History

History  History

History  Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Crime

Crime 10 Dark Details of the “Bodies in the Barrels” Murders

Animals

Animals The Animal Kingdom’s 10 Greatest Dance Moves

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Box Office Bombs That We Should Have Predicted in 2025

History

History 10 Extreme Laws That Tried to Engineer Society

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

10 Bizarre Customs For Entering The Afterlife

Different cultures and religions have distinct beliefs about life after death, but most of them believe in some sort of afterlife. While most religions agree that another world exists beyond this one, they generally hold very different views on many of its aspects, such as its location, availability, and perhaps most importantly, the best way to successfully reach it. Below we have a list of 10 historical funerary customs that supposedly aided the deceased in successfully reaching the afterlife.

10 Corpse Roads

During the Middle Ages, churches were very protective of their parish members. When a member of the parish passed away, the church was determined to have them buried in the proper church graveyard. This was because it was considered the right thing to do and also because it meant that the church would receive money for the burial ceremony.

Communities, however, were becoming more and more spread out, which meant that the local parish church could be miles away, making it difficult to transport a body from the village to the church graveyard. As a result, the idea of a corpse road, a road that connected a village to the cemetery, was born. Corpse roads were also known as coffin roads, church ways, or burial roads and often passed through desolate places that were difficult to navigate. This was partly due to landowners being against corpse roads becoming standard routes for trade and travel and partly due to the belief that spirits could only travel in straight lines. Thus, meandering roads, labyrinths, and crossroads ensured that the spirit of the deceased could not return to haunt its previous dwelling. It was also believed that spirits could not pass through water, and as a result, many corpse roads had a river streaming through them. Carrying the corpse with its feet facing away from the direction of its home was also a superstition that was thoroughly followed to ensure that the spirit would not return.

Today, many of these roads have disappeared into history. A few, however, still remain in the UK and the Netherlands. You can recognize them by their name and various landmarks, such as crosses, lych gates, and coffin stones (a stone used for resting the coffin when its carriers needed a rest, as it was inadvisable to allow the spirit to meet the ground) that are scattered throughout these roads. And if you notice a corpse candle floating around, you’ll know you’re definitely on the right road.

9 Coffin Portraits

The term “coffin portrait” refers to a trend that was popular in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 17th and 18th centuries, whereby an extremely realistic portrait of the deceased was placed on the coffin for the funeral but was removed before the burial. It was important that these coffin portraits were realistic, as their intention was to create the impression that the deceased was attending his or her funeral. Thus, the deceased was often portrayed standing immobile along the central axis of the portrait, with the face turned slightly sideways and the eyes looking directly at those present. Coffin portraits also represented the timelessness of the spiritual body, which was going to rise in the general resurrection at the Last Judgement, as opposed to the natural body, which was about to be buried.

The quality of coffin paintings varied depending on the wealth of the deceased since they could be drawn on a large range of metals, such as tin, copper, or lead. As such, their price ranged from the affordable to the luxurious.

However, these rather bizarre portraits were not purely a 17th-century invention. Coffin portraits go back as far as ancient Egypt, where they were known as mummy portraits or more commonly, Fayum portraits (due to their popularity in the Fayum Basin). Fayum portraits date back to the Greek and Roman occupation of Egypt, a time when the burial habits of the Egyptians underwent minor changes in order to incorporate these rather strange funerary portraits. The exact purpose of Fayum portraits is unknown, but it’s possible that they were used in a similar way to the carved wooden masks which were placed over the deceased person’s head—to identify the owner of the mask or the portrait in the afterlife.

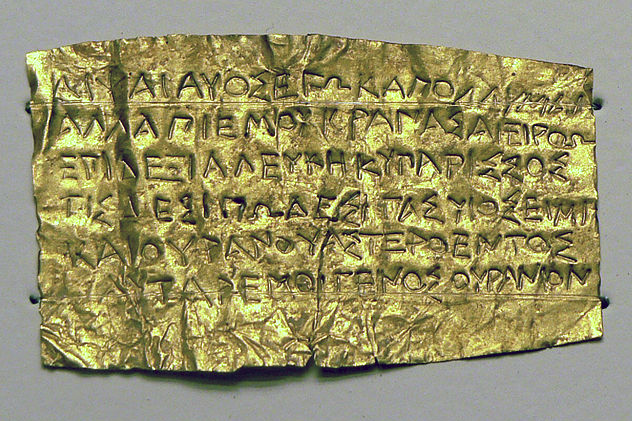

8 Totenpass

Totenpass, or “passport of the dead,” refers to small inscribed tablets or metal leaves that were found buried with those thought to have been of Orphic, Dionysiac, and some ancient Egyptian and Semitic religions. The gold inscriptions on the tablets or leaves instructed the deceased on how to navigate the afterlife and included directions for avoiding hazards as well as the responses one should provide to the underworld judges. The Totenpass was often placed in the hands of the deceased, but this was only the case when the tablet wasn’t folded into a capsule. If the tablet was folded, it was usually worn around the neck as an amulet or placed inside the deceased person’s mouth.

The best-known example of a Totenpass are the so-called Orphic gold tablets. The term “Orphic” refers to the Orphic religion or mystery cult that was supposedly popular among the ancient Greeks and Thracians and which involved performing secret rites and sharing hidden knowledge of the afterlife. Only a limited number of these tablets have been found, which confirms the belief that they were used by a minority group. Nevertheless, the geographical area in which these tablets were discovered is quite large, stretching from Macedonia to the Greek islands to Rome. They also differ in date: Almost 600 years stretches between the oldest and the most recent tablets.

7 Kkoktu

Kktoktu is the word used for describing small, brightly painted Korean funeral dolls made out of wood, which were used for adorning coffins. They depicted people, animals, and mythical creatures, and unlike most somber and morbid funerary art, they were festive and eye-catching. Moreover, their use wasn’t restricted to aristocrats; ordinary people used them just as much as those who came from wealthy families. While the gaiety of kkoktu may seem not at all appropriate in times of mourning, they show the desire of the culture to have their loved ones pass onto the next world surrounded by care and joy.

These festively painted figurines of animals and people were often fitted onto a bier (a movable frame used for carrying the coffin or the corpse to the grave) for the purpose of keeping company and guiding the deceased when entering the next world. Even when kkoktu were shaped in human form, they were not considered human, but rather intermediaries between the material and supernatural worlds.

Kkoktu came in various shapes and forms, the most common being the guide, the guard, the caregiver, and the entertainer. The guide is portrayed as riding an animal; he leads the soul of the deceased into the other world. The guard is often portrayed as a warrior or an army officer whose task is to protect the soul from evil spirits. The caregiver usually takes on the form of a woman and provides medical care to the deceased as if they were still alive. Finally, the entertainer is often depicted as a clown or an acrobat, consoling the deceased and distracting the mourners from their grief. Figurines such as phoenixes, dragons, and goblins were also popular and symbolized the freedom of the soul.

6 Charon’s Obols Or Danake

“Charon’s obol” refers to coins that were supposedly used by the ancient Greeks as payment for Charon, the ferryman of Hades. According to Greek mythology, Charon was the boatman of the underworld who was responsible for ferrying the souls of the deceased across the River Acheron (according to Greek texts) or the River Styx (according to Latin texts). Those who wanted to be transported to the other world had to pay an obol, and those who could not pay were condemned to wander along the riverbank, haunting the living world as ghosts.

The term “obol” originally referred to a small, silver ancient Greek coin. However, after the Greek-speaking cities of the Mediterranean were absorbed into the Roman empire, the term came to mean any bronze coin of low value. In addition to obols, other coin-like objects, known as danake (an old Persian synonym for obol), have appeared in excavation reports and the antiquities market. Danake are described as uniface because the design appears only on one side of the coin. One such danake coin depicts a honeybee, perhaps expressing the wish for a sweet afterlife.

Only a small number of ancient Greek graves actually contain any coins within them. Furthermore, the placement of these coins was not solely restricted to the mouth of the deceased. In fact, Charon’s obols have also been found in or near the hands of the deceased, at their feet, or scattered in the grave. In areas where cremation was the usual funerary practice, burned coins were sometimes found with the ashes in the urn. Various other explanations for Charon’s obols have been provided by scholars, such as the idea that the coins were used for paying off the deceased to prevent their return to the living world or that the coins were used by the deceased in the afterlife to maintain their status in the underworld.

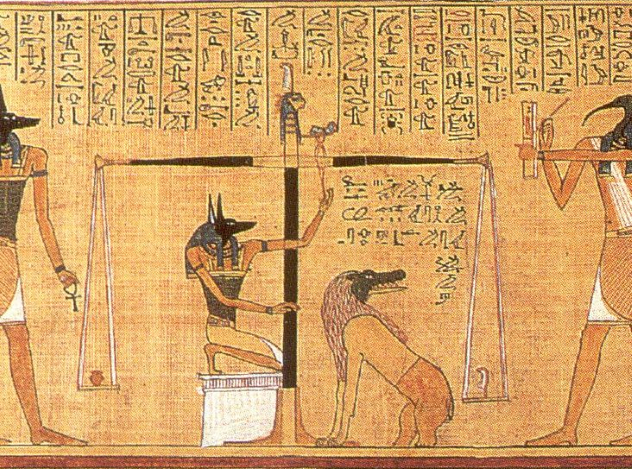

5 The Book Of The Dead

The Egyptian Book of the Dead was known to Egyptians as The Book of Coming Forth by Day or Spells for Going Forth by Day. It was a collection of chapters made up of magic spells and formulas intended to help the deceased find and navigate the afterlife. The Egyptians believed that afterlife was a continuation of life on Earth and that after the deceased had passed all the challenges and the judgements in the Hall of Truth, they would be allowed to enter paradise, which would reflect their lives on Earth. However, to obtain permission to enter paradise, a person needed to know where to go, how to address the gods, and what to say at certain times. This was where the Book of the Dead came in handy.

The earliest known version of the Book of the Dead is known to have partly incorporated two previous collections of Egyptian religious literature—the Coffin Texts and the Pyramid Texts. In time, both of these texts were replaced by the Book of the Dead, which eventually became extremely popular among Egyptians of all social classes by the time of the New Kingdom (which lasted between the 16th and 11th centuries BC).

Scribes who were experts in spells were often commissioned to create custom-made books for an individual or a family. In order to summarize the type of journey and the obstacles that a person might come across after death, the scribe had to know the type of life the person requesting the book had lived so that specific spells and instructions could be created. People could request as little or as many spells as they could afford. The number of spells and the type of illustrations included depended on the person’s financial resources, as did the quality of the papyrus used.

The most popular spell of the Book of the Dead was Spell 125. Spell 125 described the judgement of the heart of the deceased in the Hall of Truth and advised the deceased on what should be said when facing the gods. However, other incredibly specific information was required, including knowledge of the different gods’ names and their responsibilities, the names of the doors in the room and the floor the deceased had to walk on, as well as the names of one’s own feet. The spell ended with advice as to what the soul should be wearing when it met the judgement of the gods and the way that the spell should be recited. If all went well and the deceased person’s heart was lighter than the Feather of Truth, they would be allowed to enjoy eternal paradise, where they would be reconnected with loved ones and even pets.

4 Kulap

Kulap were limestone or chalk figures that were once an important funerary ritual in Southern New Ireland in Papua New Guinea. These figures were used to commemorate the deceased and were produced by specialists from the Punam region of the Rossel Mountains, where limestone quarries were located.

Kulap figures served as a temporary dwelling place on Earth for the deceased, preventing the dead person’s spirit from wandering around the village, causing mischief and harm to the living. Thus, whenever a man or a woman from a wealthy family died, a male relative of the family would make a journey to the Rossel Mountains, where he would acquire either a male or female kulap, depending on the gender of the deceased. Once back home, the relative would present the kulap to the local leader, who would then place it in a memorial shrine alongside other kulap. Only men were allowed inside the memorial shrine to view the kulap and to perform honorary dances. However, women often gathered outside to mourn their dead relatives.

When the funerary ceremony was concluded and the kulap figure was no longer needed, it was removed from the shrine and smashed, releasing the soul of the deceased toward its journey into the afterlife. Kulap figures were eventually abandoned upon the adoption of Christianity in Southern New Ireland in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

3 Amatl

During the heyday of the Aztec culture, when an Aztec of low or medium status died, masters of burial ceremonies were called in to perform funerary rites and prepare the body for the afterlife. These ceremonies included pouring water over the deceased person’s head as well as dressing the body according to the deceased person’s condition, fortune, or circumstances of death. For example, if the deceased had died from overindulgence in alcohol, he or she was dressed with the emblems of Tezcatzoncatl, the god of wine and drunkards. A vase of water was then placed beside the corpse to satisfy his or her thirst during the journey to the afterlife.

One of the most significant rites, however, was the covering of the deceased in paper made of tree bark, known as amatl (also referred to as amate). The use of this specific paper was then explained to the deceased by the presiding funeral officials: The first piece of amatl paper was used to pass safely through two contending mountains. The second piece helped the deceased to travel without any danger on the road guarded by the Great Serpent. The third piece allowed a safe crossing over the Great Crocodile’s domain. The fourth piece was a passport, which allowed the deceased to cross the Seven Deserts. The fifth piece was used for a safe passage through the Eight Hills. Finally and perhaps most importantly, the sixth piece was used for defense against the north wind. In addition, for this latter challenge, the Aztecs burned the clothes and arms of the deceased so that the warmth coming from the burning body might protect the soul from the cold northern wind.

Killing a Techichi dog was also an important part of the ritual because it was believed that the dog would accompany the deceased on the journey to the other world. A cord was put around the dog’s neck so that it would be able to cross the deep river of the Nine Waters. The dog was usually either burned or buried alongside the deceased. If the body of the deceased was burned, its ashes were collected in a vase, and a green jewel was placed at the bottom to serve as a heart for the soul in the other world that it would soon inhabit.

2 Funerary Amulets

The ancient Egyptians believed that amulets had magical powers of protection and brought good fortune to their wearers. They wore amulets around their neck, wrists, fingers, and ankles from a very young age. However, amulets were as important in death as they were in life.

Hundreds of amulets were available for funerary use, but ultimately, the choice depended on the deceased person’s wealth and individual preference. The selected amulets were carefully placed on various parts of the mummy during the wrapping process. Some amulets could be placed anywhere; others had strict and predetermined positions. It was important that priests said prayers and performed rites as these amulets were placed.

The most popular amulet was the Heart Scarab, which was placed over the deceased person’s heart in order to protect it from being separated from the body in the underworld, as the heart was essential in the Weighing of the Heart Ceremony. Those who feared failing this test could recite the spell inscribed on the Heart Scarab to prevent their heart from betraying them. Another important amulet was the Amulet of the Ladder, which supposedly provided the deceased a safe passage from Earth to heaven. These amulets were often mentioned in the Book of the Dead.

Funerary amulets were also used in China in a similar way to those of ancient Egypt. During the Han period (202 BC–AD 220) and earlier, cicadas (a sacred animal symbol that represented rebirth and immortality) were immortalized as jade carvings, which were often called funeral jades, amulets of death, or tongue amulets. These jade carvings were placed on the tongue of the deceased and were supposed to induce resurrection by sympathetic magic.

1 Maize

The Maya believed that the world after death, also known as Xibalba (translated as “Place of Fright”), was a place of terror that had its own landscape, gods, and bloodthirsty predators. Interestingly, the Maya did not believe that it was truly possible to escape Xibalba, since mistakes and slip ups are part of human nature and thus completely unavoidable. Only those who died a violent death could truly avoid the Place of Terror.

In Mayan culture, the deceased were often buried with maize placed in their mouth, which served as nourishment for the soul’s difficult journey through the terrifying lands of Xibalba as well as a symbol of the soul’s rebirth. It’s not surprising that maize was the crop of choice in sustaining the soul through its otherworldly journey, since the Mayan diet consisted primarily of maize, squash, and beans. It’s believed that combined planting was common in ancient times, meaning that maize acted as a pole for the beans that twined around it, while the squash trailed along the ground in between.

In addition to maize, the mouth of the deceased was also often filled with one or more jade beads. Some believe that the jade beads were used as currency for the journey to Xibalba, while others argue that a single jade bead in the mouth of the deceased equaled an endless supply of maize.

A student from Ireland in love with books, writing, coffee, and cats.