History

History  History

History  Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

History

History 10 “Modern” Problems with Surprising Historical Analogs

Health

Health 10 Everyday Activities That Secretly Alter Consciousness

History

History Top 10 Historical Disasters Caused by Someone Calling in Sick

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Animals

Animals 10 New Shark Secrets That Recently Dropped

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Forgotten Realities of Early Live Television Broadcasts

Technology

Technology 10 Stopgap Technologies That Became Industry Standards

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wild Facts About Taxidermy That You Probably Didn’t Know

Travel

Travel 10 Beautiful Travel Destinations (That Will Kill You)

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Modern Marriage Rituals Born from Corporate Branding

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff Ten Bizarre Visions of 2026 from Fiction

10 Macabre Medical Experiments From History

Throughout history, some of the most important scientists have “bent the rules” every once in a while to achieve their goals. Always for the betterment of humanity as a whole, the suffering of a few to save the masses is always worth the risk—or is it?

Here are 10 examples that just might make you think twice about how you answer that question. The actions of some of these scientists may just cause you to wonder how many times our lives have really been gambled with over the centuries.

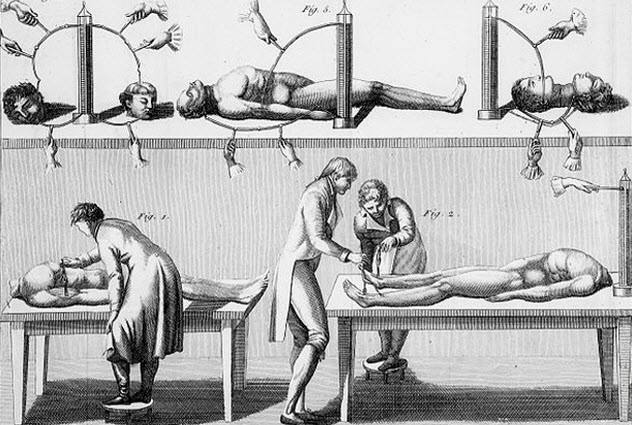

10 Giovanni Aldini

The Original ‘Doctor Frankenstein’

Giovanni Aldini (1762–1834) was a professor of physics at Bologna who had a scientific interest in a variety of fields. But the one that stands out most was galvanism. Aldini helped put together a group of scientists in Bologna to experiment in this area, which involves the therapeutic use of electrical currents.

This interest led him to create one of the most macabre road shows ever devised. Traveling all over Europe, Aldini choreographed countless gruesome theatrical displays. Crowds of patrons would pay to gather and gleefully stare in horror while the proverbial “mad scientist” electrified an assortment of grisly human and animal body parts. Aldini put on spectacular demonstrations, producing hair-raising spasmodic convulsions of arm and leg muscles and even more spine-tingling contractions of the facial muscles of dead human heads.

Using the severed remains of animals and humans and the current of a powerful battery, Aldini would cause eyes to roll, jaws to open, teeth to clack, and fleshy-smelling smoke to curl eerily into the electrically charged air. A truly appalling spectacle, witnesses were reported to say that they could not shake the feeling that the “victims” had really just been brought back to life only to suffer death again.

Always the showman, Aldini enjoyed his most famous performance in 1803 at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Using the corpse of an executed convict named George Forster, he proceeded to poke and prod the dead man with a pair of conducting rods connected to a battery, causing various parts of the corpse to quake, quiver, and contort.

In his day, he was not considered to be a “mad scientist” especially since the emperor of Austria, in recognition of his achievements, made Aldini a knight of the Iron Crown and councillor of state at Milan.

9 A Real Haitian Zombie And Zombie Poison

A worn, ragged-looking man shows up in a rural Haitian town claiming to have died on May 2, 1962. One of the problems with this picture is that the year was 1980. Clairvius Narcisse swore that he had been pronounced dead in Deschapelles, Haiti, at Albert Schweitzer Hospital. He also said that he was awake and conscious during the entire ordeal.

Narcisse also claimed that he had been completely paralyzed and could do nothing but lie there in horror as he was pronounced dead, nailed into a coffin, and unceremoniously buried alive. He also claimed that the bocor (Haitian witch doctor) who had made him a zombie had also dug him up and forced him to work as a zombie.

In Haiti, zombies are not only common in folklore but commonly feared as well. Scientists have uncovered innumerable reports of the bodies of friends and family members coming back to life. According to the legends, zombies are not aware of anything in their surroundings so they are generally harmless unless, of course, you allow them to regain their senses by eating salt.

Despite countless reports, investigators could locate little evidence either proving or disproving the phenomenon. A common theme with the zombie stories concerns people dying without receiving any medical care before their alleged deaths. This raises the red flags of fraud and possible mistaken identity for investigators to deal with.

Right about this time in the early 1980s, anthropologist and ethnobotanist Wade Davis just happened to be in Haiti to investigate the causes of zombies. Davis was there at the request of anesthesiologist Nathan Kline, who theorized that a drug was somehow involved and that it could have valuable medicinal uses. Davis was hoping to get his hands on samples of these zombie concoctions so that they could be chemically analyzed in the US for medicinal purposes.

Davis managed to gather eight samples of zombie powder from four different regions of the country. The ingredients in all of them were not the same, but seven of the eight had four ingredients in common. They were the neurotoxin tetrodotoxin (derived from puffer fish), the marine toad (also containing numerous toxic substances), the Hyla tree frog that secretes a very irritating but not lethal substance, some other ingredients derived from indigenous animals and plants, and even ground glass.

The use of puffer fish was the most intriguing to the scientists because the active ingredient tetrodotoxin causes both paralysis and death, and those poisoned with it are known to stay conscious right up until it occurs. The scientists theorized that the powder would create irritation if applied topically and subsequent scratching would break the skin of the victim and allow the tetrodotoxin to enter the bloodstream.

This would paralyze the victim and cause him to only appear to be dead. After the family buries the victim, the bocor returns and digs up the grave. If everything goes according to plan and the victim survives the horrific ordeal, the toxin would eventually wear off. Through the use of other debilitating drugs, the victim could come to truly believe that he had been turned into a zombie.

8 Poison Labs Of The Former Soviet Union

At one time, the former Soviet Union operated secret poison labs to experiment with new ways to covertly eliminate subversives and enemies of the state. The most infamous of these was a laboratory known as the Kamera (“Chamber”) where Russian scientists conducted experiments to look for better methods of poisoning people. Everyone knows that the KGB was infamous for murdering and kidnapping those who spoke out against the state—regardless of their location on the planet. As time went by, the KGB continuously perfected this sinister art with labs like the Kamera.

The “holy grail” for the scientists would have been a poison that was not only tasteless and odorless but also undetectable during an autopsy. The technicians also looked for both slow- and fast-acting toxins that left no clues at an autopsy. They conducted experiments using delivery systems like injections, drinks, and powders and powerful toxins such as curare, digitoxin, ricin, and mustard gas.

Eventually, they had enough poisons to work with and started focusing on delivery methods and the systems to administer the toxins. A good example was one occasion where two Soviet officials were murdered using a type of vapor gun containing a poison that made it appear as though they had both died of heart attacks.

In fact, these official “natural deaths” were never once suspected to be assassinations until years later when a Soviet agent defected and took credit for the crimes. The scientists tested their gruesome creations on political prisoners held in prison camps all over the Soviet Union. If any of these test subjects were not killed by the poisons, they were summarily shot.

It seems as though the fate of the Kamera is unclear. According to a declassified CIA document from 1964, the Soviets abandoned the Kamera in 1953, although it is believed to still exist in some form or another.

7 Jose Delgado

Electronic Control Of The Mind

Streaming hotly over the wooden structures and below into the ring, the bright afternoon Sun lights up fiery eyes as it falls onto a powerful and angry bull staring down his prey. Enraged at being disturbed, the bull charges at the man standing there, seemingly unarmed and looking very vulnerable.

But incredibly, just as the behemoth reaches his defenseless target, the huge animal stops dead in his tracks and just stands there, snorting heavily and looking around nervously. Only then do you see that the “unarmed and defenseless” man was actually a scientist, now looking rather smug, with a radio transmitter in his hand. The scientist had only to press a button to stop a charging bull.

You watch again in silent amazement as the scientist presses another button on the device, and the bull smartly turns and simply trots harmlessly out of the ring. What you do not know was that the day before, the scientist—Dr. Jose Delgado of Yale University—had painlessly implanted a series of fine wire electrodes into predetermined regions of the brain of the animal. The bull was obeying commands caused by electrical stimulation of specific areas of his brain using wireless radio signals tuned to the frequency of the wire electrodes connected to him.

Conducted in the 1960s in Cordoba, Spain, this experiment was one of the most incredible displays of intentional animal behaviorial modification using external control of the brain. The doctor was attempting to discover what makes bulls brave. Just as in his other experiments that concentrated on finding biological reasons for things such as emotions, personality traits, and behaviorial patterns in both animals and man, he succeeded by way of electrical stimulation of the brain.

Simply put, he found that people could be made to act in a variety of ways with just the push of a button. He could cause sudden and acute bouts of passion, euphoria, and anger in patients at will. In one chilling and disturbing experiment, a calm and collective epileptic woman nonchalantly playing her guitar was made, at the push of a button, to suddenly start smashing the instrument against the wall in an instant fit of rage.

Delgado concluded that only an increase or decrease in aggression was possible using this technique and that a specific behavior could not be accurately produced. Controversy over whether his motives were geared more toward mind control or preventive psychology exists, but Delgado maintains that the latter was and has always been the case.

6 Egas Moniz

A Lobotomy Gets Him Shot

Egas Moniz, a Portuguese neurologist in 1936, devised a surgical procedure to treat schizophrenia called a prefrontal leukotomy, or more commonly, a lobotomy. The operation calls for incisions to be made in the brain, destroying connections between the prefrontal lobe and other areas of this vital organ. The exceedingly delicate operation was successfully used globally for treating schizophrenia, earning Moniz the Nobel Prize in 1949. But the accolades didn’t last long.

Introduced in 1952, chlorpromazine was our first neuroleptic drug and the first one discovered to have a positive effect on schizophrenia. The idea of a noninvasive treatment for schizophrenia, such as an oral medication, would and did win over the scientific community soon after it was known to work and medically available. Since 1960, a more aggressive form of lobotomy is sometimes used but only when severe anxieties and uncontrollable syndromes resistant to other forms of therapy are being treated.

Moniz conceded that some personality and behavioral degradation is expected with some lobotomized patients. But he also insisted that the negative cases were overshadowed by a corresponding decrease in the adverse effects of mental illness. Despite this statement, Moniz had at least one disgruntled patient who did not agree with him and proceeded to shoot him as a result, leaving him in a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

5 Ivan Pavlov

His Experiments On Dogs Graduate To Kids

“Pavlovian conditioning,” like most notable advances in science, was accidentally discovered. This time, it was by a Russian physiologist named Ivan Pavlov. During the 1890s, the scientist was investigating salivation (drooling) in dogs in response to food.

Pavlov noticed that whenever he entered the room, even without food for them, the dogs would salivate. By 1902, he was looking at the idea that there are certain things that a dog does not need to learn such as salivating over food. This reflex must be “hardwired” into the animal since they do not learn to salivate whenever they see food. It just happens.

In behaviorist terms, this is called an “unconditioned response.” Pavlov proved the existence of the unconditioned response by giving a dog a bowl of food and then measuring its saliva output. When he discovered that even something only reminding the dog of food still triggered it to drool, he knew he was onto something of scientific value. As a result, he would dedicate his entire career to this line of study.

Pavlov quickly noted that the lab dogs had learned to associate his lab assistant with food. He had to assume this behavior had been learned because there was a time that they did not do this. So a point had arrived when this had changed. Pavlov knew that the dogs in his lab had somehow learned to associate food with his lab assistant. Since changes in behavior are usually the result of learning, the assistant must have started as a neutral stimulus for the dogs, which became a positive one after being unintentionally associated with the unconditioned stimulus of food.

Pavlov used a bell in his experiments as a neutral stimulus. Whenever a dog got food, he would ring the bell. After a dog became conditioned to the procedure, he just rang the bell without giving the dog any food and, as expected, the action caused an increase in salivation.

Since this response had been learned, it was called a “conditioned response” and the neutral stimulus had become a “conditioned stimulus” in the process. With dogs, Pavlov discovered that two stimuli had to be introduced one right after the other for the association to be made. He dubbed this the “law of temporal contiguity.”

In 1920, John B. Watson, a Johns Hopkins professor, was fascinated with Pavlov’s research on conditioned stimulus. Watson wanted to try to create a conditioned response in a human child. The professor found his subject in a nine-month-old child named “Albert B.” (aka “Little Albert”).

To start the experiment, Little Albert was given, among other things, a white rat, a Santa Claus mask, a white rabbit, and a dog. The toddler was not afraid of any of them and seemed to favor the white rat. After Albert became acclimated to the items, a scientist would smack a metal bar, making a loud bang and scaring the child whenever he made a choice.

Soon, due to this conditioning, Little Albert became afraid of the mask and the rat and even a fur coat. What was particularly disturbing about the entire ordeal was that Watson never attempted to undo any of the harm he may have inflicted on his innocent subject.

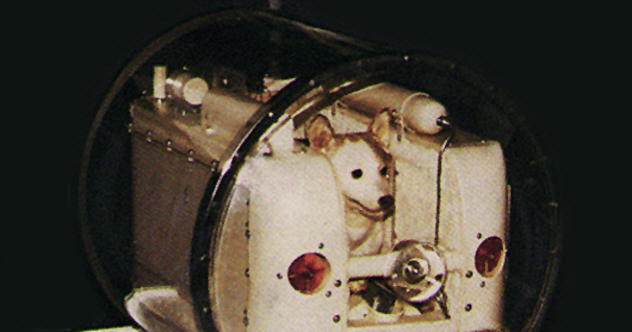

4 The Russians’ First Cosmonaut

On November 3, 1957, the former Soviet Union put their first cosmonaut into space, and it was not Yuri Gagarin. The achievement was touted worldwide as a soaring victory for the Soviet Union, giving them a commanding lead over the US in the race to space. What many do not know, though, is that it was a suicide mission for the lone passenger of the small spacecraft—a dog called Laika.

It was the dawn of spaceflight and just getting there was the battle. Getting back was another story and a problem that would have to wait for future missions. According to the Associated Press, Laika was a stray recovered in Moscow just a week or so before launch. She was promoted to cosmonaut because she was small enough and had a good disposition. In total, the Soviet Union sent up 36 dogs in rockets, and although not the first sent up, Laika was the first to achieve a successful orbit.

The Soviet Union was leading the US in the space race—or at least, it appeared that way. Sputnik I, the first man-made satellite, had been put into orbit just one month earlier. When Sputnik II achieved orbit with Laika aboard, the US fell even further behind. The media could not decide whether to ridicule the event or praise it, which should probably be expected, because the bottom line was simple: Somebody had to send an animal up first, and it was just a question of who that would be.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the end of the Cold War, leaked information from the former Soviet Union began to surface, clearly stating that the animal did not die the “humane” death that was advertised by the Soviets. They had long reported that the dog had died a painless death after a week in orbit. But the Institute of Biological Problems in Moscow leaked the truth in 2002. According to the leak, Laika had become overheated and panicked, causing her death within just a matter of hours after launch.

Personally, the more I think about it, this is a rare case of the truth being better than the lie because a quick demise in just a matter of hours for Laika seems a lot more humane to me than a week floating in space scared, lonely, and slowly dying. If one must go, the quicker the better, right? What do you think?

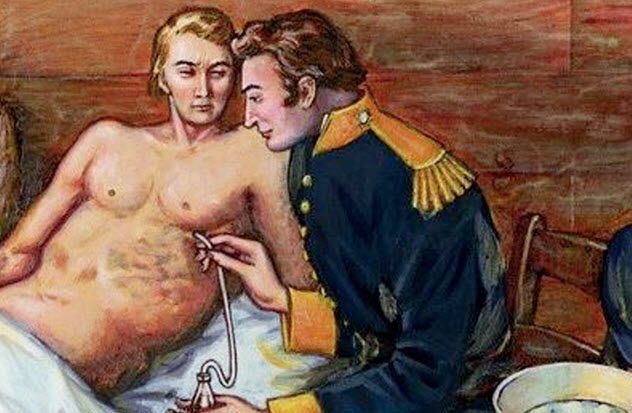

3 Talk About A Stomachache

William Beaumont obtained his medical license in June 1812 from the Medical Society of Vermont. That same month, the War of 1812 erupted and Beaumont joined the US Army with a commission as surgeon’s mate. After a short retirement in 1815, he accepted a commission as a post surgeon in what is now Michigan at Fort Mackinac. On June 6, 1822, an accident occurred that would make Beaumont famous. A 19-year-old French Canadian fur trapper named Alexis St. Martin was accidentally shot in the abdomen with a shotgun at close range.

In spite of a horrible prognosis for someone with a gutshot, St. Martin did recover. But it took 10 months to do it. After almost a year, a hole remained in his abdomen that would not close, producing a passageway directly into his stomach. Seeing an opportunity to do some serious science, Beaumont took St. Martin into his own home to treat him.

The stomach and digestive system were a complete mystery to science 200 years ago. Realizing this, Beaumont saw his chance in May 1825 and started conducting experiments on his young houseguest. For the eight years from 1825 to 1833, Beaumont conducted four sets of experiments on St. Martin while stationed at various posts around the Great Lakes region. This caused gaps in his experiments—and in his notes—lasting from months to years, which was also due to his forays into Canada.

But eventually realizing his limited knowledge of chemistry, Beaumont employed the services of Yale chemistry professor Benjamin Silliman and University of Virginia physiology professor Robley Dunglison. Both scientists analyzed specimens of gastric juice from St. Martin and determined that it consisted of hydrochloric acid, which confirmed the suspicions that Beaumont had formed from his experiments.

Beaumont would dangle pieces of different foodstuffs like meat or eggs into the stomach of his patient, all the while taking detailed notes on how long various foods took to digest. These could not have been very pleasant experiments, to say the least.

2 Domestic Biological Warfare

With operation names like “Drop Kick,” “Big Itch,” and “Big Buzz,” the United States Army Chemical Corps, according to some, let loose mosquitoes infected with yellow fever over Avon Park, Florida, and Savannah, Georgia, back in the 1950s. At the time, the Chemical Corps thought strongly that a surprise attack with some 230,000 infected mosquitoes would be impossible for a nation to react to as well as extremely hard to detect in time to do anything about it.

The corps put its theory to the test in the 1950s by exploring the possibility of weaponizing vermin such as mosquitoes and fleas when they released uninfected mosquitoes over Avon Park, Florida, and Savannah, Georgia. The tests were done just to determine how far the insects would spread once released into the environment.

Many bloggers and watchdog groups have made unproven claims that the military released infected mosquitoes over Savannah and Avon Park, although no outbreaks of yellow fever in those areas have ever been reported. Allegedly, after every mosquito release, army agents would come in acting as health officials to document the results.

Recently declassified documents reveal that these tests were actually conducted but with mosquitoes that were not infected with yellow fever. Reports by an unidentified Avon Park resident refer to an outbreak of dengue fever in the area that allegedly could be traced back to the army experiments and the CIA. There are also other unconfirmed claims that these alleged experiments in biological warfare caused six or seven American deaths.

At the corps’ historical office in Maryland, there is a document called “Summary of Major Events and Problems” which states:

In 1956, the corps released 600,000 uninfected mosquitoes from a plane at Avon Park Bombing Range, Florida. Within a day, the mosquitoes had spread a distance of between [2–3 kilometers (1–2 mi)] and had bitten many people. [ . . . ] In 1958, further tests at Avon Park AFB, Florida, showed that mosquitoes could easily be disseminated from helicopters, would spread more than [2 kilometers (1 mi)] in each direction, and would enter all types of buildings.

Beatrice Peterson, a longtime Avon Park resident, never knew of the mosquito releases, but she did recall the screwworm flies that were released in the mid- to late 1950s. She was 14 and remembered planes dropping boxes, but she could not recall what type of aircraft they were.

In the end, it seems as though the army did drop uninfected mosquitoes. But in my humble view, the action remains a public health hazard that should not be practiced by any government.

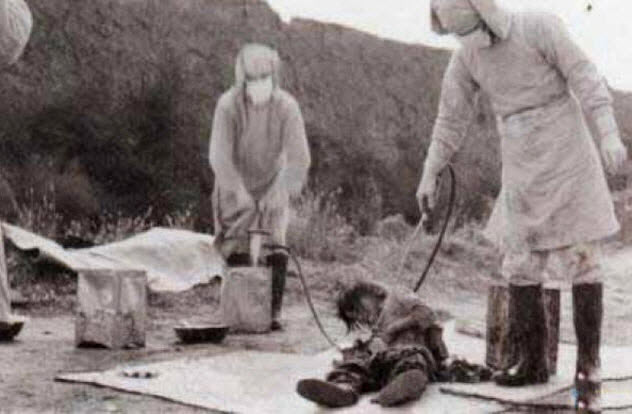

1 The Japanese And Unit 731

During World War II, two biological warfare research facilities were owned and operated by the Japanese Imperial Empire. This was in complete violation of the 1925 Geneva Convention and the resulting ban on chemical and biological warfare.

These research facilities were called Unit 100 and Unit 731 and were commanded by Lieutenant General Ishii Shiro. Under his command, 3,000 Japanese scientists and researchers labored at infecting human subjects with dangerous diseases such as the anthrax virus and the black plague.

Before dying of their respective afflictions, these test subjects were then eviscerated, or surgically gutted, with no anesthesia whatsoever in order to study the effects of these diseases upon human organs. Due to the highly secretive nature of these units, a complete list of their horrific experiments is not available.

Actual testimony from participating surgeons helps to shed some gory light on these gruesome experiments. One medical assistant, who wished to remain anonymous, described his first vivisection in a 1995 interview with The New York Times: “I picked up the scalpel . . . he began screaming. I cut him open from the chest to the stomach, and he screamed terribly.”

Unit 731 did not stop at vivisections since they were known to try out new biological weapons on their subjects, including dirty bombs loaded with plague-infested fleas or deadly cultures. One horrific experiment conducted by the Japanese scientists involved placing subjects dubbed “logs” inside pressure chambers to see how much pressure it took to blow their eyes out of their sockets. Other subjects were forced to stay outside during winter until their limbs were frozen solid so that Japanese doctors could find better ways to treat frostbite.

Unit 731 was also tasked with developing better toxic gases for the Japanese army. “Logs” made perfect subjects for these morbid experiments, too. A graduate student in Tokyo found documentation in a bookstore describing horrendous experiments conducted on humans during the war. The documents speak of the adverse effects of massive dosages of the tetanus vaccine, with tables indicating the time it took victims to die. It also described the bodies’ muscle spasms.

During World War II, the Japanese Imperial Army used biological and chemical weapons developed by Unit 731 to kill or injure at least 300,000 Chinese victims. At least 3,000 Korean, Mongolian, Russian, and Chinese victims also died due to the experiments conducted by Unit 731 in the six years between 1939 and 1945. Not one prisoner came out alive.

Duane lives in northwestern Pennsylvania in the United States of America and in “one of the Original 13” as he likes to say, where he grew up with a fascination for collectibles like baseball cards, coins, stamps, and old bottles, just to name a few. Always a self-starter, he has taught himself many different things and has ended up with a large variety of skills and hobbies in both old and new and has recently started putting them to use on the Internet. He has been writing in several capacities for several decades.