Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

10 Important Prehistoric Individuals Worth Knowing

Michael Crichton, author of Jurassic Park, once said, “If you don’t know history, then you don’t know anything. You are a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.” Indeed, history is important. It helps us understand who we are, where we came from, and most importantly, where we’re going. Like Robert Pen Warren once wrote, “History . . . can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and our common humanity, so that we can better face the future.”

But how about prehistory? Some people might say it’s irrelevant, but experts will tell you that examining prehistory is just as important as studying history. Thanks to advances in technology, especially in genetic analysis, we are starting to gain a deeper understanding how prehumans and humans evolved and lived. By studying the lives of prehistoric individuals, we can gain an in-depth knowledge of our humanity and a tiny glimpse of our future.

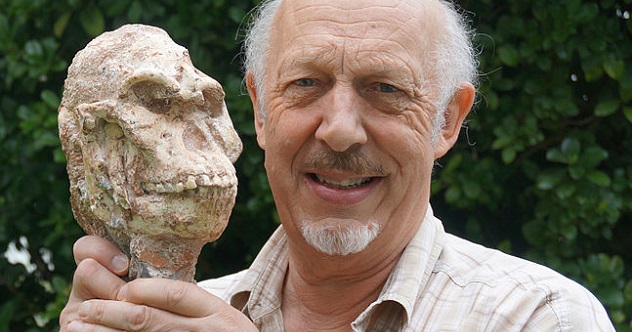

10 Little Foot

You’ve probably heard of Lucy, the famed human ancestor who lived about 3.2 million years ago, but how about Little Foot? Just like Lucy, Little Foot is an australopithecine, or prehuman, that lived in Africa about 3.7 million years ago. Sadly, Little Foot died from falling into a narrow shaft in the Sterkfontein Caves. His skeletal remains were discovered about 20 years ago by Ronald Clarke (pictured above with Little Foot’s skull), a paleoanthropologist from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa.

Little Foot and Lucy roamed the Earth at approximately the same time. However, they weren’t the same species. Lucy belonged to the species Australopithecus afarensis, while Little Foot’s species remains unknown. Some experts say that he’s a member of A. africanus, a species characterized by round skulls, large brains, and small teeth. Others say he’s an example of A. prometheus, a species known for large cheeks and long, flat faces.

Little Foot’s existence suggests that several prehuman species roamed Africa at approximately the same time. Furthermore, Lucy’s lesser-known friend may eventually help scientists determine which region and which species “gave rise to humanity.”

9 The Neolithic Woman And Her Baby

In 2008, scientists discovered traces of human tuberculosis in the remains of a Neolithic woman and her baby. The skeletal remains were estimated to be around 9,000 years old and were found in Atlit-Yam, a submerged prehistoric village located off the coast of Israel (pictured above). As for the disease itself, tuberculosis—commonly known as TB—kills an estimated two million people each year.

Before the discovery of the Neolithic woman and her baby, the oldest archaeological evidence of TB was a 6,000-year-old skeleton unearthed in Italy. It’s interesting to note that the skeletal remains of the Neolithic woman and her baby challenged the theory that TB originally spread from cattle to humans.

Bovine TB affects cattle, while human TB affects people. Though the Neolithic woman lived around the period when mankind started transitioning from hunter-gatherers to farmers, no trace of bovine TB was found at the Atlit-Yam site. This simply means that human TB might be older than bovine TB. It also indicates that perhaps the theory that TB originated from cattle might not be entirely accurate.

8 The Late Stone Age Family

In 2005, researchers discovered a grave near Eulau, Germany, that contained the remains of four prehistoric people: a male adult, a female adult, and two male children. The skeletons are estimated to be around 4,600 years old. At first glance, you probably wouldn’t notice anything interesting about this archaeological finding, but a more in-depth look would prove otherwise.

The way the skeletons were buried suggested that they were a family. The male adult was curled up on his side, facing one of the children. The female was also on her side, hugging the other child. DNA testing confirmed that the remains were indeed a family.

These people are important since they provide the oldest genetic evidence for a nuclear family. Furthermore, their remains suggest that during the Late Stone Age, biological relationships were the focus of society. Wounds on the skeletons suggest the family died a violent death. Most likely, they died defending themselves during a raid where arrows and stone axes were used.

7 The Hindu Leper

The Hindu Leper is an unnamed man estimated to have lived 4,000 years ago in prehistoric India. He is also considered to have the earliest known case of leprosy.

Also called Hansen’s disease, leprosy has long plagued the human race. Thankfully, this dreadful disease is now curable. Despite this, leprosy remains one of science’s greatest riddles, mainly because the bacteria responsible is difficult to culture for research. (Also, aside from humans, the only other host animal is the armadillo.) Scientists are not certain as to when and where leprosy originated, but they suggest this disease might have started either in Asia or Africa.

Before the discovery of the Hindu Leper’s remains, skeletal evidence related to leprosy was limited to 300–400 BC in Egypt and Thailand. Thanks to the Hindu Leper, scientists now have even older evidence of the disease. More importantly, the Hindu Leper’s DNA might help experts understand how leprosy “spread in early human history.”

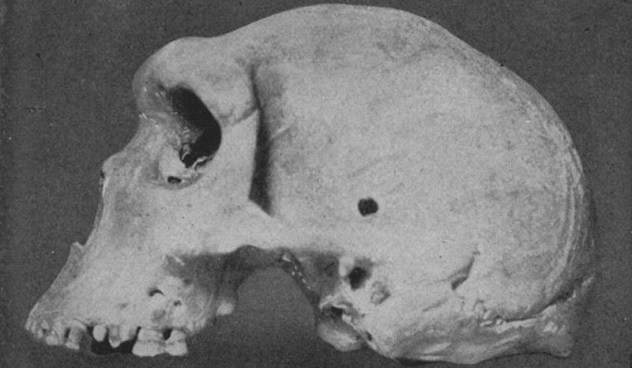

6 The Rhodesian Man

In 1921, a Swiss miner named Zwigelaar was working in a lead and zinc mine in Kabwe, Zambia, when he discovered a skull. However, this was no ordinary skull. It was a fossilized cranium that belonged to an extinct human species. While it was initially dubbed Homo rhodesiensis, it has more recently been classified as an example of H. heidelbergensis.

Nicknamed the Rhodesian Man, the skull was found along with a limb, a sacrum, and a pelvis. Aside from Rhodesian Man, the fossilized remains also go by names such as the Kabwe Cranium and the Broken Hill Cranium.

From the time of its discovery until the 1970s, the Rhodesian Man was estimated to be around 30,000–40,000 years old. This caused scientists to theorize that Eurasian prehumans might have been more advanced in developing modern anatomy than the African prehuman.

However, this theory was proven incorrect when scientists realized Rhodesian Man was much older than initially suspected. Today, researchers now estimate the remains are between 300,000–500,000 years old, which explains why Rhodesian Man was less evolved than its more recent Eurasian counterparts. Nevertheless, the discovery of Rhodesian Man was incredibly important as this was the first time scientists had uncovered the remains of pre-modern man in Africa.

5 Java Man

During the 19th century, evolutionists were obsessed with the idea of discovering the ancestral “missing link” between apes and humans. One of these scientists was Eugene Dubois, a Dutch geologist and anatomist. Influenced by the theories of Ernst Haeckel and Alfred Wallace, Dubois went to Indonesia in search of the highly prized missing link.

Instead, he discovered the Java Man.

The Java Man is an extinct early human whose fossilized remains were found in Java, Indonesia. It was discovered by Dubois in 1891 at Trinil, an important paleoanthropological site on the banks of the Solo River. Scientists suggested the Java Man stood 170 cm (5’8”) and was between 500,000 and 1.5 million years old. In 1894, Dubois published his findings, but much to his dismay, the public and his fellow evolutionists rejected his claims.

The Java Man might not be the missing link, but it is acknowledged by scientists as the first discovered remains of the Homo erectus species, possibly our evolutionary ancestor.

4 The Tooth

The individuals discussed in this list had most of their skeletons intact when they were discovered. However, the Tooth is an exception. The Tooth has no head, body, legs, or anything else for that matter. It’s simply a tooth that once belonged to a prehistoric human . . . and it might hold the key to the evolution of our humanity.

The Tooth was discovered in southwestern France on July 2015 by two French teenagers serving as volunteer archaeologists. The teens were part of a group excavating one of the world’s most important prehistoric sites: Tautavel. Though its skeleton isn’t complete, the Tooth may be very important to scientific study. Some scientists are even calling it a major discovery.

Experts do not know if the tooth belonged to a male or female, but they are certain that it is adult, and that it is at least 560,000 years old. The discovery of the Tooth is significant since it is the oldest human body part ever discovered in France. More importantly, it fills “a gap between the very few oldest human fossils, notably found in Spain and Germany, and more recent ones.”

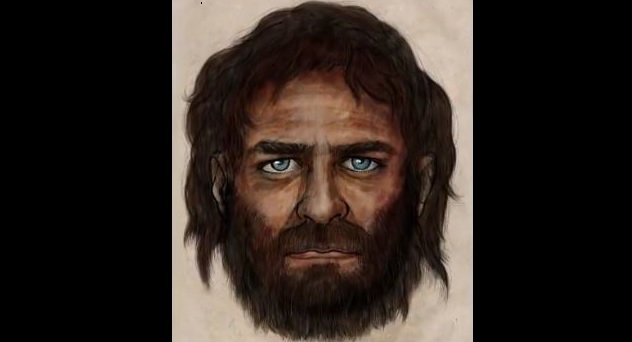

3 La Brana I

There is a theory that says Europeans started to develop a lighter skin tone about 40,000 years ago, after they moved from tropical Africa into continental Europe. For many years, scientists held this theory to be true, but in 2014, a discovery was made that disproved this long-held assumption.

In 2006, the remains of two Mesolithic men were discovered by a group of cavers at the La Brana-Arintero archaeological site in Valdelugueros, Spain. One of the prehistoric men was dubbed La Brana I. He was a hunter-gatherer. The DNA from La Brana I’s wisdom tooth was examined, and the genetic analysis showed he had dark hair, dark skin, and blue eyes.

This finding was published in 2014 in the scientific journal Nature, disproving the previously held theory. La Brana I is approximately 7,000 years old, so the transition of early Europeans from dark skin to light skin “took longer than previously thought.”

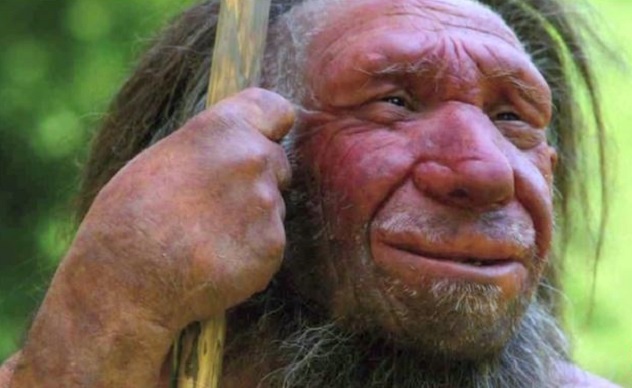

2 The Neanderthal Family

In 2010, archaeologists in Spain discovered the skeletal remains of 12 Neanderthals. The bones were unearthed in a cave in the Asturias region of northern Spain. They were estimated to be 49,000 years old and believed to be one big family. Genetic analysis showed that the family was composed of six adults (three men and three women) and six children, with one of them being an infant.

Tragically, it seems this family met a violent end. They were eaten by their fellow Neanderthals. Cannibalism was common among Neanderthals, but the discovery in northern Spain is remarkable because of how many Neanderthals were killed and devoured.

Experts have ruled out modern humans as the perpetrators of the attack since they had not yet migrated to Europe. As such, the only possible suspects were Neanderthals. Despite the horrifying backstory, scientists are thrilled about this discovery since it’s “the first . . . genetic evidence of a social kin Neanderthal group.”

1 The Mezzena Hybrid

This might come as a surprise, but if you’re Asian or European, then 1–4 percent of your DNA came from Neanderthals. How can this be? New evidence suggests that Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted and interbred for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

One particular piece of evidence that supports this theory is the skeletal remains of a Neanderthal-human hybrid who lived in northern Italy approximately 30,000–40,000 years ago. His remains were found in Riparo di Mezzena, a rock shelter in the Italian region of Monti Lessini.

After conducting genetic analysis, scientists found that the Mezzena hybrid’s mother was a Neanderthal, but his father was a modern human. Experts theorize that modern male humans might have raped female Neanderthals, leading the latter to dislike the former. Even though interbreeding was common among the two species, they did not merge into one single group. The Neanderthals upheld their own cultural identity. Purebred Neanderthals and their culture eventually went extinct, but their DNA continues to exist in some of us today.

When not busy working with MeBook (an app that helps you transform your Facebook into an actual printed book), Paul spends his time writing interesting stuff and creating piano covers. Connect with him on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter.

![Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos] Top 10 Most Important Nude Scenes In Movie History [Videos]](https://listverse.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/sharonstone-150x150.jpg)