Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

10 Mythological Perspectives On Menstruation

In many world cultures, menstruation has traditionally been seen as a source of intense female spiritual power, sometimes feared, sometimes revered. Here are 10 views on menstruation from throughout history.

10 Stoneclad

Blood is an important part of the traditional Cherokee belief system, symbolizing life. Beliefs about procreation assert that a baby’s flesh and blood are contributed by the mother, while the father’s sperm becomes the basis of the skeleton. Menstrual blood was considered particularly powerful, symbolic of female strength, and could be channeled against an enemy in sorcery, warfare, and ball-game rituals.

A Cherokee legend tells of a cannibalistic monster named Nun’yunu’wi, or Stoneclad. He was virtually invulnerable to attack due to his stone-like skin, and no warrior could ever hope to defeat him. He would lurk in the mountains, with a magical stick guiding him like a dog, where he would track, kill, and eat hapless hunters whom he stumbled across. His one weakness was that he could not bear to look at a menstruating woman. Though no Cherokee warrior could defeat him, he was destroyed in an encounter with seven menstruating virgins. One by one, they stood in his path and sapped his strength, and he crumbled into dust.

9 Kung Menarcheal Rite

The Kung people of southern Africa believe that menstrual blood is a powerful life force, and a girl’s first menstruation is believed to contain powerful num, or spiritual energy. When a girl first menstruates, she must go through the menarcheal rite, which involves isolation from others and avoiding certain activities. When a girl becomes aware of her first menstruation, she must crouch low with her eyes downcast until a woman mentor assists her. This mentor is not her mother, as the spiritual energy of first menstruation and childbirth are dangerous to combine.

A seclusion shelter is built for the girl, close to but separated from the community. As her spiritual energy is dangerously high, she must avoid affecting the environment. If the girl looks at the Sun, it would become hotter and destroy Earth plants; if she looks at the clouds, they would give no rain. She must be protected from touching the ground or rainwater. Also, she must be kept away from hunting men, as her powerful energy would reduce the power of their weapons and poison arrows and make the hunters lazy and lethargic.

8 Beheading The Red Dragon

In ancient Taoist thought, menstrual blood is called chilong, or Red Dragon, and is the source of female energy. (Semen, meanwhile, is the source of male energy and is called White Tiger.) Women lose their qi energy through menstruation as men lose it through ejaculation. In alchemical gynecology, there were techniques to reduce a woman’s menses to a yellow flow before disappearing altogether, allowing women to maintain their energy.

An ancient story tells of a young woman called Perfected Guan who fled into the mountains to escape an arranged marriage. There, she met an old man with thick eyebrows and blue eyes who drew a line on her stomach and said, “I have beheaded the red dragon for you. Now you can join the Dao.”

The methods were known as “transmuting blood and returning it to whiteness” and “refining the form of the Great Yin.” Preventing menses required sexual purity, allowing women to “behead the Red Dragon.” It was also meant to have the side effect of causing the breasts to retract. Taoist gynecologists recommended cultivating inner concentration and controlled stimulation of sexual energy through massaging the breasts.

7 Tapu

In Maori beliefs, tapu is the most important personal spiritual attribute, said to derive from the gods. It is both intensely personal and a universal force. Blood is said to be extremely tapu, and thus so are menstruating women. Therefore, this spiritual power means that restrictions of safety had to be placed on them. Menstruating women were not allowed to enter the sea, as sharks can smell the blood, nor were they allowed to ride horses, which can also smell blood.

Some claimed that menstruation was linked to the Moon, said to be the husband of all women, and that menstrual discharge was so tapu because it was considered as a kind of immature or undeveloped human being. Chiefs and other men of rank were said to avoid women, as contact with places polluted by menstrual power could rob them of clairvoyant power. Some have claimed that menstrual blood was considered “unclean,” but others have said that this is a misconception based on the conflation of Maori mythological concepts with Christian ideas.

In 2010, Te Papa Museum in Wellington, New Zealand, caused controversy when an installation of Maori jade artworks included a warning for “wahine (women) who are either hapu (pregnant) or mate wahine (menstruating)” to stay away, as the tapu of the objects and the tapu of menstruating women would be dangerous to put together.

6 Lady Blood

The Maya believe that menstruation and childbirth were linked to the Moon Goddess, sometimes known as Lady Blood or Ixchel. The Quiche Maya referred to menstruation as “the blood that stems from the moon,” while the Itzaj Maya say “her moon is lowered” when a woman menstruates. The Tzotzil believed that the Moon itself was menstruating during the new moon.

Menstrual blood was considered a source of gendered power. Penile blood was the equivalent for men and was released in ritual ceremonies involving needles to allow them to be closer to the gods. In the case of women, it was seen as largely out of their control. One word for menstruation, yilic, derived from the word ilah or ilmah, translated as both “to menstruate” and “to see.” Menstruation was seen as a form of sight, emanating not from the eyes but from the womb and the blood. Another Maya word for menstruation, u, also referred to the Moon and a month in the lunar calendar.

5 Jewish Male Menstruation

A very weird element of medieval anti-Semitism was the notion that Jewish men menstruated. It can be traced back to Augustinus in the fifth century, who believed that Jewish men suffered “the women’s disease.” The myth was inspired as much by the notion of women as impure and diseased as it was by hatred of Jews. The supposed loss of blood through menstruation was said to drive Jewish men to seek out the blood of Christian babies to compensate. This is the origin of the blood libel myth that plagued Europe for centuries.

Later thinkers revised the idea, instead believing that Jewish men suffered from monthly bouts of rectal bleeding, to the extent that suffering from hemorrhoids could be used as evidence in an Inquisition trial of someone suspected of being secretly Jewish. According to Jewish historian Yusef Yurashalmi, Juan de Quinones de Benavente composed an entire treatise in the 17th century trying to prove the idea, implying that, “Jewish males . . . are, in effect, no longer men but women, and the crime of deicide has been punished with castration.”

4 Geh

The ancient Zoroastrians associated menstruation with the evil god Ahriman. After the good god Ohrmazd, or Ahura Mazda, created the universe, Ahriman immediately attacked it, only to be knocked out for 3,000 years when Ohrmazd recited a sacred prayer. Various demons worked to bring their evil lord out of his stupor, which was finally accomplished by Geh (or Jeh or Jahi), the whore demoness, who promised to bring affliction and pestilence onto righteous men, oxen, and the entire pure world. Her words revived Ahriman, who kissed her on the forehead, and she became the first to be “polluted” by the blood of menstruation, supposedly created to make humans unable to fight against the forces of evil.

Another version of the myth has Geh becoming Ahriman’s chief “whore demon,” meant to defile women, who will in turn defile men so they turn away from their proper work. Modern Zoroastrians consider menstrual blood to be nasu, or dead, decaying, polluting materials. Zoroastrian taboos insist upon strict separation of menstruating women: No one may approach within 1 meter (3 ft) of her, she must be handed food on metal plates, and she must avoid meat or invigorating food that may strengthen “the fiend of pollution.”

3 Pliny The Elder

First-century Roman author Pliny the Elder is responsible for a great number of menstruation myths that persisted in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. In his Natural History, Pliny wrote of the destructive power of menstrual blood, which he believed could wither fruit and crops, sour wine, dull mirrors, rust iron and bronze, blunt razors, kill bees, pollute purple fabrics, drive dogs insane, drive off storms and whirlwinds, and cause miscarriage in humans and horses. Having sex with a menstruating woman during a solar or lunar eclipse, he claimed, could lead to disease or death for the male partner. Menstrual blood did have some curative properties, though, curing gout, scrofula, skin growths, erysipelas, fevers, and bites from rabid dogs. It also served as protection against dark magical arts from the East.

After his exhaustive list of menstrual blood properties, Pliny luridly claimed: “This is all it would be right for me to report and most of that I do not say without shame. That which is left is detestable and unspeakable, and so my work should hasten from the subject of man.” Pliny’s opinion on the whole matter can best be encapsulated by this passage: “Hardly can there be found a thing more monstrous than is that flux and course of theirs.” This would all be frankly laughable if Pliny’s beliefs hadn’t stayed around for over a millennium before being questioned.

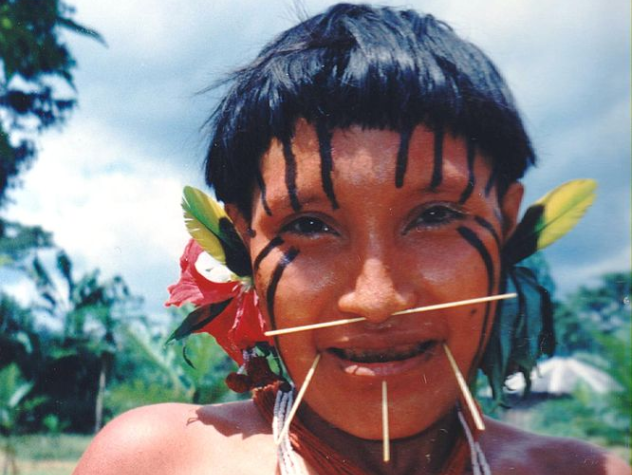

2 Yanomami Seclusion

For the Yanomami people of northern Brazil, blood is a symbol of cosmic entropy. Menstruating women and killers who have ingested enemy blood are both known as unokai, which can be translated in the former case as “the state of homicide of women.” Both warriors and pubescent girls are considered to have an excess of blood in their bodies and must be isolated and secluded with ritual in order to maintain safety.

On her first menstruation, a girl must inform her mother, who builds a seclusion hut using leaves from a particular shrub in order to hide the girl from the eyes of men. This is justified by an ancient legend telling of a young girl who was secluded on her first period while the community prepared a ritual feast for visiting guests. After hearing a man shouting, “Every woman without exception must sing and dance,” she assumed it was meant for her and emerged from seclusion to join in. The ground immediately turned to mud, and the entire village sank into the underworld and became rocks.

To prevent such an outcome, a girl on her first menstruation is subject to a number of ritual obligations: She must be naked, avoid direct contact with water by drinking with a hollow cane pushed deep into her mouth, may speak only in a whisper, and is limited to a diet of plantains and the occasional crab shell. If she does not properly complete her seclusion, it is believed that she will prematurely age and become an old woman.

1 Kamakhya

In Sakta Tantra, the menstrual cycle in the female body represents the changing seasons and universal order. It is particularly associated with the goddess Kamakhya, or Mother Shakti, whose Kamarupa temple is located in Gauhati, in India’s Assam state. At the annual, three-day Ambubachi Mela festival in August or September, the goddess’s yoni (vagina or womb) is believed to manifest itself on Earth, attracting tens of thousands of devotees every year. At the Kamarupa temple, a stone of red arsenic, said to be the yoni of the dismembered goddess Sati, flows with red water during this time. The temple is closed for three days as orthodox rituals are carried out inside. On the fourth day, the doors are opened, and devotees are allowed to receive darsan (blessing via viewing the goddess through red cloth), prasad (blessed food), and maybe a piece of red cloth from her sari, representing fecundity.

In tantric alchemy, the goddess’s uterine blood is associated with red arsenic, and it is believed to have healing powers, particularly curing people suffering from leucodermia, as well as the ability to transmute metals into gold. Some extremist Tantrics believe that the Ambubachi festival is the best time of year to commit human sacrifices, which are generally frowned upon these days. One mystic even tried to sacrifice his 18-month-old daughter at the temple, slicing at her neck with a razor before temple officials intervened, and the man was arrested.

David Tormsen’s pubescent ignorance spawned even wilder notions than these, but he must never speak of them. Email him at [email protected].