Crime

Crime  Crime

Crime  Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

10 Fake Viral News Stories From The Early 20th Century

Getting something to go viral requires the right combination of luck, timing, and hitting what resonates most with an audience at that particular moment. In the first half of the 20th century, the world saw its share of viral stories that spread through newspapers and journals. Unfortunately, not all of them were true.

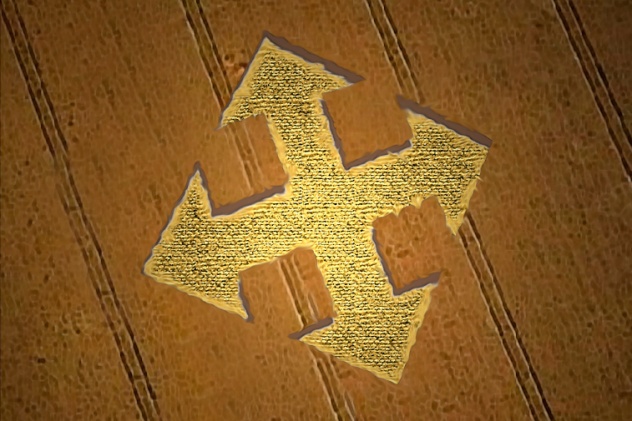

10 Nazi Crop Circles

Life on the home front in the United States during World War II was understandably terrifying. No one knew for sure whether the Germans would be planning an attack, so when mysterious symbols started popping up across the East Coast, people were worried.

Newspapers didn’t help, especially when they started to run photos of the crop circles and other mysterious symbols that were being found in farmland. Hay bales were being stacked in such a way that they seemed to point toward high-profile targets and cities. Sacks of grain were dumped in peculiar patterns that seemed to indicate the direction of a nearby military base. Arrows and other directional indicators were being plowed into fields and crops. One photo showed bags of fertilizer that seemed to form the number “9,” and the story that went with the photo claimed that the tail of the number pointed toward a nearby factory that was manufacturing planes, presumably for the war effort.

The stories did more than just frighten people; they created serious discord between neighbors. The field of one farmer, whose family had been in the area for generations, was clearly identifiable as the one with the mysterious “9,” and if there’s one thing people won’t stand for, it’s a double agent living nearby.

It wasn’t long before the War Department caught wind of the reports and stepped in to defuse what might have become an unnecessarily volatile situation. There were rational explanations for everything: The sacks of fertilizer had been simply thrown off the back of a truck and left to dry in the sun, forming an accidental pattern that definitely didn’t point to any military factory. (There were none in the area.) The arrows were plowed into the fields by a Fish and Game warden in the process of creating feeding grounds for birds.

Similar things were happening in England, too. MI5 investigated and found that they, too, were harmless coincidences blown out of proportion by people on the lookout for anything out of the ordinary. Those investigations didn’t have the same viral spread that the US ones did, though, and were kept fairly quiet.

9 Daisy Alexander’s Will

In 1949, a story ran that gave hope to countless people: Jack Wurm, a man who lived day by day, worked in a kitchen, and rented the house that he shared with his wife, was walking along a San Francisco beach when he saw a bottle that had washed up on shore. There was a piece of paper inside, which read, “To avoid all confusion I leave my entire estate to the lucky person who finds this bottle and to my attorney, Barry Cohen, share and share alike. Daisy Alexander—June 20, 1937.”

Wurm put it aside, thinking it was nothing but a joke. A few months later, he was at a party with some friends who had just returned from military service in Britain. One recognized the name. Daisy Alexander was the daughter of Isaac Singer of Singer Sewing Machine fame. And she’d just died from injuries sustained in the bombing of London. She’d left behind a $12 million fortune, but no one had been able to find the will that they knew she’d written.

Wurm got in touch with a lawyer, who found that everything was legit. Wurm and Cohen would inherit $6 million each. The story went viral, featuring in newspapers across the country as well as countless religious sermons as a cautionary tale of how you shouldn’t discount anything, no matter how unbelievable and fantastic it may seem.

The real story might have been even more bizarre and unlikely: Singer really did have a daughter nicknamed Daisy, and according to The London Times, she died peacefully on September 20, 1939. Barry Cohen really was her lawyer, and her will truly was lost. A search of her estate turned up nothing, and Cohen even tried consulting with a clairvoyant and tracking down Daisy’s parrot to see if the bird would recite anything useful. Nothing worked.

Cohen examined the document that Wurm claimed to have found and ultimately announced that it was a fake. No one was sure who faked it, as everyone involved claimed that Wurm himself was the last person to try something like that. The most likely suspect might be the military friend who had told him about Daisy’s identity in the first place.

The estate was finally settled based on an earlier 1909 will that left everything to Daisy’s niece and nephew. Wurm died in 1987, without the money.

8 Fritz Kreisler’s Compositions

Fritz Kreisler was a violinist who performed in Europe during the 1910s. At a concert in Vienna, he had what the audience viewed as the audacity to include a few of his own compositions in a performance. He was attacked by critics for putting his work on par with the classic masters, and Kreisler didn’t argue—not directly, at least.

Not long after, the violinist revealed that he’d been sifting through the documents of a remote monastery when he came across a collection of pieces that had been written by masters such as Vivaldi. There was an entire collection of works, and Kreisler convinced the monks to sell him the whole lot. He arranged these forgotten works and put them back on stage where they belonged, and the critics loved him for it. Kreisler, credited as the arranger and editor of the 25 pieces that he claimed to have bought, was lauded as someone who had saved now-treasured pieces of classical music from obscurity and likely destruction.

It wasn’t until his 60th birthday—in 1935—that he confessed when someone finally asked him to tell the truth about the pieces. There was never any collection of music, there was never any remote monastery, and the pieces that so many fans, critics, and professionals alike had come to love were written by Kreisler himself.

Kreisler later claimed in an interview that part of the reason he’d done it was simply because he didn’t want to be known as a composer, but the lack of music written strictly for the violin had left him despairing. Unable to hire other musicians to accompany him when he was starting out and trying to make a name for himself, he decided to find some of the most obscure composers of the 17th and 18th century he could and “discover” some of their lost works. It would give him credibility, and he would get the music he wanted to play without being labeled a composer.

7 The Old Librarian’s Almanack

Edmund Lester Pearson wrote a weekly column for The Boston Evening Transcript as “The Librarian.” The column was so ridiculously popular that it lasted from 1906 to 1920. It was filled with humorous anecdotes about libraries and librarians, and it’s still heralded as a reference for the history of libraries throughout those two decades.

In 1908, Pearson made a reference to a book called The Old Librarian’s Almanack, and a few months later, a friend, who conveniently owned Elm Tree Press, suggested that it should be a real book. So they headed to the Connecticut Historical Library, picked out an almanac from 1773, and started writing. They updated the book’s astronomical details to “predict” everything that was going to happen in 1774, and Pearson raided his own column for bits of wisdom to be included in the almanac, making it the source. They invented a writer, too—a lifelong bachelor named Jared Bean, who wrote anecdotes that presumably would have been hilarious to librarians in 1773.

When the almanac finally went to print, they made sure that they gotten the look just right. Everyone who was in on it figured that readers would realize that it was a tongue-in-cheek version of what was then a hugely popular format for books. That didn’t happen.

New York’s The Sun was the first to run a story on the discovery of an amazing, old, rare book, and it was left to Pearson to thank them for noticing that he’d republished the source for all his witty librarian remarks. While The Sun eventually figured out that was a joke (and good-naturedly ran a biographical piece on the fictional Bean), papers across the country started to pick up the story of the reprint of a rare book. One, The Hartford Daily Courant, even named Bean as “the father of the almanac humorists.” From there, literary organizations started to take notice, and the almanac made it into their journals.

This widespread coverage was pretty impressive, considering that the almanac was filled with wisdom such as that assigned to June 30: That day, the almanac informed the librarian which people shouldn’t be allowed into the library—politicians, necromancers, the light-witted, the senile, anyone with an infectious disease, and fanatic preachers. As for women, it said, “Be suspicious of Women. They are given to the Reading of frivolous Romances.”

The hoax wasn’t widely revealed until 1910, when the journal America finally linked Pearson with the not-so-serious text as well as an article written by the founder of Elm Tree Press that derided people who reviewed and lauded books without actually reading them.

6 The Dissolving Bathing Suit

According to a story that ran in the newspapers of 1920s France, a British millionaire vacationing on the French Riviera had found an ingenious use for a new fabric that dissolved in saltwater. He made bathing suits from the material and handed them out to the women attending a party at his house. Hilarity ensued when he suggested that everyone hop into the Mediterranean for a swim.

After the story ran, the newspaper’s editor asked the reporter for a sample of the fabric. That finally prompted the reporter to do some serious fact-checking, and he found out that the story was, of course, fake. However, he told his editor that they couldn’t ship the fabric because of the salty, humid air, and he was told to have the sample sealed in an airtight and watertight tin box. He filled a box with ground cereal, shipped that, and convinced everyone that the fabric couldn’t be sent overseas.

At least, that was the version of events as reported in the memoir of Webb Miller, a US war reporter. The truth is less easy to pinpoint, but there were many newspaper articles that claimed that the French had developed a dissolving bathing suit. The first stories ran in 1930, with wire services falling for it again in 1935, with the inventor now being named as “Miss Cassie Moss.”

By the 1960s, the story had evolved. Now, it was a French designer who had wanted to design a handy way for women to retain their modesty on their way to the water when they decided to go for a nude night swim. Later, the story would be picked up by Weekly World News, the same tabloid known for creating BatBoy, in both 1994 and 2004.

5 The Horn Papers

The Horn Papers are a set of fraudulent genealogical documents and family heirlooms that began their bizarre saga in 1932. That’s when a couple of newspaper editors got a letter from W.F. Horn of Topeka, Kansas. According to Horn, he had found some treasures buried in his family’s home, including documents from the first court proceedings west of the Alleghenies as well as period maps. He also had diaries, journals, and artifacts that seemed to date from the earliest settlements in Western Pennsylvania, and among those documents were some key pieces that were recorded nowhere else.

While Horn had the original documents, he claimed that they were too fragile to share, and he could only publicize the handwritten copies that he’d made himself. That probably should have been the first clue that something was up. Nevertheless, the newspapers started running his information a little bit at a time in a weekly feature. The feature became so popular that when Horn showed up in Pennsylvania, he immediately went on speaking tours and lecture circuits across the East Coast.

Horn was able to recite his history flawlessly and deflected the occasional question about the papers’ authenticity with ease. There were certainly doubts, as Horn’s papers talked not only about family history, but also about some rather major events, like the Battle of Flint Top in 1748 and the massacre of 12,000 people. The fact that there was no other record of the battle (or of the history book that Horn cited, called Andrea’s History of Northwest Virginia) should have raised some more questions, but when Horn’s papers directed scholars to two lead plates from the 18th century, it seemed a sure thing, even though the dates referenced didn’t match those on the plates.

The University of Pennsylvania turned down the chance to authenticate the materials, so the task fell to the Greene County Historical Society. At the end, they were so convinced of their authenticity that they raised and spent $20,000 to buy the entire collection.

The society proudly published the documents, hoping to rewrite, or at least complete, the history of their region. That’s when they got the attention of Princeton scholars and the American Historical Association, and that’s when the whole thing started to fall apart. The ink was dated to around 1930. The coins that Horn showed on his tours bore the letters “COV,” but so did every other Dutch coin that had nothing to do with the “Colony of Virginia.” The wrong calendar had been used for the dates. As for the lead plates, they had a high nickel content, which meant that they came from somewhere around Missouri.

Horn himself died in 1956. By that time, he was described as “no longer interested” in his papers.

4 The Chesterfield Lepers

It only takes one rumor to destroy a company’s reputation, and in 1934, Chesterfield became the target of a rumor as destructive as it was both unlikely and horrifying.

The rumor held that the company’s cigarette manufacturing plant in Richmond, Virginia, was employing lepers to work in their factory. People couldn’t switch to another brand fast enough, and even official statements from Richmond’s mayor—saying that he had personally inspected the factory and there were no lepers there—didn’t help. For the next 10 years, Chesterfield focused their marketing campaign on convincing the world that they had the cleanest, most state-of-the-art equipment that money could buy . . . and definitely no lepers.

Chesterfield never found out where the rumor came from, despite offering a $25,000 reward. Whoever had started the rumor that swept across the country with disastrous consequences for the company wasn’t even the first to come up with it. In 1882, a Pennsylvania newspaper appropriately named The Chester Times published a warning that lepers were well-known to be frequently employed in shops that made both cigars and cigarettes. The article came complete with a warning from doctors that anyone who touched something that was touched by a leper’s fingers would contract the dreaded disease.

In the 1940s, the rumor also became associated with another cigarette manufacturer called Spud. It’s still claimed that Spud went out of business as a result. (It was actually absorbed by Philip Morris.) Later, soldiers overseas in Vietnam were warned against smoking joints because they were licked by lepers.

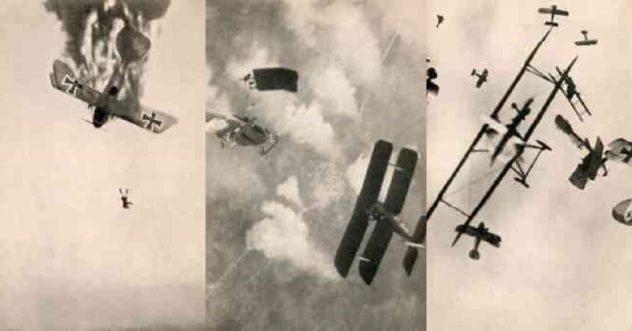

3 The Fake World War I Photos

If you’ve seen any photos from World War I depicting aerial dogfights, there were probably pictures credited to an American RAF serviceman named Wesley David Archer. They were originally published in a book called Death in the Air: The War Diary and Photographs of a Flying Corps Pilot. Published in 1933, the photos were considered incredibly rare and authentic photos of life in the air. And they were terrifying. Planes billowed smoke and chased each other across the skies. In some, pilots were shown plummeting to their inevitable death.

Archer claimed that he got the photos by rigging a machine gun trigger to take photographs of whatever was in its sights. His name originally wasn’t even associated with the book or the photos because he’d broken a whole bunch of military rules in order to get them. After the war, the pictures came into the possession of a woman named Gladys Maud Cockburn-Lange, who sold them for $20,000.

After their release, the photos showed up everywhere from textbooks to museums. According to the Smithsonian, people still ask for permission to use the photos in various projects today, although they’ve been known to be fakes since the mid-1980s.

When the Society of World War I Aero Historians started digging, they found that while Archer did serve some military time in Britain, he went home in 1920. When he left the military, he went into the film industry to work as a set-maker. He was a model-maker, too, and practiced his skills staging the now-famous dogfight photos.

And as for Gladys Maud Cockburn-Lange? She was his wife.

2 The Fake Baldness Epidemics

If you were a man in 1926 and you were the least bit worried about the state of your hair (specifically the possibility you might be going bald), the headlines that hit papers across the country would have had you steering clear of Pennsylvania.

It was reported that more than 300 young men between the ages of 19 and 30 were suddenly going bald in the Pennsylvania town of Kittanning. They were seeing doctors in the hopes of figuring out what was making them lose their hair, but the doctors were baffled. They were only able to give advice like recommending not wearing tight hats and, bizarrely, only getting haircuts during the first quarter phase of the Moon.

The reports weren’t exactly a hoax; they were something small blown way out of proportion. A number of men really did suffer sudden hair loss in Kittanning, but there were only about a dozen of them. The response to the story was so far-reaching that the powers that be in Kittanning were forced to release a statement saying that the men of their town were not all going bald. Of particular concern was the sheer number of hair tonic salesmen and peddlers of quack baldness cures who descended on the town, a force that the town leaders called “hordes.”

That’s not the only time that newspapers have reported massive outbreaks of baldness. In 1901, The Spectator reported that men and women alike in Japan were being stricken by baldness. The rather dramatic lead stated, “Japan must live in a state of constant dread, for, according to reports from that country, they may at any time lose that greatly valued possession, the hair.” The story described not only bald patches on the head, but also men who lost half their beards or part of a mustache. Fortunately, an investigation by the US Marine Hospital Service found that it was simply nothing more than alarmist journalism.

1 Ern Malley

Ern Malley was born in 1918. After the death of his father, he was sent to live in Australia with his sister, Ethel. The rest of his story is heartbreaking: His mother also died, so he dropped out of school, worked a series of jobs, drifted from city to city, and died in 1943. He also wrote poetry. He was a genius who was never recognized in life and a tragic figure taken too young. That poetry was the vision of a man faced with his own mortality, a broken hero and everyman who spoke to people’s very souls.

Malley’s work went largely undiscovered until it was submitted to a literary journal called Angry Penguins. Editor Max Harris dedicated an entire issue to the literary star that he’d uncovered, much to his ultimate dismay. First, the police got involved on the pretense that Malley’s works were obscene, and Harris found himself in court defending the poet’s work. The court case didn’t go the way the police had planned, especially when the detective in charge was asked the definition of some supposedly lewd words and didn’t know what they meant. That incident elevated Malley to the international stage, but Harris would be doubly embarrassed when he found out that Malley wasn’t a real person.

Malley was the creation of Corporal Harold Stewart and Lieutenant James McAuley. Both were from working-class families and had studied at Sydney University, at the same time that fellow student Max Harris was setting out to change the face of popular poetry forever. He was at the head of what McAuley and Stewart saw as the death of poetry as it should be, so they sat down one afternoon and created not only Malley, but his entire catalog of work. They used books for reference, and the opening lines of one of the works were pulled from a manual on draining mosquito breeding grounds.

They set out to create something that was deliberately bad, trying to demonstrate just how far poetry had fallen. Instead, even after they’d come clean and confessed to the hoax, praise for what they created continued to roll in. They’re still diagrammed by critics and heralded by others, and neither of them have laid claim to any of the money made by Malley’s works.