History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

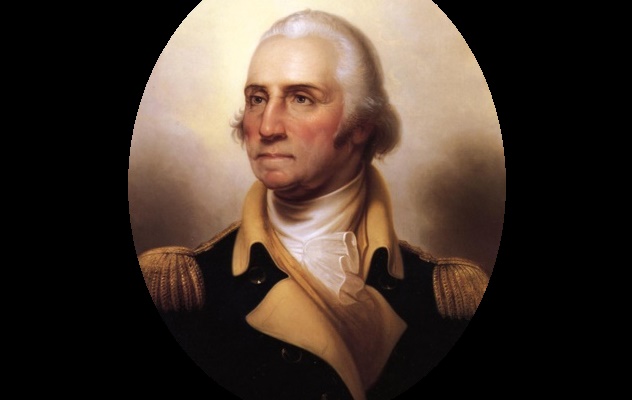

10 Pivotal Missions Of George Washington’s Spies

Anyone who has watched AMC’s Turn: Washington’s Spies is familiar with the Culper Ring, General George Washington’s most successful Revolutionary War spy ring. But the Culper Ring was but one of a number of the general’s spy rings. He even recruited individual spies to work alone. Here are 10 of the most important missions of America’s first spies.

10 The Man Who ‘Could Not Tell A Lie’ Lied

George Washington first mastered the techniques of spying while serving in the British army during the French and Indian War (1754–1763). As an American, Washington was tasked with recruiting white and Native American spies and managing their operations. He also targeted French spies and fed them false information. His commanding officer, General Edward Braddock, used codes and ciphers, and it’s probable that Washington learned and used them as well. The need for good intelligence was driven home when Braddock attacked Fort Duquesne on September 14, 1758, without knowing what enemy forces were nearby. The battle nearly ended in disaster, and Braddock and his command would have been wiped out if not for the intervention of Washington.

When Washington assumed command of the colonial forces in July 1775, they were besieging the British holed up in Boston. But when Washington inventoried his supplies, he was shocked to discover his army had only 36 barrels of gunpowder, about enough for each of his men to fire their gun just nine times. He knew it would be a disaster should the redcoats decide to break out of Boston. Worse, if his own men knew of their dire situation, morale would plummet.

So Washington did what he’d do many times afterward: He fed the British false information. He sent men into his own ranks and into the streets of Boston armed with misinformation, claiming he had 1,800 barrels of powder. The enemy stayed inside Boston, and morale within Washington’s ranks remained high. The man who, according to legend, could not lie to his father after he cut down a cherry tree, proved to be quite adept at lying.

9 The Mercereau Family And The Staten Island Raid

In March 1776, Washington forced the Brits to flee Boston, and in June they landed on Staten Island in preparation for taking New York City. On July 12, Washington held a council of war with his generals to determine if they should attack the head of England’s forces, General William Howe (pictured above), on the island. The generals unanimously voted against the attack. Washington then asked if a smaller raid could be pulled off to “alarm the enemy.” The raid was tentatively approved with General Hugh Mercer given command after he reconnoitered Howe’s troop dispositions.

Mercer had a captain, John Mercereau, in his ranks who had lived on Staten Island until recently. His brother Joshua still lived there. Captain Mercereau slipped onto the island and, with the help of Joshua, discovered that the British did not have one large encampment on the island but had spread their soldiers across the island bivouacked in civilian houses, with some 600–700 redcoats were in houses along the island’s northwestern shoreline.

Mercer proposed to ferry 1,400 men across the Arthur Kill and attack the Brits along the shore on the night of July 17. They would then slip back across before Howe could counterattack. The raid was ultimately canceled due to bad weather and unfavorable tides.

But the Mercereau family’s intelligence was of such superior quality that Washington enlisted the family as a network of spies operating on Staten Island for at least three years. It became America’s first true spy ring. The ring was headed by Joshua’s young son, John, who used his withered arm to disguise himself as a cripple. After John’s courier was captured, John took over courier duties, crossing the Arthur Kill on a raft with his secret communiques stuffed in a weighted bottle and towed behind by a string. If John was stopped mid-river by the British, he would simply let go of the string, allowing the messages to safely sink into oblivion.

The Mercereau Ring became so large by 1777 that Washington assigned it a case officer. The commander in chief trusted the members of the network so much that he even allowed them to help with prisoner exchanges.

8 Knowlton’s Rangers At Harlem Heights

While still in Boston, Washington was introduced to a remarkable man named Thomas Knowlton, a Connecticut captain who, like Washington, was a veteran of the French and Indian War. He was already a Revolutionary War hero, gallantly repulsing a number of British attempts to take the American left flank at Bunker Hill. (In the above painting of the battle at Bunker Hill, Knowlton is at left wearing a white shirt and holding a musket.)

On January 1, 1776, Washington promoted Knowlton to major and gave him command of the 20th Connecticut Continental Infantry tasked with “special” missions. One of their first was to raid the town of Charlestown, Massachusetts, just north of Boston where General Howe was bivouacked on the night of January 8.

That evening, Howe was watching a satirical play entitled The Siege of Boston in which Washington was portrayed as a comic rube. Knowlton’s men slipped into town and burned eight buildings. Knowlton also captured a number of British officers and escaped without a casualty. When a soldier burst into Howe’s theatrical production with news of the raid, the audience thought he was part of the play and roared with laughter.

In late August 1776, General Howe was finally ready to attack New York City from Staten Island. Washington assumed that Howe’s main attack would be on Manhattan, so he split his army in two: half in Manhattan, half on Long Island. But Howe focused solely on Long Island and had part of his army engage Washington’s Continentals at Brooklyn Heights while he sent the rest of his troops behind the defenders.

By the time Washington realized what was happening and sent for the other troops, it was too late. They didn’t reach the battle in time, and it was a disaster that cost Washington some 1,400 men. The disaster would have been greater had Howe pursued the defeated rebels and decimated Washington’s army right away. In a feat with few parallels, Washington managed to ferry 9,000 of his men safely across the East River to Manhattan in just one night.

That same month, Major John Knowlton was promoted to colonel and given an elite command of light infantry known as Knowlton’s Rangers. They were ordered to reconnoiter and determine British movements and locations, an effort to prevent a repeat of the Brooklyn Heights debacle. While Knowlton’s unit was short-lived, it is usually credited as America’s first military intelligence organization.

In September, Washington had drawn most of his army to northern Manhattan to lick their wounds from their humiliating Long Island defeat. By mid-month, Howe, too, had crossed over to Manhattan and charged straight at Washington’s camp at Harlem Heights.

On the morning of September 16, Washington was surprised with news that Howe was nearby. The general sent Knowlton’s Rangers to probe for Howe’s vanguard. The two advance forces ran straight into each other. Instead of retreating and reporting to Washington as they were ordered, the Rangers engaged the enemy.

Howe sent the rest of his army in pursuit, so Washington responded by throwing his troops in as well. The result was a draw with both sides eventually retreating. For the Americans, it was uplifting: After a number of defeats, they had stood toe-to-toe with the greatest army in the world and survived. But their victory was tempered by the news that Knowlton had been shot and killed.

His force would not outlive him for long. Exactly one month later, Knowlton’s Rangers were captured at Fort Washington. Several of the rangers would die in British prisons. Despite their sad demise, Knowlton’s Rangers are considered the precursor to the US Army Rangers, Special Forces, and Delta Force.

7 Nathan Hale’s Mission To New York City

After the debacle on Long Island, Washington was desperate for information as to what Howe planned to do next. Just two days after he’d ferried his men across the East River to Manhattan, he begged his generals to set up a “channel of information . . . to gain intelligence of the enemy’s designs, and intended operations.” When no reliable intelligence was forthcoming, Washington turned to Knowlton’s Rangers. One of the more experienced Rangers, Lieutenant James Sprague was asked to cross back over the East River and reconnoiter Howe’s troops and ascertain where they were headed. His response: “I am willing to go and fight them, but as far as going among them and being taken and hung like a dog, I will not do it.”

Only one Ranger, in fact, volunteered for the mission: Nathan Hale. Hale was a Connecticut teacher and neighbor of Thomas Knowlton who had just joined Knowlton’s Rangers as an officer. It would be his first and only mission.

Despite Hale’s lack of training in espionage, Washington sent him to Long Island disguised as a Dutch teacher. Unfortunately, Hale tried to use his Yale diploma as proof that he was a teacher, a document that had his real name instead of an alias. Worse, Hale was easily memorable to anyone who had met him, his face badly scarred from an accidental gunpowder explosion. Hale was given no money, no contacts with civilians, and was not even trained to use ciphers or codes. Nor was Hale taught to keep his mouth shut about his mission: He spilled the whole thing to a fellow Yale classmate just before he departed.

Not long after he started his mission, the British crossed over to Manhattan, which rendered Hale’s mission unnecessary. But Hale apparently decided to stay and acquire intelligence anyway. He was discovered and apprehended on September 21 with incriminating papers on his person. Sentenced to execution without trial, he was hung the next morning after uttering his famous words: “I regret I have but one life to lose for my country.” As one of the few American spies to be caught and executed in the Revolutionary War, he became a martyr for the cause and a hero to the intelligence community, despite performing only one mission (and a failed one at that).

His death would have a profound effect on Washington. He realized that civilians familiar with the area they were to operate in, like those in the Mercereau family spy ring, were harder for the British to uncover than military spies who walked and talked like soldiers and knew nothing of local customs. From then on, Washington concentrated mostly on local civilian spies.

Some historians have questioned whether Hale uttered the final words attributed to him, but at least two eyewitnesses claim that his last words were touching and brave. Hale was, as a Yale graduate, probably familiar with and capable of borrowing a line from the tragic play Cato by Joseph Addison. In the play, the title character says: “What a pity it is that we can die but once to serve our country.”

6Washington’s Double Agent

Things went from bad to worse after Washington lost Long Island. The British pushed the colonials out of Manhattan, then New York, and finally New Jersey. By early December 1776, the Americans had crossed the Delaware River into Pennsylvania and were awaiting developments. Washington’s men were hungry and low on supplies, their numbers cut in half by illness, desertions, and expirations of enlistments. Morale plummeted, and with Christmas coming, it was clear more men would either desert or go home after their enlistments lapsed. Washington badly needed a victory.

Enter John Honeyman, a butcher with the reputation as a loyalist to the English crown. Born in Ireland, Honeyman served in the British army in Canada where he fought in the battle of the Plains of Abraham (1759). He was honorably discharged and moved to Philadelphia in 1775 (where some say he first met Washington). According to his grandson, Honeyman met Washington at Fort Lee, New Jersey, in November 1776 and offered his services. (Why Honeyman, who was already hated as a Tory in his hometown of Griggstown, New Jersey, would switch sides is not entirely clear.)

Regardless, Washington accepted Honeyman’s help and told him that he needed to continue to pretend to be a loyalist. Once the colonial army marched south to the Delaware River, Honeyman was to offer his services as a butcher to the pursuing Brits. As a butcher, Honeyman would travel with them and care for their cattle, occasionally cutting them up as needed. As a camp follower, Honeyman could observe the enemy’s dispositions, fortifications, and movements. Honeyman would be on his own: There would be no other agents to support him and no couriers. If Honeyman had valuable information, he was to pretend to be captured by Washington’s sentries and the commander in chief would have Honeyman brought to his tent.

In late December, that’s allegedly what happened. Honeyman was wandering along the Delaware claiming to be hunting for his cattle when he was captured by colonial sentries and taken to Washington’s tent. Once there, Honeyman gave him information about the Hessian soldiers bivouacked across the river at Trenton who he said were lax in their discipline. Washington then staged a distraction while Honeyman escaped. When he returned to Trenton, he told the Hessians that the colonials were too disorganized and dispirited to pose a threat.

On Christmas, Washington’s forces crossed the Delaware River and attacked the Hessians the next morning. The Hessians, either intoxicated or hung-over from the previous night’s celebrations, were quickly overwhelmed by the colonials. Washington captured 900 Hessians and sustained only two casualties. It was the kind of victory the Americans badly needed.

Recently, historians have questioned whether Honeyman actually worked for Washington as a spy. They claim Honeyman was never anything but a loyalist and if he did supply Washington with valuable information about Trenton, it was given reluctantly. Indeed, Honeyman and his family would continue to be harassed as Tories long after the Trenton battle. Honeyman was even twice arrested for treason by the New Jersey authorities and twice threatened with the seizure of his property. Oddly, Honeyman’s indictments were squashed and his property never seized, leading many to speculate that Washington intervened. Evidence either way is scanty.

5 Lydia Darragh Warns Washington

After Nathan Hale’s execution, Washington searched for civilians experienced in spycraft to work for him. Nathaniel Sackett was a New York City merchant who had been on the New York Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies, basically a spy hunting committee. In February 1777, Washington commissioned Sackett to form and run a spy ring in his hometown, offering him $500 initially and $50 a month thereafter. While Sackett would operate the ring for only a few months, his operatives did achieve one important intelligence coup. By spring it was clear that Howe would soon go on the offensive, and Washington was desperate to determine where Howe was headed. In March, one of Sackett’s agents—an unnamed woman married to a Tory—observed that the British were building flat-bottomed boats to be used, she believed, to attack Philadelphia.

Sackett’s agent was correct. The British troops used the boats to travel close to Philly. On September 11, the redcoats beat Washington at Brandywine Creek (the battlefield as it appears today is shown above) and entered Philadelphia two weeks later. Washington immediately set up a spy ring in the heart of the City of Brotherly Love and assigned Major John Clark, a man familiar with the area, to run it.

Clark quickly set up a network of spies, giving them simple aliases like “Old Lady” and “Farmer.” Many of his agents were Quakers living in the area. Quakers were perfect spies because they were pacifists, forced to be neutral in any war. Few would suspect them if they secretly picked a side.

One Quaker, Lydia Darragh, spied on the Brits independently of Clark and his network. Born in Ireland 48 years earlier, Darragh was a midwife, the wife of a teacher, and a mother of five. One of her children, Charles, had broken with the Quakers and joined Washington’s army, camped in nearby Whitemarsh.

When the British took over Philadelphia, General Howe took the house directly across the street from the Darragh residence and used it as his headquarters. Redcoat officers suddenly became commonplace in the street, and Lydia quickly realized that she could gather valuable information through observation and eavesdropping.

Whenever she did have information, her husband, William, would write a coded message on a tiny piece of paper that Lydia would sew under the fabric top of a button. She would then sew the button to her 14-year-old son John’s coat. John would walk to Whitemarsh and deliver the button and message to Charles, who would forward it to Washington.

The Darragh house had a large back room. That fall, General Howe demanded that the Darragh family evacuate the house so it could be used for staff meetings. Lydia convinced Howe that they were harmless Quakers, so the general allowed William and Lydia to stay while the children were sent to a relative outside the city.

On December 2, Howe held an important meeting in the Darraghs’ back room and insisted the couple retire to their rooms and stay there. Lydia, however, snuck into a room adjoining the meeting and hid in a closet. She was shocked to hear them planning a surprise attack on the Continentals at Whitemarsh on December 5.

The next morning, Lydia acquired a pass to cross the British lines so she could visit her children and pick up a bag of flour at the Frankford Mill. During her journey, Lydia ran into an American officer and told him of the impending offensive. The officer forwarded the warning to Washington as Lydia returned home.

Washington was already aware that Howe was up to something. Clark’s agents had already passed along intelligence that the Brits were making preparations for battle, but when and where they were to attack was not known until Washington received Lydia’s message.

When the redcoats appeared at Whitemarsh on December 5, Washington was waiting for them. Surprised, Howe turned around and headed back to Philadelphia. Lydia and William were immediately suspected of tipping Washington off, but when Howe’s officer appeared at the door, Lydia convinced him of their innocence.

Clark’s spy ring continued to supply Washington with valuable intelligence throughout the winter of 1777-1778. When Clark’s agent reported that Howe was going to hunker down for the winter in Philly, Washington decided to camp at nearby Valley Forge.

4 The Culper Ring Saves The French

In February 1778, while Washington’s men suffered from hunger and hardship at Valley Forge, France signed a treaty to fight with America against England. That same month, Howe, stung by his failure to end the war, was replaced by General Henry Clinton as commander in chief of the British forces. Concerned that the French might attack New York City, London ordered Clinton to evacuate Philadelphia and reinforce the NYC garrison.

The French fleet was indeed on its way, bound for British-occupied Newport, Rhode Island, and they asked Washington if he could ascertain what the British navy in New York harbor was up to. A bit of serendipity intervened that August when an artillery lieutenant named Caleb Brewster offered his services to Washington. Brewster was an ex-seaman who grew up near the Long Island Sound. Washington readily accepted his offer, and Brewster used a whale boat to reconnoiter the New York waters. On August 27, Brewster reported that the British were aware of the French fleet’s destination and were sending their own fleet to Newport. That fleet, together with a terrible storm, forced the French to abandon their plans to take Newport.

Washington decided to keep Brewster in place and build a spy ring around him. To do that, Washington turned to Major Benjamin Tallmadge (pictured above), who was a childhood acquaintance of Brewster. Not only was Tallmadge familiar with Brewster and the Long Island Sound, he had learned spycraft under Nathaniel Sackett and was highly motivated, since he and Nathan Hale had been friends at Yale.

Washington sent Tallmadge’s dragoon troop to operate in the lower Hudson Valley and Connecticut coastal area, hunting Tories and parrying British raids and incursions. Brewster would act as courier, carrying messages from Long Island to the Colonial-controlled Connecticut shore in his whale boat. He would then meet Tallmadge with the fruits of their spy ring.

Tallmadge also recruited another Setauket acquaintance, Abraham Woodhull, and a distant relative, Anna Strong. Neither Woodhull nor Brewster had much access to the British military in New York. For that they recruited Robert Townsend, a merchant who lived in Woodhull’s sister’s boardinghouse in Manhattan. Townsend and other Setauket residents collected snippets of information to send down the line directly to Washington.

For the purposes of correspondence, Woodhull was dubbed Samuel Culper, a subtle nod to Culpeper County in Washington’s home state of Virginia. When Townsend was named Samuel Culper Jr., the entire spy ring was called the Culper Ring.

Two years later, in July 1780, the French once again tried to land at Newport. As the British had abandoned the port in 1779, the French landed unopposed. Once again, Washington asked his spies to find out how the redcoats would react to France’s arrival. Townsend was part owner of a coffeehouse where Clinton’s officers came to talk, often of future operations. Townsend soon learned that Clinton was massing his army on the northern tip of Long Island for an offensive against Newport.

Townsend smuggled his intelligence to Washington using invisible ink between the lines of a letter addressed to a Tory. Just 10 days after he requested information, Washington had a report from the Culper Ring that not only was Clinton marching 8,000 redcoats straight at Newport, nine British warships were also en route. Clearly, Clinton wanted to strike the French forces before they had time to build their defensive works.

While the French hurried their preparations for defending Newport, Washington created a fictitious diversionary offensive against Manhattan. He had a local farmer “find” the plans for the offensive and deliver them to a British outpost. Washington then began marching his army toward New York City. Clinton recalled his troops to protect the city from what he thought was an imminent attack. The French were thus saved from a British offensive.

3 The Culper Ring Uncovers Benedict Arnold’s Betrayal

Tallmadge’s Culper Ring used sophisticated espionage techniques such as codes, aliases, and invisible ink, making it Washington’s most successful spy ring. The group used invisible ink—called “stain” or “white ink”—and a codebook based on John Entick’s 1771 New Latin and English Dictionary. The spy could write out words using a transposed alphabet that could be decoded easily with the key.

Meanwhile, Washington was unaware that he had a problem within his ranks. One of his most famous generals, Benedict Arnold, had evolved from ardent patriot to traitor in just four short years. At the beginning of the war, Arnold passionately supported the revolution, so much so that he used his own money to train his men. Unfortunately, the new colonial government was incapable of repaying him.

Hero of Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga, Arnold could justly claim to have rescued the revolutionary effort not once but twice. Both times he’d paid for his brilliance with battle wounds, but he was consistently passed over for promotion. Worse, his stubborn thigh wound made it impossible for him to retake the field and pursue the glories of battle his ego required. He was given an administrative command over Philadelphia which gave him time to nurse his grudges and get in trouble.

Trouble came in form of a beautiful, charismatic Philadelphian named Margaret “Peggy” Shippen. Arnold met Shippen in the summer of 1778, around the time she turned 18. A romance blossomed, despite the fact that Shippen was a known loyalist and was still in contact with Major John Andre, an officer in His Majesty’s service she met during the British occupation. Shippen came from wealth, and Arnold’s romance of her soon overwhelmed his meager salary. By the time the pair married in April 1779, Arnold was deeply in debt, a trap Shippen may have set on the advice of Andre.

A month later, probably with his wife’s help, Arnold first contacted Andre with an offer to betray his country. Arnold wanted money and the same rank in the British army. For a year, Arnold and Andre dickered over the terms, but by the summer of 1780, the issue was settled enough for Arnold to start supplying top-rate intelligence, including the news that the French were about to land at Newport, Rhode Island. And when Arnold was offered command of West Point, he offered to allow the British to capture it.

Just when the members of the Culper Ring started intercepting Arnold’s correspondence to the British is unknown, but it appears to have happened sometime in July or August 1780. On July 30, Arnold was officially named to head West Point and on August 15, the British agreed to pay him 20,000 pounds sterling (about £3.2 million today or nearly $5 million).

On September 3, Arnold sent a letter to the British to finalize his meeting with Andre, but someone—possibly someone in the Culper Ring—turned the letter into gibberish. When Arnold attempted to cross the British lines on September 11, they fired upon his boat and forced him to cancel the meeting. When they tried again to meet on September 23, Andre was captured, but Arnold and Peggy slipped through the net to join the British.

When Tallmadge met Andre, the latter asked what was going to happen to him. Tallmadge responded with a story about his good friend Nathan Hale, executed by Andre’s friend General Howe. He finished the story with: “Similar will be your fate.” Andre was hung on October 2. Arnold was given a commission as a general in the British army, but he was paid only £5,000 because his plot failed.

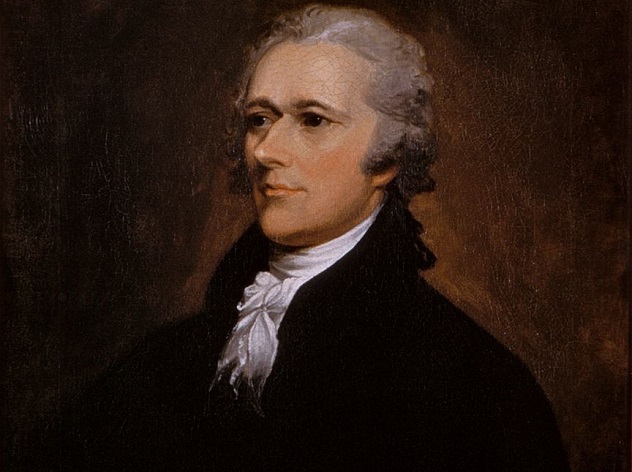

2 Hercules Mulligan And Cato Save Washington’s Life Twice

Perhaps the least known and most important of America’s first spies, Hercules Mulligan was a New York City tailor who had immigrated from Ireland when he was six. He was a member of the New York chapter of the Sons of Liberty, one of the more aggressive anti-British agitation groups. In July 1776, Mulligan personally led a mob to New York’s Bowling Green and pulled down the equestrian statue of King George III. Mulligan and his compatriots melted down the lead statue to be used as bullets against the king’s redcoats.

Three years earlier, Mulligan opened his home to a teenager from St. Croix Island in the West Indies named Alexander Hamilton (pictured above). The young man had come to New York to study at King’s College (now Columbia University) but received his most important education at Mulligan’s dinner table, discussing America’s grievances against the British Empire. Hamilton was a loyalist, but joined the patriot cause after hearing Mulligan’s arguments.

When General Howe captured NYC in September 1776, it’s not surprising that Mulligan was arrested and jailed at the Provost Prison, but he managed to convince the Brits to release him, saying he was no longer a patriot. The following March, Hamilton became Washington’s aide and suggested Mulligan as yet another NYC spy.

As one of the city’s premiere tailors and clothiers, Brits regularly frequented Mulligan’s Queen Street shop to have their uniforms mended or altered. It was during the fittings that the Irishman would pump the officers for information. Once he had enough intelligence, his slave Cato would take the Hudson River ferry to New Jersey where he would drop off a parcel with the information at a safe house. An express rider would then rewrap the parcel and deliver it directly to Washington.

While Mulligan occasionally cooperated with the Culper Ring, he usually operated only with Cato and a translator named Hyam Salomon. Late one night in the winter of 1779, a British officer entered Mulligan’s shop demanding a watch coat immediately. When Mulligan asked why he was in a hurry, the officer explained he had a mission that very night to capture Washington and boasted “before another day, we’ll have the rebel general in our hands.” Washington that night was meeting some of his subordinates, and the Brits had discovered the location of the meeting and planned to set a trap. Cato, however, was quickly sent to New Jersey to warn Washington. On Mulligan’s word, Washington avoided capture.

It happened again in February 1781, when Washington was en route to Newport, Rhode Island, to meet with the French general, Rochambeau. Mulligan’s brother Hugh owned an import-export firm the British ordered supplies from. When a rush order came in, an officer told Hugh that 300 cavalrymen were headed to New London, Connecticut, to intercept Washington. After he received Mulligan’s warning, Washington had his men ambush the horsemen when they arrived at New London.

1 Armistead’s Intelligence Coup

With the entrance of the French into the war in 1778, the British attempted to turn the southern colonies against the northern ones. But while troops under General Charles Cornwallis could take coastal cities like Savannah and Charleston, they could not hold interior sections of the Carolinas for long.

In the fall of 1780, Cornwallis had marched into North Carolina, bent on attacking Washington from the south while Clinton attacked from the north. But a series of colonial victories forced Cornwallis to retreat to South Carolina. To relieve the pressure on Cornwallis, Clinton sent Benedict Arnold to Virginia to capture Richmond just before New Year’s Day. Arnold’s men plundered and burned the state capitol.

Just east of Richmond was the plantation of William Armistead. In March 1781, General Marquis de Lafayette and 1,200 colonials arrived in nearby Yorktown, Virginia, to harass Arnold’s army. One of Armistead’s slaves, James, asked his master if he could join Lafayette’s army to drive the British invaders from the Old Dominion. James surely knew that the British had offered to emancipate any American slave that helped them. And yet he wanted to fight for the patriot cause. William consented.

When James Armistead appeared in Lafayette’s camp, the French general saw the value of a man who knew the area. Lafayette asked him to make his way to Arnold’s camp, pretend he was a runaway slave, and offer his services as a scout. Arnold accepted Armistead’s story and offer and gave him freedom to wander the British camp, listening to conversations around the campfires.

Armistead became so trusted that when Arnold’s army merged with the Cornwallis forces in May, Armistead was allowed to remain as a scout for Cornwallis. In July, Armistead sent word to Lafayette that Cornwallis was planning to move down the Virginia Peninsula to Yorktown to await supplies.

At the time, Washington was planning an offensive with the help of the French against Clinton in New York. But when Lafayette forwarded Armistead’s message, Washington realized that Cornwallis could easily be cornered at Yorktown. He then rushed his army south to surround Cornwallis while the French fleet blockaded the coast. In October, Cornwallis was forced to surrender his army, essentially ending the war.

Despite his invaluable service to the Revolution, James was forced to return to William Armistead’s plantation as a slave. While the new republic freed slaves who fought for the cause, James had never donned a uniform. It was only with the help of Lafayette that James Armistead was finally emancipated in 1787.

Steve is the author of 366 Days in Abraham Lincoln’s Presidency: The Private, Political, and Military Decisions of America’s Greatest President and has written for KnowledgeNuts.