reforms, Malesherbes resigned from his post. He spent the next 13 years fighting for legal rights for French Protestants.

When the revolutionaries put King Louis XVI on trial in December 1792, Malesherbes joined the legal team that defended him. The king was executed the next month. Later that year, Malesherbes and his family were also arrested, accused of being counterrevolutionaries. Before going to the guillotine himself, Malesherbes was forced to watch his daughter and grandchildren die first.

4 The Murder Of Anne Durif

In prerevolutionary France where Catholicism was the official religion, the Catholic Church was powerful and wealthy. In addition to owning 6 percent of the country’s land, the Church was granted a number of privileges, including permission to collect an agricultural tithe. The French Enlightenment heavily criticized the Church, especially its priests and clerics whom they saw as corrupt, intolerant, and useless.

Sharing this contempt, the French revolutionaries confiscated and nationalized all of the Church’s property. Naturally, the clergy wasn’t enthusiastic about this. During some of the Revolution’s more violent phases, many nuns and priests were arrested, tortured, and even killed.

In June 1797, authorities were called to the house of Etienne Chabozi after reports that his wife, Anne Durif, was dying from a pitchfork wound. Durif was a former nun. Like at least 500 other nuns of the time, she married to escape financial insecurity and the suspicion of revolutionaries. Her decision shocked the authorities of the local church, and they largely shunned her.

A few months earlier, she had attended Easter Mass with her husband but was chased out by the congregation after the priest called her the “Antichrist.” So on the day that Anne fell onto a pitchfork in the barn, Chabozi explained to police that he had been at church alone when it happened.

After further investigation, however, he was shown to be lying. A neighbor had offered to go to church with him the morning of the accident, but Chabozi refused. Others reported hearing him scream and threaten his wife. It also came to light that Durif was pregnant with a child her husband didn’t want. Eventually, authorities determined that Chabozi had stabbed Durif in the vagina with his pitchfork to provoke an abortion. The child was stillborn, with Chabozi’s assault also killing Durif a few days later.

Chabozi was arrested and guillotined. The crime caused a scandal in the press, with revolutionary papers accusing Chabozi’s priest and the Church’s social stigma against his wife of inspiring him to murder her. Despite the official investigation ruling out this interpretation, the papers only added fuel to antichurch sentiment and violence that year.

3 The Nantes Drownings

During the Reign of Terror, the Republican official Jean-Baptiste Carrier ordered thousands of alleged royalist sympathizers in Nantes, France, to be drowned in the Loire River. Carrier showed no mercy on his many victims. Even pregnant women, children, and elderly people were killed. Supposedly, one woman looked at him through her window and was shot for it.

Some of the victims, young men and women, were allegedly stripped naked, tied together, battered on their heads with musket ends, and tossed into the river in a ceremony called a “Republican marriage.”

In one incident, a group of soldiers carrying cords arrived at the Bouffay jail to fetch 155 prisoners for transfer to a fortress on Belle Isle. However, the soldiers got drunk, only tying up and leaving with 129 prisoners. When a superior ordered them to meet their quota, the soldiers seized people who weren’t even on the list. Instead of being transferred, the prisoners were drowned.

In another incident, a group of prisoners begging to be saved had their limbs cut off, then were placed on a boat that sank and drowned them all.

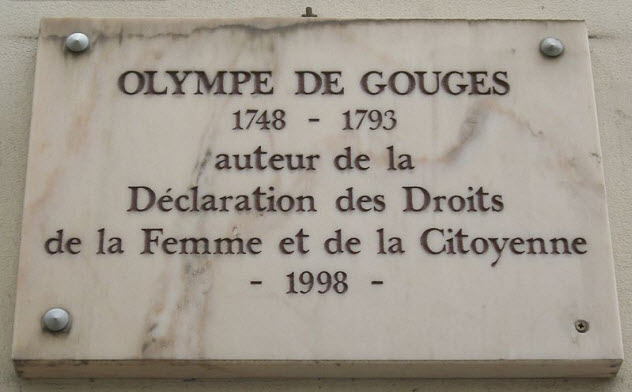

2 The Execution Of Olympe de Gouges

A revolutionary playwright and political activist, Olympe de Gouges is still remembered today for her anti-slavery play, The Slavery of Blacks, and her feminist pamphlet, Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen. Born in 1748 as Marie Gouze, she married at age 16 and had a son before her husband died shortly afterward. She then changed her name and moved to Paris, where she took up a number of social and political causes concerning women and children.

In 1789, the National Assembly passed its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which outlined the rights of citizenship in the new republic. However, not every member of the population was included in the document, particularly women.

Two years later, de Gouges challenged this in her famous pamphlet, asserting that women were equal partners to men and should have the same legal and social rights. While she did support the revolution, she was allied with the moderate Girondins rather than the radical Jacobins. She also liked King Louis XVI and was horrified by his execution.

After the Girondins fell from power, de Gouges was no longer free to criticize the government. She was arrested and guillotined on November 4, 1793. A contemporary report of her death commented that she “mistook her delirium for an inspiration of nature.”

1 The Martyrs Of Compiegne

In September 1792, a group of Carmelite nuns were forced to leave their convent as part of a wave of anti-Catholic measures that shut down churches and banished clergy members who refused to take a loyalty oath to the new republic. Dressed in secular clothes, the nuns stayed in the area for two years, continuing their daily prayers and religious duties.

In July 1794, during the final days of the Reign of Terror, 16 of the nuns were arrested and transferred to Paris. They were imprisoned in the Conciergerie, accused of being counterrevolutionaries plotting conspiracy and treason. The nuns were given no lawyers or witnesses at their trial, and the judges quickly declared them guilty.

On July 17, the nuns were loaded into a cart and taken to the guillotine. The customary mob that descended on these occasions was silent, stupefied by the calm bravery of the nuns. Once the nuns arrived, they burst into a powerful hymn, which lasted until the last sister was beheaded. Their remains were dumped into a mass grave, and the Reign of Terror ended 10 days later.

Since their tragic deaths, their story has been much admired. Pope St. Pius X beatified them in 1906, and a popular opera about them, The Dialogues of the Carmelites, premiered in 1956.

In addition to literature and bizarre mysteries, Tristan Shaw has had a grisly fascination with the French Revolution ever since he read a rather tame picture book about it in the 3rd grade.

![10 Episodes That Were Banned From Television [Videos—Seizure Warning] 10 Episodes That Were Banned From Television [Videos—Seizure Warning]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/image-150x150.jpg)