Creepy

Creepy  Creepy

Creepy  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Creepy

Creepy 10 Death Superstitions That Will Give You the Creeps

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movies That Get Elite Jobs Right, According to Experts

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Times Real Laws Were Based on Bizarre Hypotheticals

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 Inspiring Tales of Horses Being Human

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

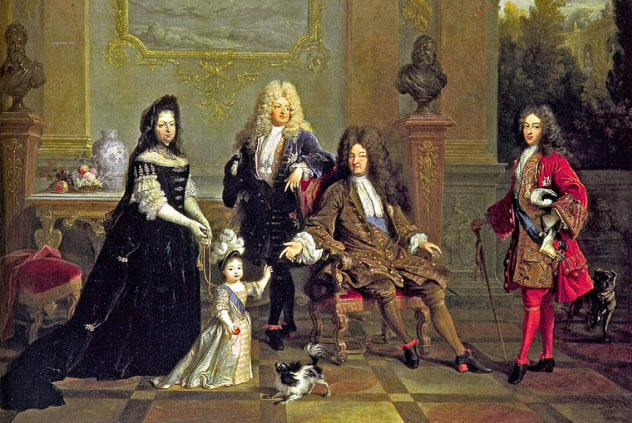

10 Surprising Glimpses Into Louis XIV’s Royal Court

King Louis XIV of France is the longest-reigning monarch in European history (1643–1715). His absolutism and ambition to make France the dominant power on the Continent were the hallmarks of the age. As the “Sun King,” his desire to have everything revolve around him began at home in his glittering court at Versailles. The magnificent palace became the seat of government in 1682, a “gilded cage” where the king kept his nobles on a tight leash.

While the rest of the world saw the pomp and splendor of a great empire, the inner life of the court betrayed the intrigues, decadence, and jealousies that hounded an all-too-human king. For the most part, we are indebted to the Duc de Saint-Simon’s memoirs for this inside access into Louis XIV’s court.

10 Court Etiquette

The game of currying the Sun King’s favor was played out in Versailles for all it was worth. Depending on the occasion, from 3,000 to 10,000 people crowded the palace. Nobles were regulars, seeking rewards like pensions in return for their constant service. Many had their own living quarters in the Versailles outbuildings and were obliged to adhere to the maddeningly intricate etiquette that governed daily life at the royal residence.

Ranked immediately below the royal bastards, the hierarchy of nobles from duke to baron was strictly delineated at court. Everyone knew who was superior to whom through the use of a codified system of gestures and language. Rank determined who sat down or stood up in the presence of the king and who could use an armchair, a chair with a back, or a stool. There were rules on who could approach a superior and where and when this was appropriate.

Seemingly trivial actions were covered by etiquette. For instance, knocking on the king’s door was forbidden. One had to scratch lightly at the door with the pinkie finger in order to be let in. When sitting down, a gentleman had to slide his left foot in front of the right, place his hands on the sides of the chair, and gently lower himself down. A lady could not hold hands or link arms with a gentleman. Instead, the gentleman had to bend his arm and allow the lady to place her hand on it.

The Versailles dress code was probably of the most consequence to nobles. Courtiers were compelled to keep up with the latest fashions in imitation of the king. Each formal event required a different set of expensive attire. Furthermore, Louis was constantly changing or adding accessories to the royal wardrobe, and courtiers had to follow suit if they wanted to remain in favor.

The expense sent some nobles into debt. It is even argued that this was Louis’s real intent—to bankrupt his nobles in order to better manipulate them and concentrate the power for himself. Fashion was an integral part of acquiring and maintaining influence. This was reflected in the two fairy tales written around this time, “Cinderella” and “Puss in Boots,” which accentuate fashion as a means of gaining respect and privilege.

9 A Day In The Life

Life in Versailles was conducted with military-like precision, all revolving around the king’s activities. The Duc de Saint-Simon wrote of Louis XIV: “With an almanac and a watch, you could be three hundred leagues from here and say what he was doing.” The king’s day, from awaking to retiring, was regulated like clockwork and accompanied by pomp and ceremony. Courtiers who were expected to participate had to plan their work schedules accordingly.

The king’s day began at 7:30 AM when a few favorites entered the bedchamber for the grandes entrees (meaning “those with the right to talk to him first in the morning”) when Louis was washed, combed, and shaved. After Louis had recited the Office of the Holy Ghost, the second entree (meaning “a group of nobles”) was admitted to watch him dress and eat breakfast. Then it was off to mass at 10:00 AM, where the rest of the court accompanied the king as he traversed the Hall of Mirrors to the chapel. Every day, a newly composed hymn was sung by the choir.

At 11:00 AM, council meetings were held at the king’s apartments, followed by a private meal in the bedchamber at 1:00 PM. At 2:00 PM, Louis announced his intentions for the afternoon, perhaps a promenade, a picnic with the ladies, or a hunt. In his later years, Louis needed the fresh air to quell his headaches, which were brought about by overexposure to perfume.

By 6:00 PM, Louis was ready to sign letters and study state documents prepared by his secretaries. Supper was au grand couvert (meaning “a large meal”) at 10:00 PM, after which Louis spent some time with his family. At 11:30 PM, a shortened version of the morning ceremonials attended the king’s retiring.

8 A Filthy Royal?

The Sun King’s personal hygiene is a matter of debate among historians. On the one extreme is the rumor that Louis took only three baths in his life. It is quite clear how the rumor started: People in 17th-century Europe were told that bathing opened the body’s pores to disease. Bathing was considered to be a terrible health hazard. Instead, people doused themselves with perfume to mask the inevitable stench.

They also observed the ring of dirt around the cuffs and collars of their linen shirts and concluded that the flax in the linen had the magnetic ability to draw out dirt and perspiration from the body. Therefore, changing one’s linen shirt often was the path to cleanliness in lieu of a bath.

Louis was not immune to these bizarre notions. The modern nose would have turned away from his smell. Louis also had bad breath, which prompted his mistress, Francoise-Athenais de Rochechouart de Mortemart, marquise de Montespan, to lace herself with a prodigious amount of perfume to overwhelm the king’s halitosis. But that triggered Louis’s headaches. They had a flaming row in the royal coach about how bad they smelled to each other.

The belief that the king bathed only three times in his life is rather implausible. Louis did take care to keep himself clean, just not in the way we moderns go about it. Due to his perfume-induced migraines, he was rubbed instead with spirits or alcohol to disinfect his skin. The king changed his underwear three times a day. He even had an entire apartment in Versailles turned into bathrooms, with two private baths for himself. Though Louis was understandably reluctant to bathe, and then only upon his doctor’s orders, these baths must surely have been used more than three times. The Sun King wasn’t the filthy royal he was made out to be.

7 Supper With The Sun King

Louis took his breakfast and midday dinner in private. But the 10:00 PM supper was an opulent affair open to the entire court. Five hundred people were needed to cook and serve this meal.

At the appointed hour, courtiers and attendants would crowd into the antechamber of the royal apartments. The dress code required the men to carry swords. The king sat at the center of the long side of a rectangular table. Guests sat along the shorter sides (no crossing of the legs, please) with the remaining side open for servers. Musicians played on a platform in front of the king.

All of Europe took its cue from the formal customs of dining developed at Versailles. Le service a la Francaise (“service in the French style”) was considered the only civilized manner of dining. After a priest said grace, bowls of scented water were passed around for guests to wash their hands in. Food was served in a succession of “services”: hors d’oeuvres, soups, main dishes, go-betweens, and fruit.

Within each service (except for the fruit course), there were between two and eight dishes. Diners had to bow to the food as it came in. Officers of the household served the dishes on plates of gold for the king and silver for the princes, set down on the table at prescribed locations. Diners took food that was near at hand without moving the plates and passed along dishes that were beyond reach. Drinking glasses were handed out only upon a softly spoken request. Guests were not allowed to converse because that would distract Louis from his meal.

In 1669, Louis banned all pointed knives from the dinner table. Before then, they had been used as toothpicks or even as murder weapons in dinner brawls. Though the fork was already in common use, Louis still preferred to eat with his fingers.

With such a large and extravagant meal, guests could only sample a small portion of the menu. Nevertheless, Louis had eaten 20 to 30 dishes by the time he was ready to go to bed at 11:30 PM, pocketing the candied fruit and nibbling on a boiled egg as he entered his bedchamber. It is not surprising that when Louis died in 1715, doctors who autopsied his body noted that his stomach was three times the average size.

6 The Fish That Caused A Suicide

Preparing the opulent banquets for the king and his court must have been an extremely stressful job. No wonder Francois Vatel, the “Prince of Cooks,” cracked under the strain.

In April 1671, King Louis announced his plan to visit Louis II de Bourbon, the Prince de Conde, and stay for three days at his chateau in Chantilly. This was more of a punishment than an honor for the prince. At this time, before he kept the aristocracy in his “gilded cage” of Versailles, the king had to drag his courtiers with him wherever he went in order to keep a watchful eye on the nobles. Louis started off for Chantilly with 600 aristocrats and thousands of hangers-on.

Vatel was not actually a chef. Instead, he was a maitre d’hotel (his office was called a “bouche”), responsible for the organization of such grand receptions, including entertainment like fireworks and stage shows. Vatel and the prince had only 15 days to prepare for the king’s visit. Without modern transportation, all food had to be sourced locally. As an officier de la bouche, Vatel was expected to accurately estimate how much was needed to feed the host now descending upon Chantilly.

On the first night, a feast was held in the forest. The turnout of 5,000 was unexpected, and the roast fell short by two tables. Moreover, overcast skies put a damper on the fireworks show, which had cost 16,000 francs. Vatel spent the next hours tormenting himself for the fiasco, despite assurances from the prince that everything was fine. “My honor is lost; this is a humiliation that I cannot endure,” Vatel lamented. But there was still the next day to consider.

Vatel had scoured all the seaport towns in the area for fish and spent a sleepless night waiting for his orders to arrive. At 4:00 AM, a lone purveyor appeared with two loads of fish. “Is this all?” cried Vatel. The man replied, “Yes, sir.” A despairing Vatel waited a bit longer. No fish arrived. It finally unhinged Vatel.

Going up to his room, Vatel took his sword and impaled himself through the heart. Had he waited a little longer, he would have spared his own life. Shortly after killing himself, the rest of the fish, delayed on the road, were delivered to Chantilly.

5 The Enema Fanatic

Besides his bathing habits, another thing about Louis XIV where it is hard to separate fact from fiction is his reported addiction to enemas. Shooting liquid up the anus to cleanse the colon has a long history of health benefits. The king became such a fan that he supposedly had over 2,000 enemas in his life. Some attribute his longevity to the procedure.

Other historians think 2,000 is too high a number. The king had a bleeding and an enema (called a lavement) once a month prescribed by physicians. But other stories have Louis taking off every night after dinner for a rectal cleanse. Eventually, he became so fond of it that he would have an enema while holding court.

In a polite society where imitating the king was fashionable, aristocrats scrambled for their own clyster syringes and had sessions three or four times a day. Servants usually administered the enema, but bent clyster syringes also appeared to allow self-administration. The Duc de Saint-Simon related that the Duchesse de Bourgogne once threw modesty to the winds and had a maid crawl beneath her gown to give her an enema while she chatted with the king in the midst of a crowded party. For such public enemas, special clyster syringes had been developed with attachments that covered the buttocks.

Even taking into account the exaggerations in such tales, there is no doubt that Louis was the “Enema King” of his day and that the court shared his mania. We still have surviving satirical buttons from the period depicting the Sun King taking an enema.

4 The Fall Of Nicolas Fouquet

The richest man in France, the ambitious Nicolas Fouquet made his greatest mistake when he showed off his vast wealth to Louis XIV.

Born in 1615 to a wealthy shipowner and parliamentarian, Fouquet lived by his family motto, Quo non ascendet (“To what heights will he not climb”). He steadily rose through the royal administration to become finance minister under the powerful Cardinal Mazarin, chief minister to the young Louis XIV. In effect, Fouquet was banker to the king, and the office allowed him to enrich himself through dubious means, although they were acceptable at the time.

Fouquet’s chateau, Vaux-le-Vicomte, and its breathtaking gardens were the finest in France. It was the setting for the most lavish fetes the 17th century had ever seen. Such magnificence was not enough for Fouquet. Upon Mazarin’s death in 1622, he aspired to the vacated post of chief minister, but Louis decided to take absolute rule for himself and abolished the post.

Meanwhile, Mazarin’s private secretary, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, saw his chance to seize the office of finance minister from Fouquet and schemed to get rid of him. Colbert revealed to the king the irregularities in Fouquet’s operations. He accused Fouquet of embezzling millions, which were actually pocketed by Mazarin. Confident that the king knew of his loyalty, Fouquet ignored his friends’ warnings of the plot against him.

Louis believed Colbert’s accusations and decided that Fouquet must answer for his crime. But first, he wanted to see for himself the extent of Fouquet’s allegedly ill-gotten wealth and expressed a desire to visit Vaux-le-Vicomte.

An unsuspecting Fouquet enthusiastically welcomed the king on that fateful day of August 17, 1661. Pulling out all the stops to impress the king, Fouquet had prepared an extravagant soiree, with sumptuous food, dazzling fireworks, and theatrical performances. The king had seen enough. The ostentatious display convinced Louis that Fouquet was indeed stealing from his treasury. Louis would have arrested Fouquet on the spot, but the queen mother dissuaded him.

But that evening sealed Fouquet’s fate. He was arrested three weeks later in Nantes. In the “trial of the century,” the judges voted to have Fouquet banished from France. But Louis thought that was too kind. Overruling the judges, he had Fouquet imprisoned for life. Louis seized everything that he could from Vaux-le-Vicomte, even the orange trees, and sent it to Versailles.

Fouquet died in prison in 1680.

3 The Penitent Mistress

In 1661, tongues began to wag in court about how intimate Louis was with his new sister-in-law, the beautiful Henrietta Anne of England, wife of the Duc d’Orleans. Seeking to avert a scandal, royal counselors tried to cover up the liaison by making it appear that the king was really interested in the duchesse’s lady-in-waiting, Louise-Francoise de la Baume Le Blanc de La Valliere.

To make appearances convincing, the royal secretary ghostwrote love letters allegedly exchanged between Louis and La Valliere. Other courtiers staged late-night trysts between the two. It didn’t take long for the pretense to become real: Louis fell in love with the intelligent and cultured La Valliere.

As Louis was now married to Marie-Therese of Austria, La Valliere became the official royal mistress. She eventually bore four children for the king. La Valliere continued her artistic and literary pursuits—attending plays by Racine and Moliere, studying painting, and discussing Aristotle and Descartes. In 1667, Louis made her Duchesse de Vaujours. But the same year also saw the appearance of a rival for the king’s affection, the notorious Madame de Montespan.

La Valliere patiently endured the humiliation of sharing a roof with de Montespan, who had become the king’s de facto mistress. Their apartments were connected, so she couldn’t fail to be aware whenever king and mistress were engaged in amatory activity. Louis had grown cold toward La Valliere. Once, at the prodding of de Montespan, he threw his spaniel, Malice, at La Valliere, saying, “There, Madam, is your companion; that’s all.”

All this time, La Valliere’s conscience was bothered by her adulterous relationship with Louis. Stricken by a serious illness, she had a spiritual crisis. When she recovered, she confessed her sins and became more deeply involved in her Catholicism. La Valliere withdrew from the worldliness of the court and spent her days in prayer and mortification. She wrote a theological work, Reflections on the Mercy of God.

La Valliere’s conversion exposed Louis to the public as a philanderer and a religious hypocrite. In 1674, he finally allowed La Valliere to leave and become a nun at the Carmelite convent in Paris. Her odyssey from adulteress to Sister Louise de la Misericorde was hailed a moral miracle, an indictment of the immorality reigning in Versailles.

2 The Affair Of The Poisons

Voluptous, seductive, haughty, and ambitious, Athenais de Montespan was the polar opposite of Louise de La Valliere. In fact, de Montespan was the most influential woman in Louis XIV’s court and feared by the courtiers.

She was the wife of the Marquis de Montespan and a former lady-in-waiting to Queen Marie-Therese. Charmed by her beauty and wit, Louis took her in as his mistress in 1667. She bore him seven children, six of whom survived and were legitimated. But by 1677, Louis was becoming bored with de Montespan and showed it through a succession of affairs, including one with a former nun.

De Montespan was not above doing something crazy to win the king back, and Louis knew it. He began to receive disturbing reports from Gabriel-Nicholas de La Reynie, a Paris police lieutenant, about a spate of poisonings. La Reynie’s investigations had uncovered the source of the poisons, the witch Madame La Voisin, who had friends in court. It was revealed that de Montespan was a frequent visitor to her home. Court gossips whispered that de Montespan had poisoned her most recent rival, Mademoiselle de Fontanges, and was secretly poisoning the king himself.

Upon interrogation, La Voisin’s daughter accused de Montespan of making a pact with Satan and holding black masses to regain Louis. The renegade priest who allegedly performed the rituals testified that a chalice with a mixture of blood from a bat and a newborn child was offered on an altar over de Montespan’s nude body. The shocked king ordered La Reynie to keep his findings secret.

Though it was true that de Montespan was part of La Voisin’s circle, there is no real evidence to support the accusations of satanism. She cannot be linked to the poisoning of de Fontanges and certainly had no motive to murder Louis. The suspects must have seen her only as a convenient scapegoat. The king himself seemed not to have taken seriously his mistress’s role in this “Affair of the Poisons.” He didn’t allow de Montespan to be interrogated and let her remain in court for several more years. In the end, the affair saw 36 people condemned to death, including La Voisin, who was burned at the stake in 1680.

1 The Secret Wife

Francoise d’Aubigne’s improbable life is a classic rags-to-riches story. The daughter of a career criminal, Francoise’s early years were stormy. After a brief sojourn in Martinique, she lived for a while with an abusive distant relative. Then she endured convent schools in Niort and Paris. Returning to her penniless mother, the 14-year-old Francoise was forced to beg for food.

In 1652, Francoise married the sickly and paralyzed satirist Paul Scarron. She was introduced to her husband’s acquaintances in Parisian literary and philosophical circles. Among these valuable contacts was Athenais de Montespan. After Scarron’s death, Francoise managed to survive through the financial support of her friends. In 1669, she was invited to become governess of the illegitimate children of de Montespan and the king.

Francoise’s teaching skills so impressed the king that he gave her the fief of Maintenon. When Louis and de Montespan broke up, Francoise played a vital role in reconciling Louis with Queen Marie-Therese. Devoted to Francoise, the queen died in Francoise’s arms a year later.

The bereaved king drew closer to Francoise and decided to marry her in 1683. But her lowly social origins necessitated that the marriage be kept secret. It was never announced publicly, and Francoise never assumed the title of queen. To keep the fact hidden, de Montespan was allowed to stay on at the court for another decade. The morganatic union (which is a marriage recognized by the church but not by the state) meant that none of Francoise’s relatives could inherit the throne.

In Versailles, however, Francoise had the duties, if not the title, of queen. Her passion for teaching led her to found Saint-Cyr, a school for girls from poor families. She advised Louis especially on religious issues, such as the appointment of bishops and abbots. Historians even credit her as being a guiding force behind the revocation of the Edict of Nantes and the resumption of persecution of the Huguenots, but such claims are exaggerated. Francoise was herself a former Protestant and was therefore predisposed to tolerance.

From a childhood of poverty to uncrowned Queen of France, Francoise could look back and truthfully say, “My life . . . has been a miracle.”

Larry is a freelance writer whose main interest is history.