Mysteries

Mysteries  Mysteries

Mysteries  History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Mysteries

Mysteries Top 10 Haunting Facts About the Ghost Ship MV Alta

History

History 10 Surprising Stories About the Texas Rangers

Humans

Humans 10 Philosophers Who Were Driven Mad by Their Own Theories

Who's Behind Listverse?

Jamie Frater

Head Editor

Jamie founded Listverse due to an insatiable desire to share fascinating, obscure, and bizarre facts. He has been a guest speaker on numerous national radio and television stations and is a five time published author.

More About Us Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous 10 Video-Game-Worthy Weapons and Armors from History

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Psychics Who Accurately Predicted Wartime Events

The Arts

The Arts 10 Pieces of Art Inspired by a Broken Heart

Health

Health 10 Science Fiction-Sounding New Medical Treatments

History

History 10 Surprising Facts About the Father of Submarine Warfare

Space

Space Ten Astonishing New Insights into Alien Worlds

Weird Stuff

Weird Stuff 10 Bizarre Summer Solstice Rituals Still Practiced Today

Top 10 Terrifying Ways To Go Blind

When I was 23, I started losing my eyesight, and the doctors didn’t know why.

It began innocently enough, with a less-than-perfect chart reading during a routine eye exam. Before long, I was referred from optometrists to ophthalmologists to neuro-ophthalmologists… and no one had a definitive diagnosis. When you’re stumping doctors whose titles have seven syllables, there’s a problem.

The ordeal lasted nearly two years, during which time my vision slowly deteriorated. Today, at age 41, it stands at 20/70 corrected. It isn’t pretty but, as the following list shows, things could be a hell of a lot worse.

10 Brain Tumor

“Mass lesion.”

The scariest two words I’ve ever read were scrawled on a medical pad. I’d stolen a glance while the optometrist was in the other room – possibly, I catastrophized, planning my funeral. I was rattled because the eye test I’d just taken clearly hadn’t gone well; confirming this, underneath the doctor’s horrifying headline were the results of my visual field examination,[1] which showed gaping scotomas, or blind spots, in both eyes.

The scotomas were mostly symmetrical; the left eye’s major defects were in the upper left-hand quadrant, while the right eye was mostly impacted on the upper right. The optometrist’s suspicion, I learned later, was that a brain tumor was pressing on my optic chiasm[2] – a spot at the base of the brain where our optic nerves cross. A lesion causing pressure at the intersection could explain the sort of bilateral visual field damage I was exhibiting.

The visual field examination was ordered after it became evident that I was unable to read the 20/20 line with my corrected prescription eyeglasses; that might be typical for an older person… but I was 23.

Obviously, the optometrist couldn’t know this for sure, so “mass lesion” was not a diagnosis but rather a referral. The optometrist was ordering an MRI of my brain to determine whether a tumor was the eyesight-robbing culprit. After… the… longest… four days… of… my life… the results finally came back…

…clean. No tumor. I wasn’t dying, but we still didn’t have an answer for the vision loss. The remainder of this list are diseases I could have had, and one that I do.

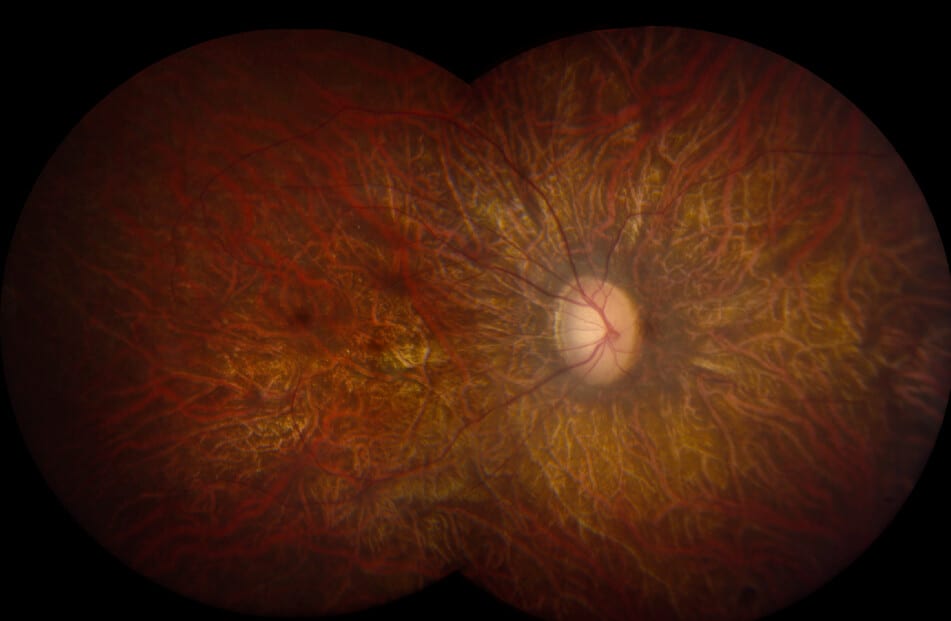

9 Retinitis Pigmentosa

Commonly shortened to RP, retinitis pigmentosa[3] is about as scary as it sounds. Basically, your field of vision slowly narrows, starting with peripheral blindness that leads to a sort of tunnel vision. That tunnel then slowly collapses, which can eventually result in total blindness.

The disease is so named because it involves a breakdown and loss of cells in the retina — the light-sensitive tissue lining the back of the eye. The disorder results from adverse changes in any one of more than 50 genes necessary for healthy development of retinal photoreceptors – also known as rods and cones[4] for their distinctive shapes. RP is rare, but not TOO rare; it affects an estimated 1 in 4,000 people. Considering my visual field test, those odds no longer seemed long.

In RP’s early stages, sufferers typically experience night blindness and a gradual loss of the visual field. Rates of progression vary by individual, but the majority of folks with RP eventually lose most of their eyesight, often so severely that they have difficulty performing essential tasks such as reading, driving, walking without assistance, or recognizing faces and objects. Fun!

One of the tools used to diagnose RP is an electroretinogram,[5] or ERG, which measures electrical sensitivity in photoreceptors. Less reaction would mean less cells – a sign of RP. My reactions were normal, ruling it out.

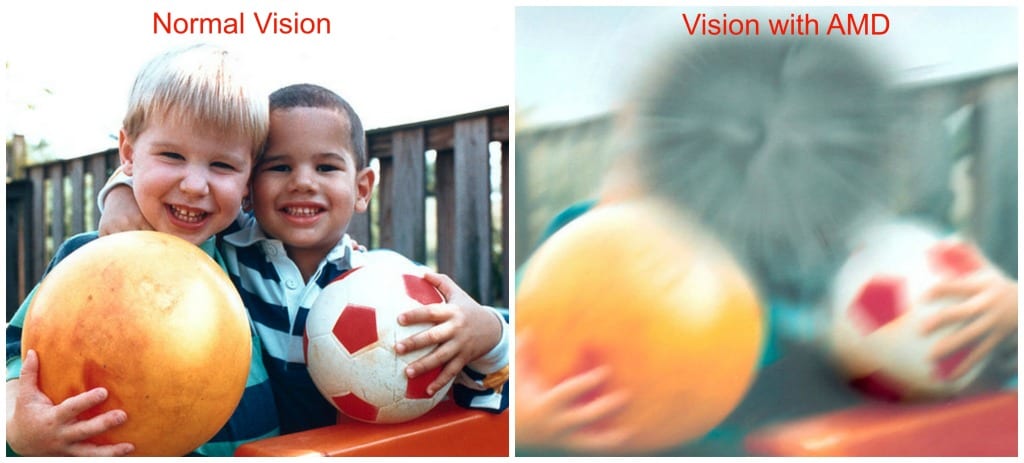

8 Macular Degeneration

Macular Degeneration[6] is the leading cause of vision loss, affecting more than 10 million in the U.S. alone – more than cataracts and glaucoma combined. And unlike cataracts (which can be cured) or glaucoma (which can be significantly mitigated via treatment), Macular Degeneration is both incurable and largely unstoppable.

Macular Degeneration entails the deterioration of the central retina, called the macula. The macula is responsible for central vision, which naturally requires more detail. We use our macula to read, drive, distinguish colors and recognize faces.

Prognoses for MD vary broadly, as it can pause with seemingly no explanation. Mild cases my experience no clinically perceivable vision loss; if the disease progresses, people experience wavy or blurred vision. If it continues to worsen, however, central vision can be completely lost, leaving sufferers with only peripheral vision – basically the exact opposite of tunnel vision.

There are two basic types of Macular Degeneration: “dry”[7] and “wet”[8]. Dry MD, which comprises 85-90% of cases, does not involve any leakage of blood or serum, but rather the accumulation of yellow deposits called drusen under the macula. Dry MD generally has a better long-term prognosis, with most retaining decent (approximately 20/40) central vision.

With Wet Macular Degeneration, abnormal blood vessels grow under the macula. Their leakage causes a bulging that can lead to rapid, severe vision loss.

MD is usually age-related, meaning it starts later in life. A less common form of MD, Stargardt disease,[9] is found in young people, and has a particularly poor prognosis for long-term vision retention. Fortunately, this wasn’t my diagnosis, either; my macula were healthy.

7 River Blindness

When you present with unidentifiable vision loss, doctors ask seemingly arcane questions in an attempt to rule out some of the outliers. One of them is “Have you been to Africa or the tropics lately?”

More commonly known as River Blindness, Onchocerciasis[10] is an eye and skin disease caused by tiny worms, which are transmitted through the bite of a type of blackfly. The insects tend to breed in fast-flowing streams and rivers, hence its informal moniker. Once inside the body, the worm produces thousands of baby or larval worms, called microfilariae, which migrate into the skin and eye. How adorably debilitating.

When the microfilariae die, they emit a highly toxic compound that causes insatiable itching and eye lesions that, over time, can lead to irreversible blindness and disfiguring skin diseases. Alarmingly, in some West African communities about 50% of men over 40 years of age were once blinded by Onchocerciasis.

I had not been to Africa, Latin America or other known trouble spots. it was determined that I had not been blinded by the bite. Next question, doc.

6 Lead Poisoning

“Have you come into contact with any old pipes, or paint, or drank water that wasn’t fresh?”

There’s no polite way to basically ask someone if they’ve been eating paint chips.

The doctors did, however, have to rule the scenario out. In addition to affecting brain function, lead poisoning[11] can have devastating effects elsewhere in the nervous system – including the optic nerve, which transmit images to the brain for processing.

Through this cognitive dysfunction, lead poisoning can present with a variety of visual symptoms, including difficulty seeing in low light, blurriness, and chronic eye irritation. It also brings an increased risk of developing cataracts, though that wasn’t a factor for someone in his early 20s, as I was.

As evidenced by the recent lead catastrophe in Flint, Michigan,[12] lead poisoning is still far too common for something so preventable. Lead has historically been used in a variety of consumer products including gasoline, paint, craft supplies, and plumbing materials – hence the doctor’s off-putting question about contact with pipes. Fortunately wide-scale lead exposure in developed nations is rare.

Top 10 Unbelievable Types Of Illusions And Hallucinations

5 Nonarteritic Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

… is a terrifyingly intricate way to say “ocular stroke.”

An ocular stroke occurs when the optic nerve experiences a marked, sudden reduction in blood flow and, therefore, oxygen. It can be part of a larger stroke that affects other areas of the body, or a standalone event limited to visual sensitivity.

Like traditional strokes, ocular strokes vary greatly in severity. The condition affects approximately one in 10,000, including a prominent New York Times opinion writer named Frank Bruni. In February 2018, Bruni published a poignant piece strikingly titled “Am I Going Blind?”[13]

The entry’s introduction eloquently showcases the mortifying, unheralded alarm the disorder evokes: “They say that death comes like a thief in the night,” he writes. “Lesser vandals have the same M.O. The affliction that stole my vision, or at least a big chunk of it, did so as I slept. I went to bed seeing the world one way. I woke up seeing it another.”

Bruni describes the vision loss as “a thick, dappled fog” affecting the right half of his visual field, which caused not only extreme blurriness but a sort of off-kilter feeling that left him “felling drunk without being drunk.”

Ocular stroke victims live not only with vision loss but also a lifelong sense of foreboding, because having one significantly raises the likelihood of suffering another. Bruni reported that, over the next five years, he faced a 20% chance of a similar event in his remaining good eye. In other words, he has a one in five chance of becoming functionally blind.

The pattern of my vision loss, however, did not suggest a stroke. While it remained a “maybe” on the diagnosis docket, doctors kept searching for a likelier suspect.

4 Devic’s Disease

One of the disorders that most closely mirrored my visual symptoms was, unsettlingly, among the most frightening prospects.

Also known as neuromyelitis optica, Devic’s Disease[14] can be fairly described as multiple sclerosis on steroids. Visually, while MS tends to attack only one eye[15] with optic neuritis (episodic flare-ups attacking the optic nerve), Devic’s Disease typically presents with substantial scotomas (blind spots) in both eyes.

My vision loss was bilateral (both eyes), and a neuro-ophthalmologist confirmed my optic nerves were thinner than normal. In layman’s terms, the cameras (my eyes) were fine but the cables were frayed, significantly blurring the feed.

Devic’s is, simply, brutal. Like its cousin, MS, it is characterized by immune attacks on the optic nerves and the spinal cord. Unlike MS, Devic’s tends to rob large chunks of both vision and mobility without warning – a relapse/remit pattern that mimics MS but with more debilitating episodes. Depending on what sections of the optic nerve and spinal cord are affected, symptoms can include blindness in one or both eyes, weakness or paralysis in the legs or arms, painful spasms, loss of sensation, uncontrollable vomiting and bladder or bowel dysfunction.

An MRI of my spine came back… inconclusive. Unfortunately, the next step was infinitely more painful: a spinal tap.

The fluid was normal. No MS or Devic’s… not yet anyway. The search continued.

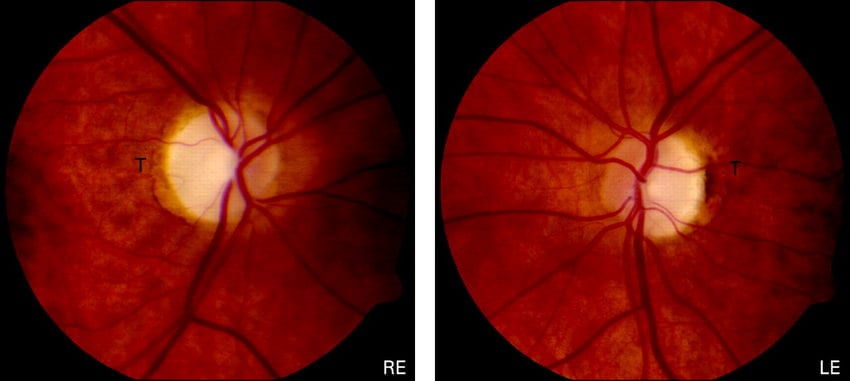

3 Coloboma of the Eye

Derived from a Greek word meaning “curtailed,” colobomas[16] comprise a set of conditions in which normal tissue in or around the eye is missing from birth. This can include incomplete formation of the macula, lens, uvea,[17] optic nerve or, oddly, the eyelids. Visual impairment can run the gamut from virtually asymptomatic to virtually blind.

If confirmed, mine would a moderate case of the optic nerve variety, which involves an abnormal optic passageway that is somewhat “excavated” or hollowed out. Though it is present from birth, it’s not uncommon for mild or moderate cases to go unnoticed until adolescence or early adulthood because, as a doctor explained to me, “you can only see the world through your eyes.” My poor eyesight was normal to me; it took flunking some eye exams to show me it was demonstrably worse than average.

On its face, the notion of a birth defect made some sense, as my mother suffered from preeclampsia – a condition that can cause dangerously high blood pressure – while carrying me. (In fact, three years later, during her second pregnancy, she died from it.) Preeclampsia can choke off oxygen to fetuses, resulting in birth defects.

However, more commonly colobomas are genetic, and there wasn’t evidence of them running in my family. With no formal diagnostic test, another disease was added to the “maybe” column. It was a good maybe, because colobomas typically don’t worsen.

2 Leber’s Syndrome

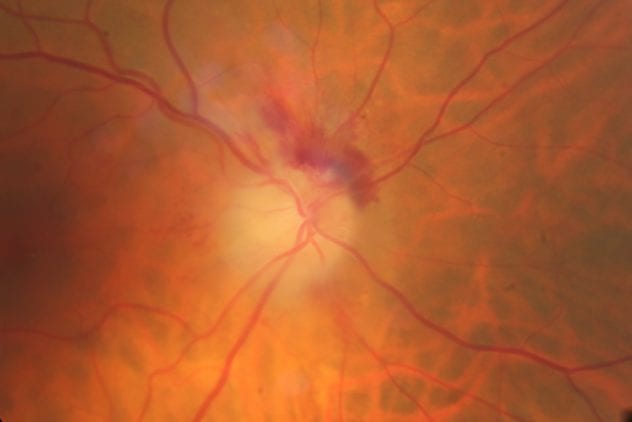

Officially called Leber Hereditary Optic Neuropathy,[18] Leber’s Syndrome is a mitochondrially inherited degeneration of retinal ganglion cells and their axons – long threadlike nerve cells extending to the optic nerve. While it typically affects young men, LHON is inherited maternally, since we get out mitochondria solely from our mothers’ eggs in the womb.

Leber’s usually presents with acute onset of visual loss, first in one eye, then the other a few weeks later; however, in 25% of cases the vision loss can occur in both eyes simultaneously. The disorder then devolves to severe optic atrophy and a permanent decrease of visual acuity.

In the acute stage, affected eyes demonstrate a fluid-filled appearance of the nerve fiber and enlarged or otherwise damaged peripapillary vessels. A pupillary defect also can occur, as the eyes struggle to capture more light.

In addition to bilateral acuity, I had two other symptoms that alarmingly aligned with Leber’s: impaired color vision and the specific locations of my scotomas (blind spots). Mine were cecocentral, meaning they originated from the natural small blind spots we all have (the point where the optic nerve connects with the eye) and enlarged exponentially over time.

Had I had Leber’s I’d likely be nearly blind by now. Luckily, I did not.

1 Dominant Optic Atrophy

After almost two years of uncertainty, the doctors arrived at a sort of diagnosis by process of elimination: Dominant Optic Atrophy.[19]

Also known by its unsettling acronym, DOA, Dominant Optic Atrophy is a rather loosely defined condition characterized by degeneration of the optic nerves. The term “dominant” alludes to its hereditary nature – a clue to doctors because my father has had mild cases of optic neuritis (inflammation).

DOA typically starts during the first decade of life, with affected people frequently developing moderate visual loss and color vision defects. Its severity varies widely – a common issue with eye disorders that also makes them more difficult to pinpoint – with visual acuity ranging from near-normal to legal blindness (which is 20/200–corrected).[20]

Dominant Optic Atrophy remains a bit of a medical mystery: it can be caused by a mutation in any of several genes, some of which have not been identified. Like most eye diseases, there is currently no way to prevent or cure it.

Unfortunately, DOA also has a “Sword of Damocles”[21] aspect to it, meaning it can pause and restart without warning. Luckily, it’s been more than 15 years since I’ve suffered any demonstrable vision loss. However, the prospect of losing more of my precious eyesight will, like my diseased optic nerves, be in my head for the rest of my life.

Another 10 Amazing Optical Illusions

About The Author: Christopher Dale (@ChrisDaleWriter) writes on politics, society and sobriety issues. His work has appeared in Daily Beast, NY Daily News, NY Post and Parents.com, among other outlets.