History

History  History

History  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

10 Dragons From British Folklore

Although Beowulf and Saint George are the most famous dragon slayers in British mythology, even they cannot defeat all the dragons that appear in the larger folklore of England, Wales, and Scotland. Many of these dragons, or “worms” as they are frequently called, have stories which link them with fixed locations throughout the UK. As such, a large portion of Britain’s dragons are part of local folktales that have been handed down over centuries.

10The Red And White Dragons

The image of the dragon is an integral part of Welsh identity. As evidence of this, a red dragon is emblazoned on the country’s flag as a symbol of Welsh pride and nationalism. This dragon, along with a white dragon, appear in The Mabinogion—one of the earliest examples of British prose literature and an important collection of Welsh mythology.

Compiled sometime between the 12th and 13th centuries, the Mabinogion contains numerous tales that have become famous across the world, such as some of the earliest accounts of the Celtic leader King Arthur. “Lludd and Llefelys,” another famous tale, details the important war between the red dragon and the invading white dragon.

In the story, the foreign white dragon is so fearsome that its cries cause women to miscarry and its mere presence is enough to kill livestock and ruin crops. Determined to rid his kingdom of this menace, King Lludd of Britain visits his brother Llefelys in France.

Llefelys tells his brother to prepare a pit filled with mead and cover it with cloth. After Lludd completes this task, the white dragon begins to drink from the pit and falls into a drunken stupor. With the monster asleep, Lludd captures the dragon and imprisons it in Dinas Emrys, a wooden hillock in Wales.

One of the more common interpretations of this story is that the red dragon represents the native Celtic inhabitants of Britain while the white dragon is a symbol of the Germanic Anglo-Saxons who began invading England in the fifth century.

A related idea is that the white dragon is the symbol of the Saxon warlord Vortigern while the red dragon is the flag of King Arthur’s forces. Either way, “Lludd and Llefelys” does show a close relationship between Celtic Britain and Gaul (today’s France), which may make this story’s origins even older than the fifth century.

9Dragon Of Loschy Hill

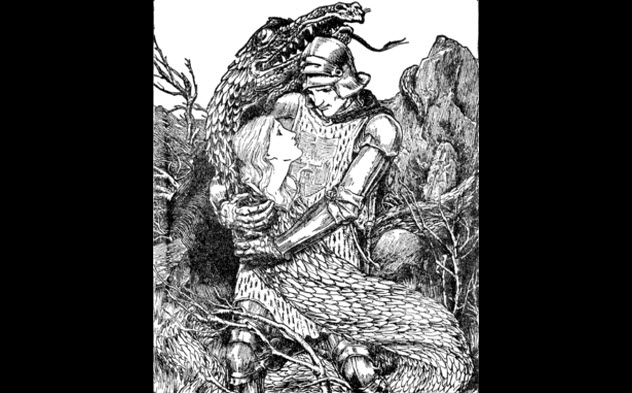

“The Dragon of Loschy Hill” is a tragic Yorkshire tale that is recounted by Reverend Thomas Parkinson in his 1888 book Yorkshire Legends and Traditions. According to Parkinson’s account, a large dragon once haunted a wooded area later known as Loschy’s Hill in the parish of Stonegrave. As the dragon terrified local villagers, a brave knight named Peter Loschy decided to kill the beast once and for all. While wearing a special suit of armor that featured several razor blades, Loschy and a trusted dog set out to find the dragon.

Feeling confident that the knight would be just another meal, the dragon wrapped itself around Loschy’s armor and tried to squeeze the human into eternal submission. Loschy’s armor gave the dragon numerous cuts, but all of them healed quickly. Although stunned by the dragon’s supernatural powers, Loschy managed to cut off pieces of the dragon’s skin with his sword. His dog then carried the pieces to Nunnington Church.

Loschy and his dog managed to dismember the dragon so thoroughly that it could not regenerate. Loschy was so overjoyed that he didn’t realize that his face was coated in the dragon’s poison. Upon licking his master’s face, the faithful dog ingested the poison and died. In turn, the poison fumes became too much for Loschy, and he died by his dog’s side.

As a show of gratitude, the villagers of Stonegrave buried Loschy next his dog in Nunnington Church, where stone engravings retell the story for all to see.

8Sockburn Worm

The Sockburn worm is a wyvern, not a dragon. Although a relative of the dragon, northern European folklore depicts wyverns as smaller creatures with the head of a dragon, the body of a snake, the wings of a bat, and two legs that protrude above a long, serpentlike tail. Despite being smaller than dragons, wyverns were known for being exceptionally vicious. The Sockburn worm was no different.

Not long after the Norman Conquest, the Sockburn worm began terrorizing the country surrounding the River Tees in County Durham. The Sockburn worm used its ability to fly and its poisonous breath to wreak havoc all across the Sockburn Peninsula.

Realizing that the wyvern must be killed to save the realm, a knight named Sir John Conyers visited a church and offered up the life of his only son to God in preparation for the battle. A document known as the Bowes Manuscript asserts that Conyers not only killed the wyvern but earned land and a title because of his heroism.

Some historians have suggested that the Sockburn worm represents a marauding Danish warrior while others see Conyers as a Norman knight who helped to legitimize Anglo-French rule in the northeast. Whatever the truth, the weapon that Conyers supposedly used to kill the Sockburn worm is still on display in the Durham Cathedral and is called the Conyers falchion.

7Mester Stoor Worm

Located in the far north of Scotland, the Orkney Islands have an ancient history that stretches all the way back to the Stone Age. During the ninth century, Orkney fell prey to numerous Viking raids from Norway. Ultimately, the islands were settled by Scandinavians who helped to annex the islands for Norwegian and later Dano-Norwegian kings.

As the Orkneys offered a way for Germanic and Celtic cultures to interact, the islands became home to unique folklore. As part of that folklore, the Mester stoor worm remains a thoroughly Orcadian tale.

As the legend goes, the Mester stoor worm was a gigantic sea serpent that could wrap itself around the entire world. When it moved, the Mester stoor worm caused earthquakes and other natural disasters. Owing to the monster’s poisonous breath and its habit of smashing ships to pieces, most knights steered clear of the creature.

One day, a powerful wizard promised the king that the sea beast could be killed if the king gave up his daughter to the wizard. Not wanting to lose his daughter, the king offered the entire kingdom to any brave warrior who killed the Mester stoor worm.

An unlikely hero emerged by the name of Assipattle, a slow-witted farm boy who killed the dragon by guiding a ship into the dragon’s stomach. There, Assipattle applied burning peat to the dragon’s liver, which eventually caused an explosion that forever rid the world of the Mester stoor worm.

According to the legend, the dead beast did bring about a positive change, for the dragon’s scattered teeth created the Orkney Islands.

6Bignor Hill Dragon

Not much is known about the Bignor Hill dragon. Its name appears only sporadically in the historical record, yet the few clues about the beast are quite tantalizing. In the 19th century, The Gentleman’s Magazine recorded that the local inhabitants of Bignor Hill, an area in Sussex dotted with Roman roads, believed that an ancient Celtic dragon lived on top of a nearby hill.

Some folktales spoke of the surrounding hills as being part of the dragon’s skinfolds while others pointed out that the dragon’s den was close to a ruined Roman villa. This later tale is interesting because it may highlight an interpretation of the Bignor Hill dragon as some sort of holdout from the Roman occupation of Britain, which introduced the Roman religion on the island. The notion that the dragon is of Celtic origin likewise points to a Christian demonization of pagan practices.

Although the origins of the Bignor Hill dragon are unknown, Sussex is awash in dragon tales, making it a treasure trove of dragon folklore.

5Lyminster Knucker

Lyminster, Sussex, was once home to a knucker. Based on the Old English word nicor, which means “water dragon,” knuckers are predominately found in knuckerholes, ponds that are present throughout Sussex. The Lyminster knucker lived in one such knuckerhole near the major church of Lyminster.

The knucker began its reign of terror by snatching away livestock. Then the water dragon began dragging away all the young girls from the village until the only maiden left was the king’s daughter. With few options left, the king of Sussex offered his daughter as the prize for anyone who could slay the dragon.

Three different versions of the legend record three different heroes. One legend has it that a wandering knight killed the dragon before taking the princess as his wife. In another version, a local man named Jim Puttock kills the dragon by feeding it poisoned pudding. A third version says that a man named Jim Pulk slays the dragon with poisoned pudding but forgets to wash the dragon’s poison off his skin and dies as a result.

These competing versions merely highlight the importance of the Lyminster knucker story to Sussex folklore. St. Mary Magdalene’s Church in Lyminster is still known as the home of the “Slayer’s Slab“—a tomb that supposedly houses the bones of the man who killed the Lyminster knucker.

4Laidly Worm Of Spindleston Heugh

“The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh” began as a Northumbrian ballad that was passed down through song in northern England. The story begins with the king of Northumbria, who lived inside Bamburgh Castle with his wife and children. When the first queen died, the king took a malicious witch as his bride. The king’s strong son, Childe Wynd, is out to sea, so there is no one in the castle who can stop the witch’s evil plans.

Jealous of the beautiful Princess Margaret, the witch turns the young girl into a dragon. The princess remains that way until Childe Wynd returns and kisses the dragon. The prince’s kiss breaks the spell, which allows the prince to claim the throne. As revenge, Childe Wynde curses the witch and turns her into a toad.

This is just one version of this classic tale. In another version, the castle is called Bamborough and the witch’s curse is far worse. Princess Margaret becomes an uncontrollably hungry dragon that must feast upon the area livestock. However, both versions draw inspiration from the Icelandic saga of the shape-shifter Alsol and her lover Hjalmter.

3The Mordiford Wyvern

The story of Maud and the Mordiford wyvern is a rather unusual legend. Set in the Herefordshire village of Mordiford, the story concerns a young girl named Maud who finds a baby wyvern while out walking one morning. Maud takes the small creature back to her home as a pet and feeds it milk regularly.

As the creature grows older, it develops a taste for human flesh and begins dining on the Mordiford villagers. Despite its cruelty, the wyvern remains loyal to Maud and refuses to eat her. However, even Maud cannot get the wyvern to stop its killing spree. It makes its home on a nearby ridge and its constant movements back and forth create the Serpent Path, a twisting road that ends at a local river.

Several versions of the creature’s demise exist. In one, the scion of the Garston family manages to kill the beast after a fierce ambush. Another version says that a condemned criminal killed the wyvern to escape capital punishment.

2The Dragon Of Longwitton

For a time, the inhabitants of Longwitton, Northumberland, were barred from three holy wells. This was not because the water was poisoned but rather because a fearsome dragon kept them away. A hero did not appear until a knight named Sir Guy, Earl of Warwick accepted the task of killing the dragon.

For three days, Sir Guy and the dragon fought each other. During that time, Sir Guy grew disenchanted because each cut and stab did nothing to the dragon. Once struck, the dragon simply used magic to heal its own wounds.

On the third day, Sir Guy noticed that the dragon kept its tail inside one of the wells throughout the battle. Realizing that the sacred waters allowed the dragon to constantly heal itself, Sir Guy persuaded the dragon to move away from the wells entirely, thereby leaving it vulnerable. Once away from the holy waters, Sir Guy easily managed to kill the creature.

More detailed versions of the story proclaim that the waters were known for their healing properties throughout Northumbria, and as such, the dragon coveted the wells for its own purposes. In some tales, the brave knight also uses a magic ointment to protect himself from the dragon’s breath.

1Worm Of Linton

According to 12th-century stories from the Scottish Borders, the Linton worm lived in the “Worm’s Den”—a hill near the village of Linton in Roxburghshire. At dusk and dawn, the dragon left its den to prey upon sheep, cows, and people. All the weapons used against the creature proved useless, and before long, Linton had been reduced to a wasteland.

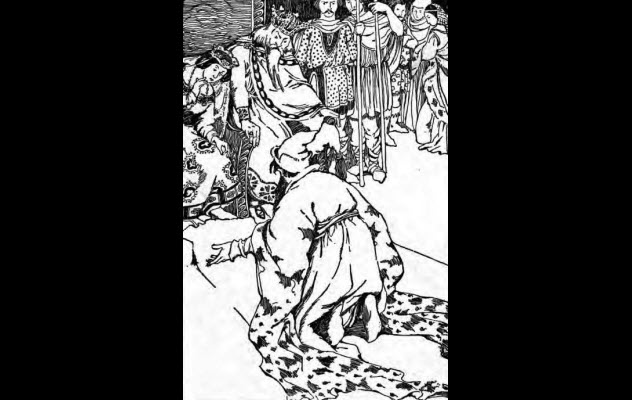

When word of the dragon reached the ears of William (or John) de Somerville, the Laird of Lariston, the courageous knight decided to act. Riding north, de Somerville noticed that the dragon frequently consumed everything that stood in its way. However, when faced with something too large to swallow, the dragon would lie still with its mouth open.

Realizing that this made the dragon vulnerable, de Somerville had a blacksmith create an iron spear with a wheel on its tip. De Somerville placed burning peat on top of the wheel. When he journeyed inside the worm’s mouth on horseback, he placed the fire inside of the dragon, creating a fatal wound.

In its death throes, the Linton worm’s thrashing body created the many hills that today populate the region. For his actions, Linton Church (or Kirk) created a carved stone to record the story for posterity.

In some versions, the death of the Linton worm occurred during the reign of King William the Lion, who ruled Scotland from 1143 until 1214. Supposedly, King William greeted de Somerville as “my gallant Saint George” to enhance the nobleman’s confidence. Also, besides the carved stone in Linton Church, de Somerville’s victory is supposedly commemorated by the de Somerville coat of arms, which features a green, fire-breathing dragon on top of the tympanum.

Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. His work has appeared in The Atlantic, The Weekly Standard, Listverse, Metal Injection, and others. He currently blogs at literarytrebuchet.blogspot.com.