Movies and TV

Movies and TV  Movies and TV

Movies and TV  History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Great Meta Horrors to Watch Before Scream 7

History

History 10 Brave Women Who Fooled Entire Armies

Crime

Crime 10 Criminal Masterminds Brought Down by Ridiculous Mistakes

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Franchises That Started Dark but Turned Surprisingly Soft

History

History 10 Wars That Sound Made Up (but Absolutely Happened)

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Movie Adaptations That Ruined Everything for Some Fans

History

History 10 Dirty Government Secrets Revealed by Declassified Files

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Wacky Conspiracy Theories You Will Need to Sit Down For

Movies and TV

Movies and TV 10 Weird Ways That TV Shows Were Censored

Our World

Our World 10 Places with Geological Features That Shouldn’t Exist

Top 10 Times We Tried Controlling The Rain And Failed

The ability to control rain has fascinated us from time immemorial. While we achieve this today by spraying clouds with chemicals, in the past we used some downright bizarre methods that might or might not have worked. In Kursk, Russia, women threw strangers into rivers or drenched them in water. In Armenia, it was the wife of the local priest that got drenched in water, and in North Africa, religious people were thrown into springs against their will. But throwing people into rivers and springs or drenching them in water are just two of the many ways we have tried controlling rainfall. Here are ten others.

10Hail Cannons

Hail cannons are bizarre-looking contraptions that supposedly stop the formation of hail. They were first proposed by an Italian professor in 1880 and were first built by Austrian M. Albert Stiger between 1895 and 1896. Stiger’s cannon resembled a giant megaphone, and it fired smoke rings that caused an upward moving wind that supposedly prevented hail from forming in the clouds.

Stiger’s hail cannon became a hit after the region he tested it in suffered no hail for two consecutive years. It—along with several other designs—prominently featured on European farms but their reliability was questioned after hail fell in regions they were employed. Whenever this happened, die-hard supporters of the cannons claimed the hail was caused by poor usage and positioning of the cannon.

To clear the air on whether or not hail cannons worked, the Italian government tested over two hundred cannons at different locations over a two-year period. The test locations suffered severe hail during the tests, and the hail cannon was termed a failure. Nevertheless, some farmers stuck to them and they are still used on some farms today. Rather than firing smoke, they fire a mixture of oxygen and acetylene gas, which, like smoke, supposedly disrupt hail formation. While their reliability remains in doubt, there is no doubt over their loudness, which makes neighbors consider them a nuisance.

9Moisture Accelerator

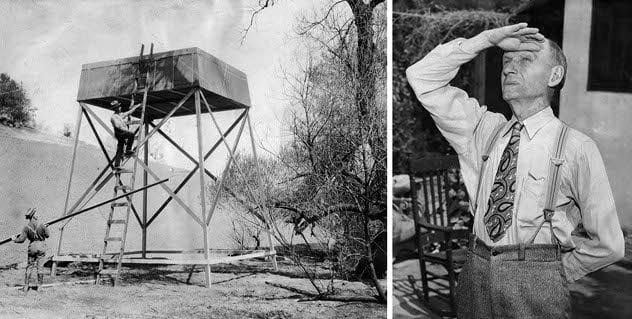

The moisture accelerator was an invention of rainmaker, Charles Mallory Hatfield. It was a mixture of twenty-three secret chemicals that Hatfield set on fire to attract rain-producing clouds. Hatfield got his break in December 1904, when he promised some Los Angeles businessmen eighteen inches (45 cm) of rain in five months for a thousand dollars. They took the deal, and he delivered as promised. This earned him instant fame and his service was widely sought after. He never disappointed and charged up to $4,000 for rainfall.

In December 1915, he extended his services to San Diego—which was facing a terrible drought—where he promised rainfall that would overfill the Lower Otay reservoir dam, in exchange for a payment of $10,000. San Diego took the deal, and Hatfield got down to work. First, he constructed a 20-foot (6 m) tower on which he set his moisture accelerator on fire. The city experienced light showers for a few weeks until January 15, 1916, when it began raining heavily.

The rain lasted for five days during which the San Diego river overflowed its bank, mountainous regions experienced landslides, and heavy flooding washed away houses, roads, rail, and telephone lines. Despite the catastrophe, Hatfield called the city and promised heavier rains. The rain got heavier, as he promised, and the Lower Otay reservoir dam overfilled and broke, sending forty feet (12 m) of water into the city.

By the time the disastrous rain, which was dubbed “Hatfield Flood,” was over, the town had experienced almost thirty inches (76 cm) of rainfall, large-scale destruction, and fifty deaths. Meanwhile, Hatfield calmly walked into the city to demand his pay. The city was already facing several lawsuits over the rain and only agreed to pay him on the condition he accepted responsibility for the damages. Hatfield never accepted responsibility and was never paid.

8The Storm King’s Massive Bush Fire

Prior to the nineteenth century—and for much of it—people believed rain could be caused and stopped by noise. This was why bell-ringers rang church bells before storms. People also believed there was some relationship between rainfall, cannons, and guns, as rain had been observed to fall after great battles.

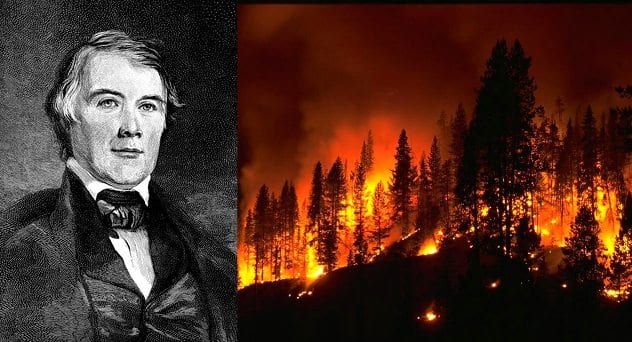

James Pollard Espy (aka the “Storm King”), the first official weather forecaster of the United States, belonged to this school of thought. However, he believed rainfall was not caused by the battles themselves, but by the warmth released from the weapons used during these battles. So, he proposed that heat and fire could cause rain.

To experiment his theory, he wrote to the US Congress and requested for a 600-mile (966 km) stretch of forest that extended from the Great Lakes at the border with Canada down to the Gulf of Mexico. His plan was to set the forest on fire to see if it would produce rain. The US Congress refused his requests over fears the wildfires could spiral out of control, and the rains might not come to put them out. Also, they did not want Espy or the government to have power over the rain.

7The Battle of Dryhenceforth

Edward Powers was another person who linked rainfall with war. Specifically, he believed rainfall was caused by artillery used in battle. Like Espy, he requested that the US Congress provide funds to experiment his theory. Unlike Espy, Congress accepted his request and, in 1891, sent General R.G. Dyrenforth (who was actually not a general) to oversee the experiment in Texas.

Dyrenforth arrived in Texas with several men and cargoes of explosives, gunpowder, cannons, balloons, and kites. At the front of the “battle line” in his war against the skies were sixty mortars, all aimed at the sky. Close to the mortars were dynamites that were affixed to the ground, and behind the mortars were large kites and 10-20 foot (3-6 m) tall balloons that would be used to deliver explosives into the skies.

Even with his large cache of explosives and artillery, Dyrenforth’s assault against the skies was a total failure. According to unimpressed reporters on the ground, the men manning the explosives looked confused, and the bombs were fond of detonating in the wrong places. Dyrensforth’s only achievement included destroying a tree, window, and starting random fires. There was no rain, and angry Texas citizens renamed him “Dryhenceforth.”

6Cloudbusters

The cloudbuster was a supposed rainmaking and rain-destroying machine invented by Austrian psychiatrist William Reich. According to him, the machine created or destroyed rain by exploiting the “Orgone Energy” that supposedly holds the elements of a cloud together. Whether the machine worked remains a mystery, but in 1953, Maine farmers paid Reich to make rain, which fell the day after Reich operated his machine.

Reich had specific rules for operating the cloudbuster, as improper operation supposedly led to flood, tornadoes, forest fires, and death of the operator. Firstly, the operator should never try to impress anyone when operating the machine. He should also cover his hands with insulating gloves and ensure there was no electrical or radioactive equipment nearby. The cloudbuster should also be parked in moving water that covered all its metal parts.

5Operation Popeye

Operation Popeye was a top secret cloud seeding operation executed by the United States during the Vietnam war. It was intended to overwhelm North Vietnam and Laos with excess rainfall that would turn their roads into marshes and hinder North Vietnamese supplies going into South Vietnam via Laos. It was launched in 1967, although, experimental operations that caused rain in 82 percent of the seeded clouds had begun a year earlier.

The operation was supposed to be top secret for several reasons including the fact that other countries might blame the United States for similar unfavorable weather conditions. However, if the plan leaked, the US was expected to tag the operation as a humanitarian operation. The plan leaked, as expected, and the operation was canceled in 1972.

However, top defense officials including the defense secretary, Melvin R. Laird, initially denied its existence and only admitted it happened two years later. Then, defense officials claimed it was a success as it increased rain by 30 percent and slowed down North Vietnam’s movement, especially through the infamous Ho Chi Minh trail.

4The Fraudulent Rain King

Frank Melbourne was an Australian rainmaker known as the “Rain King” or the “Rain Wizard.” His methods looked similar to Hatfield’s, and he claimed he could cause rainfall by mixing and burning some secret chemicals that produced rainmaking clouds.

Melbourne always locked himself in a house, railroad car, or barn when burning his chemicals, and the smoke only rose into the skies through its openings. His rainmaking activities became a source of income for his brother who placed bets against people who claimed Melbourne could not produce rain.

Melbourne went out of business when the public realized he was not a rainmaker but a fraud, who targeted his services at towns where rainfall had already been forecast.

3Rain Dance

Rain dances are elaborate ceremonies that Native American tribes use to summon rains during droughts. It was (and is still) common among Southwestern Native American tribes like the Mojave, Pueblos, Navajos, and Hopi, who are more susceptible to drought.

Dancers dress in elaborate and colorful costumes, complete with artifacts that symbolize natural conditions. For instance, male dancers add feathers to their masks to represent the wind, and turquoise to their clothing to represent the rain. When dancing, males and females maintain separate lines, four feet apart, and take mastered steps and movements in unison. Drums are not used, and dancers depend on the sound of their synchronized steps to make up for it.

2Rain Battles

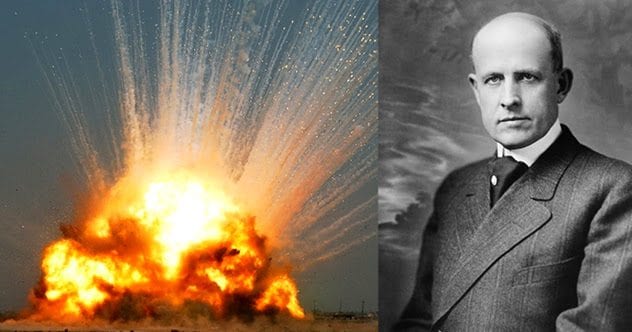

Charles William Post was another follower of the rainfall-war theory. Like Edward Powers, he believed artillery caused rains, and he tested his theory in a series of self-sponsored experiments remembered today as the “rain battles.” In 1910, he launched the first of his thirteen rain battles in Garza County, Texas, when he released a kite fitted with dynamite into the skies.

The kite exploded as expected, but Post thought it was too dangerous, so, he switched to arranging dynamites—in fourteen-pound (6 kg) stacks—on highlands, and detonating them at ten-minute intervals. During another battle, he expended 24,000 pounds (11,000 kg) of dynamite, which reportedly started a rain. Post spent over $50,000 on his rain battles, and according to him, seven of his attempts caused rainfall. However, observers noted that the experiments were held during the rainy season when rain was already expected.

1Rain Stones

Rain stones have been used in elaborate rainmaking rituals in Africa, North America, Britain, Japan, Australia, and Ancient Rome since at least A.D. 1600. And for all we know, they might still be in use today. They were used to either summon the rains or communicate with a supposed god of rain.

In Australia, the stone was placed on a heap of sand, and the rainmaker danced around it while singing or reciting incantations. In Ancient Rome, the stone was called “lapis manalis,” which means “pouring stone.” It was kept in the Temple of Mars, from where it was taken to the Temple of Jupiter (the Roman god of Storms) inside the city whenever rain was needed. The labis manalis is believed to have had a hollowed middle that was filled with water that trickled over its top and down its sides to resemble rain.

Oliver Taylor is a freelance writer and bathroom musician. You can reach him at [email protected]