Our World

Our World  Our World

Our World  Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

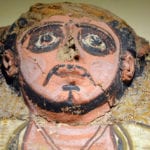

10 Amazing Ancient Funerary Relics

The intricate funerary relics and rituals of the past show just how unimaginative we’ve become in our dealings with the dead. The modern potluck remembrances of the 21st century seem almost without ceremony when stacked against the ceremonial rites of the past, when we struggled to appease the finicky supernatural forces that assured one’s post-mortal domain.

10 Ancient Egyptian Toe Rings

The Ancient Egyptians were accomplished astronomers, naturalists, and early adopters of the toe ring as well. Over the past few years, archaeologists have recovered several corpses fitted with metal toe rings. One perfectly prepared 2,200-year-old mummy from Karnak, a priest named Hornedjitef, sported a golden ring around his left big toe, according to CAT scans. But why?

Elsewhere in Egypt, in a cemetery south of ancient Akhetaten (now called Amarna), two 3,300-year-old non-mummified bodies were also found with rings on their toes, though these relative commoners could apparently only afford a copper alloy. Telltale markings around the men’s digits suggest that they wore their rings while still alive, and further scanning may have revealed why—mystic physical therapy.

Just like the pseudoscientific copper bracelets hawked by modern infomercials, the men likely rocked the rings out of necessity, rather than for fashion. One of the men was a walking injury, displaying several previously fractured ribs, breaks in both forearms and his right foot, and an improperly healed right femur—on the same side that the ring was applied. It’s not certain that this was the reason for the toe bling, and we may never truly know, but it offers a tantalizing hint.

9 The Tomb Of Columbus

Seville’s Catedral de Santa Maria de la Sede houses the intricate tomb of Christopher Columbus. The navigator’s remains are held aloft by four liveried figures, representing each of Spain’s four former kingdoms—Castille, Aragon, Navara, and Leon.

That’s not the whole story. The mammoth cruciform “Columbus Lighthouse” of the Dominican Republic also claims host to the eminent carcass. Constructed in 1992 in Santo Domingo Este, it commemorates the 500-year anniversary of that fateful August in 1492, “when Columbus sailed the ocean blue.”

Why Santo Domingo? Partially due to mishap. After a lifetime of pillage and indigenous rape that would give Vikings pause, Columbus croaked in 1506 and was buried in Valladolid. Deciding that the city was too “working class,” Columbus’s son Diego had papa’s corpse disinterred and sent to sunny Seville. Almost 40 years later, the bones were shipped to Santo Domingo to be immortalized in the stately and newly established Catedral de Santa Maria la Menor.

Columbus rested here for several hundred years until the French kicked the Spanish out, and the bones found their way to Cuba. The Cubans gave the Spanish the boot in 1898, and the bones once again crossed the sea back to Andalusia. Surprisingly, a worker at the Cathedral de Santa Maria la Menor previously stumbled upon a box said to contain the bones of “Don Colon,” a term applied both to Columbus and his son, Diego.

So who’s actually buried at Seville? It appears that at least part of Columbus is, according to genetic analysis. However, parts of his corpse may also reside at Santo Domingo, though the Dominicans are less than willing to pry open the coffin for science.

8 Teotihuacan’s River Of Mercury

In Greek mythology, the river Styx bounds the earthly domain and the hellish underworld Hades, and recently, archaeologists have found the Mesoamerican version—a river of mercury beneath the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent at Teotihuacan, the famed Aztec-named site built thousands of years earlier by unknown peoples.

In the Aztec Nahuatl language, Teotihuacan translates to something like “the holy abode of the gods.” It covers 21 square kilometers (8 mi2) and features assorted structures, including residential areas and mighty pyramid temples comparable to those built by the Egyptians. In its heyday between 100 BC and AD 700, its population boomed, with estimates ranging from 25,000 to a more ambitious 200,000.

The pyramids of Teotihuacan still clutch their secrets tightly, but archaeologists hope that they’ve nosed their way to a royal tomb and possibly the remains of some important figure. Previously, the tomb turned up a grab bag of ritual relics, including mammoth seashells, jaguar remains, and oddly enough, a collection of small rubber and metal spheres, nicknamed “disco balls.”

The river of mercury gurgles within a tunnel beneath the pyramid, possibly as an otherworldly seal concealing a burial chamber. Whatever lurks on the other side might finally teach us something substantial about the pre-Aztec Teotihuacan-builders, a culture that left no record of itself or its customs.

Archaeologists can’t even determine how or by whom the city was ruled. With no palaces or regal murals anywhere to be found, it’s unclear if the civilization was under a single sovereign, a small cadre of regional leaders, or a decentralized kingship composed of priests or high-ranking militarists.

7 Japanese Tumuli And Haniwa

The Egyptians entombed their dead with a variety of items such as chairs and drinking vessels because Crate & Barrel doesn’t exist in the afterlife. Several thousand years later, a somewhat similar tradition emerged in Japan. Between AD 250 and 552, a span known as the Tumulus period, the Japanese piled large earthen mounds, or tumuli, atop burial sites.

The largest tumulus, Daisenryo Kofun, resides in Sakai City and (probably) belongs to Japan’s 16th emperor, Nintoku. The tomb is an impressive 486 meters (1,594 ft) long and 35 meters (115 ft) high. The broccoli-green keyhole looks unreal amid its densely populated surroundings. And, like all kofun worth their salt, it’s protected by an imposing moat.

The holy men who interred the body also supplied numerous unglazed terra-cotta sculptures called haniwa. The oldest, crudest haniwa lacked features and simply demarcated burial boundaries. Over hundreds of years, the haniwa evolved, taking the forms of attendants, military equipment, houses, or whatever else the deceased might need in the otherworldly realm. The haniwa, some as tall as their earthly counterparts, stood upright to mark the burial mound, tombstone-style.

6 The Holy Thorn Reliquary

After Christ’s crucifixion, the famed Crown of Thorns found its way into the possession of King Louis IX of France. Louis integrated the Crown as a symbol of the royal French lineage and erected a Gothic-style chapel in Paris, the Sainte-Chappelle, to display it along with his many Christian relics.

In the eyes of the public, Louis’s sacred collection made him the “holiest” man in Europe and the premier of western Christianity. So, what did Louis do after being entrusted (by himself) with one of Christianity’s most invaluable devices? He did what any King would do: He snipped off the thorns and affixed them to the French royal family’s line of jewelry.

One of these bejewled pieces is known as the Holy Thorn Reliquary, an ornate, gilded representation of the Last Judgment. The golden scene is encrusted with pearls, rubies, and sapphires. Louis believed, and possibly feared, that Christ should reclaim the thorns during the Second Coming, and we can’t imagine he’d be too happy to see his earthly adornment transfigured into regal bling. The reliquary’s subject matter (the Last Judgment) was chosen at least partially to appease the re-reincarnated Son of God.

5 Saint Paul’s Supposed Sarcophagus In Rome

Saint Paul, the apostle formerly known as Saul of Tarsus, extolled the virtues of Christianity more relentlessly than anyone save Big J himself. Upon being martyred, Paul and Saint Peter were buried along Rome’s famous continental bloodline, the Via Appia.

Then, to reward his unabated work ethic in leading the first generation of Christians, his remains were transferred to one of Rome’s four original papal basilicas, the eponymous church of St. Paul Outside the Walls. According to legend, St. Paul reposes within a sarcophagus below the basilica’s main altar.

In a somewhat surprising decision, the church opted to have the potential remains tested for holiness. Beneath the altar, researchers indeed found a sarcophagus and drilled a small hole into its supposedly 2,000-year-old shell. Inside, they found gilded purple linen, ancient grains of incense, and bone fragments. Carbon-14 ratios confirmed that the remains were from the first or second century, supporting the claimed timeline. To celebrate, Pope Benedict XVI announced the confirmation in a speech given from the very same basilica in 2009 as a prelude to the Feasts of Saint Peter and Saint Paul.

4 Siberian Death Masks

Ancient Siberian cultures venerated the dead with a variety of creepy (to us) funerary rites. One common practice was burning and then recreating the deceased in effigy. An excavation in the Siberian Kemerovo region turned up a sizable, 40-square-meter (430 ft2) crypt populated by 30 adult corpses adorned with realistic death masks hewn of gypsum, a soft sandy mineral used as plaster.

That’s the least unsettling part of the procedure. The bodies within the Shestakovo-3 tomb received a full ritual treatment. First, they were cremated. Then, the larger bones that stubbornly remained intact were stuffed inside leather or fabric dummies. Finally, masks sculpted in the likeness of the deceased were applied to the dummies. Ceremonial feasts may have been held afterward, before the crypt, covered with logs, was set aflame. Younger bones were found as well, though the children did not don masks and were buried outside the crypt walls.

In a similar find, archaeologists at Zeleniy Yar, located on the Siberian fringes of the Arctic Circle, uncovered 34 copper-masked corpses. In a gruesome twist, their skulls were smashed in, possibly to prevent their ever-living souls from wreaking havoc upon the living. Preservation-wise, the bodies fared better than the ones at Kemerovo, due to the permafrost and the antioxidative properties of the copper masks.

3 Buddhist ‘Human Pearls’

In most religions, displaying the remains of saintly figures is a time-honored tradition. Buddhists are no different and tediously collect the leftovers after the cremation of prominent ascetics, or bhikkhu.

After the ritual burning of the body, followers sift through ashes and charred tissue for the crystalline residues left behind by a vaporized corpse. Sarira, or (more disturbingly) “human pearls,” are super-sacred relics exhibited in ornate, well-protected displays for throngs of gawking devotees. Through piety, Buddhist monastics accumulate merit, or good mojo, and these remains are believed to be the distilled, physical manifestation of a monk’s devotion.

Some of these remains indeed resemble pearls, though shape, consistency, and color are dependent on the bodily source. A torched liver, for example, precipitates yellowish seed-like sarira not unlike mustard seeds.

The most prized remnants (thought some do not define these as sarira) come from Siddhartha Gautama himself. In Singapore’s Chinatown, a large temple was erected to house Shakyamuni’s supposed tooth—the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple and Museum. But the Buddha had plenty of teeth to go around, and the Sri Lankan town of Kandy also features a vibrant temple, or wat, built around a Buddha tooth—the Temple of the Tooth.

2 Egyptian Death Boat

To gain entrance to the party known as the afterlife, a dead Egyptian must brave a couple tasks. First, their heart is weighed against the feather of Ma’at, or universal truth. A panel of divine judges, under the auspices of Anubis and Osiris, then decide the deceased’s postmortal destiny. If that’s not stressful enough, the dead must also metaphysically cross the River Nile for their slice of eternal life.

To help one along his or her journey, relatives and priests interred a variety of amenities along with the deceased, including essentials like beer jars. However, the dead will forever remain stranded on the wrong side of the Nile without a proper vessel. So, beginning in the Early Dynastic Period, around 5,000 years ago, privileged Egyptian corpses were supplied funerary boats, ranging in size and sophistication commensurate to one’s status.

Pharaohs and other VIPs commissioned giant, life-size funerary boats. The oldest specimen dates to 2950 BC and was originally mistaken for a wooden floor. Realizing that Egyptian tombs usually lack wooden flooring, a later excavation recovered the ancient 6-meter-long (20 ft) boat full of bread molds and beer-making equipment.

The greatest of these river-faring vessels, the 44-meter-long (144 ft) Solar Barge of Khufu (aka Cheops), was unearthed under amazing circumstances in 1954. Archaeologists, seemingly at random, shoveled beneath a stone wall right next to Khufu’s Great Pyramid, the oldest and largest of the famed Egyptian trio. There, underneath still more layers of charcoal, wood chips, and a row of 40 limestone blocks, researchers found 1,244 puzzling pieces of fine Lebanese cedar. It took 20 months to carefully remove the pieces and more than 10 years to reassemble the barge like a 3-D puzzle. Amazingly, Egyptian shipbuilders used no nails, relying only on interlocking joints and ropes made of halfa grass.

1 Palmyrene Funerary Portraits

The Syrian city of Palmyra, formerly Tadmor, enjoyed a prosperous heyday as a Roman subject. The desert city’s economic peak occurred between the second and third centuries, when the continental trade routes from China to Rome were rerouted through Palmyra, creating a decadent confluence of Eastern and Western goodies.

Most notably, the affluent Palmyrenes gained fame for their beautiful funerary reliefs. For a short span of time between the first and third century AD, Roman-Syrians constructed grand towers to entomb the dead. Loculi, or burial holes, marked the interior walls of the tomb towers, with each sarcophagus capped with a sculpted portrait of the dead therein. These perfectly sculpted reliefs depicted the deceased as they lived, in their specific garb (including period-specific pantsuits) and holding the tools of their earthly trades. For example, a priest might don ceremonial headgear and clutch a bowl and jug, while the ubiquitous cloth-makers present a spindle and distaff.

Some images depict more intricate scenes, including ever-popular funeral feasts, a ritual inspired by the same Romans who oversaw Palmyra’s emergence as the most prominent Near East outpost during the early years of the second century AD. These breathtaking funerary forms were discontinued after less than a century, however, in favor of below-ground burials in crypts known as hypogeums.